Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

IP fragmentation

View on Wikipedia

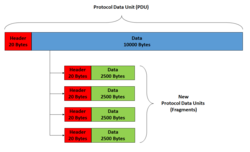

IP fragmentation is an Internet Protocol (IP) process that breaks packets into smaller pieces (fragments), so that the resulting pieces can pass through a link with a smaller maximum transmission unit (MTU) than the original packet size. The fragments are reassembled by the receiving host.

The details of the fragmentation mechanism, as well as the overall architectural approach to fragmentation, are different between IPv4 and IPv6.

Process

[edit]RFC 791 describes the procedure for IP fragmentation, and transmission and reassembly of IP packets.[1] RFC 815 describes a simplified reassembly algorithm.[2] The Identification field along with the foreign and local internet address and the protocol ID, and Fragment offset field along with Don't Fragment and More Fragments flags in the IP header are used for fragmentation and reassembly of IP packets.[1]: 24 [2]: 9

If a receiving host receives a fragmented IP packet, it has to reassemble the packet and pass it to the higher protocol layer. Reassembly is intended to happen in the receiving host but in practice, it may be done by an intermediate router, for example, network address translation (NAT) may need to reassemble fragments in order to translate data streams.[3]

IPv4 and IPv6 differences

[edit]

Under IPv4, a router that receives a network packet larger than the next hop's MTU has two options: drop the packet if the Don't Fragment (DF) flag bit is set in the packet's header and send an Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) message which indicates the condition Fragmentation Needed (Type 3, Code 4), or fragment the packet and send it over the link with a smaller MTU. Although originators may produce fragmented packets, IPv6 routers do not have the option to fragment further. Instead, network equipment is required to deliver any IPv6 packets or packet fragments smaller than or equal to 1280 bytes and IPv6 hosts are required to determine the optimal MTU through Path MTU Discovery before sending packets.

Though the header formats are different for IPv4 and IPv6, analogous fields are used for fragmentation, so the same algorithm can be reused for IPv4 and IPv6 fragmentation and reassembly.

In IPv4, hosts must make a best-effort attempt to reassemble fragmented IP packets with a total reassembled size of up to 576 bytes. They may also attempt to reassemble fragmented IP packets larger than 576 bytes, but they are also permitted to silently discard such larger packets. Applications are recommended to refrain from sending packets larger than 576 bytes unless they have prior knowledge that the remote host is capable of accepting or reassembling them.[1]: 12

In IPv6, hosts must make a best-effort attempt to reassemble fragmented packets with a total reassembled size of up to 1500 bytes, larger than IPv6's minimum MTU of 1280 bytes.[4] Fragmented packets with a total reassembled size larger than 1500 bytes may optionally be silently discarded. Applications relying upon IPv6 fragmentation to overcome a path MTU limitation must explicitly fragment the packet at the point of origin; however, they should not attempt to send fragmented packets with a total size larger than 1500 bytes unless they know in advance that the remote host is capable of reassembly.

Impact on network forwarding

[edit]When a network has multiple parallel paths, technologies like LAG and CEF split traffic across the paths according to a hash algorithm. One goal of the algorithm is to ensure all packets of the same flow are sent out the same path to minimize unnecessary packet reordering.

IP fragmentation can cause excessive retransmissions when fragments encounter packet loss and reliable protocols such as TCP must retransmit all of the fragments in order to recover from the loss of a single fragment.[5] Thus, senders typically use two approaches to decide the size of IP packets to send over the network. The first is for the sending host to send an IP packet of size equal to the MTU of the first hop of the source-destination pair. The second is to run the Path MTU Discovery algorithm[6] to determine the path MTU between two IP hosts so that IP fragmentation can be avoided.

As of 2020[update], IP fragmentation is considered fragile and often undesired due to its security impact.[7]

See also

[edit]- IPv4 § Fragmentation and reassembly

- IPv6 packet § Fragmentation

- IP fragmentation attack

- Protocol data unit and Service data unit

- Segmentation and reassembly – Arranging data into cells in an ATM network

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Internet Protocol, Information Sciences Institute, September 1981, RFC 791

- ^ a b David D. Clark (July 1982), IP Datagram Reassembly Algorithms, RFC 815

- ^ Hain, Tony L. (November 2000), Architectural Implications of NAT, RFC 2993

- ^ S. Deering; R. Hinden (December 1998), Internet Protocol, Version 6 (IPv6) Specification, RFC 2460

- ^ Christopher A. Kent, Jeffrey C. Mogul. "Fragmentation Considered Harmful" (PDF).

