Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Internal bleeding

View on Wikipedia| Internal bleeding | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Internal hemorrhage |

| |

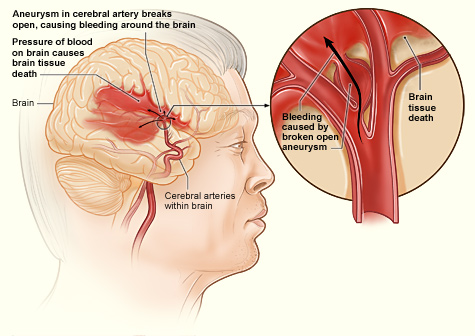

| Internal bleeding in the brain | |

| Specialty | Vascular surgery, hematology, emergency medicine |

| Complications | Hemorrhagic shock, exsanguination |

Internal bleeding (also called internal haemorrhage) is a loss of blood from a blood vessel that collects inside the body, and is not usually visible from the outside.[1] It can be a serious medical emergency but the extent of severity depends on bleeding rate and location of the bleeding (e.g. head, torso, extremities). Severe internal bleeding into the chest, abdomen, pelvis, or thighs can cause hemorrhagic shock or death if proper medical treatment is not received quickly.[2] Internal bleeding is a medical emergency and should be treated immediately by medical professionals.[2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Signs and symptoms of internal bleeding may vary based on location, presence of injury or trauma, and severity of bleeding. Common symptoms of blood loss may include:

- Lightheadedness

- Fatigue

- Urinating less than usual

- Confusion

- Fast heart rate

- Pale and/or cold skin

- Thirst

- Generalized weakness

Visible signs of internal bleeding include:

- Blood in the urine

- Dark black stools

- Bright red stools

- Bloody noses

- Bruising

- Throwing up blood

Of note, it is possible to have internal bleeding without any of the above symptoms, and pain may or may not be present.[3]

A patient may lose more than 30% of their blood volume before there are changes in their vital signs or level of consciousness.[4] This is called hemorrhagic or hypovolemic shock, which is a type of shock that occurs when there is not enough blood to reach organs in the body.[5]

Causes

[edit]Internal bleeding can be caused by a broad number of things and can be broken up into three large categories:

- Trauma, or direct injury to blood vessels within the body cavity

- Genetic and acquired conditions, along with various medications, that result in an increased bleeding risk

- Other

Traumatic

[edit]The most common cause of death in trauma is bleeding.[6] Death from trauma accounts for 1.5 million of the 1.9 million deaths per year due to bleeding.[4]

There are two types of trauma: penetrating trauma and blunt trauma.[2]

- Penetrating trauma is the most common cause of vascular injury and can result in internal bleeding. It can occur after a ballistic injury or stab wound. If penetrating trauma occurs in blood vessels close to the heart, it can quickly lead to hemorrhagic or hypovolemic shock, exsanguination, and death.[2]

- Blunt trauma is another cause of vascular injury that can result in internal bleeding. It can occur after a high speed deceleration in an automobile accident.[2][7]

Non-traumatic

[edit]A number of pathological conditions and diseases can lead to internal bleeding. These include:

- Blood vessel rupture as a result of high blood pressure, aneurysms, peptic ulcers, or ectopic pregnancy.[8]

- Other diseases linked to internal bleeding include cancer, hematologic disease, Vitamin K deficiency, and rare viral hemorrhagic fevers, such as the Ebola, Dengue or Marburg viruses.[9]

Other

[edit]

Internal bleeding could be a result of complications following surgery or other medical procedures. Some medications may also increase a person's risk for bleeding, such as anticoagulant drugs or antiplatelet drugs in the treatment of coronary artery disease.[10]

Diagnosis

[edit]Vital signs

[edit]Blood loss can be estimated based on heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and mental status.[11] Blood is circulated throughout the body and all major organ systems through a closed loop system. When there is damage to the blood vessel or the blood is thinner than the physiologic consistency, blood can exit the vessel which disrupts this close-looped system. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) responds in two large ways as an attempt to compensate for the opening in the system. These two actions are easily monitored by checking the heart rate and blood pressure. Blood pressure will initially decrease due to the loss of blood. This is where the ANS comes in and attempts to compensate by contracting the muscles that surround these vessels. As a result, a person who is bleeding internally may initially have a normal blood pressure. When the blood pressure falls below the normal range, this is called hypotension. The heart will start to pump faster causing the heart rate to increase, as an attempt to get blood delivered to vital organ systems faster. When the heart beats faster than the healthy and normal range, this is called tachycardia. If the bleeding is not controlled or stopped, a patient will experience tachycardia and hypotension, which altogether is a state of shock, called hemorrhagic shock.

Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) by the American College of Surgeons separates hemorrhagic shock into four categories.[12][4][13]

| Estimated blood loss | Heart rate (per minute) | Blood pressure | Pulse pressure (mmHg) | Respiratory rate (per minute) | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I hemorrhage | < 15% | Normal or minimally elevated | Normal | Normal | Normal |

|

| Class II hemorrhage | 15 - 30% | 100 - 120 | Normal or minimally decreased systolic blood pressure | Narrowed | 20 - 30 |

|

| Class III hemorrhage | 30 - 40% | 120 - 140 | Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or change in blood pressure > 20-30% from presentation | Narrowed | 30 - 40 |

|

| Class IV hemorrhage | > 40% | > 140 | Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg | Narrowed (< 25 mmHg) | >35 |

|

Assessing circulation occurs after assessing the patient's airway and breathing (ABC (medicine)).[5] If internal bleeding is suspected, a patient's circulatory system is assessed through palpation of pulses and doppler ultrasonography.[2]

Physical examination

[edit]It is important to examine the person for visible signs that may suggest the presence of internal bleeding and/or the source of the bleed.[2] Some of these signs may include:

- a wound

- bruising [ecchymosis]

- blood collection [hematoma]

- abnormal skin sensation [paresthesia]

- signs of compartment syndrome

Imaging

[edit]If internal bleeding is suspected a FAST exam may be performed to look for bleeding in the abdomen.[2][12]

If the patient has stable vital signs, they may undergo diagnostic imaging such as a CT scan.[4] If the patient has unstable vital signs, they may not undergo diagnostic imaging and instead may receive immediate medical or surgical treatment.[4]

Treatment

[edit]Management of internal bleeding depends on the cause and severity of the bleed. Internal bleeding is a medical emergency and should be treated immediately by medical professionals.[2]

Fluid replacement

[edit]If a patient has low blood pressure (hypotension), intravenous fluids can be used until they can receive a blood transfusion. In order to replace blood loss quickly and with large amounts of IV fluids or blood, patients may need a central venous catheter.[12] Patients with severe bleeding need to receive large quantities of replacement blood via a blood transfusion. As soon as the clinician recognizes that the patient may have a severe, continuing hemorrhage requiring more than 4 units in 1 hour or 10 units in 6 hours, they should initiate a massive transfusion protocol.[12] The massive transfusion protocol replaces red blood cells, plasma, and platelets in varying ratios based on the cause of the bleeding (traumatic vs. non-traumatic).[4]

Stopping the bleeding

[edit]

It is crucial to stop the internal bleeding immediately (achieve hemostasis) after identifying its cause.[4] The longer it takes to achieve hemostasis in people with traumatic causes (e.g. pelvic fracture) and non-traumatic causes (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm), the higher the death rate is.[4]

Unlike with external bleeding, most internal bleeding cannot be controlled by applying pressure to the site of injury.[12] Internal bleeding in the thorax and abdominal cavity (including both the intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal space) cannot be controlled with direct pressure (compression). A patient with acute internal bleeding in the thorax after trauma should be diagnosed, resuscitated, and stabilized in the Emergency Department in less than 10 minutes before undergoing surgery to reduce the risk of death from internal bleeding.[4] A patient with acute internal bleeding in the abdomen or pelvis after trauma may require use of a REBOA device to slow the bleeding.[4] The REBOA has also been used for non-traumatic causes of internal bleeding, including bleeding during childbirth and gastrointestinal bleeding.[4]

Internal bleeding from a bone fracture in the arms or legs may be partially controlled with direct pressure using a tourniquet.[12] After tourniquet placement, the patient may need immediate surgery to find the bleeding blood vessel.[4]

Internal bleeding where the torso meets the extremities ("junctional sites" such as the axilla or groin) cannot be controlled with a tourniquet; however there is an FDA approved device known as an Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet (AAJT) designed for proximal aortic control, although very few studies examining its use have been published.[14][15][16][17][18][19] For bleeding at junctional sites, a dressing with a blood clotting agent (hemostatic dressing) should be applied.[4]

A campaign is to improve the care of the bleeding known as Stop The Bleed campaign is also taking place.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ Auerback, Paul. Field Guide to Wilderness Medicine (PDF) (12 ed.). pp. 129–131. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fritz, Davis (2011). "Vascular Emergencies". Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Emergency Medicine (7e ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071701075.

