Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of bridge failures

View on Wikipedia

This is a list of bridge failures.

Before 1800

[edit]| Bridge | Location | Country | Date | Construction type, use of bridge | Reason | Casualties | Damage | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milvian Bridge |

Rome | Rome | 28 October 312 | Wooden pontoon bridge replacing permanent stone bridge | Use by retreating Maxentian troops during the Battle of the Milvian Bridge | Unknown | Bridge unusable | |

| London Bridge |

London | England | 17 October 1091 | Wooden bridge | London tornado of 1091 | Unknown | Bridge unusable | |

| Sint Servaasbrug | Maastricht | Holy Roman Empire | 1275 | Wooden bridge | Collapsed from the weight of a large procession | 400 | Bridge unusable | |

| Judith bridge | Prague | Kingdom of Bohemia | 2 February 1342 | Stone bridge | Severe flood | Unknown | Two-thirds of the 170 years old bridge collapsed or heavily damaged. One arch survived to this day. Charles Bridge was built next to its remains. Construction started in 1357 and ended in 1402.[1] |  |

| Rialto Bridge |

Venice | Venetian Republic | 1444 | Wooden structure with central drawbridge. | Overload by spectators during a wedding | Unknown | Bridge total damage |

1800–1899

[edit]| Bridge | Location | Country | Date | Construction type, use of bridge | Reason | Casualties | Damage | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eitai Bridge (Eitai-bashi) | Tokyo (Edo) | Japan | 20 September 1807 (Lunisolar 19 August) | Wooden beam bridge over River Sumida | Overloaded by festival | 500–2000 killed | 1 pier and 2 spans destroyed | Edo-Tokyo Museum |

| Ponte das Barcas | Porto | Portugal | 29 March 1809 | Wooden pontoon bridge over River Douro | Bridge overloaded by thousands of people fleeing a bayonet charge of French Imperial Army led by Marshal Soult during the First Battle of Porto | 4000 killed | Several spans destroyed. Bridge reconstructed, dismantled in 1843 | [1] |

| Saalebrücke bei Mönchen-Nienburg | Nienburg, Saxony-Anhalt | Germany | 6 December 1825 | Chain-stayed bridge with small bascule section | Poor materials, unbalanced load and vibrations by subjects singing to honour the duke | 55 drowned or frozen to death | Bridge half damaged, other side demolished | [2] |

| Broughton Suspension Bridge | Broughton, Greater Manchester | England | 12 April 1831 | Suspension bridge over River Irwell | Bolt snapped due to mechanical resonance caused by marching soldiers | 0 dead, 20 injured | Collapsed at one end, bridge quickly rebuilt and strengthened |  |

| Yarmouth suspension bridge | Great Yarmouth | England | 2 May 1845 | Suspension bridge | Spectators crowded the bridge over the River Bure to view a clown travel the river in a barrel. Their position shifted as the barrel passed; the suspension chains snapped and the bridge deck tipped over. | 79 people drowned, mainly children.[3] | Suspension chains snapped due to overload. |  |

| Dee Bridge | Chester | England | 24 May 1847 | Cast iron beam bridge over the River Dee | Overload by passenger train on faulty structure | 5 killed | Bridge rendered unusable[4] |  |

| Ness Bridge | Inverness | Scotland | 1849 | Stone Bridge over River Ness | Flooding overwhelmed the 164-year-old bridge | Unknown | Either completely destroyed or damaged beyond repair[5] | Rebuilt as a suspension bridge, which itself was replaced in 1961 due to inability to handle increased traffic.[5] |

| Angers Bridge | Angers | France | 16 April 1850 | Suspension bridge over Maine River | Wind and possibly resonance of soldiers led to collapse | 226 killed, unknown injured | Bridge total damage |  |

| Wheeling Suspension Bridge | Wheeling, West Virginia (then Virginia) | United States | 17 May 1854 | Suspension bridge carrying the National Road over the Ohio River | Torsional movement and vertical undulations caused by wind | No casualties | Deck destroyed; towers left intact and remain in use today | |

| Gasconade Bridge | Gasconade, Missouri | United States | 1 November 1855 | Wooden rail bridge | Inaugural train run conducted before temporary trestle work was replaced by permanent structure | 31 killed, hundreds injured | Span from anchorage to first pier destroyed | |

| Desjardins Canal Bridge | Dundas, Ontario | Canada | 12 March 1857 | Rail bridge | Mechanical force due to broken locomotive front axle. Desjardins Canal disaster ensued. | 59 killed | [6] | |

| Sauquoit Creek Bridge | Whitesboro, New York | United States | 11 May 1858 | Railroad trestle | Weight (two trains on the same trestle) | 9 killed, 55 injured | [7][8][9] | |

| Springbrook Bridge | Between Mishawaka and South Bend, Indiana | United States | 27 June 1859 | Railroad embankment bridge | Washout | 41 killed (some accounts of 60 to 70) |  | |

| Bull Bridge | Ambergate | England | 26 September 1860 | Cast iron rail bridge | Cast iron beam cracked and failed under weight of freight train | 0 killed 0 injured | Total collapse of bridge |  |

| Wootton Bridge | Wootton | England | 11 June 1861 | Cast iron rail bridge | Cast iron beams cracked and failed | 2 killed | Total damage to floor |  |

| Platte Bridge | St. Joseph, Missouri | United States | 3 September 1861 | Sabotage by Confederate partisans during US Civil War. | 17–20 killed, 100 injured | |||

| Chunky Creek Bridge | near Hickory, Mississippi | United States | 1863 | Winter flood caused a debris build-up which shifted the bridge trestle. | ||||

| Train bridge | Wood River Junction, RI | United States | 19 April 1873 | Washaway[10][11] | 7 killed, 20 injured |  | ||

| Dixon Bridge (aka Truesdell Bridge) | Dixon, Illinois | United States | 4 May 1873 | Iron vehicular bridge (for pedestrians and carriages) over the Rock River | Large crowd assembled on one side to view baptism ceremony; bridge design flaw | 46 killed 56 injured | Bridge was a total loss |  |

| Portage Bridge | Portageville, New York | United States | 5 May 1875 | Wooden beam bridge over the Genesee River | Fire | 0 killed 0 injured | Bridge was a total loss |  |

| Ashtabula River Railroad Bridge | Ashtabula, Ohio | United States | 29 December 1876 | Wrought iron truss bridge | Possible fatigue failure of cast iron elements | 92 killed, 64 injured | Bridge total damage |  |

| Tay Rail Bridge | Dundee | Scotland | 28 December 1879 | Continuous girder bridge, wrought iron framework on cast iron columns, railway bridge | Faulty design, construction and maintenance, structural deterioration and wind load | 75 killed (60 known dead), no survivors | Bridge unusable, girders partly reused, train damaged |  |

| Honey Creek Rail Trestle | Boone County, Iowa | United States | 6 July 1881 | Railroad trestle | Flash flood washed out timbers supporting trestle | 2 killed (one body never recovered) | Bridge rebuilt | Kate Shelley, who lived nearby, was able to warn the railroad to stop an oncoming passenger train. |

| Inverythan Rail Bridge | Aberdeenshire | Scotland | 27 November 1882 | Cast iron girder rail bridge | Hidden defects in cast iron caused collapse as train passed | 5 killed, 17 injured | Bridge rebuilt |  |

| Little Silver | New Jersey | United States | 30 June 1882 | Trestle railway bridge | Train derailment due to insecure railroad switch on the northbound side of the bridge. | 3 killed, 65+ injured | Estimated $15,000 worth of damage to the bridge and cars combined. Bridge was repaired. | Several rail cars derailed and fell off the bridge into Parker's Creek. Ulysses S. Grant was a passenger.[12] |

| Osijek railway bridge | Osijek | Hungary / Croatia border | 23 September 1882 | Railway bridge | Bridge collapsed into the flooding Drava river under the weight of a train | 28 | Washout by flood Collapsed wooden bridge later replaced by iron bridge. |

[13][14] |

| Camberwell Bridge | London | England | 15 May 1884 | Cast iron trough girder bridge over railway | Hidden defects in cast iron caused collapse of four girders | 0 killed, 1 injured | Bridge rebuilt | |

| Bussey Bridge | Boston | United States | 14 March 1887 | Iron railroad bridge collapses under train | Poor design and maintenance[15] | 23 killed, 100+ injured | Bridge rebuilt |  |

| Big Four Bridge | Louisville, Kentucky | United States | 10 October 1888 | Caisson and truss | 12 died when caisson flooded,

4 died when beam broke, |

|||

| Conemaugh Viaduct | Upriver from Johnstown, Pennsylvania | United States | 31 May 1889 | Stone,78-foot (24 m) high railroad bridge | Washed away by the Johnstown Flood | 0 | total loss | |

| Norwood Junction Rail Bridge | London | England | 1 May 1891 | Cast iron girder fails under passing train | Hidden defects in cast iron caused collapse | 0 killed, 1 injured | Bridge rebuilt | |

| Münchenstein Rail Bridge | Münchenstein | Switzerland | 14 June 1891 | Wrought iron truss | Train falls through centre of bridge | 71 killed, 171 injured |  | |

| Chester rail bridge | Chester, Massachusetts | United States | 31 August 1893 | Lattice truss bridge | Removed rivets caused bridge to collapse under the weight of a train | 14 killed | ||

| Point Ellice Bridge | Victoria, British Columbia | Canada | 26 May 1896 | Overloaded tram car collapses central span | 47/53/50–60 killed (reports vary) | |||

| Maddur railway bridge collapse | Maddur | India | 2 October 1897 | River in flood | 150 drowned | AA | [16] |