- ^ Deering, Steve E.; Mogul, Jeffrey (November 1990), Path MTU Discovery, RFC 1191

- ^ IP Fragmentation Considered Fragile. September 2020. doi:10.17487/RFC8900. RFC 8900.

External links

[edit]IP fragmentation

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

IP fragmentation is the process of dividing an Internet Protocol (IP) datagram into smaller fragments when its size exceeds the Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) of a network link, allowing transmission across diverse network paths with varying size constraints.[1] This mechanism ensures that oversized datagrams can be forwarded without requiring the sender to know the MTU of every link along the route, thereby preventing packet drops due to size limitations.[1] The primary purpose of IP fragmentation is to support internetworking in heterogeneous environments, where networks may impose different maximum packet sizes, enabling seamless data transmission across interconnected packet-switched systems.[1] By permitting intermediate routers to fragment datagrams as needed, it promotes the scalability and robustness of the early Internet, avoiding the need for uniform packet sizes across all networks.[1] Introduced in the IPv4 specification as part of the DARPA Internet Program in 1981, IP fragmentation was essential for the protocol's design to handle "small packet" networks within larger internetworks.[1] For instance, a 2000-byte datagram originating on a network supporting larger packets would be fragmented into multiple smaller pieces—each no larger than 1500 bytes—to traverse a link with that MTU, with reassembly occurring at the destination.[1]Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU)

The Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) is defined as the largest size of an IP datagram, measured in bytes, that can be transmitted over a specific data link without requiring fragmentation at the IP layer.[1] This limit is enforced by the underlying physical and data link layer protocols, ensuring that packets fit within the capabilities of network interfaces and transmission media. In network design, the MTU serves as a foundational constraint that influences packet sizing decisions to optimize efficiency and avoid unnecessary processing overhead. There are two primary types of MTU relevant to IP networks: the link MTU, which represents the hardware-imposed maximum packet size for a single network interface or link, and the path MTU, which is the smallest link MTU among all segments in an end-to-end path between source and destination.[5] The link MTU is a static property determined by the link technology, while the path MTU accounts for variations across heterogeneous networks, often requiring dynamic determination to prevent issues. Standard link MTU values include 1500 bytes for classic Ethernet networks, as established for IP datagram transmission over Ethernet. Jumbo frames extend this to up to 9000 bytes on supported Ethernet implementations to reduce overhead in high-speed environments, though this is not universally standardized. For protocol compliance, IPv4 specifies a minimum link MTU of 68 bytes to accommodate the smallest viable datagram, including header and minimal payload, while IPv6 mandates a minimum link MTU of 1280 bytes across all links to simplify processing and ensure interoperability.[1][5][2] Exceeding the MTU on a link triggers IP fragmentation if permitted by the packet's Don't Fragment (DF) flag, dividing the datagram into smaller pieces for transmission, or results in packet discard accompanied by an ICMP "Fragmentation Needed" error message if DF is set, informing the sender to reduce packet size.[6] These outcomes can degrade network performance by increasing latency due to reassembly delays at the destination and reducing throughput from the additional overhead of fragment headers and potential retransmissions.[7] In path scenarios, mismatches amplify these effects, underscoring the MTU's role in balancing packet efficiency with reliable delivery across diverse network topologies.IPv4 Fragmentation

