Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Luigi Galvani

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

Luigi Galvani (/ɡælˈvɑːni/ gal-VAH-nee, US also /ɡɑːl-/ gahl-,[1][2][3][4] Italian: [luˈiːdʒi ɡalˈvaːni]; Latin: Aloysius Galvanus; 9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, physicist, biologist and philosopher who studied animal electricity. In 1780, using a frog, he discovered that the muscles of dead frogs' legs twitched when struck by an electrical spark.[5]: 67–71 This was an early study of bioelectricity, following experiments by John Walsh and Hugh Williamson.

Key Information

Early life and career

[edit]Luigi Galvani was born to goldsmith Domenico Galvani and Barbara Caterina Foschi, in Bologna, then part of the Papal States.[6] A portion of his childhood home still stands in the Giardino Salvatore Pincherle.[7][8]

In 1759, Galvani graduated with a degree in medicine and philosophy and began to practice medicine at nearby hospitals.[6] He published his first work, a paper on the anatomy and physiology of bones, in 1762, when he was 25 years old. Galvani presented the work at the Archiginnasio di Bologna, which allowed him to start lecturing at the Academy of Sciences of the Institue of Bologna (now part of the University of Bologna) where he taught anatomy for most of his career.[6]

In 1766, Galvani was appointed curator of the anatomical museum by the senate of Bologna. This position "required him to give lectures and demonstrations of anatomical operations before surgeons, painters and sculptors."[6] In 1782, he was appointed Professor of Obstetric Arts, which he remained for the next 16 years.

Animal electricity

[edit]Galvani then began taking an interest in the field of "medical electricity". This field emerged in the middle of the 18th century, following electrical researches and the discovery of the effects of electricity on the human body by scientists including Bertrand Bajon and Ramón María Termeyer in the 1760s,[9] and by John Walsh[10][11] and Hugh Williamson in the 1770s.[12][13] The publication in 1791 of Galvani’s main work (De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius), summarizing and discussing more than 10 years of research on the effect of electricity on animal preparations, had an enormous impact on the scientific community and sparked heated controversy in Europe.[14]

-

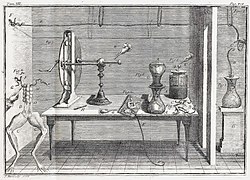

Experiment De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari.

-

Late 1780s diagram of Galvani's experiment on frog legs.

-

Electrodes touch a frog, and the legs twitch into the upward position.[15] (see also: Frog galvanoscope)

Galvani vs. Volta

[edit]Alessandro Volta, a professor of experimental physics in the University of Pavia, was among the first scientists who repeated and checked Galvani’s experiments. At first, he embraced animal electricity. However, he started to doubt that the conductions were caused by specific electricity intrinsic to the animal's legs or other body parts. Volta believed that the contractions depended on the metal cable Galvani used to connect the nerves and muscles in his experiments.[13]

Every cell has a cell potential; biological electricity has the same chemical underpinnings as the current between electrochemical cells, and thus can be duplicated outside the body. Volta's intuition was correct. Volta, essentially, objected to Galvani’s conclusions about "animal electric fluid", but the two scientists disagreed respectfully and Volta coined the term "Galvanism" for a direct current of electricity produced by chemical action.[16]

Since Galvani was reluctant to intervene in the controversy with Volta, he trusted his nephew, Giovanni Aldini, to act as the main defender of the theory of animal electricity.[13]

Personal life

[edit]

Galvani married scientist Lucia Galeazzi, daughter of his mentor Domenico Gusmano Galeazzi, in 1762.[6] After her death in 1790, Galvani moved in with his brother, who was living in their childhood home in Bologna.

Galvani was described by contemporaries as an "honest, mild, modest man, polite, charitable to the unfortunate and always a noble and generous friend."[6] He was noted for his religious devotion and saw his medical work as being a spiritual mission. French dermatologist Jean-Louis-Marc Alibert said of Galvani that he never ended his lessons “without exhorting his hearers and leading them back to the idea of that eternal Providence, which develops, conserves, and circulates life among so many diverse beings.”[17]

Death and legacy

[edit]Galvani actively investigated animal electricity until the end of his life. In April 1798, the Cisalpine Republic, a French client state founded after the French occupation of Northern Italy, required every university professor to swear loyalty to the new authority. Galvani disagreed with the oath and refused to take it; as a result, he was stripped of his offices and sent into poverty. Aldini led a movement to restore him to his university position — it was successful, but his restoration was only announced shortly before his death. Galvani died in his brother’s house on 4 December 1798.[13]

Galvani's report of his investigations were mentioned specifically by Mary Shelley as part of the summer reading list leading up to an ad hoc ghost story contest on a rainy day in Switzerland — and the resultant novel Frankenstein — and its reanimated construct. In Frankenstein, Victor studies the principles of galvanism but it is not mentioned in reference to the creation of the Monster.

