Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

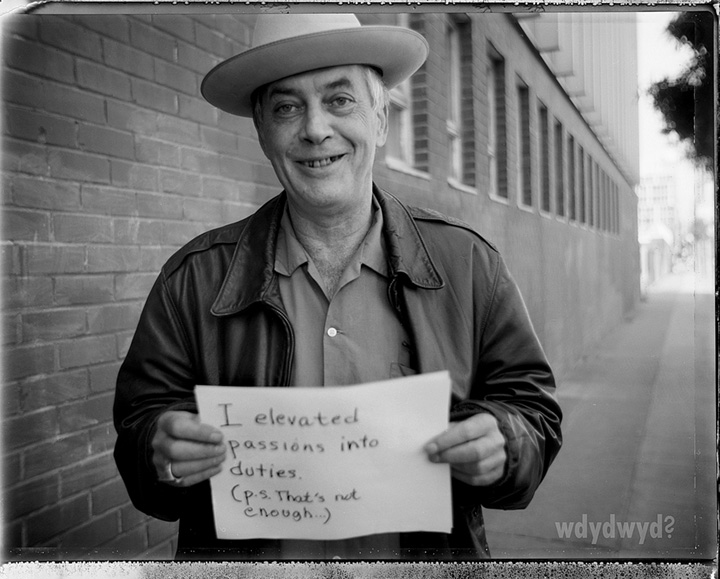

Larry Harvey

View on Wikipedia

Larry Harvey (January 11, 1948 – April 28, 2018) was an American artist, philanthropist and activist. He was the main co-founder of the Burning Man event, along with his friend Jerry James.[1]

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Born in San Francisco, Harvey grew up in Portland, Oregon, where he was raised in the Parkrose neighborhood.[2] He graduated from Parkrose High School in 1966.[3] After high School, he joined the army and served as a clerk stationed in Germany.[4] He later attended Portland State University.[5]

Burning Man

[edit]Burning Man started in 1986 on the evening of the summer solstice. An effigy of a man was taken to San Francisco's Baker Beach and set on fire. A small crowd gathered and soon the burning of the man became an annual event. Over the next four years the attendees grew to more than 800 people. In 1990, in collaboration with the SF Cacophony Society, the event moved to the Black Rock Desert, Nevada, and took place over Labor Day weekend. From a three-day, 80-person "zone trip," Burning Man became an eight-day counter culture event with 70,000 participants from all over the world.

In 1997, six of the main organizers formed Black Rock City LLC to manage the event, with Harvey as the executive director, a position he held until his death. Harvey was also the president of the Black Rock Arts Foundation, a non-profit art grant foundation for promoting interactive collaborative public art installations in communities outside of Black Rock City.

Philosophy and activities

[edit]Larry Harvey was a voracious reader and was heavily influenced by works such as Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community by Robert Putnam, The Varieties of Religious Experience by William James, and the writings of Sigmund Freud.[6]

He scripted and co-chaired/curated the Burning Man art department and its annual event theme. Harvey was the main spokesperson and political strategist for the Burning Man organization. He had been featured in such engagements as San Francisco's Grace Cathedral "Radical Ritual" with Alan Jones, the Oxford Student Union, Cooper Union in New York City,[7] Harvard's International Conference on Internet and Society as a panelist,[8] and the San Francisco Commonwealth Club.[9]

Death

[edit]Harvey died on April 28, 2018, due to complications related to a stroke he had suffered earlier in the same month.[10][11] He was 70 years old.

References

[edit]- ^ Jacques, Adam (August 23, 2014). "Larry Harvey: The founder of the Burning Man event on adoption, uncontrollable rage - and how Freud became a father figure". The Independent.

- ^ "My Brother Larry". Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ "Parkrose High (PHS) Class of 1966 Alumni List". Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ Whiting, Sam. "Larry Harvey, founder and leader of Burning Man, dies in SF", SFGATE.com, April 30, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ Rogers, John; Har, Janie. "Burning Man festival co-founder Larry Harvey dead at 70, had ties to Portland". KGW-TV. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021.

- ^ "Larry Harvey Obituary (1948 - 2018) - San Francisco, CA - The Oregonian". Legacy.com. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ "The Jackrabbit Speaks: Volume #7 Issue #6". burningman.org. BURNING MAN PROJECT. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

In the spring of 2002, Larry Harvey and several Burning Man staff members visited New York City, where Larry delivered a speech at Cooper Union...

- ^ "Second Int'l Harvard Conference on Internet & Society". cyber.harvard.edu. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ "Larry Harvey: Burning Man, A Conversation with the Founder (7/19/11)". www.commonwealthclub.org. July 20, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ "Burning Man founder Larry Harvey in critical condition after massive stroke". San Francisco Gate. April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Burning Man founder Larry Harvey dies after massive stroke". USA TODAY. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Burning Man 2016 Financial Highlights

- Biography of Larry Harvey

- Speeches and Lectures by Larry Harvey

- Zpub - Larry Harvey quotes Archived 2018-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Larry Harvey addresses 2007 Burning Man controversy

- Larry Harvey talks about 2007 Burning Man aka Green Man

- BURNcast - Talk with Black Rock City LLC principles: Larry Harvey, Maid Marian and Danger Ranger

- The First Year in the Desert, by Louis Brill

- ABC News Video: "See What Burning Man Was Like in the 90’s," Archived 2016-09-20 at the Wayback Machine interview with Larry Harvey