Header Fields and Identification

The IPv4 header includes several fields dedicated to fragmentation identification and control, enabling routers to divide oversized datagrams and endpoints to reassemble them correctly. The Identification field is a 16-bit value assigned by the originating host to uniquely label all fragments belonging to the same original datagram. This field, combined with the source address, destination address, and protocol fields, allows receiving hosts to match and group fragments accurately during reassembly, preventing intermixing with fragments from other datagrams.[8] Adjacent to the Identification field are the Flags (3 bits) and Fragment Offset (13 bits), which together manage fragmentation behavior and positioning. The Flags consist of three bits: bit 0 (reserved, always set to 0), bit 1 for the Don't Fragment (DF) flag, and bit 2 for the More Fragments (MF) flag. The DF flag, when set to 1, instructs routers not to fragment the datagram; if fragmentation is required along the path, the router discards the packet and sends an ICMP "Fragmentation Needed" message (Type 3, Code 4) back to the sender. The MF flag is set to 1 in all fragments except the last one, signaling that additional fragments follow; it is 0 for the final fragment. The Fragment Offset field specifies the position of the fragment's data relative to the start of the original datagram's data, measured in units of 8 bytes (64 bits), with the first fragment always having an offset of 0 and subsequent fragments using cumulative offsets that are multiples of 8.[8] Identification and these fields work in tandem to ensure reliable reassembly: all fragments share the same Identification value, while the Fragment Offset provides the exact byte offset (when multiplied by 8) for ordering, and the MF flag indicates completion. For instance, consider an original datagram with 2000 bytes of total length (including a 20-byte header, so 1980 bytes of data) that must be fragmented due to a 1500-byte MTU path; assuming no IP options, the first fragment might carry 1480 bytes of data (offset 0, MF=1), the second 496 bytes of data (offset 185, since 1480/8=185, MF=1), and the third the remainder of 4 bytes (offset 247, since (1480+496)/8=247, MF=0), all sharing the same 16-bit Identification value. This mechanism, defined in the IPv4 specification, supports efficient handling of variable network conditions without requiring changes to upper-layer protocols.[8][9]Fragmentation Process

The fragmentation process in IPv4 occurs when a datagram's total length exceeds the maximum transmission unit (MTU) of the outgoing network interface, requiring the sender (source host) or an intermediate router to divide it into smaller fragments that can be transmitted.[1] This division happens only if the Don't Fragment (DF) flag in the IPv4 header is not set; if DF is set, the datagram is discarded, and an ICMP "Fragmentation Needed" message is sent back to the source with the MTU of the next hop.[1] Intermediate routers perform fragmentation as needed to forward the datagram, while end hosts typically avoid it by employing Path MTU Discovery to determine and use the smallest MTU along the path beforehand.[7] The process begins by copying the original IPv4 header to each fragment, adjusting specific fields as necessary. The Internet Header Length (IHL) field may change if options are present, but the header size is at least 20 bytes. IP options are included in the first fragment; those with the "copied" flag set in their type octet (e.g., security or source routing options) are duplicated in all subsequent fragments, while others (e.g., record route or timestamp) appear only in the first.[1] The payload (data portion) of the original datagram is then divided into chunks, ensuring that the data length of all fragments except the last is a multiple of 8 bytes to align with the fragment offset field's 8-byte unit scaling.[1] To determine fragment sizes, the maximum data payload per fragment is calculated as , where is the header length in bytes (minimum 20).[1] The number of full-sized fragments is , where is the original datagram's total length and is the maximum data size per fragment; the remainder forms the last fragment. For each fragment, the Fragment Offset field is set to the cumulative data length of prior fragments divided by 8 (in 13-bit units), the More Fragments (MF) flag is set to 1 for all but the last fragment, and the Total Length field is updated to header size plus the fragment's data length. The Header Checksum is recalculated for each fragment due to these changes.[1] For example, consider a 3000-byte datagram (20-byte header, 2980-byte payload) traversing a link with 1500-byte MTU. The maximum data per fragment is 1480 bytes (). The first fragment carries 1480 bytes of data (offset 0, MF=1, total length 1500), the second carries another 1480 bytes (offset 185, since , MF=1, total length 1500), and the last carries the remaining 20 bytes (offset 370, MF=0, total length 40).[1]Reassembly Process