- ^ "DynaMed". www.dynamed.com. Retrieved 2023-10-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Cannon, Jeremy (January 25, 2018). "Hemorrhagic Shock". The New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (4): 370–379. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1705649. PMID 29365303. S2CID 205117992.

- ^ a b International Trauma Life Support for Emergency Care Providers. Pearson Education Limited. 2018. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-1292-17084-8.

- ^ Teixeira, Pedro G. R.; Inaba, Kenji; Hadjizacharia, Pantelis; Brown, Carlos; Salim, Ali; Rhee, Peter; Browder, Timothy; Noguchi, Thomas T.; Demetriades, Demetrios (December 2007). "Preventable or Potentially Preventable Mortality at a Mature Trauma Center". The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 63 (6): 1338–46, discussion 1346–7. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31815078ae. PMID 18212658.

- ^ Duncan, Nicholas S.; Moran, Chris (2010). "(i) Initial resuscitation of the trauma victim". Orthopaedics and Trauma. 24: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.mporth.2009.12.003.

- ^ Lee, Edward W.; Laberge, Jeanne M. (2004). "Differential Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Bleeding". Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 7 (3): 112–122. doi:10.1053/j.tvir.2004.12.001. PMID 16015555.

- ^ Bray, M. (2009). "Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses". Encyclopedia of Microbiology. pp. 339–353. doi:10.1016/B978-012373944-5.00303-5. ISBN 9780123739445.

- ^ Pospíšil, Jan; Hromádka, Milan; Bernat, Ivo; Rokyta, Richard (2013). "STEMI - the importance of balance between antithrombotic treatment and bleeding risk". Cor et Vasa. 55 (2): e135 – e146. doi:10.1016/j.crvasa.2013.02.004.

- ^ Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Emergency Medicine. McGraw-Hill. 2011-05-23. ISBN 978-0071701075.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colwell, Christopher. "Initial management of moderate to severe hemorrhage in the adult trauma patient". UpToDate. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ a b ATLS- Advanced Trauma Life Support - Student Course Manual (10th ed.). American College of Surgeons. 2018. pp. 43–52. ISBN 978-78-0-9968267.

- ^ Croushorn J. Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet controls hemor-rhage from a gunshot wound of the left groin.JSpecOperMed.2014;14(2):6–8.

- ^ Croushorn J, Thomas G, McCord SR. Abdominal aortic tourniquet controlsjunctional hemorrhage from a gunshot wound of the axilla.J Spec Oper Med.2013;13(3):1–4.

- ^ Rall JM, Ross JD, Clemens MS, Cox JM, Buckley TA, Morrison JJ. Hemo-dynamic effects of the Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet in ahemorrhagic swine model.JSurgRes. 2017;212:159–166.

- ^ Kheirabadi BS, Terrazas IB, Miranda N, Voelker AN, Grimm R, Kragh JF Jr,Dubick MA. Physiological Consequences of Abdominal Aortic and Junc-tional Tourniquet (AAJT) application to control hemorrhage in a swinemodel.Shock (Augusta, Ga). 2016;46(3 Suppl 1):160–166.

- ^ Taylor DM, Coleman M, Parker PJ. The evaluation of an abdominal aortictourniquet for the control of pelvic and lower limb hemorrhage.Mil Med.2013;178(11):1196–1201.

- ^ Brannstrom A., Rocksen D., Hartman J., et al Abdominal aortic and junctional tourniquet release after 240 minutes is survivable and associated with small intestine and liver ischemia after porcine class II hemorrhage. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg.. 2018;85(4):717-724. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002013

- ^ Pons, MD, Peter. "Stop the Bleed - SAVE A LIFE: What Everyone Should Know to Stop Bleeding After an Injury". Archived from the original on September 28, 2016.