1900–1949

[edit]| Bridge | Location | Country | Date | Construction type, use of bridge | Reason | Casualties | Damage | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Creek Bridge | Eden, Colorado | United States | 7 August 1904 | Wooden railway bridge | Collapsed because of a sudden washout | 111 killed, unknown injured | Bridge completely destroyed | |

| Egyptian Bridge | Saint Petersburg | Russian Empire | 20 January 1905 | Stone suspension bridge | Disputed | 0 killed, 0 injured | Bridge rebuilt |  |

| Portage Canal Swing Bridge | Houghton, Michigan | United States | 15 April 1905 | Steel swing bridge | Swing span struck by the steamer Northern Wave. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Swing span rebuilt. |  |

| Cimarron River Rail Crossing | Dover, Oklahoma Territory | United States | 18 September 1906 | Wooden railroad trestle | Washed out under pressure from debris during high water | 4-100+ killed | Entire span lost; rebuilt | Bridge was to be temporary, but replacement was delayed for financial reasons.[17][18][19] Number of deaths is uncertain; estimates range from 4 to over 100.[20] |

| Quebec Bridge | Quebec City | Canada | 29 August 1907 | Cantilever bridge, steel framework, railway bridge | Collapsed during construction: design error, bridge unable to support own weight | 75 killed, 11 injured | Bridge completely destroyed. |  |

| Romanov Bridge | now Zelenodolsk, Republic of Tatarstan | Russian Empire | 22 November 1911 | Railway bridge across the Volga River | Collapsed during construction: ice slip undermined scaffolding | 13 confirmed killed, ~200 missing | Scaffold with workers fell on the ice, causing many to drown | Bridge was completed later. "Romanovsky" rail bridge, renamed Red Bridge after the revolution, designed by Nikolai Belelubsky was built in 1913. |

| Baddengorm Burn | Carrbridge, Highlands | Scotland | 18 June 1914 | Collapsed underneath train due to heavy rainfall and debris build-up from a road bridge wiped out further upstream | 5 drowned, unknown injured | Complete loss, one railway carriage destroyed | Rebuilt with a longer, concrete span. | |

| Division Street Bridge | Spokane, Washington | United States | 18 December 1915 | Steel framework, trolley car bridge | Collapsed a week after being resurfaced; poor steel, metal fatigue, and a previous impact by another bridge swept downstream during a flood | 5–7 killed, 10 injured | Complete loss, plus two trolley cars destroyed | Replaced by a 3-vault concrete span |

| Quebec Bridge | Quebec City | Canada | 11 September 1916 | Cantilever bridge, steel framework, railway bridge | Central span slipped whilst being hoisted in place due to contractor error | 11 killed, unknown injured | Central span dropped into the river, where it still lies today | Rebuilt and opened in December 1919 after almost two decades of construction. |

| Grand Avenue Bridge | Neillsville, Wisconsin | United States | 2 August 1920 | Steel overhead truss bridge, vehicular traffic | Believed to have been weakened by heavy trucks hauling shale crossing the bridge in prior months | 1 killed, 0 injured | Bridge completely destroyed. | Replaced by concrete bridge the following year.[21][22] |

| Greenfield Bridge | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | United States | 18 June 1921 | Wooden road bridge | Collapsed | 0 killed, 0 injured | Bridge completely destroyed | Bridge had been closed to vehicular traffic due to structural weakness but was still used by pedestrians.[23] Replaced with a new bridge in 1923. |

| Bridge | Jalón | Spain | 22 November 1927 | Bridge failed during passage of funeral procession | 100 thrown into water | [24] | ||

| Kärevere Bridge | Kärevere | Estonia | 14 December 1928 | 48 m triple span beam bridge with reinforced concrete deck, motorway bridge over the Suur-Emajõgi river | Newly built bridge failed two days after commission accepted it (before opening for traffic), because of too small share of cement in concrete and some serious design flaws | No casualties. | Bridge completely destroyed. | [25] |

| Fremantle Railway Bridge | Fremantle, Western Australia | Australia | 22 July 1926 | Flood | 0 killed, 0 injured |  Proposed replacement by combined road and railway bridge.[27][needs update] | ||

| Seta River Bridge | Otsu | Japan | 21 September 1934 | Typhoon | 11 killed, 216 injured |  | ||

| Appomattox River Drawbridge | Hopewell, Virginia | United States | 22 December 1935 | Bus drove across the drawbridge when it was open. | 14 killed | |||

| Falling Creek Bridge | Chesterfield County, Virginia | United States | 1 September 1936 | Wood and steel. | Two trucks were crossing the bridge when one struck a tie rod causing the bridge to collapse. One truck fell 15 feet to the creek bed, and the other escaped to safety. | 4 killed, 5 injured | [28] | |

| Kasai River Bridge | Kasaï | Belgian Congo | 12 September 1937 | Railway bridge | While under construction. | Began in 1935; construction never resumed. | ||

| Honeymoon Bridge (Upper Steel Arch Bridge) | Niagara Falls, New York – Niagara Falls, Ontario | United States – Canada | 27 January 1938 | Steel arch road bridge | Ice jam in gorge pushed bridge off foundations | 0 killed, 0 injured | Bridge completely destroyed |  |

| Sandö Bridge | Kramfors, Ångermanland | Sweden | 31 August 1939 | Concrete arch bridge | Collapsed during construction | 18 killed | Complete loss of the main span | Received minimal media attention as WWII began the next day. The bridge was finished in 1943 as the longest concrete arch bridge in the world until 1964. |

| Tacoma Narrows Bridge | Tacoma, Washington | United States | 7 November 1940 | Road bridge, cable suspension with plate girder deck | Aerodynamically poor design resulted in aeroelastic flutter | 0 killed, 0 injured (1 dog killed) | Bridge completely destroyed, no persons killed. One dog killed and three vehicles lost. | Became known as "Galloping Gertie", in the first 4 months after opening up until its collapse under aeroelastic flutter. Most major new bridges are now modelled in wind tunnels.

Rebuilt in 1950; parallel span opened in 2007. |

| Theodor Heuss Bridge | Ludwigshafen | Germany | 12 December 1940 | Bridge of concrete, Motorway bridge | Collapsed during construction | Unknown | Bridge completely destroyed |  |

| Chesapeake City Bridge | Chesapeake City, Maryland | United States | 28 July 1942 | Road bridge, vertical lift drawbridge | Tanker Franz Klasen rammed the movable bridge supports, causing collapse | Unknown | Central span completely destroyed | Bridge replaced by high-level tied-arch bridge in 1949 |

| Deutz Suspension Bridge | Cologne | Germany | 28 February 1945 | Suspension road bridge | collapsed during repair work | unknown count of people killed | Total destruction | |

| Ludendorff Bridge | Remagen | Germany | 17 March 1945 | Truss railroad and pedestrian bridge | Collapse due to previous battle damage incurred 7 March 1945 | 28 killed, 93 injured | Total destruction |  |

| John P. Grace Memorial Bridge | Charleston, South Carolina | United States | 24 February 1946 | Steel cantilever truss automobile bridge | Three spans collapsed due to collision by the freighter Nicaragua Victory | 5 killed | Three collapsed spans 240 feet (73 m) were replaced and stood until 2005 when the bridge was closed following the opening of the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge | |

| Inotani Wire Bridge | Toyama | Japan | 22 September 1949 | 29 killed | Around 150 professors and educators from schools in the prefecture were in the area for a geological survey when a bolt bent and the suspension bridge collapsed, sending 33 people down into the Jinzu River. 29 people were killed or went missing and 4 people were injured.[29] |

1950–1999

[edit]| Bridge | Location | Country | Date | Construction type, use of bridge | Reason | Casualties | Damage | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duplessis Bridge | Trois-Rivières–Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Quebec | Canada | 31 January 1951 | Steel bridge | Structural failure due to adverse temperature | 4 killed | Total destruction | Reconstructed |

| Bury Knowsley Street Station Footbridge | Bury | England | 19 January 1952 | Wooden footbridge with wrought iron frame and supports | Supports failed due to inadequate maintenance | 2 killed, 173 injured | Bridge replaced | Bridge since demolished, due to closure of station |

| Harrow & Wealdstone Station Footbridge | Wealdstone | England | 8 October 1952 | Pedestrian footbridge | Struck by train(s) during accident | 112 killed, 340 injured | Total destruction | It is not recorded how many casualties were due to the bridge collapse |

| Whangaehu River Rail Bridge | Tangiwai | New Zealand | 24 December 1953 | Railway bridge | Damaged by lahar minutes before passenger train passed over it. | 151 killed. New Zealand's worst train disaster. | Bridge destroyed | |

| St. Johns Station Rail Bridge | Lewisham, South London | England | 4 December 1957 | Railway bridge | Two trains collided and smashed into supports, collapsing part of bridge onto the wreckage | 90 killed, 173 injured | Bridge destroyed | Unknown how many deaths/injuries specifically due to bridge collapse, since its effect was to worsen the train wreck |

| Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing | Vancouver, British Columbia | Canada | 17 June 1958 | Steel truss cantilever | Collapsed during construction due to miscalculation of weight bearing capacity of a temporary arm. | 19 killed, 79 injured | Rebuilt | 8 additional deaths during the course of construction |

| Severn Railway Bridge | Gloucestershire | England | 25 October 1960 | Cast iron | Two of 22 spans collapsed after two petrol barges collided with one of the support columns in thick fog. A third span collapsed 5 months later. | 5 killed | Demolished 1967–1970 |  |

| I-29 Big Sioux River Bridge | Sioux City, Iowa | United States | 1 April 1962 | Plate Girder | Northbound road deck collapsed into Big Sioux River as a result of heavy flooding | Rebuilt and in current use | ||

