Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

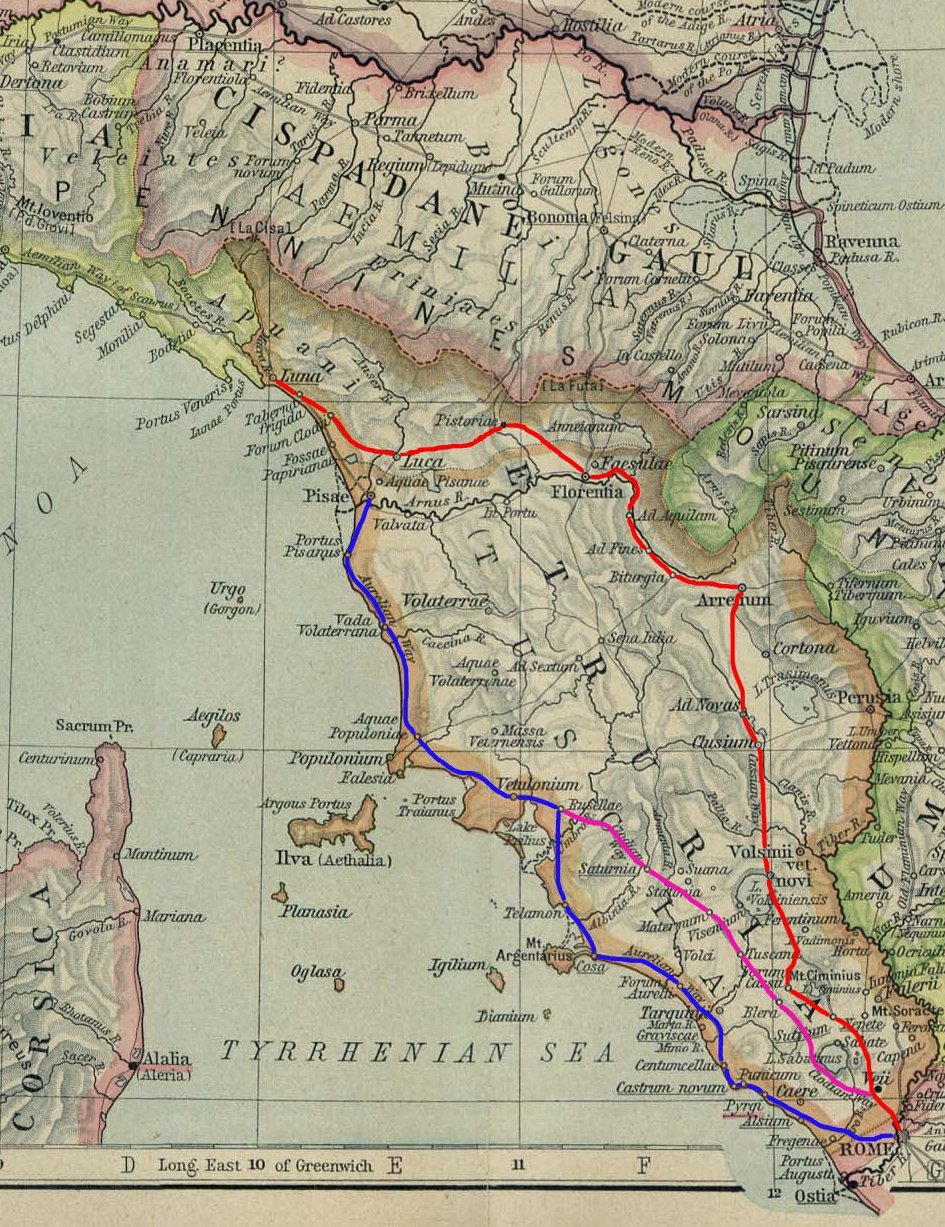

Via Aurelia

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

The Via Aurelia (lit. 'Aurelian Way') is a Roman road in Italy constructed in approximately 241 BC. The project was undertaken by Gaius Aurelius Cotta, who at that time was censor.[1] Cotta had a history of building roads for Rome, as he had overseen the construction of a military road in Sicily (as consul in 252 BC, during the First Punic War) connecting Agrigentum (modern Agrigento) and Panormus (modern Palermo).[2]

