Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

STRAP

View on Wikipedia

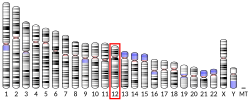

Serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the STRAP gene.[6]

SMAD2, encoded by the SMAD2 gene in humans, is a pivotal member of the SMAD protein family, exhibiting homology with the Drosophila gene 'mothers against decapentaplegic' (Mad) and the C. elegans gene Sma. Functioning as a crucial signal transducer and transcriptional modulator, SMAD2 assumes a central role in diverse cellular processes through its mediation of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta signaling pathway. Its regulatory purview encompasses the orchestration of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation.

SMAD2 engages in a dynamic interplay with the STRAP (Serine-Threonine Kinase Receptor-Associated Protein) gene. This interaction is characterized by the recruitment of SMAD2 to TGF-beta receptors through its association with the SMAD anchor for receptor activation (SARA) protein. Upon stimulation by TGF-beta, SMAD2 undergoes phosphorylation by TGF-beta receptors, leading to its dissociation from SARA and subsequent association with the SMAD4 family member. This orchestrated sequence of events is crucial for the translocation of SMAD2 into the cell nucleus. Within the nucleus, SMAD2 binds to target promoters and collaborates with other cofactors to form a transcription repressor complex. This cooperative interaction underscores the intricate regulatory network in which SMAD2 participates.

SMAD2's versatility extends beyond TGF-beta signaling, as it can also be phosphorylated by activin type 1 receptor kinase, enabling its mediation of signals from activin. The existence of multiple transcript variants resulting from alternative splicing further highlights the adaptability of SMAD2 in responding to various cellular cues.

The nomenclature of SMAD proteins, including SMAD2, draws from their homology with both the Drosophila protein MAD and the C. elegans protein SMA, emphasizing their evolutionary conservation. This nomenclature finds its roots in Drosophila research, where a mutation in the MAD gene of the mother repressed the decapentaplegic gene in the embryo, providing foundational insights into the regulatory network orchestrated by SMAD2 across species.

Apoptosis

[edit]The interaction between ASK1 and STRAP is characterized by specific domains, with the C-terminal domain of ASK1 and the fourth and sixth WD40 repeats of STRAP playing crucial roles.[7]

Cysteine residues, particularly Cys1351 and Cys1360 in ASK1, and Cys152 and Cys270 in STRAP, are identified as essential for mediating the binding between these two proteins. ASK1 is found to phosphorylate STRAP at Thr175 and Ser179, suggesting a potential regulatory role for STRAP phosphorylation in ASK1 activity.

Functional assays demonstrate that wild-type STRAP, but not specific mutants, inhibits ASK1-mediated signaling to JNK and p38 kinases. This inhibitory effect is attributed to the modulation of complex formation between ASK1 and its negative regulators, such as thioredoxin and 14-3-3, or the disruption of complex formation between ASK1 and its substrate MKK3.

Moreover, STRAP exhibits a dose-dependent suppression of H2O2-induced apoptosis through direct interaction with ASK1, underscoring its negative regulatory role in ASK1 activity within the cellular context. The study also hints at the potential involvement of STRAP in PDK1-mediated signaling, given its previously identified role as a positive regulator of PDK1.

Diseases

[edit]Conditions linked to STRAP encompass Spastic Paraplegia 8, Autosomal Dominant, and Childhood Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Its involvement extends to pathways such as Signaling by TGFB family members and TGF-beta receptor signaling activating SMADs. Noteworthy Gene Ontology (GO) annotations associated with this gene involve RNA binding and kinase activity

Early follicle development in mice

[edit]The molecular mechanisms governing the development of small, gonadotrophin-independent follicles remain poorly understood, with TGFB ligands emerging as key players. Canonical TGFB signaling relies on intracellular SMAD proteins that modulate transcription. Notably, STRAP has been recognized in various tissues as an inhibitor of the TGFB-SMAD signaling pathway. This study aimed to elucidate the expression and function of STRAP in early follicle development.

Through qPCR analysis,[8] similar expression profiles were observed for Strap, Smad3, and Smad7 in immature ovaries from mice aged 4–16 days, encompassing diverse populations of early growing follicles. Immunofluorescence revealed co-localization of STRAP and SMAD2/3 proteins in granulosa cells of small follicles. Employing a culture model with neonatal mouse ovary fragments rich in small non-growing follicles, interventions such as Strap knockdown using siRNA and STRAP protein inhibition via immuno-neutralization led to a reduction in small, non-growing follicles. Conversely, there was an increase in the proportion and size of growing follicles, implying that inhibiting STRAP facilitates follicle activation.