| King Street Bridge | Melbourne, Victoria | Australia | 10 July 1962 | One span collapsed under the weight of a 47-long-ton (48 t) semi-trailer due to brittle fracture on a very cold winter day | 0 killed | |||

| Beaver Dam Bridge | approximately 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) southeast of Whitehouse, Quebec | Canada | 22 May 1963 | Flood damage | 6 killed | Several vehicles fell into the York river[30] | ||

| General Rafael Urdaneta Bridge | Maracaibo | Venezuela | 6 April 1964 | Road bridge | Ship collision | 7 killed | 2 section collapsed | Currently in operation |

| Lake Pontchartrain Causeway | Metairie, Louisiana | United States | 16 June 1964 | Ship collision | 6 killed | Single span collapse | [31] | |

| Pamban Bridge | Mandapam, Tamil Nadu | India | 23 December 1964 | Rail Bridge | 1964 Rameswaram Cyclone | Train washed away killing 150 people. | Multiple span collapsed. | Currently New Bridge under construction. |

| Kansas Avenue Bridge | Topeka, Kansas | United States | 2 July 1965 | Kansas Avenue Melan Bridge for traffic between downtown and North Topeka | Structural deterioration | 1 killed | Single span collapse | Suddenly collapsed about 5:30 p.m. on 2 July 1965, killing a Topeka man.[32] |

| Long Shoal Bridge | Benton County, Missouri | United States | 21 September 1965 | Swinging suspension road bridge | Faulty design and overload | 3 killed | Total collapse | Collapsed after a 10-ton truck crossed the bridge, which had a 5-ton limit. Old bridge remains at bottom of river.[33] |

| Heron Road Bridge | Ottawa | Canada | 10 August 1966 | Concrete road bridge | Collapsed during construction due to use of green lumber and the lack of diagonal bracing on the wooden support forms for concrete pour. | 9 killed | Rebuilt. | |

| Boudewijnsnelweg Bridge | Viersel | Belgium | 13 November 1966 | Concrete road bridge over Nete Canal (Netekanaal) | Collapse due to faulty design: the foundation of the piers was not deep enough. | 2 killed, 17 injured | Rebuilt. | |

| Heiligenstedten Bascule Bridge | Heiligenstedten | Germany | 1966 | Road bridge | Ship collision | 0 killed | Bridge rebuilt | |

| Huasco Bridge | Vallenar | Chile | 9 May 1967 | Road bridge | Unclear[34] | 8 killed, 10 injured[34] | Bridge collapsed during initial construction. Construction restarted in 1972; bridge opened in 1977.[34] | |

| Silver Bridge | Point Pleasant, West Virginia and Gallipolis, Ohio | United States | 15 December 1967 | Road bridge, chain link suspension | Stress corrosion cracking; nonredundant eyebar design | 46 killed, 9 injured | Bridge and 37 vehicles destroyed. Replaced by Silver Memorial Bridge downstream. Memorial for bridge located on 6th and Main Streets and off the trail along the shoreline in Point Pleasant. |  |

| Queen Juliana Bridge | Willemstad, Curaçao | Netherlands Antilles | 6 November 1967 | Portal bridge | Construction support fault. Bridge fell during construction | 15 killed | Bridge collapsed at the Punda side | Bridge reconstruction started in 1969 and was completed in 1971 |

| Countess Wear Bridge | Exeter, Devon | England | 6 January 1968 | Brick Arch bridge | Construction support fault. Scour under raft foundation | Pier 23 collapsed | Bridge repaired and reinforced | |

| Britannia Bridge | Menai Strait | Wales | 23 May 1970 | Railway tubular bridge | Children accidentally set light to debris and railway sleepers and irreparably damaged the bridge | No casualties | Tubular section buckled beyond repair | Bridge re-built to a new design using the original piers with a road deck over the new railway deck |

| West Gate Bridge | Melbourne, Victoria | Australia | 15 October 1970 | Road bridge | Collapsed during construction due to poor design and ill-advised construction methods | 35 killed | 112-metre (367 ft) span between piers 10 and 11 collapsed | Cantilevered section under construction sprang back and collapsed following attempts to remove a buckle caused by a difference in camber of 11 cm (4.5 inches) between it and the other section of the span to which it was to be joined |

| Cleddau Bridge | Pembroke Dock and Neyland | Wales | 2 June 1970 | Box girder road bridge | Inadequacy of the design of a pier support diaphragm | 4 killed, 5 injured | 70-metre (230 ft) cantilever being used to put one of the 150-tonne (150-long-ton) sections into position collapsed | |

| South Bridge, Koblenz | Koblenz | Germany | 10 November 1971 | Road bridge | Bridge bent into Rhine | 13 killed, unknown injured | Bridge completely destroyed | |

| Charles III Bridge | Molins de Rei | Spain | 6 December 1971 | Stone road bridge | Flood damage | 1 killed | 2 arches collapsed, a lorry fell into the Llobregat | Prior to the accident, dredging of the riverbed to mine sand had weakened pier foundations. The bridge was finally blown up and a new one built in its place. |

| Fiskebækbroen | Farum | Denmark | 8 February 1972 | Two separate highway bridges of the E45 highway | Western bridge collapsed during construction as the concrete for the foundation was not adequately compressed | None injured | Bridge rebuilt | The involved construction company C.T. Winkel, subsequently went bankrupt.[citation needed] |

| 1972 Sidney Lanier Bridge collapse | Brunswick, Georgia | United States | 7 November 1972 | Vertical Lift Bridge over the South Brunswick River | Struck by the freighter African Neptune | 10 deaths, multiple injuries | Several spans knocked out | Repaired during 1972–73 then completely replaced with a new cable-stayed bridge in 2003 |

| Bulls Bridge | Bulls | New Zealand | 15 June 1973 | Flood damage | 1 injured | 3 spans collapsed | A Bailey Bridge was in place over the gap within 6 weeks and a full replacement of the three spans was opened in December 1973. | |

| West Side Elevated Highway | New York City | United States | 15 December 1973 | Poor maintenance and overloading | No casualties | Single span collapse, which caused the closure and eventual demolition of most of the highway. |  | |

| Welland Canal Bridge No. 12 | Port Robinson, Ontario | Canada | 25 August 1974 | Vertical lift bridge over the Welland Canal | Struck by the ore carrier Steelton | 0 killed, 2 injured | Bridge declared a loss; new tunnel or bridge rebuilding costs were found to be unjustified. |  |

| Makahali River bridge | Baitadi | Nepal | November 1974 | 140 killed | ||||

| Tasman Bridge | Hobart, Tasmania | Australia | 5 January 1975 | Bridge of concrete, Motorway bridge | Ore freighter Lake Illawarra collided with pylons. A 400-foot (120 m) section of bridge collapsed onto freighter and into the river. Four cars drove off bridge | 12 killed (7 ship crewman and 5 motorists) | 2 pylons and three sections of bridge collapsed, ore freighter sank, 4 cars fell into river | City of Hobart was split in two. Residents living in the east were forced to make a 50 kilometres (31 mi) trip to the CBD via the next bridge to the north. Missing sections were reconstructed and the bridge reopened on 8 October 1977. The Bowen Bridge was later constructed, 10 km (6 mi) to the north, to reduce the impact of any future failure of the Tasman Bridge. |

| Reichsbrücke | Vienna | Austria | 1 August 1976 | Road bridge with tram | Column fractured | 1 killed, 0 injured | Bridge, one bus and a lorry destroyed, ships damaged |  |

| Granville Railway Bridge | Sydney, New South Wales | Australia | 18 January 1977 | Vehicle overpass | Passenger train derailed while passing under the Bold Street road overpass and collided with a supporting pier. Section of bridge collapsed onto train cars. | 83 (including an unborn child) killed, 210 injured | Bridge destroyed, later replaced | The bridge was supported by two piers situated between the various rail tracks. Part of the derailed train virtually demolished the northern pier, resulting in the collapse of the northernmost span of the bridge. It was replaced by a single-span bridge. |

| Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge | Hopewell, Virginia | United States | 24 February 1977 | Lift bridge | An ocean-going tanker ship, the 5,700 ton, 523-ft long Marine Floridian struck the bridge collapsing a section of the bridge. | 0 killed, minor injuries | Section of bridge destroyed | Bridge repaired |

| Green Island Bridge | Troy, New York | United States | 15 March 1977 | Lift bridge | Flooding undermined the lift span pier resulting in the western lift tower and roadbed span of the bridge collapsing into the Hudson River. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Bridge destroyed | |

| Floating bridge over Beloslav Canal (connecting Lake Beloslav and Lake Varna)[36] | Beloslav, Varna Province | Bulgaria | 7 November 1978 | Floating bridge | Overload by spectators | 65 killed | Bridge completely destroyed | |

| Hood Canal Floating Bridge (William A. Bugge Bridge) | North End of Hood Canal, Washington | United States | 13 February 1979 | Floating bridge | Blown pontoon hatches combined with extreme windstorm | 0 killed, 0 injured | Western drawspan and western pontoons sunk; other sections survived. | Lost portions rebuilt 1979–1982; the remainder of the bridge has since been replaced. |

| Almöbron (Tjörnbron) | Stenungsund | Sweden | 18 January 1980 | Steel arch bridge | Ship collision during bad visibility (mist) | 8 killed, unknown injured | Bridge and several cars destroyed |  |

| Sunshine Skyway Bridge | near St. Petersburg, Florida | United States | 9 May 1980 | Steel cantilever bridge | The freighter Summit Venture struck the bridge during a storm, causing the center section of the southbound span to collapse into Tampa Bay | 35 killed, 1 injured | 1,200 feet (370 m) of southbound span, several cars and a bus destroyed | A vehicle stopped just short of the collapsed portion of the bridge. The old bridge has since been turned into a state-run fishing pier and was replaced for traffic with cable-stayed bridge. |