Background

[edit]In the middle Republic, a series of roads were built throughout Italy to serve the needs of Roman expansion, including swift army movements and reasonably quick communication with Roman colonies spread throughout Italy. There also was the unintended (but beneficial) consequence of an increase in trade among Italian cities and with Rome. The roads were standardized to 15 feet (4.6 m) wide allowing two chariots to pass, and distance was marked with milestones.[3]

The Via Aurelia was constructed as a part of this road construction campaign, which began in 312 BC with the building of the Via Appia. Other roads included in this construction period were the Viae Amerina (c. 231 BC), Flaminina, Clodia, Aemilia, Cassia, Valeria (c. 307 BC), and Caecilia (c. 283 BC).[4]

Route

[edit]The Via Aurelia crossed the Tiber by way of the bridge Pons Aemilius, then exited Rome from its western side. After the Emperor Aurelian built a wall around Rome (c. 270–273 CE), the Via Aurelia exited from the Porta Aurelia (gates). The road then ran about 25 miles (40 km) to Alsium on the Tyrrhenian coast, north along the coast to Vada Volaterrana, Cosa, and Pisae (modern-day Pisa). There the original length of the Via Aurelia terminated.[5]

This was an especially important route during the early and middle Republic because it linked Rome, Cosa, and Pisae. Cosa was an important colony and military outpost in Etruria, and Pisae was the only port between Genua and Rome. Consequently, it was an important naval base for the Romans in their wars against the Ligurians, Gauls and Carthaginians.[6]

The Via Aurelia later was extended by roughly 320 km (200 mi) in 109 BC by the Via Aemilia Scauri, constructed by M. Aemilius Scaurus. This road led to Dertona (modern Tortona), Placentia, Cremona, Aquilea, and Genua, from which travellers could proceed to Gallia Narbonensis (southern France) by way of the Via Postumia.[1]

This followed some rebuilding of the road by the same person during his consulship in 119 BC.[7]

By the time of the high Empire, travellers could go from Rome by way of the Via Aurelia across the Alps on the Via Julia Augusta to either northern France or Gades (modern Cádiz, Spain).[8]

The modern Strada Statale 1 Aurelia occupies the same route, and colloquially is still referred to as La Via Aurelia.

Roman bridges

[edit]There are the remains of several Roman bridges along the road, including the Cloaca di Porta San Clementino, Ponte del Diavolo, Primo Ponte, and the Secondo Ponte (the last three in Sta Marinella).[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Hornblower, Simon, & Antony Spawforth. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History. [New] ed. London: Cambridge University Press, 1970. Volume 7, p. 548 & 643

- ^ Via Aurelia: The Roman Empire's Lost Highway Archived 2009-06-05 at the Wayback Machine Smithsonian Magazine, June 2009

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History. [New] ed. Paris: Cambridge University Press, 1950. Volume 8, pg. 484.

- ^ Platner, Samuel Ball. A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1929. pg. 561.

- ^ Boatwright, Mary T., Daniel J. Gargola & Richard J.A. Talbert. A Brief History of the Romans. Oxford University Press, New York, US, 2006. pp. 48-49.

- ^ Fentress, E., 'Via Aurelia, Via Aemilia', Papers of the British School at Rome LII, 1984, pp. 72-76

- ^ Boumphrey, Geoffrey Maxwell. Along the Roman Roads. London: Allen & Unwin, 1935.

External links

[edit]- Samuel Ball Platner, Via Aurelia, from A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London: Oxford University Press, 1929).

- Joshua Hammer, Via Aurelia: The Roman Empire's Lost Highway, Smithsonian magazine, June 2009.

- Omnes Viae: Via Aurelia on the Tabula Peutingeriana