Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Private good

View on Wikipedia

A private good is defined in economics as "an item that yields positive benefits to people"[1] that is excludable, i.e. its owners can exercise private property rights, preventing those who have not paid for it from using the good or consuming its benefits;[2] and rivalrous, i.e. consumption by one necessarily prevents that of another. A private good, as an economic resource is scarce, which can cause competition for it.[3] The market demand curve for a private good is a horizontal summation of individual demand curves.[4]

Unlike public goods, such as clean air or national defense, private goods are less likely to have the free rider problem, in which a person benefits from a public good without contributing towards it. Assuming a private good is valued positively by everyone, the efficiency of obtaining the good is obstructed by its rivalry; that is simultaneous consumption of a rivalrous good is theoretically impossible. The feasibility of obtaining the good is made difficult by its excludability, which means that people have to pay for it to enjoy its benefits.[5]

One of the most common ways of looking at goods in the economy is by examining the level of competition in obtaining a given good, and the possibility of excluding its consumption; one cannot, for example, prevent another from enjoying a beautiful view in a public park, or clean air.[6]

Definition matrix

[edit]Example of a private good

[edit]An example of the private good is bread: bread eaten by a given person cannot be consumed by another (rivalry), and it is easy for a baker to refuse to trade a loaf (exclusive).

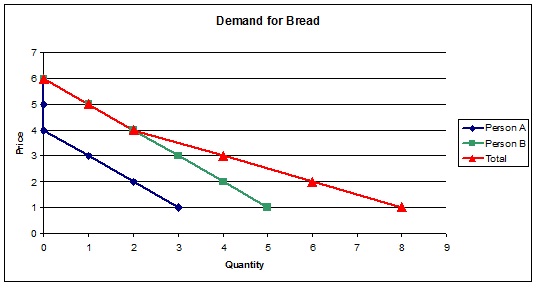

To illustrate the horizontal summation characteristic, assume there are only two people in this economy and that:

- Person A will purchase: 0 loaves of bread at $4, 1 loaf of bread at $3, 2 loaves of bread at $2, and 3 loaves of bread at $1

- Person B will purchase: 0 loaves of bread at $6, 1 loaf of bread at $5, 2 loaves of bread at $4, 3 loaves of bread at $3, 4 loaves of bread at $2, and 5 loaves of bread at $1

As a result, a new market demand curve can be derived with the following results:

| Price per loaf of bread | Loaves of bread | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Person A | Person B | Total | |

| $6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| $5 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| $4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| $3 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| $2 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| $1 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

References

[edit]- ^ Nicholson, Walter (2004). Intermediate Microeconomics And Its Application. United States of America: South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning. p. 59. ISBN 0-324-27419-X.

- ^ Ray Powell (June 2008). "10: Private goods, public goods and externalities". AQA AS Economics (paperback). Philip Allan. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-340-94750-0.

- ^ Hallgren, M.M.; McAdams, A.K. (1995). "A model for efficient aggregation of resources for economic public goods on the internet". The Journal of Electronic Publishing. 1. doi:10.3998/3336451.0001.125. hdl:2027/spo.3336451.0001.125.

- ^ "Public Goods: Demand". AmosWEB Encyclonomic WEB*pedia. AmosWEB LLC. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Malkin, J.; Wildavasky, A. (1991). "Why the traditional distinction between public and private goods should be abandoned". Journal of Theoretical Politics. 3 (4): 355–378. doi:10.1177/0951692891003004001. S2CID 154607937.