Recombinant STRAP protein had no impact on small, non-growing follicles but increased the mean oocyte size of growing follicles in the neonatal ovary model and stimulated the growth of isolated preantral follicles in vitro. In summary, these findings demonstrate the expression of STRAP in the mouse ovary and its ability to modulate the development of small follicles in a stage-dependent manner.

Interactions

[edit]STRAP has been shown to interact with:

The nomenclature of SMAD proteins, derived from homology with Drosophila MAD and C. elegans SMA, reflects their evolutionary conservation, rooted in Drosophila research where a MAD gene mutation in the mother repressed the decapentaplegic gene in the embryo. This underscores the fundamental role of SMAD2 in cellular regulation across species. SMAD2, encoded by the SMAD2 gene, is a key player in cellular processes, mediating the transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta signaling pathway. Interacting dynamically with the STRAP gene, SMAD2 is recruited to TGF-beta receptors through association with the SMAD anchor for receptor activation (SARA) protein. Upon TGF-beta stimulation, SMAD2 undergoes phosphorylation, dissociating from SARA and forming a complex with the SMAD4 family member, facilitating nuclear translocation. Within the nucleus, SMAD2 binds to target promoters and collaborates with cofactors to form a transcription repressor complex. This interaction underscores the intricate regulatory network governed by SMAD2. Beyond TGF-beta signaling, SMAD2's versatility is evident in its phosphorylation by activin type 1 receptor kinase, enabling mediation of signals from activin. Multiple transcript variants resulting from alternative splicing highlight the adaptability of SMAD2 in responding to diverse cellular cues.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000023734 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000030224 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Seong HA, Jung H, Ha H (April 2007). "NM23-H1 tumor suppressor physically interacts with serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein, a transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor-interacting protein, and negatively regulates TGF-beta signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (16): 12075–12096. doi:10.1074/jbc.m609832200. PMID 17314099.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: STRAP serine/threonine kinase receptor associated protein".

- ^ Jung H, Seong HA, Manoharan R, Ha H (January 2010). "Serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein inhibits apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 function through direct interaction". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1074/jbc.m109.045229. PMC 2804202. PMID 19880523.

- ^ Sharum IB, Granados-Aparici S, Warrander FC, Tournant FP, Fenwick MA (February 2017). "Serine threonine kinase receptor associated protein regulates early follicle development in the mouse ovary". Reproduction. 153 (2): 221–231. doi:10.1530/REP-16-0612. ISSN 1470-1626. PMID 27879343.

- ^ a b c d e f Datta PK, Moses HL (May 2000). "STRAP and Smad7 synergize in the inhibition of transforming growth factor beta signaling". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 20 (9): 3157–3167. doi:10.1128/mcb.20.9.3157-3167.2000. PMC 85610. PMID 10757800.

- ^ a b Datta PK, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Moses HL (December 1998). "Identification of STRAP, a novel WD domain protein in transforming growth factor-beta signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (52): 34671–34674. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.52.34671. PMID 9856985.

Further reading

[edit]- Hunt SL, Hsuan JJ, Totty N, Jackson RJ (February 1999). "unr, a cellular cytoplasmic RNA-binding protein with five cold-shock domains, is required for internal initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA". Genes & Development. 13 (4): 437–448. doi:10.1101/gad.13.4.437. PMC 316477. PMID 10049359.

- Matsuda S, Katsumata R, Okuda T, Yamamoto T, Miyazaki K, Senga T, et al. (January 2000). "Molecular cloning and characterization of human MAWD, a novel protein containing WD-40 repeats frequently overexpressed in breast cancer". Cancer Research. 60 (1): 13–17. PMID 10646843.

- Datta PK, Moses HL (May 2000). "STRAP and Smad7 synergize in the inhibition of transforming growth factor beta signaling". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 20 (9): 3157–3167. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.9.3157-3167.2000. PMC 85610. PMID 10757800.

