Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kutenai

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| People | Ktunaxa |

|---|---|

| Language | Ktunaxa, ʔa·qanⱡiⱡⱡitnam |

| Country | Ktunaxa ʔamakʔas |

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

|

|

The Kutenai (/ˈkuːtəneɪ, -niː/ KOO-tə-nay, -nee),[4][5] also known as the Ktunaxa (/tʌˈnɑːhɑː/ tun-AH-hah;[6] Kutenai: [ktunʌ́χɑ̝]), Ksanka (/kəˈsɑːnkɑː/ kə-SAHN-kah), Kootenay (in Canada) and Kootenai (in the United States), are an indigenous people of Canada and the United States. Kutenai bands live in southeastern British Columbia, northern Idaho, and western Montana. The Kutenai language is a language isolate, thus unrelated to the languages of neighboring peoples or any other known language.

Four bands form Ktunaxa Nation in British Columbia. The Ktunaxa Nation was historically closely associated with the Shuswap Indian Band through tribal association and intermarriage. Two federally recognized tribes represent Kutenai people in the U.S.: the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) in Montana, a confederation also including Bitterroot Salish and Pend d'Oreilles bands.

Name

[edit]Around 40 variants of the name Kutenai have been attested since 1820; two others are also in current use. Kootenay is the common spelling in British Columbia, including in the name of the Lower Kootenay First Nation. Kootenai is used in Montana and Idaho, including in the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. These two spellings have been used for various placenames on their respective sides of the Canadian-U.S. border, notably the Kootenay River, called the Kootenai River in the United States.[7] Kutenai is the common form in the literature about the people, and has been adopted by Kutenai in both countries as an international spelling when discussing the people as a whole.[7][8] The name evidently derives from the Blackfoot word for the people, Kotonáwa, which itself may derive from the Kutenai term Ktunaxa.[7][8] This is supported by an interview with Vernon Finley, previous tribal chairman of the CSKT. He supposes the term to be "given... by some other tribe" and that it was likely "a mispronunciation of whatever that word is," since 'Kootenai' holds no meaning in any neighboring language.[9]

In the Kutenai language, Ktunaxa is considered the most correct general term for the culture and peoples. Differing etymologies have been suggested, tying the name to the verb for "eating food plain, [meaning] without seasoning," or alternately to the verb for "licking up blood."[9] In the same interview referenced above, Finley attests the latter meaning to the image of a Ktunaxa warrior shooting an enemy, drawing out the arrow, and licking the blood from the arrowhead.[9] He also says that, historically, people identified themselves primarily with the name of their band and less so with the broad term Ktunaxa.

It has been attested that some Columbian Plateau groups may have called themselves "Upnuckanick."[10] Ksanka, meaning "people of the standing arrow" is the name of the southeastern-most of the seven bands, who are today primarily associated with what is now northwestern Montana, and are politically organized within the CSKT.[9]

Communities

[edit]Four Kutenai bands live in southeastern British Columbia, one lives in northern Idaho, and one lives in northwestern Montana:

- The Ktunaxa Nation Council (KNC) (until 2005 the Ktunaxa/Kinbasket Tribal Council)[11] includes the four Canadian bands:

- Ɂakisq̓nuk First Nation ("place of two lakes"; also known as the Columbia Lake Indian Band).[12] An Upper Kutenai group, they are headquartered in Akisqnuk, south of Windermere. Reserves include: Columbia Lake #3, St. Mary's #1A, ca. 33 km2, population: 264)[13]

- Lower Kootenay Band, (Yaqan Nukiy or Lower Kootenay First Nation).[14] A Lower Kutenai group, they are headquartered in Creston, on the most populous reserve Creston #1 along the Kootenay River, ca. 6 km north of the US-Canada border. Reserves include: Creston #1, Lower Kootenay #1A, #1B, #1C, #2, #3, #5, #4, St. Mary's #1A, ca. 26 km2, population: 214)

- ʔaq̓am First Nation ("deep dense woods").[15] An Upper Kutenai group, they live along the St. Mary's River near Cranbrook. Tribal headquarters are located on the most populous reserve, Kootenay #1; reserves include: Bummers Flat #6, Cassimayooks (Mayook) #5, Isidore's Ranch #4, Kootenay #1, St. Mary's #1A, ca. 79 km2, population: 357)

- Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi’it First Nation (Tobacco Plains First Nation, ʔa·kanuxunik, Akan'kunik, or ʔakink̓umⱡasnuqⱡiʔit - 'People of the place of the flying head'.[16] An Upper Kutenai band, they live near Grasmere on the east shore of the Lake Koocanusa below the mouth of Elk River, ca. 15 km north of the British Columbia-Montana border. Reserves include: St. Mary's #1A, Tobacco Plains #2, ca. 44 km2, population: 165)[17]

Additionally, the Shuswap Indian Band were formerly part of the Ktunaxa Nation. They are a Secwepemc (Shuswap) band who settled in Kutenai territory in the mid-19th century. They were eventually incorporated into the group and intermarried with them, and spoke the Kutenai language. They departed the Ktunaxa nation in 2004 and are now part of the Shuswap Nation Tribal Council. They are located near Invermere, just northeast of Windermere Lake; their reserves include: St. Mary's #1A, Shuswap IR, ca. 12 km2, population: 244).

- Kootenai Tribe of Idaho[18] (ʔaq̓anqmi or ʔa·kaq̓ⱡahaⱡxu, also called Idaho Ksanka). A Lower Kutenai group, they govern the Kootenai Indian Reservation in Boundary County. Their population is 75.

- Kootenai (K̓upawiȼq̓nuk or Ksanka) are members of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, along with Bitterroot Salish and Pend d'Oreilles bands.[19] An Upper Kutenai group, they live mostly on the Flathead Reservation in western Montana. A total population of about 6,800 live on the reservation, while 3,700 live outside the reservation nearby.

History

[edit]The Kutenai today live in southeastern British Columbia, Idaho, and Montana. They are loosely divided into two groups: the Upper Kutenai and the Lower Kutenai, referring to the different sections of the Kootenay River (spelled "Kootenai" in the U.S.) where the bands live. The Upper Kutenai are the Ɂakisq̓nuk First Nation (Columbia Lake Band), the ʔaq̓am First Nation (St. Mary's First Nation), and the Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi’it First Nation (Tobacco Plains Band) in British Columbia, as well as the Montana Kootenai. The Lower Kutenai are the Lower Kootenay First Nation of British Columbia and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho.[20]

Origins

[edit]Scholars have numerous ideas about the origins of the Ktunaxa. One theory is that they originally lived on the prairies, and were driven across the Rockies by the competing Blackfoot people[21] or by famine and disease.[22] Some Upper Kootenay participated in a Plains Native lifestyle for part of the year, crossing the Rockies to the east for the bison hunt. They were relatively well known to the Blackfoot, and sometimes their relations with them were in the form of violent confrontation over food competition.

Some Ktunaxa remained on or returned to the prairies year-round; they had a settlement near Fort Macleod, Alberta. This group of Ktunaxa suffered high mortality rates, partly because of the depredations of the Blackfoot, and partly because of smallpox epidemics. With numbers sharply reduced, these Plains Ktunaxa returned to the Kootenay region of British Columbia.[citation needed]

Some of the Ktunaxa say that their ancestors came originally from the Great Lakes region of Michigan. To date, scholars have not found either archeological or historic evidence to support this account.[citation needed]

The Ktunaxa territory in British Columbia has archeological sites with some of the oldest human-made artifacts in Canada, dated to 11,500 before the present (BP). It has not been proven whether these artifacts were left by ancestors of the Ktunaxa or by another, possibly Salishan, group. [citation needed] Human occupation of the Kootenay Rockies has been demonstrated by dated sites with evidence of quarrying and flint-knapping, especially of quartzite and tourmaline.[citation needed] This oldest assemblage of artifacts is known as the Goatfell Complex, named after the Goatfell region about 40 km east of Creston, British Columbia on Highway 3. These artifacts have been found at quarries in Goatfell, Harvey Mountain, Idaho, Negro Lake and Kiakho Lake (both near Lumberton and Cranbrook), North Star Mountain just west of Creston on Highway 3, and at Blue Ridge. All these sites are within 50 km of Creston, with the exception of Blue Ridge, which is near the village of Kaslo, quite a distance north on the west side of Kootenay Lake.

