Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Recursion

View on Wikipedia

Recursion occurs when the definition of a concept or process depends on a simpler or previous version of itself.[1] Recursion is used in a variety of disciplines ranging from linguistics to logic. The most common application of recursion is in mathematics and computer science, where a function being defined is applied within its own definition. While this apparently defines an infinite number of instances (function values), it is often done in such a way that no infinite loop or infinite chain of references can occur.

A process that exhibits recursion is recursive. Video feedback displays recursive images, as does an infinity mirror.

Formal definitions

[edit]

In mathematics and computer science, a class of objects or methods exhibits recursive behavior when it can be defined by two properties:

- A simple base case (or cases) — a terminating scenario that does not use recursion to produce an answer

- A recursive step — a set of rules that reduces all successive cases toward the base case.

For example, the following is a recursive definition of a person's ancestor. One's ancestor is either:

- One's parent (base case), or

- One's parent's ancestor (recursive step).

The Fibonacci sequence is another classic example of recursion:

- Fib(0) = 0 as base case 1,

- Fib(1) = 1 as base case 2,

- For all integers n > 1, Fib(n) = Fib(n − 1) + Fib(n − 2).

Many mathematical axioms are based upon recursive rules. For example, the formal definition of the natural numbers by the Peano axioms can be described as: "Zero is a natural number, and each natural number has a successor, which is also a natural number."[2] By this base case and recursive rule, one can generate the set of all natural numbers.

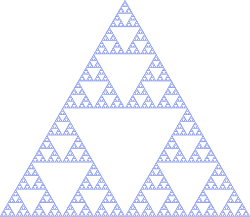

Other recursively defined mathematical objects include factorials, functions (e.g., recurrence relations), sets (e.g., Cantor ternary set), and fractals.

There are various more tongue-in-cheek definitions of recursion; see recursive humor.

Informal definition

[edit]

Recursion is the process a procedure goes through when one of the steps of the procedure involves invoking the procedure itself. A procedure that goes through recursion is said to be 'recursive'.[3]

To understand recursion, one must recognize the distinction between a procedure and the running of a procedure. A procedure is a set of steps based on a set of rules, while the running of a procedure involves actually following the rules and performing the steps.

Recursion is related to, but not the same as, a reference within the specification of a procedure to the execution of some other procedure.

When a procedure is thus defined, this immediately creates the possibility of an endless loop; recursion can only be properly used in a definition if the step in question is skipped in certain cases so that the procedure can complete.

Even if it is properly defined, a recursive procedure is not easy for humans to perform, as it requires distinguishing the new from the old, partially executed invocation of the procedure; this requires some administration as to how far various simultaneous instances of the procedures have progressed. For this reason, recursive definitions are very rare in everyday situations.

In language

[edit]Linguist Noam Chomsky, among many others, has argued that the lack of an upper bound on the number of grammatical sentences in a language, and the lack of an upper bound on grammatical sentence length (beyond practical constraints such as the time available to utter one), can be explained as the consequence of recursion in natural language.[4][5]

This can be understood in terms of a recursive definition of a syntactic category, such as a sentence. A sentence can have a structure in which what follows the verb is another sentence: Dorothy thinks witches are dangerous, in which the sentence witches are dangerous occurs in the larger one. So a sentence can be defined recursively (very roughly) as something with a structure that includes a noun phrase, a verb, and optionally another sentence. This is really just a special case of the mathematical definition of recursion.[clarification needed]

This provides a way of understanding the creativity of language—the unbounded number of grammatical sentences—because it immediately predicts that sentences can be of arbitrary length: Dorothy thinks that Toto suspects that Tin Man said that.... There are many structures apart from sentences that can be defined recursively, and therefore many ways in which a sentence can embed instances of one category inside another.[6] Over the years, languages in general have proved amenable to this kind of analysis.

