Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Orthogonal group

View on Wikipedia| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In mathematics, the orthogonal group in dimension n, denoted O(n), is the group of distance-preserving transformations of a Euclidean space of dimension n that preserve a fixed point, where the group operation is given by composing transformations. The orthogonal group is sometimes called the general orthogonal group, by analogy with the general linear group. Equivalently, it is the group of n × n orthogonal matrices, where the group operation is given by matrix multiplication (an orthogonal matrix is a real matrix whose inverse equals its transpose). The orthogonal group is an algebraic group and a Lie group. It is compact.

The orthogonal group in dimension n has two connected components. The one that contains the identity element is a normal subgroup, called the special orthogonal group, and denoted SO(n). It consists of all orthogonal matrices of determinant 1. This group is also called the rotation group, generalizing the fact that in dimensions 2 and 3, its elements are the usual rotations around a point (in dimension 2) or a line (in dimension 3). In low dimension, these groups have been widely studied, see SO(2), SO(3) and SO(4). The other component consists of all orthogonal matrices of determinant −1. This component does not form a group, as the product of any two of its elements is of determinant 1, and therefore not an element of the component.

By extension, for any field F, an n × n matrix with entries in F such that its inverse equals its transpose is called an orthogonal matrix over F. The n × n orthogonal matrices form a subgroup, denoted O(n, F), of the general linear group GL(n, F); that is

More generally, given a non-degenerate symmetric bilinear form or quadratic form[1] on a vector space over a field, the orthogonal group of the form is the group of invertible linear maps that preserve the form. The preceding orthogonal groups are the special case where, on some basis, the bilinear form is the dot product, or, equivalently, the quadratic form is the sum of the square of the coordinates.

All orthogonal groups are algebraic groups, since the condition of preserving a form can be expressed as an equality of matrices.

Name

[edit]The name of "orthogonal group" originates from the following characterization of its elements. Given a Euclidean vector space E of dimension n, the elements of the orthogonal group O(n) are, up to a uniform scaling (homothecy), the linear maps from E to E that map orthogonal vectors to orthogonal vectors.

In Euclidean geometry

[edit]The orthogonal O(n) is the subgroup of the general linear group GL(n, R), consisting of all endomorphisms that preserve the Euclidean norm; that is, endomorphisms g such that

Let E(n) be the group of the Euclidean isometries of a Euclidean space S of dimension n. This group does not depend on the choice of a particular space, since all Euclidean spaces of the same dimension are isomorphic. The stabilizer subgroup of a point x ∈ S is the subgroup of the elements g ∈ E(n) such that g(x) = x. This stabilizer is (or, more exactly, is isomorphic to) O(n), since the choice of a point as an origin induces an isomorphism between the Euclidean space and its associated Euclidean vector space.

There is a natural group homomorphism p from E(n) to O(n), which is defined by

where, as usual, the subtraction of two points denotes the translation vector that maps the second point to the first one. This is a well defined homomorphism, since a straightforward verification shows that, if two pairs of points have the same difference, the same is true for their images by g (for details, see Affine space § Subtraction and Weyl's axioms).

The kernel of p is the vector space of the translations. So, the translations form a normal subgroup of E(n), the stabilizers of two points are conjugate under the action of the translations, and all stabilizers are isomorphic to O(n).

Moreover, the Euclidean group is a semidirect product of O(n) and the group of translations. It follows that the study of the Euclidean group is essentially reduced to the study of O(n).

Special orthogonal group

[edit]By choosing an orthonormal basis of a Euclidean vector space, the orthogonal group can be identified with the group (under matrix multiplication) of orthogonal matrices, which are the matrices such that

It follows from this equation that the square of the determinant of Q equals 1, and thus the determinant of Q is either 1 or −1. The orthogonal matrices with determinant 1 form a subgroup called the special orthogonal group, denoted SO(n), consisting of all direct isometries of O(n), which are those that preserve the orientation of the space.

SO(n) is a normal subgroup of O(n), as being the kernel of the determinant, which is a group homomorphism whose image is the multiplicative group {−1, +1}. This implies that the orthogonal group is an internal semidirect product of SO(n) and any subgroup formed with the identity and a reflection.

The group with two elements {±I} (where I is the identity matrix) is a normal subgroup and even a characteristic subgroup of O(n), and, if n is even, also of SO(n). If n is odd, O(n) is the internal direct product of SO(n) and {±I}.

The group SO(2) is abelian (whereas SO(n) is not abelian when n > 2). Its finite subgroups are the cyclic group Ck of k-fold rotations, for every positive integer k. All these groups are normal subgroups of O(2) and SO(2).

Canonical form

[edit]For any element of O(n) there is an orthogonal basis, where its matrix has the form

where there may be any number, including zero, of ±1's; and where the matrices R1, ..., Rk are 2-by-2 rotation matrices, that is matrices of the form

with a2 + b2 = 1.

This results from the spectral theorem by regrouping eigenvalues that are complex conjugate, and taking into account that the absolute values of the eigenvalues of an orthogonal matrix are all equal to 1.

The element belongs to SO(n) if and only if there are an even number of −1 on the diagonal. A pair of eigenvalues −1 can be identified with a rotation by π and a pair of eigenvalues +1 can be identified with a rotation by 0.

The special case of n = 3 is known as Euler's rotation theorem, which asserts that every (non-identity) element of SO(3) is a rotation about a unique axis–angle pair.

Reflections

[edit]Reflections are the elements of O(n) whose canonical form is

where I is the (n − 1) × (n − 1) identity matrix, and the zeros denote row or column zero matrices. In other words, a reflection is a transformation that transforms the space in its mirror image with respect to a hyperplane.

In dimension two, every rotation can be decomposed into a product of two reflections. More precisely, a rotation of angle θ is the product of two reflections whose axes form an angle of θ / 2.

A product of up to n elementary reflections always suffices to generate any element of O(n). This results immediately from the above canonical form and the case of dimension two.

The Cartan–Dieudonné theorem is the generalization of this result to the orthogonal group of a nondegenerate quadratic form over a field of characteristic different from two.

The reflection through the origin (the map v ↦ −v) is an example of an element of O(n) that is not a product of fewer than n reflections.

Symmetry group of spheres

[edit]The orthogonal group O(n) is the symmetry group of the (n − 1)-sphere (for n = 3, this is just the sphere) and all objects with spherical symmetry, if the origin is chosen at the center.