Archaeologist Dr. Wayne Choquette believes that the artifacts represented in the Goatfell Complex, dated from 11,500 BP up to the early historical period, show that there has been no break in the archaeological record. In addition, he says that it appears that the technology was local. No evidence supports the conjecture that the region's first inhabitants emigrated from this area, nor that they were replaced or succeeded by a different people. Choquette concludes that the Ktunaxa today are the descendants of those first people to inhabit the land.[citation needed]

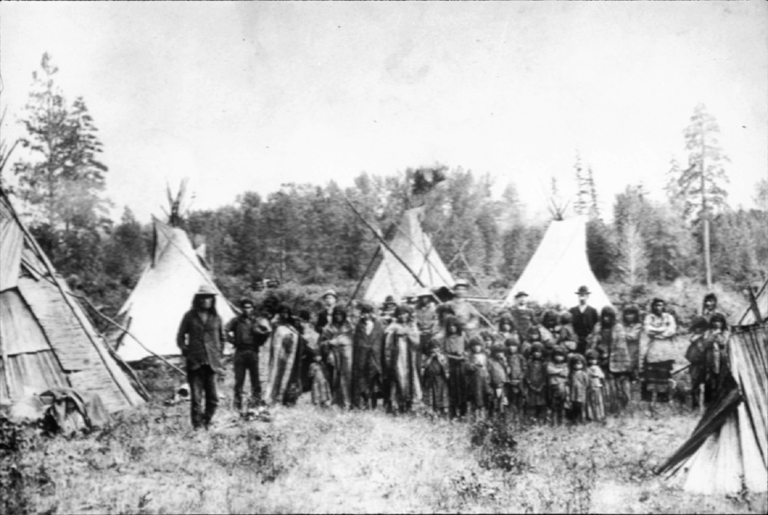

Other scholars, such as Reg Ashwell, suggest that the Ktunaxa moved to the British Columbia region in the early half of the 18th century, having been harassed and pushed there from East of the Rockies by the Blackfoot. He notes that their language is isolated from that of Salish tribes common to the Pacific Coast. In addition, their traditional dress, many of their customs (such as their use of teepee-style portable dwellings), and their traditional religion have more in common with Plains peoples than with the Coastal Salish.[23]

The Goatfell assemblage of artifacts suggests that prior to 11,500 BP, the people who came to inhabit the Kootenay mountains may have lived in what is now the southwestern United States, during a period when British Columbia was beneath the Cordilleran ice sheet of the last ice age. The Goatfell Complex, and specifically the techniques of manufacture of the tools and points, are part of a tradition of knapping that existed in the North American Great Basin and the intermontane west of the continent in the late Pleistocene. The prevailing theory is that as the glaciers retreated, people moved northward, following the revival of the flora and fauna to the north.[citation needed]

From the time of the first Ktunaxa settlement in the Kootenays, until the historical period beginning in the late 18th century, there is little known of the people's social, political, and intellectual development. Stone tool technologies changed and became more complex and differentiated.[citation needed] They were probably big game hunters in their earliest prehistoric phase. The Ktunaxa were first noted in the historical record when mentioned on Alexander Mackenzie's map, circa 1793.[citation needed]

As temperatures continued to warm, the glacial lakes drained and fish found habitat in the warmer waters. The Lower Kootenay across the Pacific Northwest made fishing a fundamental part of their diet and culture, while maintaining the old traditions of game hunting.[citation needed]

Early history

[edit]

Anthropological and ethnographic interest in the Ktunaxa were recorded from the mid-19th century. What these European and North American scholars recorded has to be viewed with a critical eye, since they did not have the theoretical sophistication expected of anthropologists today. They imputed much of their own cultural values into what they were able to observe among the Ktunaxa. But their accounts are the most detailed descriptions of Ktunaxa lifestyles at a time when Aboriginal lifeways all over the world were dramatically changing in the face of settlement by Europeans and European Americans.[citation needed]

The earliest ethnographies detail Ktunaxa culture around the turn of the 20th century. Europeans observed the Ktunaxa enjoying a stable economic life and rich social life, based on a detailed ritual calendar. Their economic life focused on fishing, using fish traps and hooks, and travelling on the waterways in the sturgeon-nosed canoe. They had seasonal and sometimes ritual hunts for bear, deer, caribou, gophers, geese, and the many other fowl in Lower Kootenay country. As mentioned above, the Upper Kootenay often crossed the Rockies to participate in the bison hunt. The Lower Kootenay, however, did not participate in communal bison hunts; these were not important to their economy or culture.[citation needed]