The generally accepted idea that recursion is an essential property of human language has been challenged by Daniel Everett on the basis of his claims about the Pirahã language. Andrew Nevins, David Pesetsky and Cilene Rodrigues are among many who have argued against this.[7] Literary self-reference can in any case be argued to be different in kind from mathematical or logical recursion.[8]

Recursion plays a crucial role not only in syntax, but also in natural language semantics. The word and, for example, can be construed as a function that can apply to sentence meanings to create new sentences, and likewise for noun phrase meanings, verb phrase meanings, and others. It can also apply to intransitive verbs, transitive verbs, or ditransitive verbs. In order to provide a single denotation for it that is suitably flexible, and is typically defined so that it can take any of these different types of meanings as arguments. This can be done by defining it for a simple case in which it combines sentences, and then defining the other cases recursively in terms of the simple one.[9]

A recursive grammar is a formal grammar that contains recursive production rules.[10]

Recursive humor

[edit]Recursion is sometimes used humorously in computer science, programming, philosophy, or mathematics textbooks, generally by giving a circular definition or self-reference, in which the putative recursive step does not get closer to a base case, but instead leads to an infinite regress. It is not unusual for such books to include a joke entry in their glossary along the lines of:

- Recursion, see Recursion.[11]

A variation is found on page 269 in the index of some editions of Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie's book The C Programming Language; the index entry recursively references itself ("recursion 86, 139, 141, 182, 202, 269"). Early versions of this joke can be found in Let's talk Lisp by Laurent Siklóssy (published by Prentice Hall PTR on December 1, 1975, with a copyright date of 1976) and in Software Tools by Kernighan and Plauger (published by Addison-Wesley Professional on January 11, 1976). The joke also appears in The UNIX Programming Environment by Kernighan and Pike. It did not appear in the first edition of The C Programming Language. The joke is part of the functional programming folklore and was already widespread in the functional programming community before the publication of the aforementioned books.[12][13]

Another joke is that "To understand recursion, you must understand recursion."[11] In the English-language version of the Google web search engine, when a search for "recursion" is made, the site suggests "Did you mean: recursion."[14] An alternative form is the following, from Andrew Plotkin: "If you already know what recursion is, just remember the answer. Otherwise, find someone who is standing closer to Douglas Hofstadter than you are; then ask him or her what recursion is."

Recursive acronyms are other examples of recursive humor. PHP, for example, stands for "PHP Hypertext Preprocessor", WINE stands for "WINE Is Not an Emulator", GNU stands for "GNU's not Unix", and SPARQL denotes the "SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language".

In mathematics

[edit]

Recursively defined sets

[edit]Example: the natural numbers

[edit]The canonical example of a recursively defined set is given by the natural numbers:

- 0 is in

- if n is in , then n + 1 is in

- The set of natural numbers is the smallest set satisfying the previous two properties.

In mathematical logic, the Peano axioms (or Peano postulates or Dedekind–Peano axioms), are axioms for the natural numbers presented in the 19th century by the German mathematician Richard Dedekind and by the Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano. The Peano Axioms define the natural numbers referring to a recursive successor function and addition and multiplication as recursive functions.

Example: Proof procedure

[edit]Another interesting example is the set of all "provable" propositions in an axiomatic system that are defined in terms of a proof procedure which is inductively (or recursively) defined as follows:

- If a proposition is an axiom, it is a provable proposition.

- If a proposition can be derived from true reachable propositions by means of inference rules, it is a provable proposition.

- The set of provable propositions is the smallest set of propositions satisfying these conditions.

Finite subdivision rules

[edit]Finite subdivision rules are a geometric form of recursion, which can be used to create fractal-like images. A subdivision rule starts with a collection of polygons labelled by finitely many labels, and then each polygon is subdivided into smaller labelled polygons in a way that depends only on the labels of the original polygon. This process can be iterated. The standard `middle thirds' technique for creating the Cantor set is a subdivision rule, as is barycentric subdivision.

Functional recursion

[edit]A function may be recursively defined in terms of itself. A familiar example is the Fibonacci number sequence: F(n) = F(n − 1) + F(n − 2). For such a definition to be useful, it must be reducible to non-recursively defined values: in this case F(0) = 0 and F(1) = 1.

Proofs involving recursive definitions

[edit]Applying the standard technique of proof by cases to recursively defined sets or functions, as in the preceding sections, yields structural induction — a powerful generalization of mathematical induction widely used to derive proofs in mathematical logic and computer science.