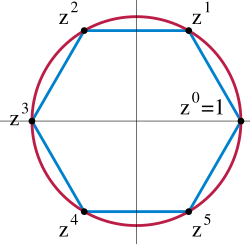

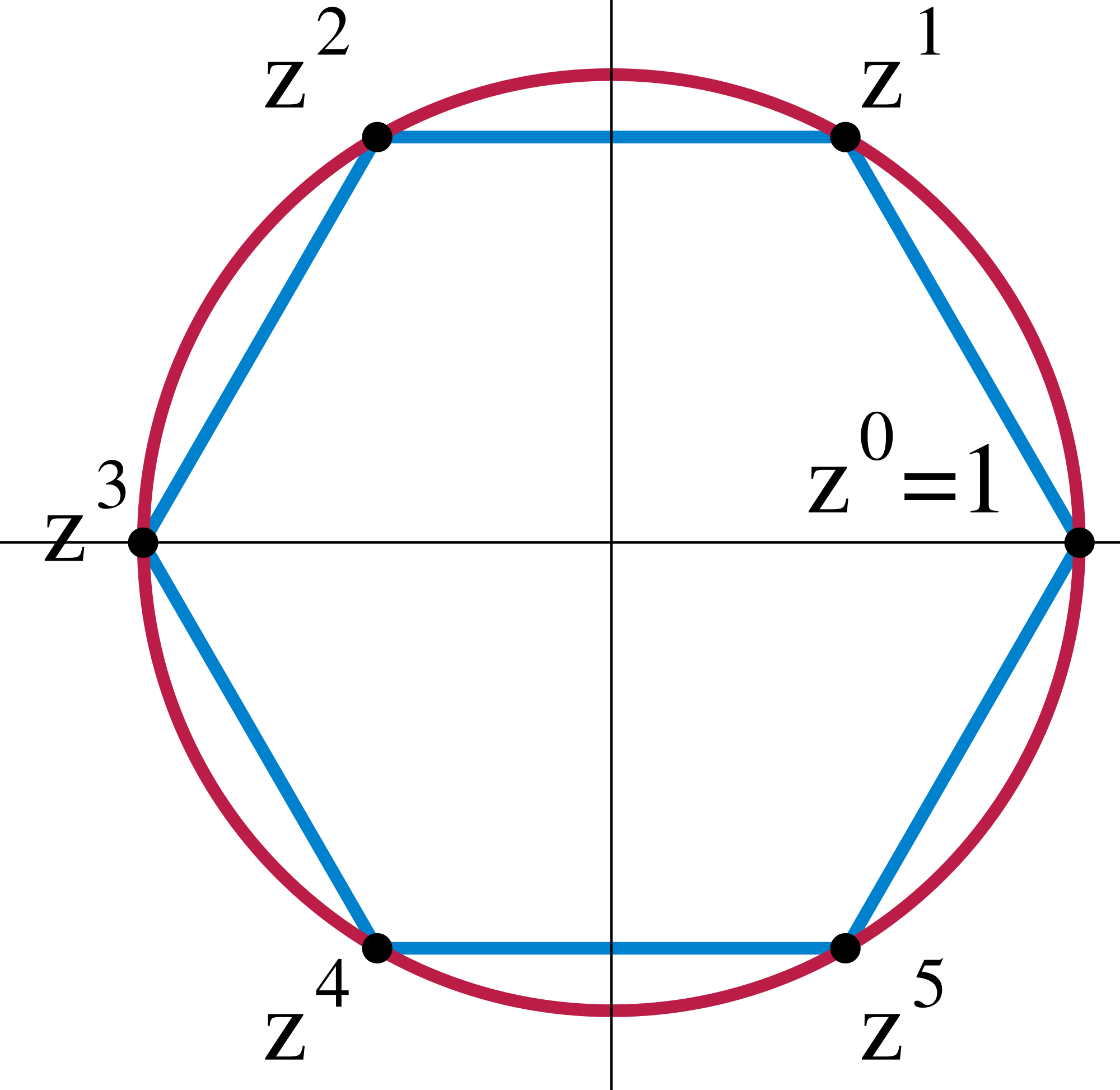

The symmetry group of a circle is O(2). The orientation-preserving subgroup SO(2) is isomorphic (as a real Lie group) to the circle group, also known as U(1), the multiplicative group of the complex numbers of absolute value equal to one. This isomorphism sends the complex number exp(φ i) = cos(φ) + i sin(φ) of absolute value 1 to the special orthogonal matrix

In higher dimension, O(n) has a more complicated structure (in particular, SO(n) is no longer commutative). The topological structures of the n-sphere and O(n) are strongly correlated, and this correlation is widely used for studying both topological spaces.

Group structure

[edit]The groups O(n) and SO(n) are real compact Lie groups of dimension n(n − 1) / 2. The group O(n) has two connected components, with SO(n) being the identity component, that is, the connected component containing the identity matrix.

As algebraic groups

[edit]The orthogonal group O(n) can be identified with the group of the matrices A such that ATA = I. Since both members of this equation are symmetric matrices, this provides n(n + 1) / 2 equations that the entries of an orthogonal matrix must satisfy, and which are not all satisfied by the entries of any non-orthogonal matrix.

This proves that O(n) is an algebraic set. Moreover, it can be proved[citation needed] that its dimension is

which implies that O(n) is a complete intersection. This implies that all its irreducible components have the same dimension, and that it has no embedded component. In fact, O(n) has two irreducible components, that are distinguished by the sign of the determinant (that is det(A) = 1 or det(A) = −1). Both are nonsingular algebraic varieties of the same dimension n(n − 1) / 2. The component with det(A) = 1 is SO(n).

Maximal tori and Weyl groups

[edit]A maximal torus in a compact Lie group G is a maximal subgroup among those that are isomorphic to Tk for some k, where T = SO(2) is the standard one-dimensional torus.[2]

In O(2n) and SO(2n), for every maximal torus, there is a basis on which the torus consists of the block-diagonal matrices of the form

where each Rj belongs to SO(2). In O(2n + 1) and SO(2n + 1), the maximal tori have the same form, bordered by a row and a column of zeros, and 1 on the diagonal.

The Weyl group of SO(2n + 1) is the semidirect product of a normal elementary abelian 2-subgroup and a symmetric group, where the nontrivial element of each {±1} factor of {±1}n acts on the corresponding circle factor of T × {1} by inversion, and the symmetric group Sn acts on both {±1}n and T × {1} by permuting factors. The elements of the Weyl group are represented by matrices in O(2n) × {±1}. The Sn factor is represented by block permutation matrices with 2-by-2 blocks, and a final 1 on the diagonal. The {±1}n component is represented by block-diagonal matrices with 2-by-2 blocks either

with the last component ±1 chosen to make the determinant 1.

The Weyl group of SO(2n) is the subgroup of that of SO(2n + 1), where Hn−1 < {±1}n is the kernel of the product homomorphism {±1}n → {±1} given by ; that is, Hn−1 < {±1}n is the subgroup with an even number of minus signs. The Weyl group of SO(2n) is represented in SO(2n) by the preimages under the standard injection SO(2n) → SO(2n + 1) of the representatives for the Weyl group of SO(2n + 1). Those matrices with an odd number of blocks have no remaining final −1 coordinate to make their determinants positive, and hence cannot be represented in SO(2n).

Topology

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, most notations are undefined; no context for explaining why these consideration belong to the article. Moreover, the section consists essentially in a list of advanced results without providing the information that is needed for a non-specialist for verifying them (no reference, no link to articles about the methods of computation that are used, no sketch of proofs. (November 2019) |

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (November 2019) |

Low-dimensional topology

[edit]The low-dimensional (real) orthogonal groups are familiar spaces:

- O(1) = S0, a two-point discrete space

- SO(1) = {1}

- SO(2) is S1

- SO(3) is RP3 [3]

- SO(4) is doubly covered by SU(2) × SU(2) = S3 × S3.

Fundamental group

[edit]In terms of algebraic topology, for n > 2 the fundamental group of SO(n, R) is cyclic of order 2,[4] and the spin group Spin(n) is its universal cover. For n = 2 the fundamental group is infinite cyclic and the universal cover corresponds to the real line (the group Spin(2) is the unique connected 2-fold cover).

Homotopy groups

[edit]Generally, the homotopy groups πk(O) of the real orthogonal group are related to homotopy groups of spheres, and thus are in general hard to compute. However, one can compute the homotopy groups of the stable orthogonal group (aka the infinite orthogonal group), defined as the direct limit of the sequence of inclusions:

Since the inclusions are all closed, hence cofibrations, this can also be interpreted as a union. On the other hand, Sn is a homogeneous space for O(n + 1), and one has the following fiber bundle:

which can be understood as "The orthogonal group O(n + 1) acts transitively on the unit sphere Sn, and the stabilizer of a point (thought of as a unit vector) is the orthogonal group of the perpendicular complement, which is an orthogonal group one dimension lower." Thus the natural inclusion O(n) → O(n + 1) is (n − 1)-connected, so the homotopy groups stabilize, and πk(O(n + 1)) = πk(O(n)) for n > k + 1: thus the homotopy groups of the stable space equal the lower homotopy groups of the unstable spaces.

From Bott periodicity we obtain Ω8O ≃ O, therefore the homotopy groups of O are 8-fold periodic, meaning πk + 8(O) = πk(O), and so one need list only the first 8 homotopy groups:

Relation to KO-theory

[edit]Via the clutching construction, homotopy groups of the stable space O are identified with stable vector bundles on spheres (up to isomorphism), with a dimension shift of 1: πk(O) = πk + 1(BO). Setting KO = BO × Z = Ω−1O × Z (to make π0 fit into the periodicity), one obtains:

Computation and interpretation of homotopy groups

[edit]Low-dimensional groups

[edit]The first few homotopy groups can be calculated by using the concrete descriptions of low-dimensional groups.

- π0(O) = π0(O(1)) = Z / 2Z, from orientation-preserving/reversing (this class survives to O(2) and hence stably)

- π1(O) = π1(SO(3)) = Z / 2Z, which is spin comes from SO(3) = RP3 = S3 / (Z / 2Z).

- π2(O) = π2(SO(3)) = 0, which surjects onto π2(SO(4)); this latter thus vanishes.

Lie groups

[edit]From general facts about Lie groups, π2(G) always vanishes, and π3(G) is free (free abelian).

Vector bundles

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (January 2024) |

π0(KO) is a vector bundle over S0, which consists of two points. Thus over each point, the bundle is trivial, and the non-triviality of the bundle is the difference between the dimensions of the vector spaces over the two points, so π0(KO) = Z is the dimension.

Loop spaces

[edit]Using concrete descriptions of the loop spaces in Bott periodicity, one can interpret the higher homotopies of O in terms of simpler-to-analyze homotopies of lower order. Using π0, O and O/U have two components, KO = BO × Z and KSp = BSp × Z have countably many components, and the rest are connected.

Interpretation of homotopy groups

[edit]In a nutshell:[5]

- π0(KO) = Z is about dimension

- π1(KO) = Z / 2Z is about orientation

- π2(KO) = Z / 2Z is about spin

- π4(KO) = Z is about topological quantum field theory.