External links

[edit]Internal bleeding

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

Internal bleeding, also known as internal hemorrhage, refers to the loss of blood from damaged blood vessels that accumulates within the body's tissues, organs, or cavities, remaining invisible from the exterior.[1] This condition arises when blood escapes the circulatory system and pools internally, distinguishing it from external hemorrhage where bleeding is apparent on the skin's surface.[6] Unlike visible wounds, internal bleeding can proceed undetected, progressively reducing blood volume and potentially resulting in hypovolemia.[1] Common anatomical sites for internal bleeding include closed body cavities such as the peritoneal cavity (abdomen), pleural cavity (chest), and pericardial cavity (around the heart), as well as potential spaces like the retroperitoneal area behind the abdominal lining.[7] It may also occur within the gastrointestinal tract, cranial spaces, spinal canal, or surrounding major bones and organs.[6] These locations allow blood to collect without immediate external signs, complicating early recognition.[1] Internal bleeding is broadly classified by severity into mild, moderate, and severe categories, often aligned with the extent of blood loss: mild involving up to 15% of total blood volume with minimal or no symptoms, moderate at 15-30% leading to noticeable effects like tachycardia, and severe exceeding 30% which can cause profound instability.[1] It is further categorized as acute, characterized by sudden and rapid blood loss, or chronic, involving slower accumulation over time.[1] Severe cases may culminate in hemorrhagic shock if untreated.[1]Epidemiology

Internal bleeding represents a significant public health burden, with traumatic hemorrhage accounting for an estimated 1.5 million deaths worldwide each year.[8] This figure constitutes a substantial portion of the approximately 4.4 million annual global deaths from injuries, where hemorrhage contributes to 30-40% of trauma-related fatalities.[9] Regional variations are pronounced, with low- and middle-income countries bearing over 90% of the injury-related burden due to limited access to emergency care, while high-income regions report lower but still notable rates, such as over 60,000 traumatic hemorrhage deaths annually in the United States.[8] Non-traumatic internal bleeding, such as intracerebral hemorrhage, also contributes substantially to global mortality, with an estimated 3.3 million deaths in 2021.[10] Demographic patterns reveal a higher incidence among males, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1, particularly in traumatic cases where males comprise about 80% of patients.[11] Age distributions show peaks in the 15-44 year range for trauma-related internal bleeding, driven by accidents and violence, while non-traumatic forms, such as those from vascular rupture or gastrointestinal sources, predominate in the elderly population over 65 years.[11][12] Urban-rural disparities exist, with urban areas experiencing higher rates of traumatic incidents due to traffic and violence, contrasted by rural challenges from delayed medical access. Trends indicate a rising global incidence, influenced by aging populations that increase non-traumatic cases and the expanding use of anticoagulants, which elevate bleeding risks in older adults.[13] Data from 2016 to 2020 show increases in iatrogenic bleeding, with oral anticoagulant-related emergency visits rising from 230,000 in 2016 to over 300,000 in 2020 as of that period, partly linked to procedural complications amid heightened healthcare demands.[14]Causes

Traumatic causes

Traumatic causes of internal bleeding arise from external forces that disrupt blood vessels or organs, leading to hemorrhage within body cavities or tissues. These injuries are primarily classified into blunt and penetrating trauma, each involving distinct mechanisms of vessel and organ damage. Blunt trauma results from non-penetrating impacts that cause compression, shearing, or tearing forces, while penetrating trauma involves objects that breach the skin and underlying structures.[15][16] Blunt trauma commonly occurs in motor vehicle accidents, falls, and assaults, where rapid deceleration or crushing forces lead to internal injuries. For instance, high-speed collisions can cause splenic or liver lacerations due to the organs' vulnerability to shearing against fixed structures like the spine. Deceleration injuries, such as those from sudden stops in vehicles, may also produce aortic tears at points of mobility, like the ligamentum arteriosum, resulting in massive retroperitoneal or mediastinal bleeding. These mechanisms involve pathophysiological vessel disruption through tensile forces, as detailed in the mechanisms of hemorrhage section.[17][18] Penetrating trauma, often from gunshot or stab wounds to the torso, directly perforates vascular structures or organs, leading to rapid exsanguination. Gunshot wounds create high-velocity tissue disruption and cavitation, frequently injuring major vessels like the aorta or mesenteric arteries, while stab wounds cause linear lacerations that may sever smaller branches or solid organs such as the liver. In the abdomen, these injuries commonly result in mesenteric vessel tears, compromising blood supply to the intestines and causing hemoperitoneum. Thoracic penetration can produce hemothorax through intercostal vessel or lung laceration, exacerbated by associated rib fractures that puncture pleural spaces.[19][20][21] Traumatic internal bleeding accounts for a significant proportion of emergency cases, representing the leading cause of hemorrhage in trauma patients, with sources including abdominal (about 44%), thoracic (20%), and pelvic sites.[22][23] In conflict zones, such as war-affected regions, the incidence is notably higher, with abdominal trauma comprising 18-25% of injuries compared to lower rates in civilian settings.[11][24]Non-traumatic causes