Recursive optimization

[edit]Dynamic programming is an approach to optimization that restates a multiperiod or multistep optimization problem in recursive form. The key result in dynamic programming is the Bellman equation, which writes the value of the optimization problem at an earlier time (or earlier step) in terms of its value at a later time (or later step).

The recursion theorem

[edit]In set theory, this is a theorem guaranteeing that recursively defined functions exist. Given a set X, an element a of X and a function f: X → X, the theorem states that there is a unique function (where denotes the set of natural numbers including zero) such that

for any natural number n.

Dedekind was the first to pose the problem of unique definition of set-theoretical functions on by recursion, and gave a sketch of an argument in the 1888 essay "Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen?" [15]

Proof of uniqueness

[edit]Take two functions and such that:

where a is an element of X.

It can be proved by mathematical induction that F(n) = G(n) for all natural numbers n:

- Base Case: F(0) = a = G(0) so the equality holds for n = 0.

- Inductive Step: Suppose F(k) = G(k) for some . Then F(k + 1) = f(F(k)) = f(G(k)) = G(k + 1).

- Hence F(k) = G(k) implies F(k + 1) = G(k + 1).

By induction, F(n) = G(n) for all .

In computer science

[edit]A common method of simplification is to divide a problem into subproblems of the same type. As a computer programming technique, this is called divide and conquer and is key to the design of many important algorithms. Divide and conquer serves as a top-down approach to problem solving, where problems are solved by solving smaller and smaller instances. A contrary approach is dynamic programming. This approach serves as a bottom-up approach, where problems are solved by solving larger and larger instances, until the desired size is reached.

A classic example of recursion is the definition of the factorial function, given here in Python code:

def factorial(n):

if n > 0:

return n * factorial(n - 1)

else:

return 1

The function calls itself recursively on a smaller version of the input (n - 1) and multiplies the result of the recursive call by n, until reaching the base case, analogously to the mathematical definition of factorial.

Recursion in computer programming is exemplified when a function is defined in terms of simpler, often smaller versions of itself. The solution to the problem is then devised by combining the solutions obtained from the simpler versions of the problem. One example application of recursion is in parsers for programming languages. The great advantage of recursion is that an infinite set of possible sentences, designs or other data can be defined, parsed or produced by a finite computer program.

Recurrence relations are equations which define one or more sequences recursively. Some specific kinds of recurrence relation can be "solved" to obtain a non-recursive definition (e.g., a closed-form expression).

Use of recursion in an algorithm has both advantages and disadvantages. The main advantage is usually the simplicity of instructions. The main disadvantage is that the memory usage of recursive algorithms may grow very quickly, rendering them impractical for larger instances.

In biology

[edit]Shapes that seem to have been created by recursive processes sometimes appear in plants and animals, such as in branching structures in which one large part branches out into two or more similar smaller parts. One example is Romanesco broccoli.[16]

In the social sciences

[edit]Authors use the concept of recursivity to foreground the situation in which specifically social scientists find themselves when producing knowledge about the world they are always already part of.[17][18] According to Audrey Alejandro, “as social scientists, the recursivity of our condition deals with the fact that we are both subjects (as discourses are the medium through which we analyse) and objects of the academic discourses we produce (as we are social agents belonging to the world we analyse).”[19] From this basis, she identifies in recursivity a fundamental challenge in the production of emancipatory knowledge which calls for the exercise of reflexive efforts:

we are socialised into discourses and dispositions produced by the socio-political order we aim to challenge, a socio-political order that we may, therefore, reproduce unconsciously while aiming to do the contrary. The recursivity of our situation as scholars – and, more precisely, the fact that the dispositional tools we use to produce knowledge about the world are themselves produced by this world – both evinces the vital necessity of implementing reflexivity in practice and poses the main challenge in doing so.

— Audrey Alejandro, Alejandro (2021)

In business

[edit]Recursion is sometimes referred to in management science as the process of iterating through levels of abstraction in large business entities.[20] A common example is the recursive nature of management hierarchies, ranging from line management to senior management via middle management. It also encompasses the larger issue of capital structure in corporate governance.[21]

In art

[edit]

The Matryoshka doll is a physical artistic example of the recursive concept.[22]

Recursion has been used in paintings since Giotto's Stefaneschi Triptych, made in 1320. Its central panel contains the kneeling figure of Cardinal Stefaneschi, holding up the triptych itself as an offering.[23][24] This practice is more generally known as the Droste effect, an example of the Mise en abyme technique.

