Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shift Out and Shift In characters

View on Wikipedia

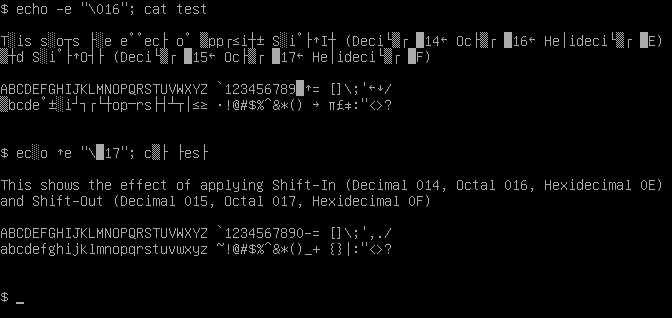

Shift Out (SO) and Shift In (SI) are ASCII control characters 14 and 15, respectively (0x0E and 0x0F).[1] These are sometimes also called "Control-N" and "Control-O".

The original purpose of these characters was to provide a way to shift a coloured ribbon, split longitudinally usually with red and black, up and down to the other colour in an electro-mechanical typewriter or teleprinter, such as the Teletype Model 38, to automate the same function of manual typewriters. Black was the conventional ambient default colour and so was shifted "in" or "out" with the other colour on the ribbon.

Later advancements in technology instigated use of this function for switching to a different font or character set and back. This was used, for instance, in the Russian character set known as KOI7-switched, where SO starts printing Russian letters, and SI starts printing Latin letters again. Similarly, they are used for switching between Katakana and Roman letters in the 7-bit version of the Japanese JIS X 0201.[2][3]

SO/SI control characters also are used to display VT100 pseudographics. Shift In is also used in the 2G variant[4] of SoftBank Mobile's encoding for emoji.

The ISO/IEC 2022 standard (ECMA-35, JIS X 0202) standardises the generalized usage of SO and SI for switching between pre-designated character sets invoked over the 0x20–0x7F byte range. It refers to them respectively as Locking Shift One (LS1) and Locking Shift Zero (LS0) in an 8-bit environment, or as SO and SI in a 7-bit environment.[5] In ISO-2022-compliant code sets where the 0x0E and 0x0F characters are used for the purpose of emphasis (such as an italic or red font) rather than a change of character set, they are referred to respectively as Upper Rail (UR) and Lower Rail (LR), rather than SO and SI.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Linux Programmer's Manual". Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- ^ Japanese Industrial Standards Committee (1975-12-01). The Japanese Katakana graphic set of characters (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-13.

- ^ Japanese Industrial Standards Committee (1975-12-01). The Japanese Roman graphic set of characters (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-14.

- ^ Kawasaki, Yusuke (2010). Emoji encodings and cross-mapping tables in pure Perl.

- ^ ECMA (1994). "7.3: Invocation of character-set code elements". Character Code Structure and Extension Techniques (PDF) (ECMA Standard) (6th ed.). p. 14. ECMA-35.

- ^ Sveriges Standardiseringskommission (1975-12-01). NATS Control set for newspaper text transmission (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-7.

Shift Out and Shift In characters

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Purpose

Shift Out Character

The Shift Out (SO) character is defined as ASCII control character number 14, with a hexadecimal value of 0x0E and decimal value of 14, and is commonly referred to as Control-N.[5][2] Its primary function is to invoke or lock an alternate character set, such as the G1 graphic character set in ISO terminology, thereby enabling the interpretation of subsequent code combinations outside the standard character set until a Shift In character is received.[5][2] Alternatively, in certain device contexts, SO can shift a physical mechanism, such as engaging an alternate color ribbon in printers.[3] Operationally, SO functions as a locking shift mechanism, activating the alternate state persistently for following characters and allowing continuous use of the shifted configuration without repeated invocations, which is countered only by the paired Shift In character to revert to the primary state.[5][2] The standard mnemonic and symbolic representations for SO include the abbreviation "SO" and the caret notation "^N" in various technical documentation and implementations.[5]Shift In Character

The Shift In (SI) character is a control function defined in the ASCII standard as the code point 15, represented in hexadecimal as 0x0F and in decimal as 15, and commonly abbreviated as Control-O or ^O in mnemonic notations.[6] This non-printing character serves to invoke the primary (G0) character set, ensuring that subsequent bit combinations are interpreted according to the default encoding until another control function alters the state. Its primary function is to revert the active character set to the initially designated primary set, such as G0 in the context of code extension techniques, thereby locking any prior shift to an alternate set. In operational terms, SI immediately cancels the effects of a preceding Shift Out (SO) by switching back to the default state, with the change applying to the following characters in the data stream without affecting ongoing control sequences.[6] This mechanism allows for temporary extensions of the character repertoire in 7-bit environments, where SI is specifically employed as a locking-shift function to the G0 set. SI is symbolically represented as SI in standards documentation and ^O in caret notation for control characters, facilitating its identification in programming and terminal contexts.[6] In conjunction with SO, it enables selective invocation of alternate character sets (like G1) for brief sequences before returning to the primary set, supporting efficient handling of multilingual or specialized symbols within constrained code spaces.Historical Development