The Ktunaxa conducted vision quests, particularly by a young man in a passage to adulthood. They used tobacco ritually. They practiced a Sun Dance and Grizzly Bear Dance, a midwinter festival, a Blue Jay Dance, and other social and ceremonial activities.[citation needed] The men belonged to different societies or lodges, such as the Crazy Dog Society, the Crazy Owl Society, and the Shamans' Society. These groups took on certain responsibilities, and membership in a lodge came with obligations in battle, hunting, and community service.

The Ktunaxa and their neighbors the Sinixt both used the sturgeon-nosed canoe. This water craft was first described in 1899 as having some similarity to canoes used in the Amur region of Asia.[24] At the time, some scholars believed in a theory of dispersal, concluding that similarities of artifacts or symbols among cultures represented that a superior culture had transmitted its elements to another culture. Since then, however, most scholars have concluded that many such innovations arose independently among different cultures.

Harry Holbert Turney-High, the first to write an extensive ethnography of the Ktunaxa (focusing on bands in the United States), records a detailed description of the harvesting of bark to make this canoe (67):

A tree ... growing rather high in the mountains is sought. Finding one of the desired size and quality, a man climbed it to the proper height and cut a ring around the bark with his elk-horn chisel or flint knife. In the meantime a helper cut out another ring at the base of the tree. This done, an incision was made down the length of the trunk connecting the two rings. This cut had to be as straight and accurate as possible. A stick of about two inches in diameter was used carefully to pry the bark from the tree. The bark was wrapped up so that it would not dry out on the way to camp. The inside, or tree-side of the bark sheet, became the outside of the canoe, while the outside surface became the inside of the boat. The bark was considered ready for immediate use. There was no scraping or seasoning, nor was it decorated in any way.

Christian missionaries traveled to the Ktunaxa territories and worked to convert the peoples, keeping extensive written records of the process and of their observations of the culture. As a result of their accounts, there is more information about the missionary process than about other aspects of Ktunaxa history at the turn of the 20th century.

The Ktunaxa had been exposed to Christianity as early as the 18th century, when a Lower Kootenay prophet from Flathead Lake in Montana by the name of Shining Shirt spread news of the coming of the 'Blackrobes' (French Jesuit missionaries) (Cocolla 20). Ktunaxa people also encountered Christian Iroquois sent west by the Hudson's Bay Company. By the 1830s the Ktunaxa had begun to adopt certain Christian elements in a syncretic blend of ceremonies. They were influenced less by European missionaries than through their contact with Christian Natives from other parts of Canada and the United States.

Father Pierre-Jean de Smet in 1845-6 was the first missionary to tour the region. He intended to establish missions to minister to Native peoples, and assessing the success and needs of those already established.[citation needed] The Catholic Jesuits had made it a priority to minister to these newly discovered peoples in the New World. While there was missionary activity in Eastern North America for 200 years, the Ktunaxa were not the objects of the church's attentions until the mid-late 19th century. Following De Smet, a Jesuit named Philippo Canestrelli lived among the Ksanka people of Montana in the 1880s and 90s. He wrote a much celebrated grammar of their language, published in 1896. The first missionary to take up a permanent post in the Yaqan Nu'kiy territory, i.e. the Creston Band of Lower Kootenay, was Father Nicolas Coccola, who arrived in the Creston area in 1880. His memoirs, corroborated by newspaper reports and Ktunaxa oral histories, are the basis for the early 20th-century history of the Ktunaxa.

In the first stages of Ktunaxa-European contact, mainly the result of a gold rush that began in earnest in 1863 with the discovery of gold in Wild Horse Creek, the Ktunaxa were little interested in European-driven economic activities. Traders worked to recruit them to trap in support of the fur trade, but few Lower Kootenay found this worthwhile. The Lower Kootenay region is, as mentioned above, remarkably rich in fish, birds, and large game. As the economic life of the Yaqan Nu'kiy was notably secure, they resisted new and unfamiliar economic activities.