M. C. Escher's Print Gallery (1956) is a print which depicts a distorted city containing a gallery which recursively contains the picture, and so ad infinitum.[25]

In culture

[edit]The film Inception has colloquialized the appending of the suffix -ception to a noun to jokingly indicate the recursion of something.[26]

See also

[edit]- Corecursion – Type of algorithm in computer science

- Course-of-values recursion – Technique for defining number-theoretic functions by recursion

- Digital infinity – Term in theoretical linguistics

- A Dream Within a Dream (poem) – Poem by Edgar Allan Poe

- Droste effect – Recursive visual effect

- False awakening – Vivid and convincing dream about awakening from sleep

- Fixed point combinator – Higher-order function Y for which Y f = f (Y f)

- Infinite compositions of analytic functions – Mathematical theory about infinitely iterated function composition

- Infinite loop – Programming idiom

- Infinite regress – Philosophical problem

- Infinitism – Philosophical view that knowledge may be justified by an infinite chain of reasons

- Infinity mirror – Parallel mirrors reflecting each other

- Iterated function – Result of repeatedly applying a mathematical function

- Mathematical induction – Form of mathematical proof

- Mise en abyme – Technique of placing a copy of an image within itself, or a story within a story

- Reentrant (subroutine) – Concept in computer programming

- Self-reference – Sentence, idea or formula that refers to itself

- Spiegel im Spiegel – 1978 musical composition by Arvo Pärt

- Strange loop – Cycles going through a hierarchy

- Tail recursion – Subroutine call performed as final action of a procedure

- Tupper's self-referential formula – Formula that visually represents itself when graphed

- Turtles all the way down – Statement of infinite regress

References

[edit]- ^ Causey, Robert L. (2006). Logic, sets, and recursion (2nd ed.). Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 0-7637-3784-4. OCLC 62093042.

- ^ "Peano axioms | mathematics". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- ^ "Definition of RECURSIVE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- ^ Pinker, Steven (1994). The Language Instinct. William Morrow.

- ^ Pinker, Steven; Jackendoff, Ray (2005). "The faculty of language: What's so special about it?". Cognition. 95 (2): 201–236. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.116.7784. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2004.08.004. PMID 15694646. S2CID 1599505.

- ^ Nordquist, Richard. "What Is Recursion in English Grammar?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- ^ Nevins, Andrew; Pesetsky, David; Rodrigues, Cilene (2009). "Evidence and argumentation: A reply to Everett (2009)" (PDF). Language. 85 (3): 671–681. doi:10.1353/lan.0.0140. S2CID 16915455. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-06.

- ^ Drucker, Thomas (4 January 2008). Perspectives on the History of Mathematical Logic. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8176-4768-1.

- ^ Barbara Partee and Mats Rooth. 1983. In Rainer Bäuerle et al., Meaning, Use, and Interpretation of Language. Reprinted in Paul Portner and Barbara Partee, eds. 2002. Formal Semantics: The Essential Readings. Blackwell.

- ^ Nederhof, Mark-Jan; Satta, Giorgio (2002), "Parsing Non-recursive Context-free Grammars", Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL '02), Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 112–119, doi:10.3115/1073083.1073104.

- ^ a b Hunter, David (2011). Essentials of Discrete Mathematics. Jones and Bartlett. p. 494. ISBN 9781449604424.

- ^ Shaffer, Eric. "CS 173:Discrete Structures" (PDF). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ "Introduction to Computer Science and Programming in C; Session 8: September 25, 2008" (PDF). Columbia University. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ "recursion - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- ^ A. Kanamori, "In Praise of Replacement", pp.50--52. Bulletin of Symbolic Logic, vol. 18, no. 1 (2012). Accessed 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Picture of the Day: Fractal Cauliflower". 28 December 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Bourdieu, Pierre (1992). "Double Bind et Conversion". Pour Une Anthropologie Réflexive. Paris: Le Seuil.

- ^ Giddens, Anthony (1987). Social Theory and Modern Sociology. Polity Press.