Let R be any of the four division algebras R, C, H, O, and let LR be the tautological line bundle over the projective line RP1, and [LR] its class in K-theory. Noting that RP1 = S1, CP1 = S2, HP1 = S4, OP1 = S8, these yield vector bundles over the corresponding spheres, and

- π1(KO) is generated by [LR]

- π2(KO) is generated by [LC]

- π4(KO) is generated by [LH]

- π8(KO) is generated by [LO]

From the point of view of symplectic geometry, π0(KO) ≅ π8(KO) = Z can be interpreted as the Maslov index, thinking of it as the fundamental group π1(U/O) of the stable Lagrangian Grassmannian as U/O ≅ Ω7(KO), so π1(U/O) = π1+7(KO).

Whitehead tower

[edit]The orthogonal group anchors a Whitehead tower:

which is obtained by successively removing (killing) homotopy groups of increasing order. This is done by constructing short exact sequences starting with an Eilenberg–MacLane space for the homotopy group to be removed. The first few entries in the tower are the spin group and the string group, and are preceded by the fivebrane group. The homotopy groups that are killed are in turn π0(O) to obtain SO from O, π1(O) to obtain Spin from SO, π3(O) to obtain String from Spin, and then π7(O) and so on to obtain the higher order branes.

Of indefinite quadratic form over the reals

[edit]Over the real numbers, nondegenerate quadratic forms are classified by Sylvester's law of inertia, which asserts that, on a vector space of dimension n, such a form can be written as the difference of a sum of p squares and a sum of q squares, with p + q = n. In other words, there is a basis on which the matrix of the quadratic form is a diagonal matrix, with p entries equal to 1, and q entries equal to −1. The pair (p, q) called the inertia, is an invariant of the quadratic form, in the sense that it does not depend on the way of computing the diagonal matrix.

The orthogonal group of a quadratic form depends only on the inertia, and is thus generally denoted O(p, q). Moreover, as a quadratic form and its opposite have the same orthogonal group, one has O(p, q) = O(q, p).

The standard orthogonal group is O(n) = O(n, 0) = O(0, n). So, in the remainder of this section, it is supposed that neither p nor q is zero.

The subgroup of the matrices of determinant 1 in O(p, q) is denoted SO(p, q). The group O(p, q) has four connected components, depending on whether an element preserves orientation on either of the two maximal subspaces where the quadratic form is positive definite or negative definite. The component of the identity, whose elements preserve orientation on both subspaces, is denoted SO+(p, q).

The group O(3, 1) is the Lorentz group that is fundamental in relativity theory. Here the 3 corresponds to space coordinates, and 1 corresponds to the time coordinate.

Of complex quadratic forms

[edit]Over the field C of complex numbers, every non-degenerate quadratic form in n variables is equivalent to x12 + ... + xn2. Thus, up to isomorphism, there is only one non-degenerate complex quadratic space of dimension n, and one associated orthogonal group, usually denoted O(n, C). It is the group of complex orthogonal matrices, complex matrices whose product with their transpose is the identity matrix.

As in the real case, O(n, C) has two connected components. The component of the identity consists of all matrices of determinant 1 in O(n, C); it is denoted SO(n, C).

The groups O(n, C) and SO(n, C) are complex Lie groups of dimension n(n − 1) / 2 over C (the dimension over R is twice that). For n ≥ 2, these groups are noncompact. As in the real case, SO(n, C) is not simply connected: For n > 2, the fundamental group of SO(n, C) is cyclic of order 2, whereas the fundamental group of SO(2, C) is Z.

Over finite fields

[edit]Characteristic different from two

[edit]Over a field of characteristic different from two, two quadratic forms are equivalent if their matrices are congruent, that is if a change of basis transforms the matrix of the first form into the matrix of the second form. Two equivalent quadratic forms have clearly the same orthogonal group.

The non-degenerate quadratic forms over a finite field of characteristic different from two are completely classified into congruence classes, and it results from this classification that there is only one orthogonal group in odd dimension and two in even dimension.

More precisely, Witt's decomposition theorem asserts that (in characteristic different from two) every vector space equipped with a non-degenerate quadratic form Q can be decomposed as a direct sum of pairwise orthogonal subspaces

where each Li is a hyperbolic plane (that is there is a basis such that the matrix of the restriction of Q to Li has the form ), and the restriction of Q to W is anisotropic (that is, Q(w) ≠ 0 for every nonzero w in W).

The Chevalley–Warning theorem asserts that, over a finite field, the dimension of W is at most two.

If the dimension of V is odd, the dimension of W is thus equal to one, and its matrix is congruent either to or to where 𝜑 is a non-square scalar. It results that there is only one orthogonal group that is denoted O(2n + 1, q), where q is the number of elements of the finite field (a power of an odd prime).[6]

If the dimension of W is two and −1 is not a square in the ground field (that is, if its number of elements q is congruent to 3 modulo 4), the matrix of the restriction of Q to W is congruent to either I or −I, where I is the 2×2 identity matrix. If the dimension of W is two and −1 is a square in the ground field (that is, if q is congruent to 1, modulo 4) the matrix of the restriction of Q to W is congruent to φ is any non-square scalar.

This implies that if the dimension of V is even, there are only two orthogonal groups, depending whether the dimension of W zero or two. They are denoted respectively O+(2n, q) and O−(2n, q).[6]

The orthogonal group Oε(2, q) is a dihedral group of order 2(q − ε), where ε = ±.

For studying the orthogonal group of Oε(2, q), one can suppose that the matrix of the quadratic form is because, given a quadratic form, there is a basis where its matrix is diagonalizable. A matrix belongs to the orthogonal group if AQAT = Q, that is, a2 − ωb2 = 1, ac − ωbd = 0, and c2 − ωd2 = −ω. As a and b cannot be both zero (because of the first equation), the second equation implies the existence of ε in Fq, such that c = εωb and d = εa. Reporting these values in the third equation, and using the first equation, one gets that ε2 = 1, and thus the orthogonal group consists of the matrices

where a2 − ωb2 = 1 and ε = ±1. Moreover, the determinant of the matrix is ε.

For further studying the orthogonal group, it is convenient to introduce a square root α of ω. This square root belongs to Fq if the orthogonal group is O+(2, q), and to Fq2 otherwise. Setting x = a + αb, and y = a − αb, one has

If and are two matrices of determinant one in the orthogonal group then

This is an orthogonal matrix with a = a1a2 + ωb1b2, and b = a1b2 + b1a2. Thus

It follows that the map (a, b) ↦ a + αb is a homomorphism of the group of orthogonal matrices of determinant one into the multiplicative group of Fq2.

In the case of O+(2n, q), the image is the multiplicative group of Fq, which is a cyclic group of order q.

In the case of O–(2n, q), the above x and y are conjugate, and are therefore the image of each other by the Frobenius automorphism. This meant that and thus xq+1 = 1. For every such x one can reconstruct a corresponding orthogonal matrix. It follows that the map is a group isomorphism from the orthogonal matrices of determinant 1 to the group of the (q + 1)-roots of unity. This group is a cyclic group of order q + 1 which consists of the powers of gq−1, where g is a primitive element of Fq2,

For finishing the proof, it suffices to verify that the group all orthogonal matrices is not abelian, and is the semidirect product of the group {1, −1} and the group of orthogonal matrices of determinant one.

The comparison of this proof with the real case may be illuminating.

Here two group isomorphisms are involved:

where g is a primitive element of Fq2 and T is the multiplicative group of the element of norm one in Fq2 ;

with and

In the real case, the corresponding isomorphisms are:

where C is the circle of the complex numbers of norm one;

with and

When the characteristic is not two, the order of the orthogonal groups are[7]

In characteristic two, the formulas are the same, except that the factor 2 of |O(2n + 1, q)| must be removed.

Dickson invariant

[edit]For orthogonal groups, the Dickson invariant is a homomorphism from the orthogonal group to the quotient group Z / 2Z (integers modulo 2), taking the value 0 in case the element is the product of an even number of reflections, and the value of 1 otherwise.[8]

Algebraically, the Dickson invariant can be defined as D(f) = rank(I − f) modulo 2, where I is the identity (Taylor 1992, Theorem 11.43). Over fields that are not of characteristic 2 it is equivalent to the determinant: the determinant is −1 to the power of the Dickson invariant. Over fields of characteristic 2, the determinant is always 1, so the Dickson invariant gives more information than the determinant.

The special orthogonal group is the kernel of the Dickson invariant[8] and usually has index 2 in O(n, F ).[9] When the characteristic of F is not 2, the Dickson Invariant is 0 whenever the determinant is 1. Thus when the characteristic is not 2, SO(n, F ) is commonly defined to be the elements of O(n, F ) with determinant 1. Each element in O(n, F ) has determinant ±1. Thus in characteristic 2, the determinant is always 1.