Non-traumatic causes of internal bleeding arise from underlying medical conditions that compromise vascular integrity or hemostatic mechanisms without external injury. These etiologies often involve chronic diseases affecting the gastrointestinal tract, vascular structures, blood clotting processes, or malignancies, leading to spontaneous hemorrhage that can be life-threatening if undetected. Common presentations include gastrointestinal hemorrhage, retroperitoneal bleeding, or organ-specific bleeds, with diagnosis relying on clinical suspicion and imaging or endoscopy. Additionally, gynecological conditions, such as ruptured ectopic pregnancy, can cause severe intraperitoneal bleeding. Infectious diseases, including viral hemorrhagic fevers (e.g., Ebola, dengue), can result in internal bleeding through endothelial dysfunction and disseminated intravascular coagulation.[25][1] Gastrointestinal sources are among the most frequent non-traumatic causes, particularly peptic ulcers, which erode the mucosal lining of the stomach or duodenum, resulting in upper gastrointestinal bleeding that manifests as hematemesis or melena. Approximately one-quarter of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages stem from peptic ulcer disease, often exacerbated by factors like Helicobacter pylori infection or chronic NSAID use, though the bleeding itself is endogenous.[26] Esophageal or gastric varices, typically secondary to portal hypertension from liver cirrhosis, can rupture and cause massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with variceal hemorrhage accounting for up to 10-20% of such cases in affected populations.[25] In the lower gastrointestinal tract, diverticulosis leads to bleeding in about 3-15% of patients with colonic diverticula, where fragile vasa recta vessels at the diverticular neck rupture, often presenting as painless hematochezia and contributing to nearly 200,000 annual hospital admissions in the United States.[27][28] Vascular disorders represent another critical category, where structural weaknesses in major arteries predispose to dissection or rupture. Aortic dissection involves a tear in the intima of the aorta, allowing blood to enter the media and create a false lumen, which can extend and lead to hemorrhage into the mediastinum, pleura, or retroperitoneum, occurring spontaneously in conditions like hypertension or connective tissue disorders.[29] Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, prevalent in elderly individuals with atherosclerosis, cause rapid retroperitoneal or intraperitoneal bleeding; these aneurysms affect about 1-2% of people over 65, with rupture mortality exceeding 80% due to exsanguination if untreated.[30][31] Hematological coagulopathies disrupt normal clotting, promoting spontaneous internal bleeding in joints, muscles, or viscera. Hemophilia A and B, inherited deficiencies of factor VIII or IX respectively, result in hemarthrosis and intramuscular hematomas as hallmark spontaneous bleeds, affecting approximately 1 in 5,000 males and leading to recurrent internal hemorrhages without trauma.[32] Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), an acquired syndrome often triggered by sepsis, malignancy, or obstetric complications, consumes clotting factors and platelets, causing widespread microvascular thrombosis followed by bleeding into organs or the gastrointestinal tract.[33][34] Oncologic conditions contribute through direct tumor invasion or erosion into vascular structures, precipitating hemorrhage. In pancreatic cancer, tumor growth can invade the gastroduodenal artery or erode into the duodenum, causing severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding in up to 10-20% of advanced cases, often as a presenting feature.[35] Hepatic cancers, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, may rupture spontaneously due to rapid tumor expansion and necrosis, leading to hemoperitoneum; this occurs in 3-15% of patients with large tumors and carries a high mortality rate from acute blood loss.[36]Iatrogenic causes