- ^ Alejandro, Audrey (2021). "Reflexive discourse analysis: A methodology for the practice of reflexivity". European Journal of International Relations. 27 (1): 171. doi:10.1177/1354066120969789. ISSN 1354-0661. S2CID 229461433.

- ^ Riding, Allan; Haines, George H.; Thomas, Roland (1994). "The Canadian Small Business–Bank Interface: A Recursive Model". Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 18 (4). SAGE Journals: 5–24. doi:10.1177/104225879401800401.

- ^ Beer, Stafford (1972). Brain Of The Firm. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0471948391.

- ^ Tang, Daisy (March 2013). "CS240 -- Lecture Notes: Recursion". California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Archived from the original on 2018-03-17. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

More examples of recursion: Russian Matryoshka dolls. Each doll is made of solid wood or is hollow and contains another Matryoshka doll inside it.

- ^ "Giotto di Bondone and assistants: Stefaneschi triptych". The Vatican. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ Svozil, Karl (2018). Physical (A)Causality: Determinism, Randomness and Uncaused Events. Springer. p. 12. ISBN 9783319708157.

- ^ Cooper, Jonathan (5 September 2007). "Art and Mathematics". Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "-ception – The Rice University Neologisms Database". Rice University. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dijkstra, Edsger W. (1960). "Recursive Programming". Numerische Mathematik. 2 (1): 312–318. doi:10.1007/BF01386232. S2CID 127891023.

- Johnsonbaugh, Richard (2004). Discrete Mathematics. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-117686-7.

- Hofstadter, Douglas (1999). Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02656-2.

- Shoenfield, Joseph R. (2000). Recursion Theory. A K Peters Ltd. ISBN 978-1-56881-149-9.

- Causey, Robert L. (2001). Logic, Sets, and Recursion. Jones & Bartlett. ISBN 978-0-7637-1695-0.

- Cori, Rene; Lascar, Daniel; Pelletier, Donald H. (2001). Recursion Theory, Gödel's Theorems, Set Theory, Model Theory. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850050-6.

- Barwise, Jon; Moss, Lawrence S. (1996). Vicious Circles. Stanford Univ Center for the Study of Language and Information. ISBN 978-0-19-850050-6. - offers a treatment of corecursion.

- Rosen, Kenneth H. (2002). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications. McGraw-Hill College. ISBN 978-0-07-293033-7.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001). Introduction to Algorithms. Mit Pr. ISBN 978-0-262-03293-3.

- Kernighan, B.; Ritchie, D. (1988). The C programming Language. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-110362-7.

- Stokey, Nancy; Robert Lucas; Edward Prescott (1989). Recursive Methods in Economic Dynamics. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-75096-8.

- Hungerford (1980). Algebra. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-90518-1., first chapter on set theory.

External links

[edit]Recursion

View on GrokipediaDefinitions

Informal definition

Recursion is a fundamental concept in problem-solving and definition, characterized by a process that breaks down a complex task into simpler, self-similar subtasks until reaching a straightforward base case that can be directly resolved. This self-referential approach allows for elegant solutions to problems exhibiting inherent structure, such as hierarchical or fractal patterns, without explicitly outlining every step in advance. Unlike linear methods, recursion relies on the idea that understanding the whole emerges from grasping progressively smaller parts of the same kind.[4] A classic analogy for recursion is the Russian nesting doll, or Matryoshka, where each doll contains a slightly smaller version of itself inside, continuing until the tiniest doll is reached, which requires no further opening. This illustrates how a recursive process "unpacks" a problem layer by layer, handling each level by deferring to the next smaller instance, until the innermost, simplest case halts the progression. Similarly, consulting a dictionary to define a word often involves looking up terms that lead to further definitions, indirectly circling back through related concepts but eventually resolving through foundational entries, demonstrating recursion's indirect self-reference in everyday language use.[5][6] The notion of recursion traces back to ancient symbols of self-reference, such as the Ouroboros—a serpent devouring its own tail—depicted in Egyptian iconography around 1600 BCE and later adopted in Greek and alchemical traditions to signify eternal cycles and unity. In modern interpretations, this image evokes recursive processes through its equation of a function with its self-application, highlighting recursion's roots in intuitive ideas of perpetuity and closure long before formal mathematics.[7] While recursion emphasizes self-similarity and decomposition into identical subproblems, it complements iteration, which achieves repetition through explicit loops that execute a fixed block of instructions multiple times without self-calls. Both techniques enable repeated computation, but recursion naturally suits problems with nested structures, whereas iteration excels in sequential, non-hierarchical tasks, often making them interchangeable in practice with appropriate transformations.[8]Formal definitions

