Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

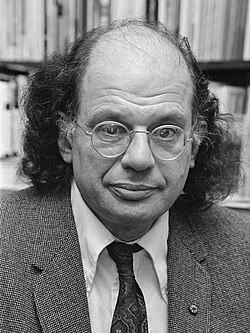

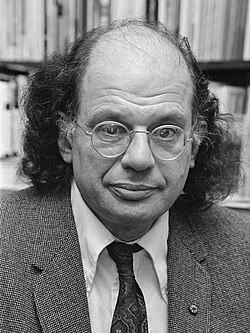

Allen Ginsberg

View on Wikipedia

Irwin Allen Ginsberg (/ˈɡɪnzbɜːrɡ/; June 3, 1926 – April 5, 1997) was an American poet and writer. As a student at Columbia University in the 1940s, he began friendships with Lucien Carr, William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, forming the core of the Beat Generation. He vigorously opposed militarism, economic materialism and sexual repression and he embodied various aspects of this counterculture with his views on drugs, sex, multiculturalism, hostility to bureaucracy and openness to Eastern religions.[1][2]

Key Information

Best known for his poem "Howl", Ginsberg denounced what he saw as the destructive forces of capitalism and conformity in the United States.[3][4] San Francisco police and US Customs seized copies of "Howl" in 1956 and a subsequent obscenity trial in 1957 attracted widespread publicity due to the poem's language and descriptions of heterosexual and homosexual sex at a time when sodomy laws made male homosexual acts a crime in every state.[5][6] The poem reflected Ginsberg's own sexuality and his relationships with a number of men, including Peter Orlovsky, his lifelong partner.[7] Judge Clayton W. Horn ruled that "Howl" was not obscene, asking: "Would there be any freedom of press or speech if one must reduce his vocabulary to vapid innocuous euphemisms?".[8]

Ginsberg was a Buddhist who extensively studied Eastern religious disciplines. He lived modestly, buying his clothing in second-hand stores and residing in apartments in New York City's East Village.[9] One of his most influential teachers was Tibetan Buddhist Chögyam Trungpa, the founder of the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado.[10] At Trungpa's urging, Ginsberg and poet Anne Waldman started The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics there in 1974.[11]

For decades, Ginsberg was active in political protests across a range of issues from the Vietnam War to the war on drugs.[12] His poem "September on Jessore Road" drew attention to refugees fleeing the 1971 Bangladeshi genocide, exemplifying what literary critic Helen Vendler described as Ginsberg's persistent opposition to "imperial politics" and the "persecution of the powerless".[13] His collection The Fall of America shared the annual National Book Award for Poetry in 1974.[14] In 1979, he received the National Arts Club gold medal and was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.[15] He was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 1995 for his book Cosmopolitan Greetings: Poems 1986–1992.[16]

Biography

[edit]Early life and family

[edit]Ginsberg was born into a Jewish[17] family in Newark, New Jersey, and grew up in nearby Paterson.[18] He was the second son of Louis Ginsberg, also born in Newark, a schoolteacher and published poet, and the former Naomi Levy, born in Nevel (Russia) and a fervent Marxist.[19]

As a teenager, Ginsberg began to write letters to The New York Times about political issues, such as World War II and workers' rights.[20] He published his first poems in the Paterson Morning Call.[21] While in high school, Ginsberg became interested in the works of Walt Whitman, inspired by his teacher's passionate reading.[22] In 1943, Ginsberg graduated from Eastside High School and briefly attended Montclair State College before entering Columbia University on a scholarship from the Young Men's Hebrew Association of Paterson. Ginsberg intended to study law at Columbia but later changed his major to literature.[19]

In 1945, he joined the Merchant Marine to earn money to continue his education at Columbia.[23] While at Columbia, Ginsberg contributed to the Columbia Review literary journal, the Jester humor magazine, won the Woodberry Poetry Prize, served as president of the Philolexian Society (literary and debate group), and joined Boar's Head Society (poetry society).[22][24] He was a resident of Hartley Hall, where other Beat Generation poets such as Jack Kerouac and Herbert Gold also lived.[25][26] Ginsberg has stated that he considered his required freshman seminar in Great Books, taught by Lionel Trilling, to be his favorite Columbia course. In 1948, he graduated from Columbia with a B.A in English and American Literature.[27]

According to The Poetry Foundation, Ginsberg spent several months in a mental institution after he pleaded insanity during a hearing. He was allegedly being prosecuted for harboring stolen goods in his dorm room. It was noted that the stolen property was not his, but belonged to an acquaintance.[28] Ginsberg also took part in public readings at the Episcopal St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery, which would later hold a memorial service for him after his death.[29][30]

Relationship with his parents

[edit]Ginsberg referred to his parents in a 1985 interview as "old-fashioned delicatessen philosophers".[18] His mother was also an active member of the Communist Party and took Ginsberg and his brother Eugene to party meetings. Ginsberg later said that his mother "made up bedtime stories that all went something like: 'The good king rode forth from his castle, saw the suffering workers and healed them.'"[20] Of his father Ginsberg said: "My father would go around the house either reciting Emily Dickinson and Longfellow under his breath or attacking T. S. Eliot for ruining poetry with his 'obscurantism.' I grew suspicious of both sides."[18]

Ginsberg's mother, Naomi Ginsberg, had schizophrenia which often manifested as paranoid delusions, disordered thinking and multiple suicide attempts.[31] She would claim, for example, that the president had implanted listening devices in their home and that her mother-in-law was trying to kill her.[32][33] Her suspicion of those around her caused Naomi to draw closer to Allen as a child, who she called her "little pet".[34] She also tried to kill herself by slitting her wrists and was soon taken to Greystone, a mental hospital; she would spend much of Ginsberg's youth in mental hospitals.[35][36] His experiences with his mother and her mental illness, including accompanying her on a visit to her therapist, were a major inspiration for his two major works, "Howl" and his long autobiographical poem "Kaddish for Naomi Ginsberg (1894–1956)".[37]

Ginsberg received a letter from his mother after her death responding to a copy of "Howl" he had sent her. It admonished Ginsberg to be good and stay away from drugs; she says, "The key is in the window, the key is in the sunlight at the window—I have the key—Get married Allen don't take drugs—the key is in the bars, in the sunlight in the window."[38] In a letter she wrote to Ginsberg's brother Eugene, she said, "God's informers come to my bed, and God himself I saw in the sky. The sunshine showed too, a key on the side of the window for me to get out. The yellow of the sunshine, also showed the key on the side of the window."[39] These letters and the absence of a facility to recite kaddish inspired Ginsberg to write "Kaddish", which makes references to many details from Naomi's life, Ginsberg's experiences with her, and the letter, including the lines "the key is in the light" and "the key is in the window."[40]