| Tompkins Hill Road overpass[37] | Humboldt County, California | United States | 8 November 1980 | Reinforced concrete spans on concrete support columns | Earthquake caused two spans to slip off supporting columns | 0 killed, 6 injured | Two vehicles drove into the opening left by collapsed span | Steel cables added to anchor replacement spans to support columns |

| Hyatt Regency walkway collapse | Kansas City, Missouri | United States | 17 July 1981 | Double-deck suspended footbridge in hotel interior | Erroneous redesign of supporting member during construction when original design considered too hard to construct | 114 killed, 200 injured | Walkway destroyed |  |

| Cline Avenue over the Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal and surrounding heavy industry | East Chicago, Indiana | United States | 15 April 1982 | Indiana State Route 912 | 1,200 feet (370 m) of the bridge collapsed while under construction when a concrete pad supporting shoring towers developed cracks. | 14 killed, 16 injured | Bridge rebuilt | Section between US 12 and the Indiana Toll Road renamed Highway Construction Workers Memorial Highway |

| Puente de Brenes | Brenes, Sevilla | Spain | 12 Aug 1982 | Carretera Brenes-Villaverde del Rio | Structural failure due to inadequate design | No casualties | The bridge collapsed during the night | |

| Ulyanovsk railway bridge | Ulyanovsk | USSR | 5 June 1983 | Railway bridge | Ship collision | 177 killed, unknown injured | No collapse | The span cut the deck house and the cinema hall, whilst the lowest deck was undamaged. The ship damaged the railway bridge and some freight cars from the train fell onto the ship. |

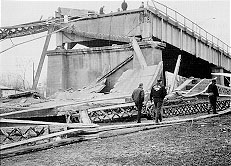

| Mianus River Bridge | Greenwich, Connecticut | United States | 28 June 1983 | Interstate 95 (Connecticut Turnpike) over the Mianus River | Metal corrosion and fatigue/Deferred maintenance | 3 killed, 3 injured[38] | 100-foot (30 m) section of the northbound lanes fell into the Mianus River | Collapse due to failure of the pin and hanger assembly supporting the span. Temporary span installed to re-open I-95; new Mianus River Bridge completed in 1990. |

| Puente Colgante de Santa Fe | Santa Fe | Argentina | 28 September 1983 | Suspension Bridge | Flooding | 0 killed, 0 injured | Total collapse |  |

| Cuscatlán Bridge | San Ildefonso | El Salvador | 1 January 1984 | Suspension bridge | Bombing | Several killed | Total collapse |  |

| U.S. Highway 36, the Boulder Turnpike, near MP 12.5 | Westminster, Colorado | United States | 2 August 1985 | Concrete bed with steel girders on concrete support posts | Head-on Train Collision | 5 killed | Northbound span collapsed in accident; southbound span collapsed during cleanup efforts. Within days, crews built a temporary road around the scene of the accident and erected a stoplight at the tracks, and the bridge was eventually rebuilt. |  |

| Stebbins Rd. Bridge (NY State Rt 90, not to be confused with Interstate 90) | Hanover, NY | United States | 15 November 1986 | One lane steel bridge | Likely overloaded | 1 killed, 3 injured | Total loss | Collapse likely due to overloading. The bridge, with a posted 8-ton limit, was crossed by a construction crane.[39] |

| Amarube railroad bridge | Kasumi, Hyōgo | Japan | 28 December 1986 | Strong wind | 6 killed (one train conductor and five factory workers) | An out-of-service train fell onto a fish processing factory | ||

| Schoharie Creek Bridge collapse Thruway Bridge | Fort Hunter, New York | United States | 5 April 1987 | I-90 New York Thruway over the Schoharie Creek | Improper protection of footings by contractor led to scour of riverbed under footings. | 10 killed, unknown injured | Total collapse | [40] |

| Schoharie Creek's Mill Point Bridge | Wellsville, Amsterdam, New York | United States | 11 April 1987 | NY 161 over the Schoharie Creek | Flooding | 0 killed, 0 injured | Total collapse | The Mill Point Bridge is 3 miles (4.8 km) upstream from the Thruway bridge that collapsed on 5 April. Flood waters from the same flood that finally undermined the Thruway bridge were up to the girders of the Mill Point bridge. It was closed as a safety precaution. It collapsed six days after the earlier collapse.[41] |

| Glanrhyd Bridge | Carmarthen | Wales | 19 October 1987 | River Tywi | Train washed off railway bridge by flood waters | 4 killed | ||

| Sultan Abdul Halim ferry terminal bridge | Butterworth, Penang | Malaysia | 31 July 1988 | More than 32 killed.[42] | ||||

| Ness Viaduct | Inverness | Scotland | 7 February 1989 | Railway bridge carrying the Far North Line over the River Ness | Bridge foundations overwhelmed by floodwaters due to low tide in Beauly Firth causing waterfall effect | 0 killed, 0 injured | Near total collapse, remains demolished and rebuilt in 1990 | Bridge confirmed to be structurally sound in 1987 and 1988 checks |

| Tennessee Hatchie River Bridge | Between Covington, Tennessee and Henning, Tennessee | United States | 1 April 1989 | Northbound lanes of U.S. 51 over the Hatchie River | Shifting river channel, deterioration of foundation timber piles | 8 killed | Total collapse | NTSB faulted Tennessee for not fixing the bridge before the collapse |

| Cypress Street Viaduct | Oakland, California | United States | 17 October 1989 | I-880 (Nimitz Freeway) | Destroyed in Loma Prieta earthquake | 42 killed | Structure destroyed, remains demolished and removed. The ground-level Cypress Street is now Mandela Parkway. |  |

| San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge | connects San Francisco and Oakland, California | United States | 17 October 1989 | I-80 | 50-foot (15 m) section of the upper deck and lower deck collapsed in Loma Prieta earthquake | 1 killed |  Reopened on 18 November of that year. Replaced with a self-anchored suspension bridge and approach spans in 2013. | |

| Swinging Bridge | Heber Springs, Arkansas | United States | 28 October 1989 | Pedestrian suspension bridge over the Little Red River; 1912 erected but 1972 closed for cars; 1985 placed in National Register of Historic Places | Destroyed by pedestrians swinging the bridge | at least 5 killed[43] | Structure collapsed | |

| Lacey V. Murrow Memorial Bridge | Connects Seattle and Mercer Island, Washington | United States | 25 November 1990 | I-90 | Heavy flooding of pontoons | 0 killed 0 injured | 2,790 feet (850 m) of the bridge sank, dumping the contaminated water into the lake along with tons of bridge material | |

| Astram Line steel bridge | Hiroshima | Japan | 1991 | Metro railway | While in construction, 43-ton steel fell to the road below. | 15 killed (5 workers and 10 civilians), 8 injured | ||

| Santa Monica Freeway at La Cienega Boulevard | Mid City, Los Angeles | United States | 17 Jan 1994 | 1994 Northridge Earthquake |  | |||

| Newhall Pass Interchange | Newhall, Santa Clarita, California | United States | 17 Jan 1994 | 1994 Northridge Earthquake | 1 killed |  | ||

| Claiborne Avenue Bridge | 9th Ward, New Orleans, Louisiana | United States | 28 May 1993 | Bridge connecting the "upper" and "lower" 9th Wards | Barge collision | 1 killed, 2 injured | Empty barge collided with a support pier for the bridge, causing a 145-foot (44 m) section to collapse | |

| Kapellbrücke (Chapel Bridge) | Lucerne | Switzerland | 18 August 1993 | The oldest wooden bridge in Europe, and one of Switzerland's main tourist attractions. | It is believed that a cigarette started a fire in the evening. | 0 killed, unknown injured | 78 of 111 of the famous paintings were destroyed and the bridge burned nearly completely down. The bridge was rebuilt to match the original. | |

| CSXT Big Bayou Canot rail bridge | near Mobile, Alabama | United States | 22 September 1993 | Railroad bridge span crossing Big Bayou Canot of Mobile River | Barge towboat, struck pier in fog; span shifted so next train derailed; impact of derailment destroyed span | 47 killed, 103 injured | Amtrak train Sunset Limited carrying 220 passengers plunged into water | Bridge span had been made movable in case a swing bridge was wanted, and never properly fastened |

| Temporary bridge | Hopkinton, New Hampshire | United States | 24 November 1993 | Single-lane temporary bridge in construction zone | Collapsed while being dismantled | 2 construction workers killed, 1 injured | Collapsed onto roadway below | Bridge had been placed to divert traffic from resurfacing project on U.S. Route 202 |

| Seongsu Bridge disaster | Seoul | South Korea | 21 October 1994 | Cantilever bridge crossing Han River | Structural failure due to bad welding | 32 killed, 17 injured | 48-metre (157 ft) slab between the fifth and the sixth piers collapsed |  |

| Kobe Route of the Hanshin Expressway | Kobe, Japan | Japan | 17 January 1995 | Elevated highway | Earthquake - support piers failed | 0 killed. 0 injured | Section collapsed on the Hanshin Expressway. | Overpass collapsed following the 6.9 Mw Great Hanshin earthquake. |

| I-5 Bridge Disaster | Coalinga, California | United States | 10 March 1995 | Concrete truss bridge Arroyo Pasajero | Structural failure — support piers collapsed | 7 killed, 0 injured | Complete failure of two spans on I-5 | Due to extreme rainfall, the Arroyo Pasajero experienced high volumes of water at high speed. This caused scouring of the river bed undermining the support piers of both spans. |