Slowly though, the Yaqan Nu'kiy began participating in European-driven industries. They served as hunters and guides for the miners at the Bluebell silver-lead mine at Riondel. The richest gold mine ever discovered in the Kootenays was discovered by a Ktunaxa man named Pierre, and staked by him and Father Coccola in 1893.[citation needed]

20th century

[edit]While there was sometimes conflict between the Yaqan Nu'kiy and the local settler community at Creston, their relations were more characterized by peaceful coexistence. Their conflicts tended to be over land use. In contrast, relations between the Lower Kootenay and the surrounding European society in Bonners Ferry, Idaho, deteriorated.

By the turn of the 20th century, some Yaqan Nu'kiy were engaged in agricultural activities introduced by European settlers, but their approach to the land was different. An example of the type of conflict that repeatedly arose between European settlers and Native farmers is shown by a newspaper article in the Creston Review dated Friday, 9 August 1912:

A dispute over the rights to cut hay on the flat lands, between the Indians and the white men, which might have resulted in bloodshed, was settled Wednesday by W.F. Teetzel, government agent, of Nelson, who told both Indians and whites that if violence is done, no one would be allowed to cut hay on government land. ... The principal trouble this year occurred when some Indians threatened Frank Lewis and drove him from the hay he had already cut. The Indians claim they have cut land at this particular place for years while the old-time ranchers say that hay has never before been cut there. Mr. Lewis complained to Policeman Gunn who, as the definite boundry [sic] of the Indian reservation is not known was at a loss what to do because no violence was committed whereby he could act. ... Mr. Teetzel arrived from Nelson Wednesday and in conference with Chief Alexander, got him to promise to see that Mr. Lewis got his hay, and warned him to keep the Indians from violence under penalty of losing the right of cutting hay on the flats. This warning he also gave to the white men. This is not the only one of the cases occurring this year. One farmer whose place is located near the reservation has been continually bothered by the Indians cutting his fences and turning their cattle in to graze on his property.

The Creston Review, also reported on 21 June 1912: "[Indian Agent Galbraith] says everything is in good condition and the majority of the Indians are at work picking berries for the ranchers who find their help useful and profitable."

These examples illustrate the dynamic of relations between two peoples: the Ktunaxa whose lands have been vastly reduced by the introduction of a reserve system, and the European settlers who are constantly looking to expand their access to the land (and later industries).

During the 20th century the Yaqan Nu'kiy gradually became involved in all the industries of the Creston valley: agriculture, forestry, mining, and later health care, education, and tourism. This process of integration separated the Yaqan Nu'kiy from their traditional lifeways, yet they have remained a very successful and self-confident community. They gradually gained more control and self-government, with less involvement from the Department of Indian or Aboriginal Affairs. Like most tribes in British Columbia, the Yaqan Nu'kiy did not have a treaty defining their rights regarding their territory. They have been working for decades on a careful and more or less cooperative treaty negotiation process with the government of Canada.[citation needed] The Creston Band of the Ktunaxa today has 113 individuals living on the reserve, and many others living off-reserve and working in various industries in Canada and the United States.[citation needed]

Feeling that they have lost some traditions that are very important to them, the Ktunaxa are working to revive their culture, and particularly to encourage language study. A total of 10 fluent speakers of Ktunaxa live in both the U.S. and Canada. The Yaqan Nu'kiy have developed a language curriculum for grades 4–6, and have been teaching it for four years, to develop a new generation of native speakers. They are involved in designing curriculum for grades 7–12, which requires meeting B.C. curriculum guidelines. Concurrent with this, they are recording oral stories and myths, as well as to videotaping the practice of their traditional crafts and technologies, with spoken directions.

"Kootenai Nation War"

[edit]On 20 September 1974, the Kootenai Tribe headed by Chairwoman Amy Trice declared war on the United States government. Their first act was to post tribal members on each end of U.S. Highway 95 that runs through the town of Bonners Ferry. They asked motorists to pay a toll to drive through the land that had been the tribe's aboriginal land. (About 200 Idaho State Police were on hand to keep the peace and there were no incidents of violence.) They intended to use the toll money to house and care for elderly tribal members. Most tribes in the United States are forbidden to declare war on the U.S. government because of treaties, but the Kootenai Tribe never signed a treaty.