Iatrogenic causes of internal bleeding arise from medical interventions, including surgical procedures, pharmacological therapies, and diagnostic or therapeutic interventions, which can disrupt vascular integrity or impair hemostatic mechanisms. These complications, though relatively uncommon, contribute significantly to morbidity in hospitalized patients, often requiring urgent reintervention. Unlike spontaneous or traumatic hemorrhages, iatrogenic bleeding is directly linked to healthcare delivery, with risks amplified by patient factors such as underlying conditions or procedural complexity.[37] Surgical complications represent a primary iatrogenic source, particularly postoperative hemorrhage due to inadequate hemostasis during vessel ligation or tissue manipulation. For instance, after splenectomy, bleeding may occur from the splenic hilum or accessory vessels, with reported incidences ranging from 1.6% to 3% in large series, often necessitating return to the operating room within the first 24 hours. Injuries to abdominal or pelvic veins during oncologic resections or procedures involving difficult anatomic exposure, such as prior surgeries or radiation-altered tissues, further elevate risks, occurring in up to 65% of venous injury cases attributed to these factors. These events can lead to intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal accumulation, exacerbating hemodynamic instability.[38][39] Pharmacological agents, notably anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs, substantially increase the propensity for internal bleeding by inhibiting coagulation pathways. Warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, is associated with major bleeding events in approximately 2-3% of users annually, while direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) like apixaban or rivaroxaban show comparable or slightly lower rates but still elevate risks when combined with antiplatelets. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin alone heightens gastrointestinal or intracranial bleed likelihood by 50-100% in susceptible populations, and dual or triple regimens (e.g., aspirin plus clopidogrel and a DOAC) can amplify major bleeding incidence to 10% or more in the first year post-initiation, particularly in patients with atrial fibrillation or recent stents. These risks are dose-dependent and often manifest as retroperitoneal or intra-abdominal hemorrhages.[40][41] Interventional procedures, such as angiography and endoscopy, carry risks of vascular perforation or puncture-site hemorrhage. Femoral artery access during coronary angiography can result in retroperitoneal hematoma in 0.2-0.6% of cases, a potentially life-threatening accumulation that may exceed 1 liter and cause hypovolemic shock if undetected. Endoscopic interventions like colonoscopy or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) similarly predispose to retroperitoneal bleeding, with incidences of 1-2% for post-ERCP hemorrhage, often from sphincterotomy sites or inadvertent duodenal perforation. These complications are more frequent in anticoagulated patients or those with procedural technical challenges.[42][43][44] Post-2020, iatrogenic bleeding incidents have risen in certain cohorts due to heightened use of invasive procedures amid the COVID-19 pandemic, including mechanical ventilation support and vascular access for therapeutics. In critically ill COVID-19 patients, iatrogenic arterial bleeding occurred in about 30% of embolization cases, frequently following chest tube insertions or central line placements, correlating with overall procedural volume surges. This trend underscores the interplay with pandemic-related coagulopathies, amplifying intervention-associated risks.[45][46]Pathophysiology

Mechanisms of hemorrhage

Internal bleeding begins with the failure of vessel integrity, where blood vessels rupture, erode, or become fragile, allowing blood to extravasate into surrounding tissues or body cavities. This process can occur due to mechanical disruption, such as tears in vessel walls, or degenerative changes like weakening of arterial walls in aneurysms. For instance, in hypertensive conditions, elevated intravascular pressure can exceed the tensile strength of the vessel wall, leading to rupture and subsequent hemorrhage.[4][1][47] Disruption of the coagulation cascade further exacerbates hemorrhage by impairing the body's hemostatic response. Hemostasis normally involves platelet adhesion and aggregation to form a primary plug, followed by activation of the coagulation factors—such as fibrinogen converting to fibrin—to stabilize the clot. Failures in this cascade, including deficiencies in clotting factors (e.g., factors VIII or IX) or impaired platelet function, prevent effective clot formation, allowing bleeding to continue unchecked. Conditions like trauma-induced coagulopathy, characterized by dilution of coagulation factors, acidosis, and hypothermia, compound this disruption, leading to widespread hemostasis failure.[48][47][4] Pressure dynamics play a critical role in initiating and propagating hemorrhage, as the force exerted by blood against vessel walls determines whether a weakened site will breach. In scenarios like aneurysmal rupture, chronic hypertension increases wall stress, often following Laplace's law where tension is proportional to pressure and radius, predisposing to failure. Once initiated, the pressure gradient between the vascular lumen and surrounding tissues drives continued extravasation.[4][47] The physics of volume loss governs the initial rate of bleeding, influenced by the size of the vessel defect and the pressure gradient across it. According to Poiseuille's law, blood flow through the breach is proportional to the fourth power of the radius and the pressure difference, divided by the length of the vessel segment, meaning even small increases in opening size dramatically accelerate hemorrhage. For example, arterial bleeds from larger vessels, such as the femoral artery, can result in rapid exsanguination due to high flow rates under systemic pressure. Traumatic vessel tears, as one trigger, can initiate this process by creating such defects.[4][49]Hemodynamic consequences