The Dickson invariant can also be defined for Clifford groups and pin groups in a similar way (in all dimensions).

Orthogonal groups of characteristic 2

[edit]Over fields of characteristic 2 orthogonal groups often exhibit special behaviors, some of which are listed in this section. (Formerly these groups were known as the hypoabelian groups, but this term is no longer used.)

- Any orthogonal group over any field is generated by reflections, except for a unique example where the vector space is 4-dimensional over the field with 2 elements and the Witt index is 2.[10] A reflection in characteristic two has a slightly different definition. In characteristic two, the reflection orthogonal to a vector u takes a vector v to v + B(v, u)/Q(u) · u where B is the bilinear form[clarification needed] and Q is the quadratic form associated to the orthogonal geometry. Compare this to the Householder reflection of odd characteristic or characteristic zero, which takes v to v − 2·B(v, u)/Q(u) · u.

- The center of the orthogonal group usually has order 1 in characteristic 2, rather than 2, since I = −I.

- In odd dimensions 2n + 1 in characteristic 2, orthogonal groups over perfect fields are the same as symplectic groups in dimension 2n. In fact the symmetric form is alternating in characteristic 2, and as the dimension is odd it must have a kernel of dimension 1, and the quotient by this kernel is a symplectic space of dimension 2n, acted upon by the orthogonal group.

- In even dimensions in characteristic 2 the orthogonal group is a subgroup of the symplectic group, because the symmetric bilinear form of the quadratic form is also an alternating form.

The spinor norm

[edit]The spinor norm is a homomorphism from an orthogonal group over a field F to the quotient group F× / (F×)2 (the multiplicative group of the field F up to multiplication by square elements), that takes reflection in a vector of norm n to the image of n in F× / (F×)2.[11]

For the usual orthogonal group over the reals, it is trivial, but it is often non-trivial over other fields, or for the orthogonal group of a quadratic form over the reals that is not positive definite.

Galois cohomology and orthogonal groups

[edit]In the theory of Galois cohomology of algebraic groups, some further points of view are introduced. They have explanatory value, in particular in relation with the theory of quadratic forms; but were for the most part post hoc, as far as the discovery of the phenomenon is concerned. The first point is that quadratic forms over a field can be identified as a Galois H1, or twisted forms (torsors) of an orthogonal group. As an algebraic group, an orthogonal group is in general neither connected nor simply-connected; the latter point brings in the spin phenomena, while the former is related to the determinant.

The 'spin' name of the spinor norm can be explained by a connection to the spin group (more accurately a pin group). This may now be explained quickly by Galois cohomology (which however postdates the introduction of the term by more direct use of Clifford algebras). The spin covering of the orthogonal group provides a short exact sequence of algebraic groups.

Here μ2 is the algebraic group of square roots of 1; over a field of characteristic not 2 it is roughly the same as a two-element group with trivial Galois action. The connecting homomorphism from H0(OV), which is simply the group OV(F) of F-valued points, to H1(μ2) is essentially the spinor norm, because H1(μ2) is isomorphic to the multiplicative group of the field modulo squares.

There is also the connecting homomorphism from H1 of the orthogonal group, to the H2 of the kernel of the spin covering. The cohomology is non-abelian so that this is as far as we can go, at least with the conventional definitions.

Lie algebra

[edit]The Lie algebra corresponding to Lie groups O(n, F ) and SO(n, F ) consists of the skew-symmetric n × n matrices, with the Lie bracket [ , ] given by the commutator. One Lie algebra corresponds to both groups. It is often denoted by or , and called the orthogonal Lie algebra or special orthogonal Lie algebra. Over real numbers, these Lie algebras for different n are the compact real forms of two of the four families of semisimple Lie algebras: in odd dimension Bk, where n = 2k + 1, while in even dimension Dr, where n = 2r.

Since the group SO(n) is not simply connected, the representation theory of the orthogonal Lie algebras includes both representations corresponding to ordinary representations of the orthogonal groups, and representations corresponding to projective representations of the orthogonal groups. (The projective representations of SO(n) are just linear representations of the universal cover, the spin group Spin(n).) The latter are the so-called spin representation, which are important in physics.

More generally, given a vector space V (over a field with characteristic not equal to 2) with a nondegenerate symmetric bilinear form , the special orthogonal Lie algebra consists of tracefree endomorphisms which are skew-symmetric for this form (). Over a field of characteristic 2 we consider instead the alternating endomorphisms. Concretely we can equate these with the bivectors of the exterior algebra, the antisymmetric tensors of . The correspondence is given by:

This description applies equally for the indefinite special orthogonal Lie algebras for symmetric bilinear forms with signature (p, q).

Over real numbers, this characterization is used in interpreting the curl of a vector field (naturally a bivector) as an infinitesimal rotation or "curl", hence the name.

Related groups

[edit]The orthogonal groups and special orthogonal groups have a number of important subgroups, supergroups, quotient groups, and covering groups. These are listed below.

The inclusions O(n) ⊂ U(n) ⊂ USp(2n) and USp(n) ⊂ U(n) ⊂ O(2n) are part of a sequence of 8 inclusions used in a geometric proof of the Bott periodicity theorem, and the corresponding quotient spaces are symmetric spaces of independent interest – for example, U(n)/O(n) is the Lagrangian Grassmannian.

Lie subgroups

[edit]In physics, particularly in the areas of Kaluza–Klein compactification, it is important to find out the subgroups of the orthogonal group. The main ones are:

- – preserve an axis

- – U(n) are those that preserve a compatible complex structure or a compatible symplectic structure – see 2-out-of-3 property; SU(n) also preserves a complex orientation.

Lie supergroups

[edit]The orthogonal group O(n) is also an important subgroup of various Lie groups:

Conformal group

[edit]Being isometries, real orthogonal transforms preserve angles, and are thus conformal maps, though not all conformal linear transforms are orthogonal. In classical terms this is the difference between congruence and similarity, as exemplified by SSS (side-side-side) congruence of triangles and AAA (angle-angle-angle) similarity of triangles. The group of conformal linear maps of Rn is denoted CO(n) for the conformal orthogonal group, and consists of the product of the orthogonal group with the group of dilations. If n is odd, these two subgroups do not intersect, and they are a direct product: CO(2k + 1) = O(2k + 1) × R∗, where R∗ = R∖{0} is the real multiplicative group, while if n is even, these subgroups intersect in ±1, so this is not a direct product, but it is a direct product with the subgroup of dilation by a positive scalar: CO(2k) = O(2k) × R+.

Similarly one can define CSO(n); this is always: CSO(n) = CO(n) ∩ GL+(n) = SO(n) × R+.

Discrete subgroups

[edit]As the orthogonal group is compact, discrete subgroups are equivalent to finite subgroups.[note 1] These subgroups are known as point groups and can be realized as the symmetry groups of polytopes. A very important class of examples are the finite Coxeter groups, which include the symmetry groups of regular polytopes.

Dimension 3 is particularly studied – see point groups in three dimensions, polyhedral groups, and list of spherical symmetry groups. In 2 dimensions, the finite groups are either cyclic or dihedral – see point groups in two dimensions.

Other finite subgroups include:

- Permutation matrices (the Coxeter group An)

- Signed permutation matrices (the Coxeter group Bn); also equals the intersection of the orthogonal group with the integer matrices.[note 2]

Covering and quotient groups

[edit]The orthogonal group is neither simply connected nor centerless, and thus has both a covering group and a quotient group, respectively:

- Two covering Pin groups, Pin+(n) → O(n) and Pin−(n) → O(n),

- The quotient projective orthogonal group, O(n) → PO(n).

These are all 2-to-1 covers.

For the special orthogonal group, the corresponding groups are:

- Spin group, Spin(n) → SO(n),

- Projective special orthogonal group, SO(n) → PSO(n).

Spin is a 2-to-1 cover, while in even dimension, PSO(2k) is a 2-to-1 cover, and in odd dimension PSO(2k + 1) is a 1-to-1 cover; i.e., isomorphic to SO(2k + 1). These groups, Spin(n), SO(n), and PSO(n) are Lie group forms of the compact special orthogonal Lie algebra, – Spin is the simply connected form, while PSO is the centerless form, and SO is in general neither.[note 3]

In dimension 3 and above these are the covers and quotients, while dimension 2 and below are somewhat degenerate; see specific articles for details.

Principal homogeneous space: Stiefel manifold

[edit]The principal homogeneous space for the orthogonal group O(n) is the Stiefel manifold Vn(Rn) of orthonormal bases (orthonormal n-frames).