In mathematical logic and set theory, recursion is formally defined through mechanisms that ensure well-definedness via fixed points or inductive closures, providing a foundation for constructing functions and sets without circularity. These definitions rely on prerequisites such as partial orders and closure operators to guarantee existence and uniqueness. One standard formalization expresses recursion via fixed points of a functional derived from base operations. A function is recursively defined if it satisfies the equation for all , where and are given base functions, and is the least fixed point of the associated monotone functional in a suitable complete lattice of functions. This framework captures general recursive definitions by solving the implicit equation , ensuring the solution is the minimal element satisfying the recursion scheme under a pointwise order. For sets, an inductive definition constructs a recursively defined set as the smallest subset closed under specified operations. Formally, given a base set and a collection of finitary operations for each , is the intersection of all subsets such that and for every and , . This yields the least fixed point of the closure operator generated by and , often realized through transfinite iteration up to the first ordinal where stabilization occurs.[9] To prove properties of such recursive structures, Noetherian induction serves as a key formal tool, leveraging well-founded orders to establish claims by minimal counterexample elimination. On a poset that is Noetherian (every nonempty subset has a minimal element), a property holds for all if, for every , whenever holds for all , then holds; recursive structures induce such orders via construction depth or subterm relations, enabling proofs of invariance or termination.[10]Mathematics

Recursively defined sets

In set theory, particularly within the framework of Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms, recursively defined sets are constructed through a combination of base cases and closure rules, yielding the smallest set that satisfies these conditions. A base case specifies initial elements, while closure rules dictate how new elements are generated from existing ones, often via operations like union or power set. For instance, an inductive set is defined as one containing the empty set as a base and closed under the successor function , ensuring the set includes all elements obtainable by finite applications of these rules. This mechanism, formalized in the axiom of infinity, guarantees the existence of such infinite sets without requiring prior enumeration.[11][12] These recursive constructions play a crucial role in formalizing infinite structures, such as ordinals and trees, by enabling transfinite extensions beyond finite iterations. Ordinals, for example, are built recursively as transitive sets well-ordered by membership, where each ordinal consists precisely of all ordinals less than , starting from and closing under successors and limits. Similarly, the von Neumann hierarchy is defined by transfinite recursion: , (the power set), and for limit ordinals , . This hierarchical buildup stratifies the universe of sets by rank, allowing the representation of complex infinite objects like well-ordered trees without invoking unrestricted comprehension.[12] Unlike explicit definitions, which rely on direct enumeration or property-based comprehension for finite or simply describable sets, recursive definitions circumvent the need for complete listing, which is infeasible for uncountable or highly complex structures. Explicit approaches falter when sets grow transfinitely or involve operations without closed-form expressions, whereas recursion leverages well-foundedness to iteratively generate elements, ensuring consistency within axiomatic systems like ZFC. This distinction is essential for handling infinities, as recursive closure provides a controlled, paradox-free pathway to define sets that explicit methods cannot practically achieve.[11][12]Examples of recursive definitions

One prominent example of a recursive definition in mathematics is the construction of the natural numbers , which forms the foundation of arithmetic. This set is defined as the smallest collection containing the base element 0 and closed under the successor function , where for any . Formally, , ensuring that every natural number is either 0 or obtained by successive applications of to prior elements.[13] This recursive characterization aligns with the Peano axioms, providing a rigorous basis for defining operations like addition and multiplication on .[14] In formal logic, the set of provable theorems within a deductive system, such as propositional logic, is recursively defined to capture the notion of derivability. The base cases consist of a fixed set of axioms, such as the Hilbert-style axioms for implication and negation: (1) , (2) , (3) , and (4) . The recursive step applies the inference rule of modus ponens: if and are theorems, then is a theorem. Thus, the set of theorems is the smallest collection containing all axioms and closed under modus ponens, generating all derivable formulas from the base through finite iterations.[15] A classic illustration of recursion in sequences is the Fibonacci sequence, which arises in various combinatorial contexts. It is defined with initial conditions and , and the recursive rule for all integers . This generates the sequence 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, and so on, where each term depends on the two preceding ones, demonstrating how recursive definitions can produce infinite structures from finite base cases.[16]Functional recursion