New York Beats

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

In Ginsberg's first year at Columbia he met fellow undergraduate Lucien Carr, who introduced him to a number of future Beat writers, including Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and John Clellon Holmes. They bonded, because they saw in one another an excitement about the potential of American youth, a potential that existed outside the strict conformist confines of post–World War II, McCarthy-era America.[41] Ginsberg and Carr talked excitedly about a "New Vision" (a phrase adapted from Yeats' "A Vision"), for literature and America. Carr also introduced Ginsberg to Neal Cassady, for whom Ginsberg had a long infatuation.[42] In the first chapter of his 1957 novel On the Road Kerouac described the meeting between Ginsberg and Cassady.[43] Kerouac saw them as the dark (Ginsberg) and light (Cassady) side of their "New Vision", a perception stemming partly from Ginsberg's association with communism, of which Kerouac had become increasingly distrustful. Though Ginsberg was never a member of the Communist Party, Kerouac named him "Carlo Marx" in On the Road. This was a source of strain in their relationship.[22]

Also, in New York, Ginsberg met Gregory Corso in the Pony Stable Bar. Corso, recently released from prison, was supported by the Pony Stable patrons and was writing poetry there the night of their meeting. Ginsberg claims he was immediately attracted to Corso, who was straight, but understood homosexuality after three years in prison. Ginsberg was even more struck by reading Corso's poems, realizing Corso was "spiritually gifted." Ginsberg introduced Corso to the rest of his inner circle. In their first meeting at the Pony Stable, Corso showed Ginsberg a poem about a woman who lived across the street from him and sunbathed naked in the window. Amazingly, the woman happened to be Ginsberg's girlfriend that he was living with during one of his forays into heterosexuality. Ginsberg took Corso over to their apartment. There the woman proposed sex with Corso, who was still very young and fled in fear. Ginsberg introduced Corso to Kerouac and Burroughs and they began to travel together. Ginsberg and Corso remained lifelong friends and collaborators.[44][additional citation(s) needed]

Shortly after this period in Ginsberg's life, he became romantically involved with Elise Nada Cowen after meeting her through Alex Greer, a philosophy professor at Barnard College whom she had dated for a while during the burgeoning Beat generation's period of development. As a Barnard student, Elise Cowen extensively read the poetry of Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, when she met Joyce Johnson and Leo Skir, among other Beat players.[citation needed] As Cowen had felt a strong attraction to darker poetry most of the time, Beat poetry seemed to provide an allure to what suggests a shadowy side of her persona. While at Barnard, Cowen earned the nickname "Beat Alice" as she had joined a small group of anti-establishment artists and visionaries known to outsiders as beatniks, and one of her first acquaintances at the college was the beat poet Joyce Johnson who later portrayed Cowen in her books, including "Minor Characters" and Come and Join the Dance, which expressed the two women's experiences in the Barnard and Columbia Beat community.[citation needed] Through his association with Elise Cowen, Ginsberg discovered that they shared a mutual friend, Carl Solomon, to whom he later dedicated his most famous poem "Howl." This poem is considered an autobiography of Ginsberg up to 1955, and a brief history of the Beat Generation through its references to his relationship to other Beat artists of that time.[citation needed]

The "Blake vision"

[edit]In 1948, in an apartment in East Harlem, Ginsberg experienced an auditory hallucination while masturbating and reading the poetry of William Blake,[45] which he later referred to as his "Blake vision". Ginsberg claimed to have heard the voice of God—also described as the "voice of the Ancient of Days"—or of Blake himself reading "Ah! Sun-flower", "The Sick Rose" and "The Little Girl Lost". The experience lasted several days, with him believing that he had witnessed the interconnectedness of the universe; Ginsberg recounted that after looking at latticework on the fire escape of the apartment and then at the sky, he intuited that one had been crafted by human beings, while the other had been crafted by itself.[46] He explained that this hallucination was not inspired by drug use, but said he sought to recapture the feeling of interconnectedness later with various drugs.[22] Later, in 1955, he referenced his "Blake vision" in his poem "Sunflower Sutra", saying "—I rushed up enchanted—it was my first sunflower, memories of Blake—my visions—".[47]

San Francisco Renaissance

[edit]Ginsberg moved to San Francisco during the 1950s. Before Howl and Other Poems was published in 1956 by City Lights, he worked as a market researcher.[48]

In 1954, in San Francisco, Ginsberg met Peter Orlovsky (1933–2010), with whom he fell in love and who remained his lifelong partner.[22] Selections from their correspondence have been published.[49]

Also in San Francisco, Ginsberg met members of the San Francisco Renaissance (James Broughton, Robert Duncan, Madeline Gleason and Kenneth Rexroth) and other poets who would later be associated with the Beat Generation in a broader sense. Ginsberg's mentor William Carlos Williams wrote an introductory letter to San Francisco Renaissance figurehead Kenneth Rexroth, who then introduced Ginsberg into the San Francisco poetry scene.[50] There, Ginsberg also met three budding poets and Zen enthusiasts who had become friends at Reed College: Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Lew Welch. In 1959, along with poets John Kelly, Bob Kaufman, A. D. Winans, and William Margolis, Ginsberg was one of the founders of the Beatitude poetry magazine.

Wally Hedrick—a painter and co-founder of the Six Gallery—approached Ginsberg in mid-1955 and asked him to organize a poetry reading at the Six Gallery. At first, Ginsberg refused, but once he had written a rough draft of "Howl," he changed his "fucking mind," as he put it.[41] Ginsberg advertised the event as "Six Poets at the Six Gallery." One of the most important events in Beat mythos, known simply as "The Six Gallery reading" took place on October 7, 1955.[51] The event, in essence, brought together the East and West Coast factions of the Beat Generation. Of more personal significance to Ginsberg, the reading that night included the first public presentation of "Howl," a poem that brought worldwide fame to Ginsberg and to many of the poets associated with him. An account of that night can be found in Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums, describing how change was collected from audience members to buy jugs of wine, and Ginsberg reading passionately, drunken, with arms outstretched.