| Elhovo bridge over the Tundzha river[44] | Elhovo, Yambol Province | Bulgaria | 6 January 1996 | Suspension bridge | Over 100 spectators crowded on one side of the bridge to observe the throwing of the cross (an Epiphany tradition) into the river when one of the suspension chains snapped and dozens fell into the icy river. | 9 killed | Suspension chain snapped due to overload. | |

| Walnut Street Bridge | Harrisburg, Pennsylvania | United States | January 1996 | Truss bridge | As a result of rising flood waters and ice floes from the North American blizzard of 1996, when high floodwaters and a large ice floe lifted the spans off their foundations and swept them down the river. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Lost two of its seven western spans, A third span was damaged and later collapsed into the river. |  |

| Koror-Babeldaob Bridge | Koror and Babeldaob | Palau | 26 September 1996 | Collapse following strengthening work | 2 killed, 4 injured | |||

| Maccabiah bridge collapse | Tel Aviv/Ramat Gan border | Israel | 14 July 1997 | Athletes pedestrian bridge | Poor design and construction | 4 killed (2 killed in collapse, 2 others indirectly), 60 injured | During opening of the 15th Maccabiah Games, a temporary bridge over the polluted Yarkon River collapsed causing two deaths the same day and infected many with the deadly fungus Pseudallescheria boydii, from which 2 more died later. | |

| Eschede train disaster | Eschede | Germany | 3 June 1998 | Road bridge | Train disaster | 101 killed, 105 injured | After derailing due to metal fatigue in one of its metal tyres, the Hanover-bound InterCityExpress high speed train collided with a road bridge, causing it to collapse onto part of the train. 99 people on board the train, as well as two engineers who were working near the track at the time of the accident, were killed. | |

| Injaka Bridge Collapse | Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga | South Africa | 6 July 1998 | 300m 7-span continuous pre-stressed concrete road bridge over the Injaka Dam under construction. | Design faults and negligence.[45] | 14 killed, 19 injured | Structure destroyed. Rebuilt completed in 2000, now carrying the R533 over the Injaka Dam (Reservoir). | Collapsed while being inspected. Victims include design and consulting engineers. |

| Qijiang Rainbow Bridge Collapse | Qijiang, Chongqing | People's Republic of China | 4 Jan 1999 | Pedestrian arch bridge | Shoddy materials and workmanship due to corrupt officials | At least 40 killed, 14 injured[46] | Total destruction | Collapsed 3 years after construction was finished in 1996. Multiple people involved with the bridge's construction were arrested and tried, with at least one sentenced to death.[47] The bridge was rebuilt in 2000. |

| Maiden Choice Footbridge[48] | Arbutus, Baltimore County, Maryland | United States | 8 June 1999[49][50] | Pre-stressed concrete pedestrian footbridge | Collision with overheight road vehicle.[49][50] | 1 killed, 6 injured[49][50] | The entire footbridge, the surviving span and the fallen span, were demolished overnight and removed by the next morning.[49][50] | Collapsed after being struck by an over-height and improperly secured load on a flatbed tractor-trailer.[51][52]

The entire structure - which was built in 1957 - had been closed for two years.[49][50][needs update] |

2000–2020

[edit]| Bridge | Location | Country | Date | Construction type, use of bridge | Reason | Casualties | Damage | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlotte Motor Speedway pedestrian bridge over U.S. Route 29 | Charlotte, North Carolina | United States | 20 May 2000 | Concrete pedestrian bridge | Beam weakness and other unspecified reasons. | 0 killed, 107 injured | Partial collapse | Collapsed after the 2000 NASCAR All-Star Race while full of pedestrians leaving the event. The bridge fell onto U.S. Route 29. |

| New Magarola Bridge | Esparreguera | Spain | 10 June 2000 | Concrete road bridge | 2 killed | Partial collapse |  | |

| Boulevard du Souvenir overpass collapse | Laval, Quebec | Canada | 18 June 2000 | Steel beams and concrete | Beam weakness and other unspecified reasons. | 1 killed, 2 injured | Total collapse | Collapsed onto the road below, killing 1 person and injuring 2 others. Remainder was demolished after the collapse by authorities for safety reasons. |

| Chagres River | Gamboa | Panama | 23 June 2000 | 0 killed, 0 injured | Bulk carrier "Bluebill" hit railway bridge crossing river, severely damaging the bridge and severing railway midway between the terminals. | |||

| Hoan Bridge | Milwaukee, Wisconsin | United States | 13 December 2000 | Concrete and steel bridge | Northbound right lane began to buckle during the morning rush hour and sagged a few feet below normal. Damage was a result of a violent failure of cross bracing members caused by extremely high stress concentrations in triaxial welds. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Partial collapse | Damaged section removed by controlled demolition and rebuilt. Remainder of bridge extensively repaired and retrofitted. Triaxial welds were drilled and most cross bracing members were removed. Many other similar bridges around the world were also modified in this way as a result of this failure. |

| Hintze Ribeiro Bridge | Entre-os-Rios, Castelo de Paiva | Portugal | 4 March 2001 | Masonry and steel bridge built in 1887 | Pillar foundation became compromised due to years of illegal, but permitted sand extraction and the central span collapsed. | 59 killed | Collapse of central sections |  |

| I-285 bridge over GA-400 | Atlanta, Georgia | United States | 9 June 2001 | Concrete and steel bridge | A fuel tanker overturned underneath the bridge, engulfing the bridge in fire | 0 killed, 1 injured | Structural damage required closure of the bridge | Reopened after four week repair[53][54] |

| Kadalundi River rail bridge | Kadalundi | India | 21 June 2001 | 140-year-old rail bridge | 59 killed, 200 injured[55][56] | Collapsed as a Mangalore Mail passenger train was crossing it, six carriages derailed and three went into the river[55] | ||

| Queen Isabella Causeway | Port Isabel, Texas and South Padre Island, Texas | United States | 15 September 2001 | Concrete bridge for vehicle traffic over Laguna Madre | 4 loaded barges veered 175 feet (53 m) west of the navigation channel and struck one of the bridge supports, causing a partial collapse of 3 sections measuring approximately 80 feet (24 m) each. | 8 killed, 13 survivors | Partial collapse |  The collapse had a significant economic impact on the region since the Causeway is the only road connecting South Padre Island to Port Isabel. The bridge also carried electricity lines and fresh water to the island. State officials brought in ferries to temporarily carry cars across the Laguna Madre. Repair cost for the bridge was estimated US$5 million. |

| I-40 bridge disaster | Webbers Falls, Oklahoma | United States | 26 May 2002 | Concrete bridge for vehicle traffic over Arkansas River | Barge struck one pier of the bridge causing a partial collapse | 14 killed, 11 injured | Partial collapse |  |

| Rafiganj rail bridge | Rafiganj | India | 10 September 2002 | Possible terrorist sabotage resulting in a train derailment | 130+ killed, 150+ injured | Fifteen train cars derailed when a bridge over the Dhave River collapsed, with two cars and an unknown number of people falling into the river. 130 bodies were recovered, but the full death toll is unknown. | ||

| Chubut River Bridge disaster | Chubut River, Chubut Province | Argentina | 19 September 2002 | Pedestrian suspension bridge | Excess weight due to passers-by | 9 killed, + 5 injured | Total collapse | Collapse of the pedestrian suspension bridge when more than 50 students and teachers of a school who were running in the area crossed it when the capacity of the bridge support was maximum of three people. |

| Marcy Pedestrian Bridge Collapse | Marcy, New York | United States | 11 October 2002 | Pedestrian bridge under construction | Bridge twisted and collapsed over State Route 49 while under construction. The expressway and the bridge itself were closed to the public at the time. | 1 killed, 9 injured[57] | Total collapse | Bridge collapsed as workers were screeding a concrete surface on the bridge. The machine had made it to the bridge's midspan before the entire bridge twisted and collapsed. Workers who had been working on the bridge had described it being notably "bouncy" leading up to the collapse.[58] |

| Sgt. Aubrey Cosens VC Memorial Bridge | Latchford, Ontario, | Canada | 14 January 2003 | Partial failure under load of transport truck during severely cold temperatures. Fatigue fractures of three steel hanger rods cited to be primary reason for failure. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Partial failure of bridge deck. Overhead superstructure undamaged. | Bridge reopened after complete reconstruction. Existing overhead arch remained, however new bridge deck was designed to be supported by sets of 4 hanger cables, where the existing deck was designed for single hanger cables. | |

| Kinzua Bridge | Kinzua Bridge State Park, Pennsylvania | United States | 21 July 2003 | Historic steel rail viaduct | Hit by tornado | 0 killed | Partial collapse |  |

| Interstate 95 Howard Avenue Overpass | Bridgeport, Connecticut | United States | 26 March 2004 | Girder and floorbeam | Car struck a truck carrying 8,000 US gallons (30,000 litres; 6,700 imperial gallons) of heating oil, igniting a fire that melted the bridge superstructure, causing collapse of the southbound lanes | 0 killed, 1 injured | Partial collapse | Northbound lanes shored up with falsework and reopened 3 days later; temporary bridge installed to carry southbound lanes. New permanent bridge completed in November 2004. |

| Big Nickel Road Bridge | Sudbury, Ontario | Canada | 7 May 2004 | 0 killed | Collapsed onto roadway below during construction | [59][60] | ||

| C-470 overpass over I-70 | Golden, Colorado | United States | 15 May 2004 | As part of a construction project, a girder twisted, sagged, and fell onto I-70. An SUV was driving eastbound and struck the fallen girder; the top of the vehicle was torn off and the three passengers died instantly.[61] | 3 killed, 0 injured | Girder collapse | ||