Origins in Early Teleprinters

The origins of the Shift Out (SO) and Shift In (SI) characters trace back to the mechanical constraints of early 20th-century printing telegraphs, where limited bit widths necessitated mechanisms to toggle between character sets without expanding the code itself. Émile Baudot's pioneering 5-bit code, patented in 1874, laid the foundation by introducing shift functions to access letters, figures, and symbols within a 32-character repertoire, enabling efficient transmission over telegraph lines in devices like synchronous multiplex printers.[7] This approach influenced subsequent systems by allowing dynamic mode switching, a concept directly ancestral to SO and SI for set selection.[7] In the 1900s and 1920s, electro-mechanical teleprinters such as those developed by the Morkrum Company (later Teletype Corporation) incorporated shift mechanisms to control printing operations, including the advancement of colored ribbons—typically red and black—for distinguishing text types in page printers. For instance, Donald Murray's variants of the Baudot code, patented starting in 1901, refined these shifts to optimize keyboard input and tape perforation, facilitating reliable operation in asynchronous start-stop systems used for stock tickers and news services.[7] These innovations addressed the need for dual-mode printing in bandwidth-limited environments, with shifts mechanically locking the typebar or ribbon position until reset.[8] The International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), formalized in the 1920s, standardized these shift operations for global use, employing FIGS (figures/symbols mode) and LTRS (letters mode) to expand the effective character set beyond 5 bits while maintaining compatibility with early teleprinters.[7] ITA2's design, influenced by Murray's enhancements, allowed toggling between upper- and lower-case representations or numerals/punctuation, directly paralleling the later SO and SI functions for set invocation.[8] This was crucial for handling mixed text in mechanical devices, where a single shift code could reconfigure the print head for an entire sequence. Key milestones included the Comité Consultatif International Télégraphique (CCITT)'s adoption of ITA2 in 1930 as the international standard for telegraphy, promoting interoperability across borders.[7] Earlier, in 1922, the U.S. Navy demonstrated radioteletype (RTTY) using Baudot-derived shifts to transmit messages from an airplane to ground stations, highlighting the codes' robustness in wireless applications.[9] By 1924, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) employed similar RTTY systems to send text from shore to ships, further embedding shift mechanisms in maritime and military communications.[9]Inclusion in ASCII Standard

The development of the Shift Out (SO) and Shift In (SI) characters within the ASCII standard began with proposals from the American Standards Association (ASA) X3.4 committee in 1961, as part of efforts to create a unified seven-bit code for information interchange. This initial proposal, influenced by the need to accommodate existing communication practices, assigned SO to position 0/14 and SI to 0/15 for enabling shifts between character sets, drawing directly from teleprinter conventions. The committee's work culminated in the publication of the first ASCII standard, ASA X3.4-1963, on June 17, 1963, which formalized the inclusion of SO and SI in the control character block at decimal positions 14 (0x0E) and 15 (0x0F), respectively.[10][3] The rationale for retaining SO and SI in the seven-bit ASCII design centered on backward compatibility with established teleprinter codes, such as the International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2), despite the standard's goal of assigning fixed positions to characters to eliminate the need for shifting mechanisms. Proponents argued that these control characters were essential for interoperability with legacy equipment used in data communications, allowing efficient switching between uppercase/lowercase or figures/letters without expanding the code beyond seven bits. This decision reflected compromises during committee debates, where non-shifting alternatives—like AT&T's earlier six-unit code proposal—were considered but ultimately rejected in favor of preserving compatibility for practical deployment.[10][11] Key influences on the inclusion came from teleprinter manufacturers, notably Teletype Corporation (a subsidiary of AT&T), whose equipment relied on similar shift functions for ribbon control and character interpretation in five-unit codes. Representatives from Teletype and Western Union participated in the X3.4 deliberations, advocating for SO and SI to ensure the new standard supported existing hardware without requiring widespread replacements. The 1967 revision (USAS X3.4-1967) added definitions for lowercase letters, while the 1968 revision (USAS X3.4-1968), published as ANSI X3.4-1968, maintained these assignments unchanged, solidifying their place in the control block (0x00-0x1F) with minor clarifications to control functions.[10][3][12]Technical Specifications

Code Points and Representation

The Shift Out (SO) character is encoded in the ASCII standard at decimal 14, hexadecimal 0x0E, and binary 0001110 (7-bit representation).[13] The Shift In (SI) character follows immediately at decimal 15, hexadecimal 0x0F, and binary 0001111.[13] These positions place SO and SI within the C0 control character range of ASCII, defined in the original ANSI X3.4-1968 standard and subsequent revisions.[13] In Unicode, SO is mapped to the code point U+000E and SI to U+000F, both within the Basic Latin block (U+0000 to U+007F).[14] These are classified as control characters with no assigned glyph in standard rendering, though they retain their ASCII semantics for compatibility.[14] For visualization in debugging or documentation tools, symbolic representations are sometimes used, such as ␎ (U+240E, SYMBOL FOR SHIFT OUT) for SO and ␏ (U+240F, SYMBOL FOR SHIFT IN) for SI, drawn from the Control Pictures block. The encodings remain consistent in 8-bit extensions of ASCII, where the most significant bit is set to 0 for these 7-bit controls, preserving their positions without alteration.[15] In ISO/IEC 8859 series standards, such as ISO/IEC 8859-1 (Latin-1), SO and SI occupy the same byte values (0x0E and 0x0F) to ensure backward compatibility with 7-bit ASCII.[15] Similarly, in EBCDIC, the encodings align at hexadecimal 0x0E for SO and 0x0F for SI, maintaining equivalence to ASCII control codes despite differences elsewhere in the code page.[16]| Standard | SO Code Point | SI Code Point |

|---|---|---|

| ASCII (7-bit) | Dec: 14, Hex: 0x0E, Bin: 0001110 | Dec: 15, Hex: 0x0F, Bin: 0001111 |

| Unicode | U+000E | U+000F |

| ISO 8859-1 | 0x0E | 0x0F |

| EBCDIC | 0x0E | 0x0F |