Ginsberg's principal work, "Howl", is well known for its opening line: "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked [...]." "Howl" was considered scandalous at the time of its publication, because of the rawness of its language. Shortly after its 1956 publication by San Francisco's City Lights Bookstore, it was banned for obscenity. The ban became a cause célèbre among defenders of the First Amendment, and was later lifted, after Judge Clayton W. Horn declared the poem to possess redeeming artistic value.[22] Ginsberg and Shig Murao, the City Lights manager who was jailed for selling "Howl", became lifelong friends.[52]

Biographical references in "Howl"

[edit]Ginsberg claimed at one point that all of his work was an extended biography (like Kerouac's Duluoz Legend). "Howl" is not only a biography of Ginsberg's experiences before 1955, but also a history of the Beat Generation. Ginsberg also later claimed that at the core of "Howl" were his unresolved emotions about his schizophrenic mother. Though "Kaddish" deals more explicitly with his mother, "Howl" in many ways is driven by the same emotions. "Howl" chronicles the development of many important friendships throughout Ginsberg's life. He begins the poem with "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness", which sets the stage for Ginsberg to describe Cassady and Solomon, immortalizing them into American literature.[41] This madness was the "angry fix" that society needed to function—madness was its disease. In the poem, Ginsberg focused on "Carl Solomon! I'm with you in Rockland", and, thus, turned Solomon into an archetypal figure searching for freedom from his "straightjacket". Though references in most of his poetry reveal much about his biography, his relationship to other members of the Beat Generation, and his own political views, "Howl," his most famous poem, is still perhaps the best place to start.[citation needed]

To Paris and the "Beat Hotel", Tangier and India

[edit]In 1957, Ginsberg surprised the literary world by abandoning San Francisco. After a spell in Morocco, he and Peter Orlovsky joined Gregory Corso in Paris. Corso introduced them to a shabby lodging house above a bar at 9 rue Gît-le-Cœur that was to become known as the Beat Hotel. They were soon joined by Burroughs and others. It was a productive, creative time for all of them. There, Ginsberg began his epic poem "Kaddish", Corso composed Bomb and Marriage, and Burroughs (with help from Ginsberg and Corso) put together Naked Lunch from previous writings. This period was documented by the photographer Harold Chapman, who moved in at about the same time, and took pictures constantly of the residents of the "hotel" until it closed in 1963. During 1962–1963, Ginsberg and Orlovsky travelled extensively across India, living half a year at a time in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Benares (Varanasi). On his road to India he stayed two months in Athens ( August 29, 1961 – October 31, 1961) where he visited various sites such as Delphi, Mycines, Crete, and then continued his journey to Israel, Kenya and finally India.[53] Also during this time, he formed friendships with some of the prominent young Bengali poets of the time including Shakti Chattopadhyay and Sunil Gangopadhyay. Ginsberg had several political connections in India; most notably Pupul Jayakar who helped him extend his stay in India when the authorities were eager to expel him.

England and the International Poetry Incarnation

[edit]In May 1965, Ginsberg arrived in London, and offered to read anywhere for free.[54] Shortly after his arrival, he gave a reading at Better Books, which was described by Jeff Nuttall as "the first healing wind on a very parched collective mind."[54] Tom McGrath wrote: "This could well turn out to have been a very significant moment in the history of England—or at least in the history of English Poetry."[55]

Soon after the bookshop reading, plans were hatched for the International Poetry Incarnation,[55] which was held at the Royal Albert Hall in London on June 11, 1965. The event attracted an audience of 7,000, who heard readings and live and tape performances by a wide variety of figures, including Ginsberg, Adrian Mitchell, Alexander Trocchi, Harry Fainlight, Anselm Hollo, Christopher Logue, George MacBeth, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael Horovitz, Simon Vinkenoog, Spike Hawkins and Tom McGrath. The event was organized by Ginsberg's friend, the filmmaker Barbara Rubin.[56][57]

Peter Whitehead documented the event on film and released it as Wholly Communion. A book featuring images from the film and some of the poems that were performed was also published under the same title by Lorrimer in the UK and Grove Press in US.

Continuing literary activity

[edit]

Though the term "Beat" is most accurately applied to Ginsberg and his closest friends (Corso, Orlovsky, Kerouac, Burroughs, etc.), the term "Beat Generation" has become associated with many of the other poets Ginsberg met and became friends with in the late 1950s and early 1960s. A key feature of this term seems to be a friendship with Ginsberg. Friendship with Kerouac or Burroughs might also apply, but both writers later strove to disassociate themselves from the name "Beat Generation." Part of their dissatisfaction with the term came from the mistaken identification of Ginsberg as the leader. Ginsberg never claimed to be the leader of a movement. He claimed that many of the writers with whom he had become friends in this period shared many of the same intentions and themes. Some of these friends include: David Amram, Bob Kaufman; Diane di Prima; Jim Cohn; poets associated with the Black Mountain College such as Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and Denise Levertov; poets associated with the New York School such as Frank O'Hara and Kenneth Koch. LeRoi Jones before he became Amiri Baraka, who, after reading "Howl", wrote a letter to Ginsberg on a sheet of toilet paper. Baraka's independent publishing house Totem Press published Ginsberg's early work.[58][additional citation(s) needed] Through a party organized by Baraka, Ginsberg was introduced to Langston Hughes while Ornette Coleman played saxophone.[59]

Later in his life, Ginsberg formed a bridge between the beat movement of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s, befriending, among others, Timothy Leary, Ken Kesey, Hunter S. Thompson, and Bob Dylan. Ginsberg gave his last public reading at Booksmith, a bookstore in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, a few months before his death.[60] In 1993, Ginsberg visited the University of Maine at Orono to pay homage to the 90-year-old Carl Rakosi.[61]

Buddhism and Krishna

[edit]In 1950, Kerouac began studying Buddhism[62] and shared what he learned from Dwight Goddard's Buddhist Bible with Ginsberg.[62] Ginsberg first heard about the Four Noble Truths and such sutras as the Diamond Sutra at this time.[62] Ginsberg's endorsement helped establish the Krishna movement within New York's bohemian culture.[63]

Ginsberg's spiritual journey began early on with his spontaneous visions, and continued with an early trip to India with Gary Snyder.[62] Snyder had previously spent time in Kyoto to study at the First Zen Institute at Daitoku-ji Monastery.[62] At one point, Snyder chanted the Prajnaparamita, which in Ginsberg's words "blew my mind."[62] His interest piqued, Ginsberg traveled to meet the Dalai Lama as well as the Karmapa at Rumtek Monastery.[62] Continuing on his journey, Ginsberg met Dudjom Rinpoche in Kalimpong, who taught him: "If you see something horrible, don't cling to it, and if you see something beautiful, don't cling to it."[62]

After returning to the United States, a chance encounter on a New York City street with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (they both tried to catch the same cab),[64] a Kagyu and Nyingma Tibetan Buddhist master, led to Trungpa becoming his friend and lifelong teacher.[62] Ginsberg helped Trungpa and New York poet Anne Waldman in founding the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado.