In other words, the space of orthonormal bases is like the orthogonal group, but without a choice of base point: given an orthogonal space, there is no natural choice of orthonormal basis, but once one is given one, there is a one-to-one correspondence between bases and the orthogonal group. Concretely, a linear map is determined by where it sends a basis: just as an invertible map can take any basis to any other basis, an orthogonal map can take any orthogonal basis to any other orthogonal basis.

The other Stiefel manifolds Vk(Rn) for k < n of incomplete orthonormal bases (orthonormal k-frames) are still homogeneous spaces for the orthogonal group, but not principal homogeneous spaces: any k-frame can be taken to any other k-frame by an orthogonal map, but this map is not uniquely determined.

See also

[edit]Specific transforms

[edit]Specific groups

[edit]Related groups

[edit]Lists of groups

[edit]Representation theory

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Infinite subsets of a compact space have an accumulation point and are not discrete.

- ^ O(n) ∩ GL(n, Z) equals the signed permutation matrices because an integer vector of norm 1 must have a single non-zero entry, which must be ±1 (if it has two non-zero entries or a larger entry, the norm will be larger than 1), and in an orthogonal matrix these entries must be in different coordinates, which is exactly the signed permutation matrices.

- ^ In odd dimension, SO(2k + 1) ≅ PSO(2k + 1) is centerless (but not simply connected), while in even dimension SO(2k) is neither centerless nor simply connected.

Citations

[edit]- ^ For base fields of characteristic not 2, the definition in terms of a symmetric bilinear form is equivalent to that in terms of a quadratic form, but in characteristic 2 these notions differ.

- ^ Hall 2015 Theorem 11.2

- ^ Hall 2015 Section 1.3.4

- ^ Hall 2015 Proposition 13.10

- ^ Baez, John. "Week 105". This Week's Finds in Mathematical Physics. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ a b Wilson, Robert A. (2009). The finite simple groups. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 251. London: Springer. pp. 69–75. ISBN 978-1-84800-987-5. Zbl 1203.20012.

- ^ (Taylor 1992, p. 141)

- ^ a b Knus, Max-Albert (1991), Quadratic and Hermitian forms over rings, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, vol. 294, Berlin etc.: Springer-Verlag, p. 224, ISBN 3-540-52117-8, Zbl 0756.11008

- ^ (Taylor 1992, page 160)

- ^ (Grove 2002, Theorem 6.6 and 14.16)

- ^ Cassels 1978, p. 178

References

[edit]- Cassels, J.W.S. (1978), Rational Quadratic Forms, London Mathematical Society Monographs, vol. 13, Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-163260-1, Zbl 0395.10029

- Grove, Larry C. (2002), Classical groups and geometric algebra, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, vol. 39, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-2019-3, MR 1859189

- Hall, Brian C. (2015), Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 222 (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-3319134666

- Taylor, Donald E. (1992), The Geometry of the Classical Groups, Sigma Series in Pure Mathematics, vol. 9, Berlin: Heldermann Verlag, ISBN 3-88538-009-9, MR 1189139, Zbl 0767.20001

External links

[edit]Orthogonal group

View on GrokipediaDefinition

Notation and naming

The orthogonal group in -dimensional Euclidean space, denoted , comprises all linear transformations that preserve the standard dot product on .[9] This notation emphasizes the group's role in maintaining orthogonality among vectors under the Euclidean metric.[10] The subgroup consisting of those elements with determinant equal to 1 is known as the special orthogonal group, denoted .[9] The naming convention arises from the transformations' preservation of angles and lengths, a direct consequence of conserving the dot product, which generalizes the geometric notion of perpendicularity.[11] The term "orthogonal" originates from the Greek roots orthos (straight or right) and gonia (angle), literally meaning "right-angled," reflecting the preservation of right angles between vectors.[12] Charles Hermite introduced the phrase "orthogonal matrix" in 1854 to describe such transformations in his work on quadratic forms.[13] For spaces equipped with an indefinite quadratic form of signature , where , the analogous group is denoted , adapting the notation to the non-Euclidean metric.[11] This variation highlights the flexibility of the framework beyond positive-definite cases.[14]Basic definition

In mathematics, the orthogonal group associated to a vector space over a field equipped with a non-degenerate quadratic form is defined as the group consisting of all invertible linear transformations such that for every .[15] This condition ensures that preserves the quadratic form , making the full group of isometries of the quadratic space .[15] Equivalently, these transformations are the automorphisms of that preserve the associated symmetric bilinear form , assuming .[16] Over the real numbers , when is equipped with the standard positive definite quadratic form , the orthogonal group (often denoted simply ) consists of all real matrices satisfying , where is the identity matrix.[9] Every such matrix has determinant , since implies .[9] More generally, over any field (with ), if is the Gram matrix representing the symmetric bilinear form with respect to a basis of , then the elements of the orthogonal group are the matrices satisfying .[16] This matrix equation captures the preservation of the quadratic form in coordinates.[16] Over , is a smooth manifold of dimension . To show this, define the map by , where is the space of symmetric real matrices. Then . The derivative is ; this follows from the definition , as the term vanishes in the limit. At , this is surjective onto symmetric matrices. To see surjectivity, since is orthogonal, , take . Then . Thus, is a regular value. By the regular value theorem,[17] is a smooth submanifold of dimension .[18][19] More generally, over , if is a non-degenerate symmetric matrix, the group is a smooth manifold of dimension . The proof is analogous, with the map and differential . At , surjectivity onto follows by choosing, for symmetric , . To verify, from it follows that ; then , where , so (since , obtained by inverting ), and thus . Since is symmetric and is symmetric, the second term , yielding . Examples include the indefinite orthogonal groups with , such as the Lorentz group . Moreover, is compact. The condition implies the rows (and columns) of are orthonormal, so the Frobenius norm satisfies , bounding in . As the preimage of the closed set under the continuous map , is closed. By the Heine-Borel theorem, is compact.[19]Geometric interpretation

Euclidean geometry

The orthogonal group is the group of all linear isometries of the Euclidean space that fix the origin, consisting of transformations that preserve distances and angles between vectors.[20] These isometries derive their preserving properties from maintaining the standard quadratic form , ensuring and for all .[16] As referenced in the basic definition, elements satisfy , which directly implies norm preservation.[21] The group splits into orientation-preserving and orientation-reversing isometries, with the former forming the connected component of rotations and the latter comprising the "odd" elements with determinant , such as reflections.[22] Rotations constitute the identity-connected component of , while reflections and their compositions with rotations reverse orientation.[23] In two dimensions, is generated by rotations about the origin and a single reflection, such as over the x-axis, yielding all orientation-preserving and -reversing linear isometries fixing the origin.[24] For instance, the reflection matrix combined with rotation matrices produces the full group. In three dimensions, includes rotations around any axis through the origin as well as improper rotations, which combine a proper rotation with a reflection (or equivalently, with central inversion).[25] These improper elements, like a 180-degree rotation followed by reflection in a plane perpendicular to the axis, account for all orientation-reversing isometries in .[26]Special orthogonal group

The special orthogonal group, denoted SO(), is defined as the subgroup of the orthogonal group O() consisting of all real orthogonal matrices satisfying , that is, [27] This makes SO() the kernel of the surjective determinant homomorphism , establishing SO() as a normal subgroup of index 2 in O().[3] For , SO() coincides with the connected component of the identity element in O(), capturing all orientation-preserving orthogonal transformations.[3] As a matrix Lie group, SO() inherits a smooth manifold structure from O(), with the same Lie algebra consisting of skew-symmetric matrices.[28] The dimension of this Lie group is , reflecting the degrees of freedom in specifying rotations while preserving orthogonality and determinant 1.[29] A prominent example is SO(3), which parameterizes all proper rotations in three-dimensional Euclidean space. Elements of SO(3) can be represented via the axis-angle parameterization, where each rotation is specified by a unit vector (the rotation axis) and an angle (the rotation amount), according to Euler's rotation theorem.[30] Alternatively, Euler angles provide a parameterization using three angles , corresponding to successive rotations about coordinate axes (e.g., Z-Y-X convention: rotation by about z, then about y, then about x).[31] SO() is doubly covered by the spin group Spin(), a simply connected Lie group that projects onto SO() via a 2-to-1 homomorphism with kernel .[32]Reflections and canonical forms