In mathematics, functional recursion involves defining functions on domains such as the natural numbers through recursive equations that reference the function itself at simpler arguments, enabling the construction of complex mappings from basic operations.[4] This approach contrasts with iterative methods by building computations via self-referential calls, often formalized through specific schemas that ensure well-definedness on well-founded structures like the naturals.[4] Primitive recursive functions represent a foundational class of such functions, formalized by Kurt Gödel in 1931 as part of his work on formal systems, though the concept drew from earlier recursive definitions by Dedekind and Skolem.[4] They are generated from three initial functions—the constant zero function , the successor function , and the projection functions for —and closed under two operations: composition and primitive recursion.[4] Composition allows combining existing primitive recursive functions; if and are primitive recursive, then is as well.[4] The primitive recursion schema defines a new function and , where and are previously defined primitive recursive functions and denotes parameters.[4] Rózsa Péter in 1932 further analyzed their properties, coining the term "primitive recursive" and proving closure under additional operations like bounded minimization.[4] A canonical example is the addition function , defined by and , which applies the primitive recursion schema with and .[4] This builds addition from successor applications, illustrating how arithmetic operations emerge from recursive composition without unbounded search.[4] Functional recursion can be categorized as structural or generative based on how recursive calls relate to the input. Structural recursion follows the inductive structure of the domain, such as recursing on the predecessors of natural numbers or subtrees in a tree, ensuring each call processes a proper substructure until a base case.[4] In contrast, generative recursion produces new arguments for recursive calls that may not directly mirror the input's structure, often generating sequences or values through iterative deepening, as seen in searches or nested definitions.[4] This distinction highlights the flexibility of recursive schemas beyond simple induction, though generative forms risk non-termination if not carefully bounded.[4] The Ackermann function exemplifies a total recursive function outside the primitive recursive class, introduced by Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928 to demonstrate functions computable yet beyond primitive schemas.[4] Defined as , , and for natural numbers , it employs nested recursion where the inner call's result serves as the outer argument, yielding hyper-exponential growth that dominates all primitive recursive functions.[4] Péter in 1935 provided an equivalent formulation confirming its non-primitive recursive nature, as no primitive schema can capture its double-exponential escalation without violating closure bounds.[4]Proofs involving recursive definitions

Proofs involving recursive definitions require specialized induction techniques to establish properties of objects defined recursively, ensuring that the proofs align with the recursive structure to guarantee completeness and termination. These methods extend the principle of mathematical induction, adapting it to the inductive nature of the definitions themselves, and are essential for verifying correctness in mathematical structures like sequences, sets, and functions.[17] Structural induction is a proof technique used to demonstrate that a property holds for all elements of a recursively defined set, such as lists or trees, by exploiting the inductive clauses in the definition. The proof consists of a base case, verifying the property for the simplest elements (e.g., the empty list or single-node tree), and an inductive step, assuming the property holds for substructures and showing it extends to the larger structure formed by combining them. For instance, to prove that every binary tree with nodes has exactly edges, the base case confirms it for a single node (0 edges), and the inductive step assumes it for the left and right subtrees, then adds the connecting edge to verify the total. This method directly mirrors the recursive construction, ensuring the property propagates through all possible structures.[18][19] Complete induction, also known as strong induction, is particularly suited for proving properties of recursively defined sequences, where the value at step depends on all previous values. In this approach, the base cases are established for the initial terms, and the inductive step assumes the property holds for all to prove it for . A classic example is verifying the recursive definition of the factorial, where and for ; to prove , the base case holds for and , and assuming the product formula for all allows multiplication by to confirm it for . This method is powerful for sequences with dependencies spanning multiple prior terms, such as the Fibonacci sequence.[17][20] Well-founded relations provide a general framework for ensuring termination in recursive proofs, particularly when dealing with arbitrary partial orders rather than just natural numbers. A relation on a set is well-founded if every nonempty subset has a minimal element with respect to , equivalently, there are no infinite descending chains . In proofs, this principle allows induction over the relation: to show a property holds for all , verify whenever holds for all such that , starting from minimal elements. This guarantees termination for recursive definitions by preventing infinite regressions, as seen in ordinal arithmetic where well-foundedness of the membership relation ensures recursive constructions halt. The concept originates from set theory, where it underpins transfinite recursion without cycles.[21][22]The recursion theorem