- ^ "Rivalry and Excludability in Goods". Living Economics. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

Private good

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Definition

In economics, a private good is defined as a resource or product that exhibits both rivalry and excludability in consumption. Rivalry implies that one individual's use of the good reduces or eliminates the availability for others, while excludability means mechanisms exist to restrict access to paying consumers only.[4] The term originated in Paul Samuelson's seminal 1954 paper, "The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure," which contrasted private goods with public goods to analyze efficient government spending and resource allocation. In this framework, Samuelson highlighted how private goods differ from collective consumption items by their individualized, competitive nature. Private goods align with market-based allocation because their rivalry and excludability enable pricing mechanisms and property rights to efficiently distribute them to highest-value users, compensating producers and preventing free-riding.[1][5]Rivalry and Excludability

Rivalry in private goods refers to the characteristic that the consumption of the good by one individual diminishes or eliminates its availability for consumption by others, thereby reducing the marginal utility derived from additional users. This property ensures that resources are allocated on a competitive basis, where one person's use directly competes with another's. For instance, if a single unit of a private good, such as an apple, is consumed by one person, zero units remain for others, illustrating the zero-sum nature of consumption. Mathematically, rivalry is represented by the constraint that the sum of individual consumptions equals the total supply: where denotes the quantity consumed by individual , is the number of consumers, and is the fixed total quantity available; this contrasts with non-rival goods where simultaneous consumption does not deplete the resource.[4] Excludability, the second defining trait of private goods, denotes the feasibility of preventing non-paying individuals from accessing or benefiting from the good through enforceable barriers. This allows producers to capture the full value of their output by restricting consumption to those who compensate them appropriately. Legal mechanisms, such as patents, grant exclusive rights to inventors, prohibiting unauthorized use of innovations like pharmaceuticals. Technological solutions, including paywalls on digital content platforms, block access unless payment is made, while physical barriers like fences secure tangible assets such as land or vehicles. These mechanisms collectively enable market transactions by aligning consumption with payment, preventing free-riding.[4][6] The combination of rivalry and excludability in private goods facilitates efficient resource allocation in competitive markets, where the equilibrium price equals the marginal cost of production, ensuring that goods are produced and consumed up to the point where marginal social benefit matches marginal social cost. This outcome promotes Pareto optimality, a state where no reallocation can improve one individual's welfare without reducing another's, as established by the First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics under assumptions of perfect competition and no externalities. Consequently, private goods markets achieve allocative efficiency without requiring external intervention, unlike non-excludable or non-rival goods.[7][8]Classification in Economic Theory

Goods Classification Framework

In economic theory, goods are classified using a 2x2 matrix based on two fundamental characteristics: rivalry in consumption and excludability. Rivalry assesses whether one individual's use of the good reduces its availability or utility to others (rival if yes, non-rival if no), while excludability evaluates whether non-payers can be prevented from accessing the good (excludable if yes, non-excludable if no). This framework yields four categories: private goods (rival and excludable), club goods (non-rival and excludable), common-pool resources (rival and non-excludable), and public goods (non-rival and non-excludable).[4] Private goods are positioned in the quadrant characterized by both high rivalry and high excludability. In this category, consumption by one party inherently diminishes the quantity available to others, and mechanisms such as property rights or pricing can effectively restrict access to authorized users. Representative examples include tangible items like apples or clothing, where physical scarcity enforces rivalry and legal ownership enables exclusion.[4] This matrix derives from the foundational theory of public goods, pioneered by Paul Samuelson in 1954, who modeled public goods based on non-rivalry in consumption, with Richard Musgrave advancing the theory in 1959 by incorporating non-excludability into a broader typology of social goods. The framework was further developed into the explicit 2x2 matrix by economists such as Richard and Peggy Musgrave in 1973 or Elinor and Vincent Ostrom in 1977, which later crystallized into the standard structure in subsequent analyses. The framework facilitates the diagnosis of market failures by highlighting how private goods align with efficient decentralized allocation through competitive markets, in contrast to other quadrants prone to underprovision or overuse.[4][9]| Characteristic | Rivalrous | Non-Rivalrous |

|---|---|---|

| Excludable | Private goods (e.g., food) | Club goods (e.g., private parks) |

| Non-Excludable | Common-pool resources (e.g., fisheries) | Public goods (e.g., national defense) |