The United States government ultimately made a land grant of 12.5 acres (0.051 km2), the basis of what is now the Kootenai Reservation.[25] In 1976 the tribe issued "Kootenai Nation War Bonds" that sold at $1.00 each. The bonds were dated 20 September 1974 and contained a brief declaration of war on the United States. These bonds were signed by Amelia Custack Trice, Tribal Chairwoman, and Douglas James Wheaton Sr., Tribal Representative. They were printed on heavy paper stock and were designed and signed by the western artist Emilie Touraine.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation

- Kootanae House, early fur trade post associated with the Kootenai tribe

- Kootenays

- Kutenai language

- Kaúxuma Núpika

- Jennifer Porter

- Salish Kootenai College

Literature

[edit]- Boas, Franz, and Alexander Francis Chamberlain. Kutenai Tales. Washington: Govt. Print. Off, 1918.

- Chamberlain, A. F., "Report of the Kootenay Indians of South Eastern British Columbia," in Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, (London, 1892)

- Finley, Debbie Joseph, and Howard Kallowat. Owl's Eyes & Seeking a Spirit: Kootenai Indian Stories. Pablo, Mont: Salish Kootenai College Press, 1999. ISBN 0-917298-66-7

- Kootenai Culture Committee (Autumn 2015). "The Traditional Worldview of the Kootenai People". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 65 (3). Helena, Montana: Montana Historical Society Press: 47–73.

- Linderman, Frank Bird, and Celeste River. Kootenai Why Stories. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. ISBN 0-585-31584-1

- Maclean, John, Canadian Savage Folk, (Toronto, 1896)

- Tanaka, Beatrice, and Michel Gay. The Chase: A Kutenai Indian Tale. New York: Crown, 1991. ISBN 0-517-58623-1

- Thompson, Sally (2015). People Before The Park-The Kootenai and Blackfeet Before Glacier National Park. Helena, Montana: Montana Historical Society Press.

- Turney-High, Harry Holbert. Ethnography of the Kutenai. Menasha, Wis: American Anthropological Association, 1941.

References

[edit]- ^ "Aboriginal Ancestry Responses (73), Single and Multiple Aboriginal Responses (4), Residence on or off reserve (3), Residence inside or outside Inuit Nunangat (7), Age (8A) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2016 Census - 25% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Government of Canada. 25 October 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Auld, Francis. "ʾa·qanⱡiⱡⱡitnam". Facebook (in Kutenai). Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "Kutenai". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins.

- ^ "Kutenai". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Pronunciation Guide to First Nations in British Columbia". Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. 15 September 2010. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Morgan, Lawrence Richard (1991). A Description of the Kutenai Language (PhD). University of California. p. 1.

- ^ a b McMillan, Alan D.; Yellowhorn, Eldon (2009). First Peoples in Canada. D & M Publishers. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-926706-84-9.

- ^ a b c d Thompson, Sally (director). "Tribes of Montana" (2007), The Montana Experience: Stories From Big Sky Country, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YgEvbYgGfus

- ^ PBS, Uncharted Territory: David Thompson on the Columbia Plateau on YouTube, Narrative of David Thompson's life and travels. / Feb 2011, minutes: 14:13–14:20

- ^ Ktunaxa Nation

- ^ "Akisqnuk: Our Community" Archived 26 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. www.akisqnuk.com. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ Source for Population: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), Registered Population as of June, 2011

- ^ "Lower Kootenay First Nation". lowerkootenay.com. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "Aqam - About". www.aqam.net

- ^ Tobacco Plains Band Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aboriginal Canada - First Nation Connectivity Profile Archived 6 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Kootenai Tribe of Idaho". Archived from the original on 29 October 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ "Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation". www.csktribes.org. Retrieved 31 May

- ^ Morgan, Lawrence Richard (1991). A Description of the Kutenai Language (PhD). University of California. p. 3.

- ^ Anderson, Frank W. (1972). The Dewdney Trail. Canada: Frontier Press. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Reg Ashwell, Indian Tribes of British Columbia, Hancock House (1977/2012), p. 55

- ^ Mason in Rep. Nat. Mus., 1899, 19 June 2012

- ^ Idaho's forgotten war Archived 18 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, University of Idaho

External links

[edit]- Official website of the Ktunaxa Nation

- Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Archived 29 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine, official website