Ginsberg was also involved with Krishnaism. He had started incorporating chanting the Hare Krishna mantra into his religious practice in the mid-1960s. After learning that A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the Hare Krishna movement in the Western world had rented a store front in New York, he befriended him, visiting him often and suggesting publishers for his books, and a fruitful relationship began. This relationship is documented by Satsvarupa dasa Goswami in his biographical account Srila Prabhupada Lilamrta. Ginsberg donated money, materials, and his reputation to help the Swami establish the first temple, and toured with him to promote his cause.[65]

Despite disagreeing with many of Bhaktivedanta Swami's required prohibitions, Ginsberg often sang the Hare Krishna mantra publicly as part of his philosophy[66] and declared that it brought a state of ecstasy.[67] He was glad that Bhaktivedanta Swami, an authentic swami from India, was now trying to spread the chanting in America. Along with other counterculture ideologists like Timothy Leary, Gary Snyder, and Alan Watts, Ginsberg hoped to incorporate Bhaktivedanta Swami and his chanting into the hippie movement, and agreed to take part in the Mantra-Rock Dance concert and to introduce the swami to the Haight-Ashbury hippie community.[66][68][nb 1]

On January 17, 1967, Ginsberg helped plan and organize a reception for Bhaktivedanta Swami at San Francisco International Airport, where fifty to a hundred hippies greeted the Swami, chanting Hare Krishna in the airport lounge with flowers in hands.[69][nb 2] To further support and promote Bhaktivedanta Swami's message and chanting in San Francisco, Allen Ginsberg agreed to attend the Mantra-Rock Dance, a musical event held in 1967 at the Avalon Ballroom by the San Francisco Hare Krishna temple. It featured some leading rock bands of the time: Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead, and Moby Grape, who performed there along with the Hare Krishna founder Bhaktivedanta Swami and donated proceeds to the Krishna temple. Ginsberg introduced Bhaktivedanta Swami to some three thousand hippies in the audience and led the chanting of the Hare Krishna mantra.[70][71][72]

Music and chanting were both important parts of Ginsberg's live delivery during poetry readings.[73] He often accompanied himself on a harmonium, and was often accompanied by a guitarist. It is believed that the Hindi and Buddhist poet Nagarjun had introduced Ginsberg to the harmonium in Banaras. According to Malay Roy Choudhury, Ginsberg refined his practice while learning from his relatives, including his cousin Savitri Banerjee.[74] When Ginsberg asked if he could sing a song in praise of Lord Krishna on William F. Buckley, Jr.'s TV show Firing Line on September 3, 1968, Buckley acceded and the poet chanted slowly as he played dolefully on a harmonium. According to Richard Brookhiser, an associate of Buckley's, the host commented that it was "the most unharried Krishna I've ever heard."[75]

At the 1967 Human Be-In in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and the 1970 Black Panther rally at Yale campus Allen chanted "Om" repeatedly over a sound system for hours on end.[76]

Ginsberg further brought mantras into the world of rock and roll when he recited the Heart Sutra in the song "Ghetto Defendant". The song appears on the 1982 album Combat Rock by British first wave punk band The Clash.

Ginsberg came in touch with the Hungryalist poets of Bengal, especially Malay Roy Choudhury, who introduced Ginsberg to the three fish with one head of Indian emperor Jalaluddin Mohammad Akbar. The three fish symbolised coexistence of all thought, philosophy, and religion.[77]

In spite of Ginsberg's attraction to Eastern religions, the journalist Jane Kramer argues that he, like Whitman, adhered to an "American brand of mysticism" that was "rooted in humanism and in a romantic and visionary ideal of harmony among men."[78]

The Allen Ginsberg Estate and Jewel Heart International partnered to present "Transforming Minds: Kyabje Gelek Rimpoche and Friends", a gallery and online exhibition of images of Gelek Rimpoche by Allen Ginsberg, a student with whom he had an "indissoluble bond," in 2021 at Tibet House US in New York City.[79][80] Fifty negatives from Ginsberg's Stanford University photo archive celebrated "the unique relationship between Allen and Rimpoche." The selection of never-before presented images, featuring great Tibetan masters including the Dalai Lama, Tibetologists, and students were "guided by Allen's extensive notes on the contact sheets and images he'd circled with the intention to print."[81]

Illness and death

[edit]In 1960, he was treated for a tropical disease, and it is speculated that he contracted hepatitis from an unsterilized needle administered by a doctor, which played a role in his death 37 years later.[82]

Ginsberg was a lifelong smoker, and though he tried to quit for health and religious reasons, his busy schedule in later life made it difficult, and he always returned to smoking.

In the 1970s, Ginsberg had two minor strokes which were first diagnosed as Bell's palsy, which gave him significant paralysis and stroke-like drooping of the muscles in one side of his face. Later in life, he also had constant minor ailments such as high blood pressure. Many of these symptoms were related to stress, but he never slowed down his schedule.[83]

Ginsberg won a 1974 National Book Award for The Fall of America (split with Adrienne Rich, Diving into the Wreck).[14]

In 1986, Ginsberg was awarded the Golden Wreath by the Struga Poetry Evenings International Festival in Macedonia, the second American poet to be so awarded since W. H. Auden. At Struga, Ginsberg met with the other Golden Wreath winners, Bulat Okudzhava and Andrei Voznesensky.

In 1989, Ginsberg appeared in Rosa von Praunheim's award-winning film Silence = Death about the fight of gay artists in New York City for AIDS-education and the rights of HIV infected people.[84]

In 1993, the French Minister of Culture appointed Ginsberg a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres.

Ginsberg continued to help his friends as much as he could: he gave money to Herbert Huncke out of his own pocket, regularly supplied neighbor Arthur Russell with an extension cord to power his home recording setup,[85][86] and housed a broke, drug-addicted Harry Smith.

With the exception of a special guest appearance at the NYU Poetry Slam on February 20, 1997, Ginsberg gave what is thought to be his last reading at The Booksmith in San Francisco on December 16, 1996.

After returning home from the hospital for the last time, where he had been unsuccessfully treated for congestive heart failure, Ginsberg continued making phone calls to say goodbye to nearly everyone in his address book. Some of the phone calls were sad and interrupted by crying, and others were joyous and optimistic.[87] Ginsberg continued to write through his final illness, with his last poem, "Things I'll Not Do (Nostalgias)", written on March 30.[88]

He died on April 5, 1997, surrounded by family and friends in his East Village loft in Manhattan, succumbing to liver cancer via complications of hepatitis at the age of 70.[19] Gregory Corso, Roy Lichtenstein, Patti Smith and others came by to pay their respects.[89] He was cremated, and his ashes were buried in his family plot in Gomel Chesed Cemetery in Newark.[90] He was survived by Orlovsky.