Internal bleeding leads to hypovolemia, a reduction in intravascular volume that impairs cardiac output and tissue perfusion, progressing through four classes of hemorrhagic shock as classified by the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines.[4] Class I involves up to 15% blood volume loss (approximately 750 mL in adults), with minimal hemodynamic changes and no significant clinical effects.[4] Class II entails 15-30% loss (750-1500 mL), marked by early compensatory tachycardia and anxiety but maintained blood pressure.[4] In Class III, 30-40% volume loss (1500-2000 mL) results in tachycardia exceeding 120 beats per minute, hypotension, and decreased urine output, indicating substantial circulatory compromise.[4] Class IV, exceeding 40% loss (>2000 mL), features profound hypotension, rapid thready pulse, and obtundation, often leading to imminent cardiovascular collapse.[4] The body initially responds to hypovolemia through sympathetic nervous system activation, triggering vasoconstriction to redistribute blood to vital organs and tachycardia to sustain cardiac output.[50] This is augmented by neuroendocrine mechanisms, including increased antidiuretic hormone release to promote fluid retention and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation to enhance vasoconstriction and sodium conservation.[50] These compensatory responses maintain perfusion during early stages but eventually fail as blood loss exceeds 30-40%, leading to decompensation with widespread organ hypoperfusion.[51] Prolonged hypoperfusion causes organ-specific dysfunction; renal blood flow decreases, precipitating acute kidney injury through ischemia and tubular necrosis.[52] Cerebral hypoperfusion manifests as altered mental status, such as confusion, due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the brain.[50] In cases of pericardial hemorrhage, blood accumulation compresses the heart, causing cardiac tamponade with impaired diastolic filling and reduced stroke volume.[53] Hemorrhagic shock progresses from compensated (Classes I-II) to progressive decompensated (Class III) and irreversible stages (Class IV), where cellular damage and metabolic acidosis become self-perpetuating, leading to multi-organ failure.[4] Mortality escalates sharply beyond 40% volume loss, with survival rates dropping exponentially as irreversible hypoperfusion sets in, often resulting in death within hours if untreated.[4]Signs and symptoms

Early manifestations

Early manifestations of internal bleeding often arise from mild hypovolemia, typically involving less than 20% of total blood volume loss, where the body activates compensatory mechanisms to maintain perfusion to vital organs.[4] Common general symptoms during this phase include fatigue, lightheadedness, and anxiety, which reflect the initial physiological response to reduced circulating volume without progression to overt shock.[1] These symptoms stem from sympathetic nervous system activation, which prioritizes blood flow to the brain and heart while causing subtle systemic effects.[4] Localized clues provide site-specific indicators that may appear early, depending on the bleeding's location. For example, hemoperitoneum can cause abdominal distension due to blood accumulation in the peritoneal cavity, presenting as a sensation of fullness or mild swelling.[1] Similarly, hemothorax may manifest as shortness of breath from blood irritating the pleural space and compressing the lung, occurring without immediate hemodynamic instability. In cases of thoracic trauma, such as from a severe fall, early signs may include coughing up bright red frothy blood (hemoptysis), chest pain, difficulty breathing with gurgling or whistling sounds, and shallow erratic breaths.[5][54] These signs highlight the importance of considering the injury site in early recognition. Behavioral changes, such as restlessness and pallor, frequently accompany early internal bleeding as a result of catecholamine release, which induces peripheral vasoconstriction and heightened alertness.[4] Pallor arises from reduced skin blood flow, while restlessness signals the body's stress response to hypovolemia. These manifestations typically emerge within minutes to hours following the onset of bleeding, often before significant vital sign changes like pronounced tachycardia or hypotension develop.[4] This early window allows for potential intervention prior to advancement in hypovolemic progression.[1]Location-specific symptoms

Symptoms of internal bleeding vary depending on the site of the hemorrhage and can provide important clues to the location of bleeding. Common location-specific manifestations include:- Lungs: Coughing up blood (hemoptysis), shortness of breath, chest pain.[1]

- Esophagus and stomach: Vomiting blood (bright red or coffee-ground appearance), black tarry stools (melena), abdominal pain.[55]

- Liver and spleen: Abdominal pain, swelling or distension, bruising, signs of shock (dizziness, rapid pulse, weakness).[1][5]

- Kidneys and bladder: Blood in urine (hematuria), flank or lower abdominal pain.[1]

- Pelvic cavity: Pelvic or lower abdominal pain, possible blood in urine or stool, swelling.[1]