| Mungo Bridge[62] | Cameroon | 1 July 2004 | Steel girder for road traffic | Partial collapse | Yet to be repaired[when?] | |||

| Loncomilla Bridge | near San Javier | Chile | 18 November 2004 | Concrete bridge for vehicle traffic over Maule River | The structure was not built on rock, but rather on fluvial ground. | 0 killed, 8 injured | Partial collapse | Bridge was later repaired |

| I-10 Twin Span Bridge | New Orleans and Slidell, Louisiana | United States | 29 August 2005 | Two parallel trestle bridges crossing the eastern end of Lake Pontchartrain | After Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005, the old Twin Spans suffered extensive damage, as the rising storm surge had pulled or shifted bridge segments off their piers. | 0 killed, 0 injured | The eastbound span was missing 38 segments with another 170 misaligned, while the westbound span was missing 26 segments with 265 misaligned. | Bridge was reconstructed but later replaced with two new spans due to vulnerability to storm surges. |

| Biloxi Bay Bridge | Biloxi, Mississippi | United States | 29 August 2005 | Two parallel trestle bridges crossing the eastern end of the Biloxi Bay | After Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005, the original U.S. Route 90 crossing over the Biloxi Bay suffered extensive damage, as the rising storm surge shifted bridge segments off their piers. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Bridge was replaced in 2007 with a new design aimed to withstand hurricane-force winds and flooding. | |

| Veligonda Railway Bridge | India | 29 October 2005 | Railway bridge | flood washed rail bridge away | 114 killed | |||

| Almuñécar motorway bridge | Almuñécar, province of Granada | Spain | 7 November 2005 | Motorway bridge | Part collapsed during construction, reason unknown | 6 killed, 3 injured | Partial collapse during construction; all the victims were workers. | A 60-metre (200 ft) long part fell 50 metres (160 ft) |

| Caracas-La Guaira highway, Viaduct #1 | Tacagua | Venezuela | 19 March 2006 | Highway viaduct over a gorge | Landslides | 0 killed, 0 injured | Total collapse | Demolished, it was rebuilt and reopened on 21 June 2007 |

| E45 Bridge | Nørresundby | Denmark | 25 April 2006 | Road bridge | Collapsed during reconstruction due to miscalculation | 1 killed | Bridge total damage | The road under the bridge were partially reopened 3 days later. The bridge was reconstructed (again) and opened 18 months later[63] |

| Interstate 88 Bridge | Unadilla, New York | United States | 28 June 2006 | Road bridge | Collapsed during Mid-Atlantic United States flood of 2006 | 2 killed[65] | Bridge total damage | NYSDOT started construction to replace the section of highway almost immediately, and it was re-opened 31 August 2006.[66] |

| Yekaterinburg bridge collapse | Yekaterinburg | Russia | 6 September 2006 | Collapse during construction | 0 killed, 0 injured | |||

| Highway 19 overpass at Laval (De la Concorde Overpass collapse) | Laval, Quebec | Canada | 30 September 2006 | Highway overpass | Shear failure due to incorrectly placed rebar, low-quality concrete | 5 killed, 6 injured | 20-metre (66 ft) section gave way | Demolished; was rebuilt, reopened on 13 June 2007.[67] |

| Nimule | Nimule | Kenya/Sudan | October 2006 | Struck by truck overloaded with cement | ||||

| Pedestrian bridge | Bhagalpur | India | December 2006 | 150-year-old pedestrian bridge (being dismantled) collapsed onto a railway train as it was passing underneath.[68] | More than 30 killed | |||

| Run Pathani Bridge Collapse | 80 km (50 miles) east of Karachi, | Pakistan | 2006 | Collapsed during the 2006 monsoons | ||||

| Railway bridge | Eziama, near Aba | Nigeria | December 2006 | Unknown | Unknown killed | Restored 2009[69] | ||

| Southeastern Guinea | Guinea | March 2007 | Bridge collapsed under the weight of a truck packed with passengers and merchandise.[70] | 65 killed | ||||

| South Korea | 5 April 2007 | Parts of a bridge collapses during construction | 5 killed, 7 injured | Bridge being built between the two Southern Islands.[71] | ||||

| MacArthur Maze | Oakland, California | United States | 29 April 2007 | Tanker truck crash and explosion, resulting fire softened steel sections of flyover causing them to collapse. | 1 injured in crash, 0 from collapse | Span rebuilt in 26 days. | ||

| Highway 325 Bridge over the Xijiang River | Foshan, Guangdong | People's Republic of China | 15 June 2007 | Motorway bridge | Struck by vessel | 8 killed, unknown injured | Section collapsed | Unknown |

| Gosford Culvert washaway | Gosford, New South Wales | Australia | 8 June 2007 | Culvert collapse[72] | 5 killed (all drowned) | |||

| Minneapolis I-35W bridge over the Mississippi River | Minneapolis, Minnesota | United States | 1 August 2007 | Arch/truss bridge | The NTSB said that undersized gusset plates, increased concrete surfacing load, and weight of construction supplies/equipment caused this collapse. | 13 killed, 145 injured | Total bridge failure |  |

| Tuo River bridge | Fenghuang, Hunan | People's Republic of China | 13 August 2007 | Unknown | It is believed to be linked to the fact that local contractors often opt for shoddy materials to cut costs and use migrant laborers with little or no safety training. Exact cause remains unknown. | 34 killed, 22 injured | Total collapse | Collapsed during construction as workers were removing scaffolding from its facade |

| Harp Road bridge | Oakville, Washington | United States | 15 August 2007 | Main thoroughfare into Oakville over Garrard Creek, Grays Harbor County | Collapsed under weight of a truck hauling an excavator[73][74] | 0 killed, 0 injured | Majority to total collapse; temporary or permanent bridge is needed. | Approximate weight of load was 180,000 pounds (82,000 kg); bridge is rated at 35,000 pounds (16,000 kg). Residents must take a 23-mile (37 km) detour. |

| Water bridge | Taiyuan, Shanxi province | People's Republic of China | 16 August 2007 | 180t vehicle overloaded bridge designed for 20t[75] | unknown | Total collapse of 1 span of 2 | ||

| Shershah Bridge – Section of the Northern Bypass, Karachi | Karachi | Pakistan | 1 September 2007 | Overpass bridge | Investigation underway | 5 killed, 2 injured | Collapse may have been caused because of lack of material strength. The reconstruction is in progress.[when?] | |

| Flyover bridge | Punjagutta, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh | India | 9 September 2007 | During construction | 15–30 killed | [76] | ||

| Cần Thơ Bridge | Cần Thơ | Vietnam | 26 September 2007 | Collapse of a temporary pillar due to the sandy foundation it was set on.[77] | 55 killed, hundreds injured | Section buckled while construction was underway |  | |

| Chhinchu suspension bridge | Nepalgunj, Birendranagar | Nepal | 25 December 2007 | Overcrowded suspension bridge collapsed | 19 killed, 15 missing | |||

| Jintang Bridge | Ningbo, Zhejiang province | People's Republic of China | 27 March 2008 | Ship hit lower support structure of bridge[75] | 4 killed, 0 Injured | 60m span of under-construction bridge collapsed | ||

| The Cedar Rapids and Iowa City Railway (CRANDIC) bridge | Cedar Rapids, Iowa | United States | 12 June 2008 | Railroad bridge | During June 2008 Midwest floods | 0 killed, 0 injured | Three of the bridge's four steel spans were swept into the river along with 15 CRANDIC rail cars loaded with rock | The Cedar River was still swollen in this image taken 10 days after the bridge's collapse. |

| Road bridge | Studénka | Czech Republic | 8 August 2008 | Train crashed into a road bridge over the railway under construction, which collapsed on the track immediately before the arrival of a train | 8 killed, 70 injured |  | ||

| Somerton Bridge | Somerton, New South Wales | Australia | 8 December 2008 | Timber road bridge | Heavy flooding | None | Collapse of northern span | Bridge collapsed during heavy flooding due to poor maintenance[78] |

| Devonshire Street pedestrian bridge | Maitland, New South Wales | Australia | 5 March 2009 | Footbridge | Oversized truck clipping main span | 0 killed, 4 injured (Car & Truck Drivers) | Main span falling on New England Highway, road closed for 4 days | Replaced by taller Footbridge 18 months later[79] |

| Popp's Ferry Bridge | Biloxi, Mississippi | United States | 20 March 2009 | Bascule bridge crossing Back Bay Biloxi | A tugboat pushing eight barges hit the bridge pilings | 0 killed, 0 injured | Two ninety-foot sections of the bridge dropped into the water[80] | The bridge reopened to traffic on April 25, 2009[81] |

| Bridge on SS9 over River Po | Piacenza | Italy | 30 April 2009 | Road bridge | Collapsed due to flood of River Po | 0 killed, 1 injured | Replaced by a temporary floating bridge 6 months later, then by a definitive new bridge that opened on 18 December 2010[82] | |

| Overpass on Hongqi Road | Zhuzhou, Hunan | People's Republic of China | 17 May 2009 | Road bridge | Collapsed during demolishing process[83] | 9 killed, 16 injured, 24 vehicles damaged | ||

| 9 Mile Road Bridge at I-75 | Hazel Park, Michigan | United States | 15 July 2009 | Road bridge | Collapsed due to tanker accident[84] | 0 killed, 1 injured | Rebuilt and reopened on 11 December of that year | |

| Broadmeadow Viaduct | Broadmeadow – 13 km (8.1 miles) north of Dublin | Ireland | 21 August 2009 | Railway bridge | 0 killed, 0 injured | One span of viaduct collapsed after tidal scouring of foundations;— first reported by local Sea-scouts. | [85] | |