Householder reflections provide a fundamental means of constructing elements of the orthogonal group . A Householder reflection is an orthogonal transformation defined by a unit vector with , given by the matrix where is the identity matrix and denotes the transpose of . This matrix represents a reflection across the hyperplane orthogonal to , fixing all vectors in that hyperplane while mapping to .[33] The eigenvalues of a Householder reflection matrix consist of with multiplicity and with multiplicity , reflecting its geometric action: it leaves an -dimensional subspace unchanged (eigenvalue ) and reverses the direction along the normal vector (eigenvalue ). This spectral structure underscores the reflection's determinant of and its role as an improper orthogonal transformation.[34] The full orthogonal group over the reals, for , is generated by such reflections. Any orthogonal matrix can be expressed as a product of Householder reflections, a property rooted in the fact that reflections form a generating set for the group, allowing decomposition into basic geometric operations. This generation extends to the infinite Coxeter group structure associated with the root system of type , where reflections correspond to the Weyl group generators.[35] A key application of Householder reflections lies in the canonical forms of quadratic forms under orthogonal transformations, as described by Sylvester's law of inertia. For a real symmetric bilinear form defined by a matrix , there exists an orthogonal matrix such that , where is a diagonal matrix with entries (say, times), (say, times), and (say, times), with . The triple is the inertia of the form and remains invariant under all orthogonal changes of basis, classifying quadratic forms up to orthogonal equivalence. This diagonalization highlights the orthogonal group's ability to preserve the signature while simplifying the form.[36] In numerical algorithms, Householder reflections enable the QR decomposition of a full-rank matrix (with ) as , where (or more precisely, in the Stiefel manifold) and is upper triangular. The process applies a sequence of Householder transformations to introduce zeros below the diagonal in successive columns of , yielding and . Each is chosen to reflect the -th column subvector onto a multiple of the standard basis vector, ensuring numerical stability and efficiency in applications like solving least squares problems.[37]Symmetry of spheres

The orthogonal group acts on the unit sphere in via the natural linear action for and . This action preserves the sphere because orthogonal matrices satisfy , implying for all , and thus map unit vectors to unit vectors.[38] The special orthogonal group , consisting of the determinant-1 elements of , forms the connected component of rotations that act as orientation-preserving isometries on . This subgroup acts transitively on for , meaning that for any two points , there exists such that . The stabilizer of a fixed point, such as the standard basis vector , is isomorphic to , which acts on the orthogonal hyperplane . Consequently, is diffeomorphic to the homogeneous space .[38][39] The full group extends this action to include orientation-reversing isometries, such as reflections. In particular, the central inversion realizes the antipodal map , which preserves the sphere and pairs antipodal points. While the isometry group of the round embedded in is precisely , the focus here is on this linear orthogonal action rather than the broader isometry group of in , which is .[3][38] A concrete example arises for , where parametrizes the rotations of the 2-sphere , corresponding to the symmetry group of a sphere in three-dimensional space, such as in rigid body dynamics or spherical geometry. Any orientation-preserving isometry of is a rotation around some axis through the origin.[40]Algebraic structure

Matrix groups over fields

The orthogonal group over a field of characteristic not 2 is defined as the subgroup of the general linear group consisting of all matrices with entries in such that , where is the transpose of and is the identity matrix. This condition ensures that preserves the standard bilinear form on the vector space , making the group of linear isometries with respect to this form. The assumption on the characteristic avoids complications with the definition of the transpose and symmetric forms, as in characteristic 2 the theory requires separate treatment using alternating forms.[41] Explicit examples of elements in can be constructed over specific fields like the rationals or finite fields with odd. Over , a simple rotation matrix in is given by which has order 4 and satisfies the defining relation.[3] Over for odd prime , diagonal matrices with entries on the diagonal form reflections or sign changes that belong to the group, such as the matrix with a single -1 and the rest 1's, preserving the form.[42] These examples illustrate how the group structure manifests in low dimensions over fields with explicit arithmetic. The orthogonal group acts on the space of quadratic forms over via the adjoint action: for a quadratic form associated to a symmetric matrix , the action of is , yielding the transformed form with matrix .[43] Since , this action preserves the standard form (where ), and more generally, it acts on the set of non-degenerate quadratic forms by congruence, classifying them up to isomorphism under the field's properties.[44] Elements of finite order in generate cyclic subgroups, which are crucial for understanding the group's torsion. For instance, over fields containing roots of unity, rotations by angles corresponding to roots of cyclotomic polynomials yield elements of order dividing the field's multiplicative order; over , such elements are limited to orders 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 due to the possible rotation angles in rational matrices.[45] These cyclic subgroups embed into tori within the group, but their explicit matrix forms highlight the discrete symmetries preserved by the orthogonal condition. Unlike the unitary group over the complex numbers , where matrices satisfy with the conjugate transpose, the orthogonal group over uses only the transpose, ignoring complex conjugation.[46] This distinction means is not a subgroup of the unitary group , as orthogonal matrices need not preserve the Hermitian form, leading to different topological and algebraic behaviors over .[47]Algebraic groups

Over an algebraically closed field of characteristic not equal to 2, the orthogonal group is defined as the closed subgroup of the general linear group consisting of matrices satisfying , where denotes the transpose of and is the identity matrix. This set of equations defines a smooth affine variety, thereby endowing with the structure of a linear algebraic group. The special orthogonal group is the kernel of the determinant homomorphism , which identifies it as the connected component of the identity in .[48] Both and are reductive linear algebraic groups, meaning their unipotent radicals are trivial and they admit a Levi decomposition for every parabolic subgroup.[48] For , is in fact semisimple, with finite center and no nontrivial abelian normal subgroups.[48] Reductive groups like these possess a well-developed theory of subgroups, including Borel subgroups, which are maximal connected solvable subgroups, and parabolic subgroups, which contain a Borel subgroup and admit a semidirect product decomposition into a Levi factor and a unipotent radical.[49] In the case of the orthogonal group, a standard Borel subgroup stabilizes a complete flag of subspaces isotropic with respect to the underlying nondegenerate symmetric bilinear form, while parabolic subgroups correspond to partial such flags and preserve the induced form on quotients.[49] The classification of these groups as semisimple algebraic groups relies on their associated root systems and corresponding Dynkin diagrams. For the odd-dimensional special orthogonal group , the root system is of type , with Dynkin diagram comprising nodes connected by edges: the first edges are single bonds, and the final edge is a double bond with an arrow indicating the shorter root.[50] For the even-dimensional case , the root system is of type , whose Dynkin diagram features nodes with single bonds connecting the first pairs, followed by the -th node linked by single bonds to two terminal nodes.[50] These diagrams encode the relations among simple roots and underpin the structure theory, including the Weyl group and representation theory of the groups.[50] Over the complex numbers , an algebraically closed field, the orthogonal group is split reductive, admitting a maximal torus that splits completely over (isomorphic to where is the rank).[51] In contrast, over the reals , the standard orthogonal group preserving the positive definite quadratic form is a compact real form of the complex group and lacks a split maximal torus, corresponding to a non-split real structure.[51] Split real forms of the orthogonal group arise instead from indefinite quadratic forms, such as with and , where a split torus exists when the signature allows a suitable choice of Cartan subalgebra.[51]Maximal tori and Weyl groups

In the special orthogonal group , a maximal torus consists of block-diagonal matrices formed by copies of rotation matrices for , embedded along the diagonal. This subgroup is maximal abelian and connected, isomorphic to the -torus . Similarly, in , a maximal torus is obtained by adjoining a identity block to the structure in , yielding an embedding of into the odd-dimensional group. The Weyl group of the orthogonal group is defined as the quotient , where is the normalizer of in . For or , is isomorphic to the hyperoctahedral group of rank , which consists of all signed permutations of elements and has order ; this group can be realized as the subgroup of generated by permutations and diagonal sign changes.[52] For with , the Weyl group is the index-2 subgroup of the hyperoctahedral group comprising signed permutations with an even number of sign changes.[52] The Weyl group acts on the maximal torus by conjugation: elements of conjugate elements of , and since is abelian, this descends to a well-defined action of on . Identifying with via the angles , the action corresponds to permuting the coordinates and replacing with (reflecting across the corresponding root hyperplane).[53] This action is faithful and reflects the symmetry of the root system. The root system associated to is of type , with simple roots in the standard Euclidean space (where are the basis vectors); the full roots are () and .[52] For , the root system is of type , with simple roots ; the roots are () excluding the short roots.[52] The Weyl group is generated by reflections across the hyperplanes orthogonal to these roots. The length function on the Weyl group counts the minimal number of simple reflections needed to express , equivalent to the number of inversions in the permutation part plus the number of negative signs for type . The Bruhat order on is the partial order generated by covering relations where for simple roots , providing a combinatorial structure for decomposing elements and cells in the flag variety.[54]Topology

