Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Set theory.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Set theory

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Set theory

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Set theory is the branch of mathematics concerned with the study of sets, which are well-determined collections of distinct objects called elements or members, and it forms the foundational framework for virtually all modern mathematical disciplines by defining concepts such as numbers, functions, and relations in terms of sets and the membership relation.[1] Developed primarily by Georg Cantor in the late 19th century, set theory revolutionized mathematics by treating infinite collections as legitimate objects comparable to finite ones, introducing notions like cardinality to measure the "size" of sets and transfinite numbers to extend the natural numbers beyond the finite.[2] Cantor's work, beginning with his 1874 paper on the non-denumerability of the real numbers, established key results such as the uncountability of the continuum and the hierarchy of infinities, laying the groundwork for set theory as an autonomous field.[3]

Early naive set theory, which relied on intuitive notions of sets without formal restrictions, encountered paradoxes like Russell's paradox in 1901, which demonstrated that unrestricted comprehension—allowing any property to define a set—leads to contradictions, such as the set of all sets that do not contain themselves.[1] To resolve these issues, axiomatic set theory emerged in the early 20th century, with Ernst Zermelo's 1908 axiomatization providing the first rigorous system, later refined by Abraham Fraenkel into the Zermelo-Fraenkel (ZF) axioms, which include principles like extensionality (sets are determined by their elements), pairing, union, power set, infinity, and replacement, along with the axiom schema of separation to safely form subsets.[4] The addition of the axiom of choice (AC), which asserts the existence of choice functions for any collection of nonempty sets, completes the standard system known as ZFC, widely accepted as the basis for mathematics due to its consistency with classical theorems and ability to derive all known mathematical structures.[4]

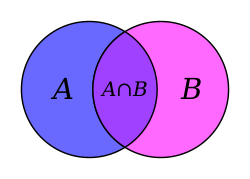

Beyond its foundational role, set theory explores profound questions about the structure of the mathematical universe, including the continuum hypothesis (CH)—Cantor's conjecture that there is no set with cardinality strictly between that of the natural numbers and the real numbers—which was shown by Kurt Gödel in 1940 to be consistent with ZFC and by Paul Cohen in 1963 to be independent of it using forcing techniques.[4] Key operations on sets, such as union, intersection, and complement, enable the construction of complex structures like ordered pairs via the Kuratowski definition , while concepts like ordinals and cardinals provide tools for ordering and sizing infinite sets.[5] Today, set theory not only underpins pure mathematics but also influences computer science through models of computation and database theory, and philosophy via debates on the nature of infinity and mathematical existence.[5]