| Tarcoles Bridge | Orotina | Costa Rica | 22 October 2009 | Suspension bridge built 1924, 270-foot (82 m) span. | Overload by heavy trucks and dead loads (water pipes).[86] | 5 killed, 30 injured | Bridge total damage | |

| San Francisco – Oakland Bay Bridge | Connects San Francisco and Oakland, California | United States | 27 October 2009 | I-80 | Two tension rods and a crossbeam from a recently installed repair collapsed during the evening commute, causing the bridge to be closed temporarily. | 0 killed, 1 injured | During an extended closure as part of the eastern span replacement of the San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge over the 2009 Labor Day holiday, a critical failure was discovered in an eyebar that would have been significant enough to cause a closure of the bridge.[87] Emergency repairs took 70 hours and were completed on 9 September 2009. This is the repair that failed. | |

| Railway Bridge RDG1 48 over the River Crane near Feltham | Feltham | England | 14 November 2009 | Brick arch railway bridge built 1848 | Undermined by scour from river.[88] | No injuries . | River span beyond repair. | Rebuilt as reinforced concrete. |

| Northside Bridge, Workington. Navvies Footbridge, Workington. Camerton Footbridge, Camerton. Memorial Gardens footbridge, Cockermouth. Low Lorton Bridge, Little Braithwaite Bridge. | Cumbria | England | 21 November 2009 | Traditional sandstone bridges. | Very intense rainfall produced extreme river loads that overwhelmed all the bridges.[89] | 1 police officer killed | All bridges destroyed or damaged beyond repair | See Barker Crossing. |

| Kota Chambal Bridge | Kota, Rajasthan | India | 25 December 2009 | Under-Construction Bridge | Inexperience Official[90] | 48 killed, several injured[91] | Total Collapse | |

| Myllysilta | Turku | Finland | 6 March 2010 | Bridge bent 143 centimetres (56 in) due to structural failures of both piers | 0 killed, 0 injured | Demolished June–July 2010 | ||

| Gungahlin Drive Extension bridge | Canberra, Australian Capital Territory | Australia | 14 August 2010 | Concrete road bridge | Unknown | 15 workers injured | Collapse of the half-built span |  |

| Guaiba's Bridge (BR-290) | Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul | Brazil | 1 October 2010 | Concrete and steel bridge[94] | Braking system (electrical) failure stuck the main span 9 meters above the lane rendering the bridge useless by (at least) 3 hours.[95] | 0 killed, 0 injured | Bridge fixed | Damaged probably due to a vessel which collided, bending the main span on April 30, 2008.[96] |

| Laajasalo pedestrian bridge | Helsinki | Finland | 22 November 2010 | Steel reinforced concrete | Bridge collapsed on a van and a taxi in when a personnel lift truck with the lift by mistake elevated passed under the bridge.[97][98] | 1 killed, 2 injured | Collapsed on the road beneath | Both other cars were driving in the opposite direction. The van driver died and taxi driver and passenger were injured. Bridge now rebuilt. |

| Overbridge over Chengdu-Kunming Freeway | Zigong | People's Republic of China | 1 July 2011 | Truck crashed against concrete support pillar[75] | Overbridge destroyed, fell onto highway. | |||

| Gongguan Bridge | Wuyishan, Fujian | People's Republic of China | 14 July 2011 | Overloading | 1 killed, 22 Injured | Total collapse | Entire bridge collapsed, tourist bus with 23 people on board crashed to ground | |

| No. 3 Qiantang River Bridge over Qiantang River | Hangzhou, Zhejiang province | People's Republic of China | 15 July 2011 | Overloading | 0 killed, 1 Injured | Partial collapse leaving a 20-meter-long, 1-meter-wide pit in one lane | Collapse due to two trucks each loaded with over 100 tonnes of goods crossing bridge[75] | |

| Baihe Bridge in Huairou district | Beijing | People's Republic of China | 19 July 2011 | Bridge designed for max. 46 tonne vehicles, truck overloaded with 160 tons of sand caused it to collapse. | 0 killed, 0 Injured | Entire 230m bridge destroyed. | ||

| Kutai Kartanegara Bridge | Tenggarong, East Kalimantan | Indonesia | 26 November 2011 | Suspension bridge | Human error. As workers were repairing a cable during maintenance work, a support cable snapped, causing the roadway to fall into the 50-metre-deep Mahakam River. Although poor maintenance, fatigue in the construction material of cable hanger, and the quality of material may have been the cause of the collapse, the exact cause remains unknown and undetermined. | 20 killed, 40 injured (33 missing) | Deck completely destroyed, 2 bridge pillars were standing at the time of the collapse. |  |

| Eggner's Ferry Bridge (1932) over Kentucky Lake (Tennessee River) | Between Trigg County, Kentucky and Marshall County, Kentucky | United States | 27 January 2012 | Truss bridge | The MV Delta Mariner struck the bottom portion of a span of the bridge when travelling in the incorrect channel of the river. | 0 killed, 0 Injured | Span over the recreational channel of the river collapsed. | Emergency repairs to bridge completed on May 25, 2012. There were preexisting plans before the collapse to replace the bridge with a 4-lane bridge over the river. The new bridge opened in April 2016, and the original bridge was demolished that July. |

| Limfjord Railway Bridge | Aalborg | Denmark | 28 March 2012 | steel beam, openable | Ship collision | none | Mechanical damage | All rail traffic cancelled for over a year, no alternative route. Reopened April 29, 2013. |

| Jay Cooke State Park Swinging Bridge | Carlton, Minnesota | United States | 20 June 2012 | Pedestrian swinging wooden plank and cable | Raging floodwaters | 0 killed, 0 injured | Multiple wooden planks washed away. Cables stayed intact. | Closed for repairs. Reopened November 1, 2013. |

| Beaver River Trestle Bridge | Alberta | Canada | 22 June 2012 | wood, concrete, metal trestle. | Three men set the bridge on fire.[99] | none | Bridge badly damaged and closed. | Bridge did not carry rail traffic anymore, and carried pedestrians, part of the Iron Horse Trail. Another small fire was set in 2015. Bridge is being rebuilt.[100] |

| Guangchang Hedong Bridge | Guangchang County, Fuzhou City, Jiangxi Province | People's Republic of China | 8 August 2012 | steel, concrete | 2 killed, 2 injured | |||

| Yangmingtan Bridge over the Songhua River | Harbin | People's Republic of China | 24 August 2012 | Suspension bridge | Overloading; usage of unsuitable building material (suspected)[101] | 3 killed, 5 injured | 100-metre section of a ramp of the eight-lane bridge dropped 100 feet to the ground. | Main bridge reopened on the same day, ramp still defunct. |

| Tallon Bridge over the Burnett River | Bundaberg, Queensland | Australia | 29 January 2013 | Concrete road bridge | Flood damage[102] | No injuries reported | Partial collapse of the bridge | |

| Bridge under construction for road E6 at Lade/Leangen | Trondheim | Norway | 8 May 2013 | Bridge collapsed under construction[103] | 2 killed | |||

| I-5 Skagit River Bridge collapse | Mount Vernon, Washington | United States | 23 May 2013 | Polygonal Warren through truss bridge | Oversized semi-truck load carrying drilling equipment from Alberta clipped top steel girder causing bridge collapse. | 0 killed, 3 injured | One 167 foot span collapsed. | Truss bridges like this one require both the top and the bottom to remain equal in strength and solidity. When the truck hit the top girder, or girders, this caused the pressure/squeeze system to fail, which made the bridge fold up. The design was outdated; more modern types of truss can better withstand such forces. |

| Pedestrian bridge over Moanalua Freeway | Honolulu, Hawaii | United States | 6 October 2012 | Concrete Pedestrian Bridge | A dump truck was towing a trailer carrying a forklift, which impacted the pedestrian bridge over Moanalua Road. | No serious injuries were reported and no ambulances were sent to the scene[104] | ||

| Scott City roadway bridge collapse | Scott City, Missouri | United States | 25 May 2013 | Concrete road bridge | A Union Pacific train T-boned a Burlington Northern Santa Fe train outside of Scott City, Missouri, at approximately 2:30 am. The impact caused numerous rail cars to hit a support pillar of a highway overpass, collapsing two sections of the bridge onto the rail line. Two cars ended up driving onto the collapsed sections, injuring three people in one vehicle and two in the other. Two people on one of the trains were also injured.[105][106] | 7 injured | Two roadway bridge sections collapsed onto the rail line below. | |

| Wanup train bridge | Sudbury, Ontario | Canada | 2 June 2013 | Steel bridge | Train trestle over the Wanapitei River near Sudbury, Ontario was struck by derailed railcar | 0 killed, 0 injured | Total bridge collapse | CP trains temporarily diverted over CN track. Bridge reconstructed with new pier in 9 days. |

| CPR Bonnybrook Bridge | Calgary, Alberta | Canada | 27 June 2013 | Steel railroad bridge | Partial pier collapse due to scouring from flood event of the Bow River | 0 killed, 0 injured | Partial bridge collapse | [107] |

| Acaraguá bridge collapse | Oberá, Misiones | Argentina | 12 April 2014 | Concrete road bridge | The total collapse of a road bridge over the Acaraguá river, when a passenger bus circulated, caused three dead and thirty wounded. | 3 killed, 30 injured | Total bridge collapse | |

| Cable Bridge Surat | Surat, Gujarat | India | 10 June 2014 | 3-Way Interchange Flyover Bridge, A part of River Bridge; Concrete and steel bridge | Collapsed during construction, Design flaw in curvature section of a span resulted in collapse of a curved span slab during the removal of staging plates. | 10 killed, 6 injured | Total collapse of one wing. | Bridge constructed after necessary modification in design.[108] |

| Belo Horizonte overpass collapse | Belo Horizonte | Brazil | 3 July 2014 | Steel and concrete bridge Part of improvements for the 2014 FIFA World Cup |