On May 14, 1998, a tribute event took place at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine attended by some 2,500 of Ginsberg's friends and fans.[91][92][93]

In August 1998, various writers, including Catfish McDaris, read at a gathering at Ginsberg's farm to honor Allen and the Beats.[94]

Good Will Hunting (released in December 1997) was dedicated to Ginsberg, as well as Burroughs, who died four months later.[95]

Social and political activism

[edit]Free speech

[edit]Ginsberg's willingness to talk about taboo subjects made him a controversial figure during the conservative 1950s, and a significant figure in the 1960s. In the mid-1950s, no reputable publishing company would even consider publishing Howl. At the time, such "sex talk" employed in Howl was considered by some to be vulgar or even a form of pornography, and could be prosecuted under law.[41] Ginsberg used phrases such as "cocksucker", "fucked in the ass", and "cunt" as part of the poem's depiction of different aspects of American culture. Numerous books that discussed sex were banned at the time, including Lady Chatterley's Lover.[41] The sex that Ginsberg described did not portray the sex between heterosexual married couples, or even longtime lovers. Instead, Ginsberg portrayed casual sex.[41] For example, in Howl, Ginsberg praises the man "who sweetened the snatches of a million girls." Ginsberg used gritty descriptions and explicit sexual language, pointing out the man "who lounged hungry and lonesome through Houston seeking jazz or sex or soup." In his poetry, Ginsberg also discussed the then-taboo topic of homosexuality. The explicit sexual language that filled Howl eventually led to an important trial on First Amendment issues. Ginsberg's publisher was brought up on charges for publishing pornography, and the outcome led to a judge going on record dismissing charges, because the poem carried "redeeming social importance,"[96] thus setting an important legal precedent. Ginsberg continued to broach controversial subjects throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. From 1970 to 1996, Ginsberg had a long-term affiliation with PEN American Center with efforts to defend free expression. When explaining how he approached controversial topics, he often pointed to Herbert Huncke: he said that when he first got to know Huncke in the 1940s, Ginsberg saw that he was sick from his heroin addiction, but at the time heroin was a taboo subject and Huncke was left with nowhere to go for help.[97]

Role in Vietnam War protests

[edit]

Ginsberg was a signer of the anti-war manifesto "A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority", circulated among draft resistors in 1967 by members of the radical intellectual collective RESIST. Other signers and RESIST members included Mitchell Goodman, Henry Braun, Denise Levertov, Noam Chomsky, William Sloane Coffin, Dwight Macdonald, Robert Lowell, and Norman Mailer.[98][99] In 1968, Ginsberg signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War,[100] and later became a sponsor of the War Tax Resistance project, which practiced and advocated tax resistance as a form of anti-war protest.[101]

He was present the night of the Tompkins Square Park riot (1988) and provided an eyewitness account to The New York Times.[102]

Relationship to communism

[edit]Ginsberg talked openly about his connections with communism and his admiration for past communist heroes and the labor movement at a time when the Red Scare and McCarthyism were still raging. He admired Fidel Castro and many other Marxist figures from the 20th century.[103][104] Ginsberg was a member of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.[105] In "America" (1956), Ginsberg writes: "America, I used to be a communist when I was a kid I'm not sorry". Biographer Jonah Raskin has claimed that, despite his often stark opposition to communist orthodoxy, Ginsberg held "his own idiosyncratic version of communism."[106] On the other hand, when Donald Manes, a New York City politician, publicly accused Ginsberg of being a member of the Communist Party, Ginsberg objected: "I am not, as a matter of fact, a member of the Communist party, nor am I dedicated to the overthrow of the U.S. government or any government by violence ... I must say that I see little difference between the armed and violent governments both Communist and Capitalist that I have observed".[107]

Ginsberg travelled to several communist countries to promote free speech. He claimed that communist countries, such as China, welcomed him because they thought he was an enemy of capitalism, but often turned against him when they saw him as a troublemaker. For example, in 1965 Ginsberg was deported from Cuba for publicly protesting the persecution of homosexuals.[108] The Cubans sent him to Czechoslovakia, where one week after being named the Král majálesu ("King of May",[109] a students' festivity, celebrating spring and student life), Ginsberg was arrested for alleged drug use and public drunkenness, and the security agency StB confiscated several of his writings, which they considered to be lewd and morally dangerous. Ginsberg was then deported from Czechoslovakia on May 7, 1965,[108][110] by order of the StB.[111] Václav Havel points to Ginsberg as an important inspiration.[112]

Gay rights

[edit]One contribution that is often considered his most significant and most controversial was his openness about homosexuality. Ginsberg was an early proponent of freedom for gay people. In 1943, he discovered within himself "mountains of homosexuality." He expressed this desire openly and graphically in his poetry.[113] He also struck a note for gay marriage by listing Peter Orlovsky, his lifelong companion, as his spouse in his Who's Who entry. Subsequent gay writers saw his frank talk about homosexuality as an opening to speak more openly and honestly about something often before only hinted at or spoken of in metaphor.[97]

In writing about sexuality in graphic detail and in his frequent use of language seen as indecent, he challenged—and ultimately changed—obscenity laws.[citation needed] He was a staunch supporter of others whose expression challenged obscenity laws (William S. Burroughs and Lenny Bruce, for example).[citation needed]

NAMBLA membership

[edit]Ginsberg was a supporter and member of the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA), a pedophilia and pederasty advocacy organization in the United States that works to abolish age of consent laws and legalize sexual relations between adults and children.[114][citation needed] Saying that he joined the organization "in defense of free speech",[115] Ginsberg stated: "Attacks on NAMBLA stink of politics, witchhunting for profit, humorlessness, vanity, anger and ignorance ... I'm a member of NAMBLA because I love boys too—everybody does, who has a little humanity".[116] In 1994, Ginsberg appeared in a documentary on NAMBLA called Chicken Hawk: Men Who Love Boys (playing on the gay male slang term 'chickenhawk'), in which he read a "graphic ode to youth".[114] He read his poem "Sweet Boy, Gimme Yr Ass" from the book Mind Breaths,[117] a collection of poems he called a "pederast rhapsody" that features graphic depictions of sex with boys.[118]

