Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

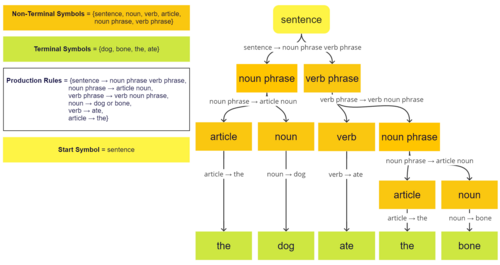

Terminal and nonterminal symbols

View on Wikipedia

In formal languages, terminal and nonterminal symbols are parts of the vocabulary under a formal grammar. Vocabulary is a finite, nonempty set of symbols. Terminal symbols are symbols that cannot be replaced by other symbols of the vocabulary. Nonterminal symbols are symbols that can be replaced by other symbols of the vocabulary by the production rules under the same formal grammar.[2]

A formal grammar defines a formal language over the vocabulary of the grammar.

In the context of formal language, the term vocabulary is more commonly known as alphabet. Nonterminal symbols are also called syntactic variables.

Terminal symbols

[edit]Terminal symbols are those symbols that can appear in the formal language defined by a formal grammar. The process of applying the production rules successively to a start symbol might not terminate, but if it terminates when there is no more production rule can be applied, the output string will consist only of terminal symbols.

For example, consider a grammar defined by two rules. In this grammar, the symbol Б is a terminal symbol and Ψ is both a nonterminal symbol and the start symbol. The production rules for creating strings are as follows:

- The symbol

Ψcan becomeБΨ - The symbol

Ψcan becomeБ

Here Б is a terminal symbol because no rule exists to replace it with other symbols. On the other hand, Ψ has two rules that can change it, thus it is nonterminal. The rules define a formal language that contains countably infinite many finite-length words by the fact that we can apply the first rule any countable times as we wish. Diagram 1 illustrates a string that can be produced with this grammar.

Б Б Б Б was formed by the grammar defined by the given production rules. This grammar can create strings with any number of the symbol БNonterminal symbols

[edit]Nonterminal symbols are those symbols that cannot appear in the formal language defined by a formal grammar. A formal grammar includes a start symbol, which is a designated member of the set of nonterminal symbols. We can derive a set of strings of only terminal symbols by successively applying the production rules. The generated set is a formal language over the set of terminal symbols.

Context-free grammars are those grammars in which the left-hand side of each production rule consists of only a single nonterminal symbol. This restriction is non-trivial; not all languages can be generated by context-free grammars. Those that can are called context-free languages. These are exactly the languages that can be recognized by a non-deterministic push down automaton. Context-free languages are the theoretical basis for the syntax of most programming languages.

Production rules

[edit]A grammar is defined by production rules (or just 'productions') that specify which symbols can replace which other symbols; these rules can be used to generate strings, or to parse them. Each such rule has a head, or left-hand side, which consists of the string that can be replaced, and a body, or right-hand side, which consists of a string that can replace it. Rules are often written in the form head → body; e.g., the rule a → b specifies that a can be replaced by b.

In the classic formalization of generative grammars first proposed by Noam Chomsky in the 1950s,[3][4] a grammar G consists of the following components:

- A finite set N of nonterminal symbols.

- A finite set Σ of terminal symbols that is disjoint from N.

- A finite set P of production rules, each rule of the form

- where denotes the set of all possible finite-length strings over the vocabulary using Kleene star. That is, each production rule replaces one string of symbols that contains at least one nonterminal symbol with another. In the case that the body consists solely of the empty string[note 1], it can be denoted with a special notation (often Λ, e or ε) to avoid confusion.

- A distinguished symbol that is the start symbol.

A grammar is formally defined as the ordered quadruple . Such a formal grammar is often called a rewriting system or a phrase structure grammar in the literature.[5][6]

Example

[edit]Backus–Naur form is a notation for expressing certain grammars. For instance, the following production rules in Backus-Naur form are used to represent an integer (which can be signed):

<digit> ::= '0' | '1' | '2' | '3' | '4' | '5' | '6' | '7' | '8' | '9'

<integer> ::= ['-'] <digit> {<digit>}

In this example, terminal symbols are , and nonterminal symbols are <digit>, <integer>.

[note 2]

Another example is:

In this example, terminal symbols are , and nonterminal symbols are .

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ Rosen, K. H. (2012). Discrete mathematics and its applications. McGraw-Hill. pages 847-851.

- ^ Rosen, K. H. (2018). Discrete mathematics and its applications. McGraw-Hill. page 887.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1956). "Three Models for the Description of Language". IRE Transactions on Information Theory. 2 (3): 113–123. doi:10.1109/TIT.1956.1056813. S2CID 19519474.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1957). Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton.

- ^ Ginsburg, Seymour (1975). Algebraic and automata theoretic properties of formal languages. North-Holland. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-7204-2506-9.

- ^ Harrison, Michael A. (1978). Introduction to Formal Language Theory. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. pp. 13. ISBN 0-201-02955-3.