Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

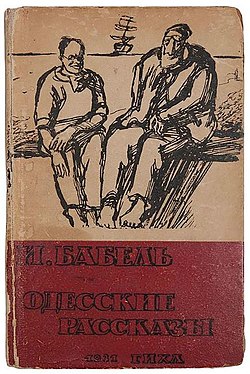

Odessa Stories

View on WikipediaOdessa Stories (Russian: Одесские рассказы, romanized: Odesskiye rasskazy), also known as Tales of Odessa, is a collection of four short stories by Isaac Babel, set in Odessa in the last days of the Russian Empire and the Russian Revolution. Published individually in Soviet magazines between 1921 and 1924 and collected into a book in 1931, they deal primarily with a group of Jewish thugs that live in Moldavanka, a ghetto of Odessa. Their leader is Benya Krik, known as the King, and loosely based on the historical figure Mishka Yaponchik.[1]

Key Information

In 1926, Babel adapted parts of the first two stories and additional content as a screenplay, Benya Krik, directed by Vladimir Vilner and released in 1927, as well as the play Sunset, which premiered in October 1927.

Stories

[edit]The four stories originally included in the 1931 collection are:

- The King (Король) (1921)

- How It Was Done in Odessa (Как это делалось в Одессе) (1923)

- The Father (Отец) (1924)

- Lyubka the Cossack (Любка Казак) (1924)

The following stories have at times been included by editors as part of the "Odessa Stories" cycle as well:[2]

- Fairness in Brackets (Справедливость в скобках) (1921)

- You Missed the Boat, Captain! (1924)

- End of the Almshouse (Конец богадельни) (written 1920–29, published 1932)

- Froim Grach (Фроим Грач) (written 1933, published 1963)

- Sunset (Закат) (written 1924–35, published 1963)

- Karl-Yankel (Карл-Янкель) (1931)

Translations

[edit]- Walter Morison, in The Collected Stories (1955)

- Andrew R. MacAndrew: Lyubka the Cossack and Other Stories (1963)

- David McDuff, in Collected Stories (1994, Penguin)

- Peter Constantine, in The Complete Works of Isaac Babel (Norton, 2002)

- Boris Dralyuk, in Odessa Stories (Pushkin Press, 2016)

- Val Vinokur, in The Essential Fictions (Northwestern University Press, 2017)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tanny, Jarrod (2011). City of Rogues and Schnorrers: Russia's Jews and the Myth of Old Odessa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. ch. 3. ISBN 978-0-253-22328-9.

- ^ Briker, Boris (1994). "The Underworld of Benia Krik and I. Babel's "Odessa Stories"". Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes. 36 (1/2): 115–134. doi:10.1080/00085006.1994.11092049. ISSN 0008-5006. JSTOR 40870776.

External links

[edit]- Benya Krik at the Internet Movie Database.