In IPv4, reassembly of fragmented datagrams is performed exclusively by the destination end host, while intermediate routers forward individual fragments without attempting reconstruction.[10] The receiving host identifies fragments belonging to the same original datagram using the Identification field in the IP header, which must match across all fragments from a given source-destination pair with the same protocol.[10] Fragments are ordered and positioned based on the Fragment Offset field, expressed in units of 8 octets, and the More Fragments (MF) flag, which is set to 1 for all but the last fragment.[10] The reassembly process begins when the first fragment arrives, prompting the host to allocate a buffer for the datagram. Subsequent fragments are buffered and inserted into this space according to their offset values, with the host checking for gaps, overlaps, or duplicates.[10] Overlapping fragments are resolved by retaining the most recent data in case of conflicts, and any detected errors, such as invalid offsets or mismatched identifications, result in discarding the entire set.[10] Reassembly proceeds incrementally until the MF flag is 0 on the final fragment, signaling completeness; at this point, the payloads are concatenated in offset order to form the original datagram, and the IP header's checksum is recomputed over the reassembled header before passing the datagram to the upper-layer protocol.[10] If reassembly is incomplete due to lost fragments, the process waits until a timeout expires, after which all buffered fragments for that datagram are discarded.[11] Hosts must implement a reassembly timer, with a recommended duration between 60 and 120 seconds starting from the arrival of the first fragment, to accommodate potential delays in fragment delivery.[11] This timeout ensures resource reclamation but introduces the risk that partial datagrams are dropped entirely upon expiration, without partial delivery to higher layers.[11] The process demands significant memory at the receiver, as all fragments must be held simultaneously until reassembly completes or times out, potentially straining hosts under high fragmentation loads.[10] For example, consider three fragments sharing Identification value 12345: the first with offset 0 and MF=1 (carrying the initial 1480 octets of data), the second with offset 185 (1480 octets, MF=1), and the third with offset 370 (740 octets, MF=0). The receiver buffers these, verifies sequential offsets without gaps (0 to 185, then 185 to 370), and upon the last fragment's arrival, concatenates the data into a 3700-octet original payload before recomputing the checksum.[10]IPv6 Fragmentation

Key Differences from IPv4

IPv6 fragmentation adheres to the end-to-end principle more strictly than IPv4 by discouraging fragmentation at intermediate routers, instead requiring senders to perform fragmentation at the source or utilize Path MTU Discovery to avoid it altogether. In contrast to IPv4, where routers can fragment packets using fields in the base header, IPv6 places no fragmentation-related fields in its fixed 40-byte base header; fragmentation information is instead carried in a dedicated Fragment Header extension, identified by a Next Header value of 44. A key structural difference is IPv6's enforcement of a minimum link MTU of 1280 bytes, which minimizes the occurrence of fragmentation for small packets compared to IPv4's more variable MTU handling without such a universal minimum. Unlike IPv4's Don't Fragment (DF) flag, which signals routers to drop oversized packets and send ICMP messages, IPv6 lacks an equivalent flag in its headers; oversized packets are either dropped silently by routers or, if supported, trigger an ICMPv6 "Packet Too Big" message to inform the sender. These mechanisms were first specified in RFC 2460 in December 1998, with updates and clarifications provided in RFC 8200 in July 2017 to address errata and improve interoperability. For instance, in IPv6, if the path MTU is unknown, the sender must proactively fragment the original packet into pieces no larger than 1280 bytes before transmission, ensuring end-to-end delivery without relying on router intervention.Extension Headers and Processing

In IPv6, fragmentation is facilitated by the Fragment Header, an extension header that allows source nodes to divide oversized packets into smaller fragments for transmission across networks with varying maximum transmission unit (MTU) sizes.[12] This header is inserted only by the originating source, as intermediate routers do not perform fragmentation; instead, they drop oversized packets and notify the source via an ICMPv6 Packet Too Big message (Type 2).[12] Unlike IPv4, where fragmentation can occur at any router, IPv6 enforces end-to-end fragmentation and reassembly to simplify routing and improve efficiency.[12] The Fragment Header consists of 8 octets and follows the IPv6 base header or any preceding extension headers, with its presence indicated by a Next Header value of 44 in the previous header.[12] Its structure is as follows:| Field | Size (bits) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Next Header | 8 | Identifies the type of the initial header of the Fragmentable Part (upper-layer or subsequent extension header).[12] |

| Reserved | 8 | Set to zero by the sender and ignored by the receiver.[12] |

| Fragment Offset | 13 | Indicates the offset of this fragment from the start of the original Fragmentable Part, measured in units of 8 octets (thus supporting offsets up to 65,528 octets).[12] |

| Reserved2 (Res) | 2 | Set to zero by the sender and ignored by the receiver.[12] |

| M Flag | 1 | More Fragments flag; set to 1 if additional fragments follow, or 0 for the last fragment.[12] |

| Identification | 32 | A unique identifier for the original packet, shared across all fragments with the same source and destination addresses to enable reassembly.[12] |