Construction error | 2 killed, 22 injured | Total bridge collapse | Bridge collapsed while under construction |

| Motorway bridge collapse during construction | Near Copenhagen | Denmark | 27 September 2014 | Steel and concrete bridge | Construction error | Workers received mild injuries | Partial bridge collapse | Bridge collapsed during concrete casting, with debris falling onto open motorway below and narrowly missing vehicles, closing major motorway E47 for several days. The remains of the bridge were subsequently demolished and a replacement built elsewhere.[109] |

| Hopple Street Overpass over I-75 Southbound | Cincinnati, Ohio | United States | 19 January 2015 | Road bridge | Old Northbound Hopple Street offramp totally collapsed onto roadway below during demolition[110] | 1 killed, 0 injured | Total bridge collapse | Bridge collapsed prematurely due to a faulty demolition process |

| Plaka Bridge | Plaka-Raftaneon, Epirus | Greece | 1 February 2015 | Stone bridge | Flash flood ripped foundations from the riverbanks | 0 killed, 0 injured | Central section of the bridge collapsed | |

| Skjeggestad Bridge | Holmestrand, Vestfold | Norway | 2 February 2015 | Box girder bridge, Motorway | Partial pier displacement due to a landslide. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Partial bridge collapse of Southbound span |  |

| Himera Viaduct | Scillato, Sicily | Italy | 10 April 2015 | Continuous span girder bridge, Motorway | Partial pier displacement due to a landslide. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Partial bridge collapse of Southbound span | |

| Pennsy Bridge | Ridgway, Pennsylvania | United States | 18 June 2015 | Cast-in-place concrete rigid frame | Partial collapse during demolition. | 0 killed, 3 injured | Partial bridge collapse of north half of span | Structure was longitudinally saw cut, south half of the structure was open to traffic while the north half was in the process of being demolished. North half collapsed with 51-ton excavator on the bridge. Underlying reason to be determined. Northbound span shut down precautionary. After collapse, structure was fully closed and south half was demolished. New structure was built and opened to traffic on 26 October 2015.[111] |

| I-10 Bridge | Southern California | United States | 20 July 2015 | Abutment displacement due to stream meander, which caused abutment scour. It caused by the remnants of Hurricane Dolores record breaking rainfall. | 0 killed, 1 injured | Partial bridge collapse of span | ||

| Bob White Covered Bridge | Patrick County, Virginia | United States | 29 September 2015 | Covered timber bridge | Destruction due to major flooding | 0 killed, 0 injured | Bridge collapsed and washed away during flooding caused by severe rainstorm. | |

| Grayston Pedestrian and Cycle Bridge | M1 road (Johannesburg) | South Africa | 14 October 2015 | Single pylon cable stayed concrete bridge | Collapse of temporary works during construction | 2 killed, 19 injured | Contractor deviated from General Arrangement Drawing provided by equipment supplier. | |

| Friesenbrücke | Germany | 3 December 2015 | bascule bridge | damaged by the cargo ship Emsmoon | 0 killed, 0 injured | Central part, the moving section, was destroyed. |  | |

| Tadcaster Bridge | North Yorkshire | England | 29 December 2015 | 300 year old Stone Bridge Grade II Listed on 12 July 1985 | Partial collapse due to flood damage, also causing substantial gas leak | No injuries as bridge had been closed for two days as a precautionary measure | North East side of bridge collapsed severing connections between the two sides of the town |  |

| Nipigon River Bridge | Ontario | Canada | 10 January 2016 | Cable-stayed bridge carrying the Trans-Canada Highway | Bolts holding uplift bearing to main girders of the bridge snapped,[112] due to design and construction errors.[113] | No injuries were reported | West side of bridge separated from abutment and rose 60 cm above grade, but not seriously damaging the span | Newly constructed bridge failed after only 42 days of use. Because the bridge failure severed the only road link within Canada between Eastern and Western Canada,[114] a temporary repair was completed the next day by adding weights to depress the span into position.[115] |

| Perkolo Bridge (sv) | Nord-Fron Municipality (near Sjoa in Sel Municipality) | Norway | 17 February 2016 | Truss bridge with glued laminated timber | Mathematical error[116] | 0 dead, 1 injured[117] | Complete collapse | |

| Vivekananda Flyover Bridge | Kolkata | India | 31 March 2016 | Steel girder flyover bridge | Bolts holding together a section of the bridge snapped.[118] Reason for bolt failure remains unknown. | 27 killed, 80+ injured | Fly over on Vivekananda Road Kolkata | Collapse of bridge under construction |

| May Ave. Overpass | Oklahoma City, Oklahoma | United States | 19 May 2016 | Girder bridge over expressway | An over-sized load hit the bridge, causing a section of the deck to fail | No injuries were reported. | Partial collapse | Driver was found responsible for collapse. |

| Savitri River Bridge | Maharashtra | India | 2 August 2016 | Stone arched bridge over a river | Dilapidated condition. About 100 years old. | Two buses and few cars plunged into the flooded river. 28 dead. | Partial collapse | The bridge collapsed in the middle of the night, sending many vehicles plunging into the river. A nearby garage worker heard the noise and went to the bridge to stop cars, preventing further casualties. |

| Railway bridge | Tolten River | Chile | 19 August 2016 | Suspension bridge with steel deck truss. | Cause undetermined—happened as a freight train was crossing the bridge | 0 killed, 0 injured | Partial collapse | 3 spans collapsed into river on 118-year-old bridge[119][120] |

| Nzi River Bridge | near Dimbokro | Ivory Coast | 6 September 2016 | Steel railway bridge | While train crossing | 0 injured | One span of 1910 bridge collapsed.[121] | |

| Yellow 'Love' Bridge | Klungkung Regency | Indonesia | 16 October 2016 | Wooden suspension bridge | Snapped sling due to overloading | 9 killed, 30 injured | Whole bridge plunged onto river below | Slings snapped while 70 people were on the bridge during Nyepi celebration in Bali. Authorities stated that the sling cables that snapped could have been caused by overloading. Most witnesses stated that before the collapse, the bridge had swayed and shook for several times.[122][123] |

| Lecco overpass | Province of Lecco | Italy | 28 October 2016 | Concrete girder overpass. | Cause undetermined—happened as 108-tonne truck was crossing the bridge | 1 killed, 5 injured | Centre span collapsed onto roadway below[124] | Allegations have been made that the maintenance company, ANAS, had requested that the bridge be closed before the collapse and that the request was denied by Lecco, pending documentation.[125] |

| Camerano overpass | Province of Ancona | Italy | 9 March 2017 | 2 killed, 3 injured | Centre span collapsed onto roadway below | |||

| Pfeiffer Canyon Bridge | Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park Big Sur, California |

United States | 11 March 2017 | Concrete bridge | Massive rain and landslide | 0 killed | The foundation for one of the two piers was undermined by the landslide causing the pier to slide downhill with the earth around it and fail, and the deck to sag. | Bridge collapse resulted in a 6-hour detour to get from one side of Big Sur to the other side, effectively splitting the community in half. It was replaced with a 310-foot-long span steel bridge that opened to traffic on 13 October 2017.[126] |

| I-85N, Atlanta | Atlanta, Georgia | United States | 30 March 2017 | Concrete Overpass | Fire (allegedly arson) involving HDPE pipe and other construction materials stored under bridge critically weakened structure, which collapsed. | 0 killed, 0 injured | Investigation pending as to fire cause |  |

| Sanvordem River Bridge | Curchorem, Goa | India | 18 May 2017 | Portuguese era footbridge made of steel | Dilapidation, bridge was closed for use. | 2 killed, 30 missing | Bridge is scheduled for demolition. | The bridge was closed for use, but several people wanted to watch the rescue work of an alleged suicidal. |

| Sigiri Bridge | Nzoia River, Budalangi, Busia County | Kenya | 26 June 2017 | Three span bridge with composite steel beam and concrete deck. | Collapsed during construction | 0 killed, 3 injured | Unknown | Opinion is casting of decks was incorrectly sequenced. |

| Bridge No 'B1187 – 1978' on N3 at intersection with M2 | Johannesburg | South Africa | 9 August 2017 | Multi-span reinforced concrete foot bridge. | Collapsed at about 1:14 am on a public holiday | 0 killed, 5 injured, 1 with critical injuries | Unknown. No fatalities confirmed. | Median column destructed by impact caused by 18.1 ton roll of coiled steel[127] |

| Ramat Elhanan Pedestrian Crossing on Highway 4 | Highway 4, between Bnei Brak and Giv'at Shmuel | Israel | 14 August 2017 | concrete pedestrian bridge | about 19:48 | 1 killed | Vehicle collision.[128] | |

| Provincial road Ksanthi-Iasmos at Kompsatos river crossing | Eastern Macedonia and Thrace district | Greece | 10 September 2017 | 3x simple supported spans of precast prestressed concrete girders, supported on reinforced concrete piers on shallow foundations in river bed. | Probable cause is the time evolving scour and poor inspection. Exact cause remains unknown. | 0 injured | One span collapsed and the supporting pier was inclined from the vertical orientation. | Many pictures from the collapse (Greek text) can be found here[129] and a newspaper short report (English text) here[130] |

| Troja footbridge | Prague | Czech Republic | 2 December 2017 | simple suspension concrete pedestrian bridge | Probably corrosion or damage of the suspension cables, impossibility of their effective inspection, impact of 2002 flood supposed. | 4 injured (2 heavily) | Total collapse. |  |