Low-dimensional cases

The orthogonal group over the reals consists of the orthogonal matrices, which are precisely the elements , forming a discrete group isomorphic to .[9] This group is trivial in the sense that it has only two elements and acts on the real line by preservation of the absolute value.[9] In dimension 2, the orthogonal group is the group of isometries of the Euclidean plane preserving orientation up to reflection, and it is isomorphic to the infinite dihedral group .[55] This structure arises as the semidirect product , where the infinite cyclic subgroup corresponds to rotations and the factor to reflections.[55] The special orthogonal subgroup consists solely of rotations and is isomorphic to the circle group , the multiplicative group of complex numbers of modulus 1, or topologically to the 1-sphere ./01%3A_Chapters/12%3A_The_Circle_Group) Explicitly, the isomorphism maps to the rotation matrix ./01%3A_Chapters/12%3A_The_Circle_Group) For dimension 3, the special orthogonal group is the group of rotations of , which admits a double cover by the special unitary group , the group of unitary matrices with determinant 1.[56] This covering map is a 2-to-1 homomorphism with kernel , reflecting that rotations by an angle and are identified in but distinct in .[57] Topologically, is homeomorphic to the real projective space , obtained as the quotient of the 3-sphere by the antipodal map, and its fundamental group is , indicating it is not simply connected.[56][58] Furthermore, is isomorphic to the projective special unitary group , providing an identification with projective transformations preserving the Hermitian form on .[59] The finite subgroups of include the alternating group (icosahedral rotations), whose double cover in is the binary icosahedral group of order 120, yielding quotients like the Poincaré homology sphere binary icosahedral.[60]Fundamental group

The special orthogonal group is path-connected for all . Its fundamental group is since is diffeomorphic to the circle , and for .[61] The orthogonal group consists of two path-connected components for , corresponding to matrices with determinant (namely ) and determinant . These components are diffeomorphic via multiplication by a fixed reflection matrix, so in each case. For , both and are discrete (the trivial group and , respectively), yielding trivial fundamental groups.[62] To establish , consider the determinant fibration with fiber . The long exact sequence of homotopy groups for this fibration is The relevant portion for shows that the induced map is an isomorphism, while the portion for confirms the two components of .[63][62] The group for arises as the deck transformation group of the universal covering space of , given by the spin group , which is a double cover (i.e., 2-to-1). For , the analogous covering given by is infinite, consistent with . For , is diffeomorphic to , but the fundamental group remains as the quotient does not alter the 1-dimensional homotopy.[62] In low dimensions, explicit computations align with these general results: for instance, since .Homotopy groups

The homotopy groups of the orthogonal group and its connected component exhibit rich structure, particularly in the stable regime where is sufficiently large compared to the degree. The Bott periodicity theorem provides a complete description of the stable homotopy groups of the infinite orthogonal group , asserting that for all . Explicitly, these groups are , , , , , , , , and then the pattern repeats every 8 dimensions. For the special orthogonal group, the stable homotopy groups coincide with those of in positive degrees, since for , reflecting the double cover after the basepoint component. The stable homotopy groups of are intimately connected to real K-theory, or KO-theory. Specifically, the reduced KO-theory groups classify stable real vector bundles over the -sphere up to isomorphism, and by the clutching construction, these are isomorphic to . Thus, , linking the topological structure of to the coefficients of the KO-theory spectrum.[64] This identification underscores the role of Bott periodicity in both algebraic topology and index theory, where the 8-fold periodicity governs the structure of real vector bundles and elliptic operators. For finite , the unstable homotopy groups and can be computed recursively using fibration sequences arising from the inclusions of orthogonal groups. The principal fibration induces a long exact sequence in homotopy: . In the range , the sphere groups vanish, yielding isomorphisms , which stabilize to the Bott groups as . A similar fibration holds for , with fiber . These sequences allow explicit determination of unstable groups by inducting from low dimensions and incorporating the stable values. Geometrically, the homotopy groups admit interpretations in terms of framed cobordisms and immersions. By the Pontryagin-Thom construction and the Smale-Hirsch theorem, elements correspond to framed cobordism classes of -dimensional manifolds immersed (or embedded, in stable ranges) into , where the framing provides a trivialization of the normal bundle. In particular, generators often arise from standard immersions like the Veronese embedding or Haefliger links, classifying oriented manifolds up to framed bordism in the metastable range . The successive connected covers in the Whitehead tower of systematically kill the low-degree homotopy groups, aligning with the stages of Bott periodicity. Starting from , the 0-connected cover is ; the 3-connected cover is the spin group ; the 7-connected cover is the string group ; and the 15-connected cover is the fivebrane group . These structures encode higher refinements of orthogonal frames, such as spin structures for fermions or string structures to cancel anomalies in topological terms.[65]Orthogonal groups over other fields

Indefinite quadratic forms over reals

The indefinite orthogonal group consists of all real matrices such that , where is the diagonal matrix with the identity matrix, corresponding to the preservation of a quadratic form on with signature (that is, positive and negative eigenvalues in the diagonalized form).[66] This quadratic form can be expressed as for .[4] Assuming and , the group has four connected components, determined by the sign of the determinant (which is ) and whether it preserves or reverses the temporal orientation (orthochronous versus antichronous).[67] The identity component consists of those matrices with and preserving the forward light cone, while the full special orthogonal group has two components.[68] A maximal compact subgroup of is , which acts on the positive and negative definite subspaces respectively and is unique up to conjugation.[69] This subgroup is compact because both and are compact Lie groups, and it achieves maximality as no larger compact subgroup can embed without violating the non-compact nature of the overall group.[70] The Iwasawa decomposition of (or more precisely, its identity component) expresses elements as where is the maximal compact, is the vector subgroup of diagonal matrices with positive entries exponentiating the Cartan subalgebra, and is the unipotent radical consisting of upper triangular matrices with 1s on the diagonal.[71] This decomposition is analytic and unique, facilitating harmonic analysis and representation theory on the group.[72] A prominent example is , the Lorentz group, which preserves the Minkowski quadratic form on , central to the mathematical structure of special relativity where it acts as the symmetry group of spacetime intervals. In this case, the four components correspond to proper/improper orthochronous/anti-chronous transformations, with the proper orthochronous subgroup being the connected component of the identity.[73]Complex orthogonal groups

The complex orthogonal group consists of all complex matrices such that , where denotes the transpose of and is the identity matrix. This definition arises from the requirement that elements preserve the standard symmetric bilinear form on . As a subgroup of the general linear group , is a complex algebraic group and a complex Lie group of dimension . The special complex orthogonal group is the normal subgroup of index 2 comprising those elements with determinant 1, defined as . Unlike the real orthogonal group, which is compact, is non-compact as a real manifold of dimension , reflecting its complex structure. Algebraically, serves as the complexification of the real orthogonal group , obtained by extending scalars from to ; this isomorphism holds in the category of algebraic groups. For odd, is of type , and for even, it relates to type , with the special subgroup capturing the semisimple structure. Topologically, has two connected components, distinguished by the sign of the determinant, with forming the identity component. The fundamental group is for , mirroring the real case but computed via the complex manifold structure; higher homotopy groups for coincide with those of due to the stable homotopy equivalence in the complex setting. The complex orthogonal group relates to the complex symplectic group via exterior forms: the alternating form preserved by the symplectic group can be constructed from the wedge product of the symmetric form, linking representations in the exterior algebra. Over , which is algebraically closed, all non-degenerate quadratic forms on an -dimensional space are congruent to the standard sum of squares . Consequently, there are no distinct indefinite complex orthogonal groups analogous to the real indefinite case ; all such groups are isomorphic to the standard .Orthogonal groups over finite fields

Over finite fields with elements, where is a power of a prime, the orthogonal group is defined as the group of matrices over that preserve a non-degenerate quadratic form on the vector space , i.e., matrices such that for all . The classification of these groups depends on the characteristic of the field: when , the theory aligns closely with the real case via Witt decomposition, while in characteristic 2, quadratic forms behave differently due to the coincidence of symmetric and alternating bilinear forms.[16] When , non-degenerate quadratic forms on are classified up to isometry by their dimension and type, determined by the Witt index (the dimension of a maximal isotropic subspace). For odd dimension , there is essentially one isometry class, denoted , with Witt index . For even dimension , there are two distinct classes: the plus type with Witt index (hyperbolic form), and the minus type with Witt index (elliptic form). These types correspond to the Witt groups of quadratic forms over . The plus and minus types are distinguished by the Dickson invariant, a group homomorphism defined via the determinant of the restriction to a hyperbolic plane or, equivalently, by the action on the Clifford algebra; it takes value 0 on and 1 on .[42] The orders of these groups are given by explicit formulas derived from counting isometries via recursive decomposition of the form. For the odd-dimensional case, . For even dimension, and . These formulas reflect the structure: the factor of 2 accounts for determinant , the term arises from the unipotent radical of a Borel subgroup, and the products count the Weyl group contributions. The special orthogonal subgroups have index 2 in except in small cases like . Orthogonal groups over with are generated by reflections and act irreducibly on the natural module , with representations classified via Brauer characters or Deligne-Lusztig theory for simple quotients like .[16][42] In characteristic 2, where for , the situation differs because every symmetric bilinear form is alternating (its diagonal vanishes), so quadratic forms are defined independently via and the associated bilinear form , which is alternating and non-degenerate for non-singular . Orthogonal groups preserve such quadratic forms, but classification relies on the theory of quadratic forms over fields of char 2 rather than just bilinear forms. For odd dimension , there is a unique isometry class of non-singular quadratic forms (up to scaling), yielding with Witt index . For even dimension , there are two classes: hyperbolic (Witt index ) and elliptic (Witt index ), often denoted without but distinguished by the Arf invariant (a -valued functional on the space of quadratic forms modulo hyperbolic planes). In char 2, orthogonal groups must be carefully distinguished from unitary groups over , as the latter preserve sesquilinear forms; however, certain quadratic forms in char 2 induce unitary structures upon extension. The Dickson invariant still applies in even dimension to separate the types, but computations involve the quotient by the kernel of the squaring map. Orders follow similar recursive formulas adjusted for char 2, such as , with analogous expressions for even cases involving factors like . These groups are generated by transvections and act on the natural module, with irreducible representations over studied via modular representation theory.[16][42]Advanced topics