In her 2002 book Heartbreak, Andrea Dworkin claimed Ginsberg had ulterior motives for allying with NAMBLA:

In 1982, newspapers reported in huge headlines that the Supreme Court had ruled child pornography illegal. I was thrilled. I knew Allen would not be. I did think he was a civil libertarian. But, in fact, he was a pedophile. He did not belong to the North American Man/Boy Love Association out of some mad, abstract conviction that its voice had to be heard. He meant it. I take this from what Allen said directly to me, not from some inference I made. He was exceptionally aggressive about his right to fuck children and his constant pursuit of underage boys.[119]

In reference to his onetime friend Dworkin,[120] Ginsberg stated:

I've known Andrea since she was a student. I had a conversation with her when I said I've had many young affairs, [with those who were] 16, 17, or 18. I said, 'What are you going to do, send me to jail?' And she said, 'You should be shot.' The problem is, she was molested when she was young, and she hasn't recovered from the trauma, and she's taking it out on ordinary lovers.[121]

Recreational drugs

[edit]

Ginsberg talked often about drug use. He organized the New York City chapter of LeMar (Legalize Marijuana).[122] Throughout the 1960s he took an active role in the demystification of LSD, and, with Timothy Leary, worked to promote its common use. He remained for many decades an advocate of marijuana legalization, and, at the same time, warned his audiences against the hazards of tobacco in his Put Down Your Cigarette Rag (Don't Smoke): "Don't Smoke Don't Smoke Nicotine Nicotine No / No don't smoke the official Dope Smoke Dope Dope."[123]

CIA drug trafficking

[edit]Ginsberg worked closely with Alfred W. McCoy[124] on the latter's book The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia, which claimed that the CIA was knowingly involved in the production of heroin in the Golden Triangle of Burma, Thailand, and Laos.[125] In addition to working with McCoy, Ginsberg personally confronted Richard Helms, the director of the CIA in the 1970s, about the matter, but Helms denied that the CIA had anything to do with selling illegal drugs.[124][126] Ginsberg wrote many essays and articles, researching and compiling evidence of the CIA's alleged involvement in drug trafficking, but it took ten years, and the publication of McCoy's book in 1972, before anyone took him seriously.[124] In 1978, Ginsberg received a note from the chief editor of The New York Times, apologizing for not having taken his allegations seriously.[127] The political subject is dealt with in his song/poem "CIA Dope calypso". The United States Department of State responded to McCoy's initial allegations stating that they were "unable to find any evidence to substantiate them, much less proof."[128] Subsequent investigations by the Inspector General of the CIA,[129] United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs,[130] and United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, a.k.a. the Church Committee,[131] also found the charges to be unsubstantiated.

Work

[edit]Most of Ginsberg's very early poetry was written in formal rhyme and meter like that of his father, and of his idol William Blake. His admiration for the writing of Jack Kerouac inspired him to take poetry more seriously. In 1955, upon the advice of a psychiatrist, Ginsberg dropped out of the working world to devote his entire life to poetry.[132] Soon after, he wrote Howl, the poem that brought him and his Beat Generation contemporaries to national attention and allowed him to live as a professional poet for the rest of his life. Later in life, Ginsberg entered academia, teaching poetry as Distinguished Professor of English at Brooklyn College from 1986 until his death.[133]

Inspiration from friends

[edit]Ginsberg claimed throughout his life that his biggest inspiration was Kerouac's concept of "spontaneous prose." He believed literature should come from the soul without conscious restrictions. Ginsberg was much more prone to revise than Kerouac. For example, when Kerouac saw the first draft of Howl, he disliked the fact that Ginsberg had made editorial changes in pencil (transposing "negro" and "angry" in the first line, for example). Kerouac only wrote out his concepts of spontaneous prose at Ginsberg's insistence because Ginsberg wanted to learn how to apply the technique to his poetry.[22]

The inspiration for Howl was Ginsberg's friend, Carl Solomon, and Howl is dedicated to him. Solomon was a Dada and Surrealism enthusiast (he introduced Ginsberg to Artaud) who had bouts of clinical depression. Solomon wanted to commit suicide, but he thought a form of suicide appropriate to dadaism would be to go to a mental institution and demand a lobotomy. The institution refused, giving him many forms of therapy, including electroshock therapy. Much of the final section of the first part of Howl is a description of this.

Ginsberg used Solomon as an example of all those ground down by the machine of "Moloch." Moloch, to whom the second section is addressed, is a Levantine god to whom children were sacrificed. Ginsberg may have gotten the name from the Kenneth Rexroth poem "Thou Shalt Not Kill," a poem about the death of one of Ginsberg's heroes, Dylan Thomas. Moloch is mentioned a few times in the Torah and references to Ginsberg's Jewish background are frequent in his work. Ginsberg said the image of Moloch was inspired by peyote visions he had of the Francis Drake Hotel in San Francisco which appeared to him as a skull; he took it as a symbol of the city (not specifically San Francisco, but all cities).[134] Ginsberg later acknowledged in various publications and interviews that behind the visions of the Francis Drake Hotel were memories of the Moloch of Fritz Lang's film Metropolis (1927) and of the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward.[135] Moloch has subsequently been interpreted as any system of control, including the conformist society of post-World War II America, focused on material gain, which Ginsberg frequently blamed for the destruction of all those outside of societal norms.[22]

He also made sure to emphasize that Moloch is a part of humanity in multiple aspects, in that the decision to defy socially created systems of control—and therefore go against Moloch—is a form of self-destruction. Many of the characters Ginsberg references in Howl, such as Neal Cassady and Herbert Huncke, destroyed themselves through excessive substance abuse or a generally wild lifestyle. The personal aspects of Howl are perhaps as important as the political aspects. Carl Solomon, the prime example of a "best mind" destroyed by defying society, is associated with Ginsberg's schizophrenic mother: the line "with mother finally fucked" comes after a long section about Carl Solomon, and in Part III, Ginsberg says: "I'm with you in Rockland where you imitate the shade of my mother." Ginsberg later admitted that the drive to write Howl was fueled by sympathy for his ailing mother, an issue which he was not yet ready to deal with directly. He dealt with it directly with 1959's Kaddish,[22] which had its first public reading at a Catholic Worker Friday Night meeting, possibly due to its associations with Thomas Merton.[136]