Galvani's name also survives in everyday language as the verb 'galvanize' as well as in more specialized terms: Galvani potential, galvanic anode, galvanic bath, galvanic cell, galvanic corrosion, galvanic couple, galvanic current, galvanic isolation, galvanic series, galvanic skin response, galvanism, galvanization, hot-dip galvanization, galvanometer, Galvalume, and psycho-galvanic reflex.

Works

[edit]- De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari commentarius (in Latin), 1791. The Institute of Sciences, Bologna.

- De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari (in Latin). Modena: Società tipografica. 1792.

- Memorie sulla elettricità animale (in Italian). Bologna: Clemente Maria Sassi. 1797.

- [Opere] (in Italian). Bologna: Emidio Dall'Olmo. 1841.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Galvani". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Galvani". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Galvani, Luigi" (US) and "Galvani, Luigi". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26.

- ^ "Galvani". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Whittaker, E. T. (1951), A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity. Vol 1, Nelson, London

- ^ a b c d e f Galvani, Luigi; Pupilli, Giulio C. (1953). Commentary On The Effect Of Electricity On Muscular Motion. Universal Digital Library. Elizabeth Licht. pp. ix–xx.

- ^ Vietto, Sonja (2022-11-24). "Bologna, nuova vita al giardino Pincherle". Bologna24ore.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2025-09-04.

- ^ "La casa di Galvani diventa succursale di una banca". bibliotecasalaborsa.it (in Italian). 2019-11-07. Retrieved 2025-09-04.

- ^ de Asúa, Miguel (9 April 2008). "The Experiments of Ramón M. Termeyer SJ on the Electric Eel in the River Plate Region (c. 1760) and other Early Accounts of Electrophorus electricus". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 17 (2): 160–174. doi:10.1080/09647040601070325. PMID 18421634.

- ^ Edwards, Paul (10 November 2021). "A Correction to the Record of Early Electrophysiology Research on the 250th Anniversary of a Historic Expedition to Île de Ré". HAL open-access archive. hal-03423498. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Alexander, Mauro (1969). "The role of the voltaic pile in the Galvani-Volta controversy concerning animal vs. metallic electricity". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. XXIV (2): 140–150. doi:10.1093/jhmas/xxiv.2.140. PMID 4895861.

- ^ VanderVeer, Joseph B. (6 July 2011). "Hugh Williamson: Physician, Patriot, and Founding Father". Journal of the American Medical Association. 306 (1). doi:10.1001/jama.2011.933.

- ^ a b c d Bresadola, Marco (15 July 1998). "Medicine and science in the life of Luigi Galvani". Brain Research Bulletin. 46 (5): 367–380. doi:10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00023-9. PMID 9739000. S2CID 13035403.

- ^ Piccolino 1998, p. 381.

- ^ David Ames Wells, The science of common things: a familiar explanation of the first, 323 pages ( page 290)

- ^ Luigi Galvani – IEEE Global History Network.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Luigi Galvani". Retrieved 1 September 2014.

Sources

[edit]- Heilbron, John L., ed. (2003). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199743766.

- Piccolino, Marco (1998). "Animal electricity and the birth of electrophysiology: The legacy of Luigi Galvani". Brain Research Bulletin. 46 (5): 381–407. doi:10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00026-4. PMID 9739001.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of galvanize at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of galvanize at Wiktionary- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, Theodore M. (1972). "Galvani, Luigi". In Charles Coulston Gillispie (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 5. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 267–9. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- Farinella, Calogero (1998). "GALVANI, Luigi". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 51: Gabbiani–Gamba. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-88-12-00032-6.

- Bresadola, Marco (2013). "Galvani, Luigi". Il Contributo italiano alla storia del Pensiero: Scienze. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- Piccolino, Marco; Bresadola, Marco (2013). Shocking Frogs: Galvani, Volta, and the Electric Origins of Neuroscience. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199782215. Retrieved 16 July 2025.

Luigi Galvani

View on GrokipediaLuigi Galvani (9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, anatomist, and physiologist based in Bologna, renowned for pioneering the study of bioelectricity through experiments on frog preparations that demonstrated electricity's role in eliciting muscle contractions.[1][2] His observations, beginning in the late 1780s, revealed that static electrical discharges or metallic contacts could trigger convulsions in excised frog legs, leading him to propose the existence of an intrinsic "animal electricity" generated within living tissues, particularly along nerves, to stimulate muscular motion.[3][4] This theory, detailed in his 1791 treatise De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari commentarius, challenged prevailing views and sparked a scientific controversy with Alessandro Volta, who attributed the effects to contact electricity between dissimilar metals rather than inherent biological forces, ultimately contributing to the invention of the voltaic pile.[5][6] Galvani's empirical demonstrations laid foundational principles for electrophysiology, influencing subsequent research into nerve impulses, bioelectromagnetism, and the electrochemical basis of life processes, while his reluctance to engage publicly in the debate reflected his focus on anatomical and physiological inquiry over theoretical dispute.[7][8]

![Electrodes touch a frog, and the legs twitch into the upward position.[15] (see also: Frog galvanoscope)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c7/Galvani-frogs-legs-electricity.jpg/250px-Galvani-frogs-legs-electricity.jpg)