- Zhang QH, Ye M, Wu XY, Ren SX, Zhao M, Zhao CJ, et al. (October 2000). "Cloning and functional analysis of cDNAs with open reading frames for 300 previously undefined genes expressed in CD34+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells". Genome Research. 10 (10): 1546–1560. doi:10.1101/gr.140200. PMC 310934. PMID 11042152.

- Wiemann S, Weil B, Wellenreuther R, Gassenhuber J, Glassl S, Ansorge W, et al. (March 2001). "Toward a catalog of human genes and proteins: sequencing and analysis of 500 novel complete protein coding human cDNAs". Genome Research. 11 (3): 422–435. doi:10.1101/gr.GR1547R. PMC 311072. PMID 11230166.

- Iriyama C, Matsuda S, Katsumata R, Hamaguchi M (2001). "Cloning and sequencing of a novel human gene which encodes a putative hydroxylase". Journal of Human Genetics. 46 (5): 289–292. doi:10.1007/s100380170081. PMID 11355021.

- Pillai RS, Grimmler M, Meister G, Will CL, Lührmann R, Fischer U, Schümperli D (September 2003). "Unique Sm core structure of U7 snRNPs: assembly by a specialized SMN complex and the role of a new component, Lsm11, in histone RNA processing". Genes & Development. 17 (18): 2321–2333. doi:10.1101/gad.274403. PMC 196468. PMID 12975319.

- Ozdamar B, Bose R, Barrios-Rodiles M, Wang HR, Zhang Y, Wrana JL (March 2005). "Regulation of the polarity protein Par6 by TGFbeta receptors controls epithelial cell plasticity". Science. 307 (5715): 1603–1609. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1603O. doi:10.1126/science.1105718. PMID 15761148. S2CID 41013935.

- Barrios-Rodiles M, Brown KR, Ozdamar B, Bose R, Liu Z, Donovan RS, et al. (March 2005). "High-throughput mapping of a dynamic signaling network in mammalian cells". Science. 307 (5715): 1621–1625. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1621B. doi:10.1126/science.1105776. PMID 15761153. S2CID 39457788.

- Carissimi C, Baccon J, Straccia M, Chiarella P, Maiolica A, Sawyer A, et al. (April 2005). "Unrip is a component of SMN complexes active in snRNP assembly". FEBS Letters. 579 (11): 2348–2354. Bibcode:2005FEBSL.579.2348C. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.034. PMID 15848170. S2CID 10276186.

- Grimmler M, Otter S, Peter C, Müller F, Chari A, Fischer U (October 2005). "Unrip, a factor implicated in cap-independent translation, associates with the cytosolic SMN complex and influences its intracellular localization". Human Molecular Genetics. 14 (20): 3099–3111. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi343. PMID 16159890.

- Rual JF, Venkatesan K, Hao T, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Dricot A, Li N, et al. (October 2005). "Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network". Nature. 437 (7062): 1173–1178. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1173R. doi:10.1038/nature04209. PMID 16189514. S2CID 4427026.

- Guo D, Han J, Adam BL, Colburn NH, Wang MH, Dong Z, et al. (December 2005). "Proteomic analysis of SUMO4 substrates in HEK293 cells under serum starvation-induced stress". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 337 (4): 1308–1318. Bibcode:2005BBRC..337.1308G. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.191. PMID 16236267.

- Seong HA, Jung H, Choi HS, Kim KT, Ha H (December 2005). "Regulation of transforming growth factor-beta signaling and PDK1 kinase activity by physical interaction between PDK1 and serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (52): 42897–42908. doi:10.1074/jbc.M507539200. PMID 16251192.

- Kimura K, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y, Ota T, Nishikawa T, Yamashita R, et al. (January 2006). "Diversification of transcriptional modulation: large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes". Genome Research. 16 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1101/gr.4039406. PMC 1356129. PMID 16344560.

- Carissimi C, Saieva L, Gabanella F, Pellizzoni L (December 2006). "Gemin8 is required for the architecture and function of the survival motor neuron complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (48): 37009–37016. doi:10.1074/jbc.M607505200. PMID 17023415.

- Seong HA, Jung H, Ha H (April 2007). "NM23-H1 tumor suppressor physically interacts with serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein, a transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor-interacting protein, and negatively regulates TGF-beta signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (16): 12075–12096. doi:10.1074/jbc.M609832200. PMID 17314099.