Inspiration from mentors and idols

[edit]Ginsberg's poetry was strongly influenced by Modernism (most importantly the American style of Modernism pioneered by William Carlos Williams), Romanticism (specifically William Blake and John Keats), the beat and cadence of jazz (specifically that of bop musicians such as Charlie Parker), and his Kagyu Buddhist practice and Jewish background. He considered himself to have inherited the visionary poetic mantle handed down from the English poet and artist William Blake, the American poet Walt Whitman and the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca. The power of Ginsberg's verse, its searching, probing focus, its long and lilting lines, as well as its New World exuberance, all echo the continuity of inspiration that he claimed.[22][97][112]

He corresponded with William Carlos Williams, who was then in the middle of writing his epic poem Paterson about the industrial city near his home. After attending a reading by Williams, Ginsberg sent the older poet several of his poems and wrote an introductory letter. Most of these early poems were rhymed and metered and included archaic pronouns like "thee." Williams disliked the poems and told Ginsberg, "In this mode perfection is basic, and these poems are not perfect."[22][97][112]

Though he disliked these early poems, Williams loved the exuberance in Ginsberg's letter. He included the letter in a later part of Paterson. He encouraged Ginsberg not to emulate the old masters, but to speak with his own voice and the voice of the common American. From Williams, Ginsberg learned to focus on strong visual images, in line with Williams' own motto: "No ideas but in things." Studying Williams' style led to a tremendous shift from the early formalist work to a loose, colloquial free verse style. Early breakthrough poems include Bricklayer's Lunch Hour and Dream Record.[22][112]

Carl Solomon introduced Ginsberg to the work of Antonin Artaud (To Have Done with the Judgement of God and Van Gogh: The Man Suicided by Society), and Jean Genet (Our Lady of the Flowers). Philip Lamantia introduced him to other Surrealists and Surrealism continued to be an influence (for example, sections of "Kaddish" were inspired by André Breton's Free Union). Ginsberg claimed that the anaphoric repetition of Howl and other poems was inspired by Christopher Smart in such poems as Jubilate Agno. Ginsberg also claimed other more traditional influences, such as: Franz Kafka, Herman Melville, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Edgar Allan Poe, and Emily Dickinson.[22][97]

Ginsberg also made an intense study of haiku and the paintings of Paul Cézanne, from which he adapted a concept important to his work, which he called the Eyeball Kick. He noticed in viewing Cézanne's paintings that when the eye moved from one color to a contrasting color, the eye would spasm, or "kick." Likewise, he discovered that the contrast of two seeming opposites was a common feature in haiku. Ginsberg used this technique in his poetry, putting together two starkly dissimilar images: something weak with something strong, an artifact of high culture with an artifact of low culture, something holy with something unholy. The example Ginsberg most often used was "hydrogen jukebox" (which later became the title of a song cycle composed by Philip Glass with lyrics drawn from Ginsberg's poems). Another example is Ginsberg's observation on Bob Dylan during Dylan's hectic and intense 1966 electric-guitar tour, fueled by a cocktail of amphetamines,[137] opiates,[138] alcohol,[139] and psychedelics,[140] as a Dexedrine Clown. The phrases "eyeball kick" and "hydrogen jukebox" both show up in Howl, as well as a direct quote from Cézanne: "Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus".[97]

Inspiration from music

[edit]Allen Ginsberg also found inspiration in music. He frequently included music in his poetry, invariably composing his tunes on an old Indian harmonium, which he often played during his readings.[141] He wrote and recorded music to accompany William Blake's Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. He also recorded a handful of other albums. To create music for Howl and Wichita Vortex Sutra, he worked with the minimalist composer, Philip Glass.

Ginsberg worked with, drew inspiration from, and inspired artists such as Bob Dylan, The Clash, Patti Smith,[142] Phil Ochs, and The Fugs.[48] He worked with Dylan on various projects and maintained a friendship with him over many years.[143]

In 1981, Ginsberg recorded a song called "Birdbrain." He was backed by the Gluons, and the track was released as a single.[144] In 1996, he recorded a song co-written with Paul McCartney and Philip Glass, "The Ballad of the Skeletons",[145] which reached number 8 on the Triple J Hottest 100 for that year.

Style and technique

[edit]From the study of his idols and mentors and the inspiration of his friends—not to mention his own experiments—Ginsberg developed an individualistic style that's easily identified as Ginsbergian.[146] Ginsberg stated that Whitman's long line was a dynamic technique few other poets had ventured to develop further, and Whitman is also often compared to Ginsberg because their poetry sexualized aspects of the male form.[22][97][112]

Many of Ginsberg's early long line experiments contain some sort of anaphora, repetition of a "fixed base" (for example "who" in Howl, "America" in America) and this has become a recognizable feature of Ginsberg's style.[147] He said later this was a crutch because he lacked confidence; he did not yet trust "free flight."[148] In the 1960s, after employing it in some sections of Kaddish ("caw" for example) he, for the most part, abandoned the anaphoric form. "Latter-Day Beat" Bob Dylan is known for using anaphora, as in "Tangled Up in Blue" where the phrase, returned to at the end of every verse, takes the place of a chorus.[97][112]

Several of his earlier experiments with methods for formatting poems as a whole became regular aspects of his style in later poems. In the original draft of Howl, each line is in a "stepped triadic" format reminiscent of William Carlos Williams.[149] He abandoned the "stepped triadic" when he developed his long line although the stepped lines showed up later, most significantly in the travelogues of The Fall of America.[citation needed] Howl and Kaddish, arguably his two most important poems, are both organized as an inverted pyramid, with larger sections leading to smaller sections. In America, he also experimented with a mix of longer and shorter lines.[97][112]

Ginsberg's mature style made use of many specific, highly developed techniques, which he expressed in the "poetic slogans" he used in his Naropa teaching. Prominent among these was the inclusion of his unedited mental associations so as to reveal the mind at work ("First thought, best thought." "Mind is shapely, thought is shapely.") He preferred expression through carefully observed physical details rather than abstract statements ("Show, don't tell." "No ideas but in things.")[150] In these he carried on and developed traditions of modernism in writing that are also found in Kerouac and Whitman.