The recursion theorem, also known as Kleene's fixed-point theorem, is a cornerstone of computability theory that guarantees the existence of self-referential indices for partial recursive functions. Formally, for any total recursive function , there exists an index such that , where denotes the -th partial recursive function in some standard enumeration of all partial recursive functions.[23] This result, first established by Stephen Kleene, enables the formal construction of recursive definitions that refer to their own computational descriptions, facilitating proofs of undecidability and incompleteness in arithmetic.[24] The proof of the recursion theorem relies on the s-m-n theorem (parametrization theorem), which states that for any recursive , there exists a total recursive such that .[23] To construct the fixed point, define a recursive applicator function by , and let be an index for the composition . Then, set , yielding , as required.[24] This self-application ensures the fixed-point equation holds without circularity, leveraging the effective indexing of recursive functions.Computer Science

Recursion in programming

In computer science, recursion refers to a programming technique where a function invokes itself to solve a problem by breaking it down into smaller instances of the same problem, ultimately reaching a base case that terminates the calls.[1] This approach mirrors functional recursion in mathematics, where functions are defined in terms of themselves, but adapts it to imperative and functional programming paradigms.[1] A classic example of recursion is the computation of the factorial of a non-negative integer n, denoted as n!, which equals the product of all positive integers up to n. The pseudocode for a recursive factorial function is as follows:function fact(n):

if n == 0:

return 1

else:

return n * fact(n - 1)

function fact(n):

if n == 0:

return 1

else:

return n * fact(n - 1)

Tail recursion and optimization

In tail recursion, the recursive call is the final operation performed by the function before it returns, with no subsequent computations required after the call completes. This structure allows the recursive invocation to directly return its result as the function's result, without needing to preserve the caller's state on the stack.[29] A classic example is a tail-recursive implementation of the factorial function, which uses an accumulator to track the running product:(define (tail-fact n acc)

(if (= n 0)

acc

(tail-fact (- n 1) (* acc n))))

(define (tail-fact n acc)

(if (= n 0)

acc

(tail-fact (- n 1) (* acc n))))

(tail-fact n 1), and the recursive call to tail-fact is the last action, passing the updated accumulator. This contrasts with a non-tail-recursive factorial, such as:

(define (fact n)

(if (= n 0)

1

(* n (fact (- n 1)))))

(define (fact n)

(if (= n 0)

1

(* n (fact (- n 1)))))

(* n ...) occurs after the recursive call returns, requiring the stack to maintain the pending operation and local state for each level.[30]

The key advantage of tail recursion lies in its space complexity: tail-recursive functions can achieve O(1) auxiliary space by reusing the current stack frame, whereas non-tail recursion typically requires O(n) space due to the growing call stack that stores return addresses and intermediate values for each recursive level. This difference becomes critical for deep recursion, where non-tail forms risk stack overflow, while tail forms simulate iteration without linear stack growth. For instance, converting the non-tail factorial to its tail-recursive counterpart, as shown above, transforms the O(n) space usage to O(1) by deferring the computation to the accumulator.[30]

Tail call optimization (TCO), also known as tail call elimination, is a compiler or interpreter technique that exploits this property by replacing the tail-recursive call with a jump to the function's entry point, effectively converting the recursion into an iterative loop and preventing stack accumulation. This optimization ensures that tail-recursive code runs in constant stack space, matching the efficiency of explicit iteration. In the Scheme programming language, proper tail recursion—defined as supporting an unbounded number of active tail calls without additional space—is a required feature of compliant implementations, as specified in the Revised^5 Report on Scheme (R5RS). The R5RS mandates that tail contexts, such as the last expression in a lambda body, trigger this behavior, enabling space-efficient recursive programming.[29][30]