Spinor norm

The spinor norm is a canonical group homomorphism defined for the orthogonal group of a non-degenerate quadratic space over a field of characteristic not 2. This map arises in the arithmetic theory of quadratic forms and captures an invariant of orthogonal transformations modulo squares in . It plays a key role in distinguishing elements within the special orthogonal group , where the kernel of restricted to often coincides with the commutator subgroup .[74] The spinor norm factors through the determinant homomorphism (identified with a subgroup of ) and the Dickson invariant (identified with a subgroup of ), which is determined by the dimension of and the discriminant of . The Dickson invariant is a group homomorphism related to the determinant and the parity of the dimension. This decomposition aids in classifying orthogonal elements and understanding the structure of .[75] Explicitly, the spinor norm can be computed via decompositions into reflections. For a reflection across the hyperplane orthogonal to a non-isotropic vector , . Since every element of is a product of an even or odd number of such reflections (even for ), the spinor norm is multiplicative: if , then . This allows practical computation for products of reflections, independent of the choice up to squares.[75] In the context of quadratic forms over number fields, the spinor norm is instrumental in the Hasse principle, particularly for determining when a quadratic form represents another locally everywhere. It governs the spinor genus of integral quadratic lattices, where two lattices in the same genus are in the same spinor genus if their orthogonal groups share the same spinor norms at all places; this refines the local-global principle by accounting for global obstructions via idele class group mappings. The principle holds for representations by ternary and higher-dimensional forms under spinor norm compatibility. The spinor norm is intimately related to the Clifford algebra and the spin group , the kernel of the reduced norm restricted to the even part, which double covers . The spinor norm on is induced by the Clifford norm on the preimage in , well-defined modulo squares since elements in the center have norm 1. This connection embeds the spinor norm in the broader framework of algebraic groups and automorphic forms.[76]Galois cohomology

The Galois cohomology group , where is a field, is the standard -dimensional vector space over the separable closure equipped with the split quadratic form , and is its orthogonal group, classifies isomorphism classes of quadratic forms of dimension over . Specifically, elements of this pointed set correspond to -torsors over , which via Galois descent are precisely the quadratic spaces over isomorphic to over . The trivial torsor corresponds to the split form , and two quadratic forms are isomorphic over if and only if their associated cocycles are cohomologous. A key invariant arising from this classification is the Clifford invariant, which links quadratic forms to the Brauer group . The even Clifford algebra of a quadratic form is a central simple algebra over of degree for or for , and its class (the 2-torsion) provides a cohomological obstruction to isotropy. Merkurjev's theorem establishes that every element of is represented by such a Clifford algebra for some quadratic form, yielding a surjection from the Witt group of quadratic forms to . This connection extends to central simple algebras with orthogonal involutions, where the Galois cohomology of the associated special orthogonal group encodes similarity classes.[77] Over number fields, local-global principles for quadratic forms are governed by Hasse invariants, which are local cohomological data in for completions at places . The Hasse-Minkowski theorem asserts that a quadratic form over a number field is isotropic if and only if it is isotropic over every , with the global isomorphism class determined by matching local Hasse symbols (products of Hilbert symbols) across all places, up to the product-one relation from class field theory. Failures of stronger principles, such as the Hasse principle for rational points on orthogonal varieties, can be explained by Brauer-Manin obstructions in higher cohomology, but for the classification itself, the local data suffice.[78] Torsors under can be realized geometrically as affine varieties over equipped with a quadratic form such that the associated projective quadric is a principal homogeneous space for the projective orthogonal group . These torsors are trivialized over splitting fields of , and over number fields, their arithmetic is studied via descent from local models; for instance, non-split torsors correspond to anisotropic forms like the norm form of a quaternion algebra, linking back to the Brauer group.[79]Lie algebra

The Lie algebra of the real orthogonal group (or its connected component ) consists of all skew-symmetric real matrices, i.e., , equipped with the Lie bracket . This Lie algebra has dimension , as it is spanned by the basis elements for , where denotes the matrix with a 1 in the -entry and zeros elsewhere.[80][81] The complexification is a semisimple Lie algebra (simple for ) with a Cartan subalgebra formed by diagonal matrices in a suitable basis. Its root system relative to depends on the parity of : if (type ), then , where is the standard basis of ; if (type ), then . The root spaces are one-dimensional for each root , and the algebra decomposes as . A Chevalley basis for consists of the Cartan elements (corresponding to simple roots), positive root vectors , and negative root vectors , with structure constants that are integers, ensuring integrality properties useful for constructing Chevalley groups.[82][83] The adjoint representation , given by , is faithful for , as is semisimple with trivial center in these cases (noting that is semisimple but not simple). This representation embeds as a subalgebra of skew-symmetric matrices acting on itself.[80][84] The Killing form on is negative definite, which characterizes it as the compact real form of the complex orthogonal Lie algebra . Explicitly, for , confirming non-degeneracy and negative definiteness. This property aligns with the compactness of and facilitates the study of representations and invariant bilinear forms.[85][86]Related groups and spaces

Lie subgroups and supergroups

The special orthogonal group is a connected Lie subgroup of index 2 in the orthogonal group , defined as the kernel of the determinant homomorphism . It consists of all proper rotations preserving the standard Euclidean inner product on , and its Lie algebra is the space of skew-symmetric matrices . As a simple Lie group for , plays a central role in the structure of , which is a semidirect product .[3] The orthogonal group embeds as a closed Lie subgroup of via the stabilizer of a unit vector, such as the first standard basis vector . This embedding identifies with the block matrices of the form , where , preserving the orthogonal structure on the orthogonal complement of . Such stabilizers are maximal parabolic subgroups in the context of representation theory, and for , is a maximal connected Lie subgroup of up to conjugacy, except in dimensions 4 and 8 where exceptional isomorphisms occur.[87] Finite Lie subgroups of include the dihedral groups , which embed into for as the symmetries of a regular -gon in the -plane. The dihedral group is generated by a rotation by and a reflection, with presentation , and it acts faithfully on while fixing the higher coordinates. These groups are examples of reflection groups and appear in classifications of finite subgroups of , alongside cyclic and polyhedral groups for higher dimensions.[88] The conformal orthogonal group , also denoted , extends by incorporating positive scalar multiplications, forming the semidirect product where scalings act by conjugation. It consists of similitudes—linear transformations satisfying for some —and serves as the structure group for conformal geometry on Riemannian manifolds. The full group including orientation-reversing elements is , but the connected component is , with Lie algebra . This extension arises naturally in the study of Möbius transformations and angle-preserving maps.[89] In supergeometry, the orthogonal supergroup is a Lie supergroup preserving a consistent super quadratic form on the superspace , where the even (bosonic) part is the standard symmetric bilinear form on and the odd (fermionic) part involves an antisymmetric structure on . More commonly realized as the orthosymplectic supergroup , it has even subgroup and odd part given by the orthosymplectic Lie superalgebra , which includes matrices satisfying for the super metric with the symplectic form. This supergroup extends classical orthogonal groups to supersymmetric settings, appearing in representations of super Lie algebras and invariant theory for superalgebras, where the first fundamental theorem describes invariants under its action.[90][91] The Pin and Spin groups provide double cover extensions of the orthogonal groups. The Spin group is the unique simply connected double cover of for , with kernel , constructed as the multiplicative group of even Clifford algebra elements of norm 1. Similarly, the Pin group double covers , incorporating odd Clifford elements, and splits into and depending on the signature. These covers are essential for spinor representations and are Lie groups whose Lie algebras are , facilitating the study of framings and Dirac operators.[92] An example of embeddings involving the orthogonal group is the faithful representation of the general linear group into the indefinite orthogonal group , acting on by , preserving the hyperbolic form . This realizes as a closed Lie subgroup of an orthogonal group in dimension , highlighting connections between linear and orthogonal structures in higher dimensions.[93]Discrete subgroups