In Howl and in his other poetry, Ginsberg drew inspiration from the epic, free verse style of the 19th-century American poet Walt Whitman.[151] Both wrote passionately about the promise (and betrayal) of American democracy, the central importance of erotic experience, and the spiritual quest for the truth of everyday existence. J. D. McClatchy, editor of the Yale Review, called Ginsberg "the best-known American poet of his generation, as much a social force as a literary phenomenon." McClatchy added that Ginsberg, like Whitman, "was a bard in the old manner—outsized, darkly prophetic, part exuberance, part prayer, part rant. His work is finally a history of our era's psyche, with all its contradictory urges." McClatchy's barbed eulogies define the essential difference between Ginsberg ("a beat poet whose writing was [...] journalism raised by combining the recycling genius with a generous mimic-empathy, to strike audience-accessible chords; always lyrical and sometimes truly poetic") and Kerouac ("a poet of singular brilliance, the brightest luminary of a 'beat generation' he came to symbolise in popular culture [...] [though] in reality he far surpassed his contemporaries [...] Kerouac is an originating genius, exploring then answering—like Rimbaud a century earlier, by necessity more than by choice—the demands of authentic self-expression as applied to the evolving quicksilver mind of America's only literary virtuoso [...]").[18]

Honors

[edit]His collection The Fall of America shared the annual U.S. National Book Award for Poetry in 1974.[14]

Ginsberg won a 1974 National Book Award for The Fall of America (split with Adrienne Rich, Diving into the Wreck).[14]

In 1979, he received the National Arts Club gold medal and was inducted into the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.[15]

In 1986, Ginsberg was awarded the Golden Wreath by the Struga Poetry Evenings International Festival in Macedonia, the second American poet to be so awarded since W. H. Auden. At Struga, Ginsberg met with the other Golden Wreath winners, Bulat Okudzhava and Andrei Voznesensky.

In 1989, Ginsberg appeared in Rosa von Praunheim's award-winning film Silence = Death about the fight of gay artists in New York City for AIDS-education and the rights of HIV infected people.[84]

In 1993, the French Minister of Culture appointed Ginsberg a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres. Ginsberg was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 1995 for his book Cosmopolitan Greetings: Poems 1986–1992.[16] In 1993, he received a John Jay Award posthumously from Columbia.[152][153]

In 2014, Ginsberg was one of the inaugural honorees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighborhood noting LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields."[154][155][156]

Bibliography

[edit]- Howl and Other Poems (1956), ISBN 978-0-87286-017-9

- Kaddish and Other Poems (1961), ISBN 978-0-87286-019-3

- Empty Mirror: Early Poems (1961), ISBN 978-0-87091-030-2

- Reality Sandwiches (1963), ISBN 978-0-87286-021-6

- The Yage Letters (1963) – with William S. Burroughs

- Planet News (1968), ISBN 978-0-87286-020-9

- Indian Journals (1970), ISBN 0-8021-3475-0

- First Blues: Rags, Ballads & Harmonium Songs 1971 - 1974 (1975), ISBN 0-916190-05-6

- The Gates of Wrath: Rhymed Poems 1948–1951 (1972), ISBN 978-0-912516-01-1

- The Fall of America: Poems of These States (1973), ISBN 978-0-87286-063-6

- Iron Horse (1973)

- Allen Verbatim: Lectures on Poetry, Politics, Consciousness by Allen Ginsberg (1974), edited by Gordon Ball, ISBN 0-07-023285-7

- Sad Dust Glories: poems during work summer in woods (1975)

- Mind Breaths (1978), ISBN 978-0-87286-092-6

- Plutonian Ode: Poems 1977–1980 (1981), ISBN 978-0-87286-125-1

- Collected Poems 1947–1980 (1984), ISBN 978-0-06-015341-0. Republished with later material added as Collected Poems 1947-1997, New York, HarperCollins, 2006

- White Shroud Poems: 1980–1985 (1986), ISBN 978-0-06-091429-5

- Cosmopolitan Greetings Poems: 1986–1993 (1994)

- Howl Annotated (1995)

- Illuminated Poems (1996)

- Selected Poems: 1947–1995 (1996)

- Death and Fame: Poems 1993–1997 (1999)

- Deliberate Prose 1952–1995 (2000)

- Howl & Other Poems 50th Anniversary Edition (2006), ISBN 978-0-06-113745-7

- The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice: First Journals and Poems 1937-1952 (Da Capo Press, 2006)

- The Selected Letters of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder (Counterpoint, 2009)

- I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career: The Selected Correspondence of Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg, 1955–1997 (City Lights, 2015)

- The Best Minds of My Generation: A Literary History of the Beats (Grove Press, 2017)

Selected discography

[edit]- Howl And Other Poems (1959), Fantasy - 7006

- None (1965), with Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Andrei Voznesensky Lovebooks - LB0001

- Allen Ginsberg Reading at Better Books (1965), Better Books – 16156/57

- Reads Kaddish (A 20th Century American Ecstatic Narrative Poem) (1966), Atlantic – 4001

- The Ginsbergs At The ICA (1967), with Louise Ginsberg Saga Psyche – PSY 3000

- Consciousness & Practical Action (1967), Liberation Records – DL 16

- Challenge Seminar (1968), with Gregory Bateson and R. D. Laing Liberation Records – DL 23

- Ginsberg's Thing (1969), Transatlantic Records – TRA 192

- Songs Of Innocence And Experience (1970), MGM Records – FTS-3083, Verve Forecast – FTS-3083

- America Today! (The World's Greatest Poets Vol. I) (1971), with Gregory Corso and Lawrence Ferlinghetti CMS – CMS 617

- Gate, Two Evenings With Allen Ginsberg Vol.1 Songs (1980), Loft – LOFT 1001

- First Blues: Rags, Ballads & Harmonium Songs (1981), Folkways Records – FSS 37560

- First Blues (1983), John Hammond Records – W2X 37673

- Allen Ginsberg With Still Life (1983), with Still Life Local Anesthetic Records – LA LP-001

- Üvöltés (1987), with Hobo Krém – SLPM 37048

- The Lion For Real (1989), Great Jones – GJ-6004

- September On Jessore Road (1992), with the Mondriaan Quartet Soyo Records – 0001

- Cosmopolitan Greetings (1993), with George Gruntz Schweiz – MGB CD 9203, Migros-Genossenschafts-Bund – MGB CD 9203

- Hydrogen Jukebox (1993), with Philip Glass Elektra Nonesuch – 9 79286–2

- Allen Ginsberg: Material Wealth (Allen's voice in poems and songs 1956–1996)[157](2024)

See also

[edit]- The Life and Times of Allen Ginsberg (film)

- Category:Works by Allen Ginsberg

- Allen Ginsberg Live in London

- Hungry generation

- Howl (2010 film)

- LGBT culture in New York City

- List of LGBT people from New York City

- Central Park Be-In

- Trevor Carolan

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Burroughs by Howard Brookner

- List of peace activists

- Kill Your Darlings

- Jewish Buddhist

- American poetry

Notes

[edit]- ^ (from the "Houseboat Summit" panel discussion, Sausalito CA. February 1967)(Cohen 1991, p. 182):

Ginsberg: So what do you think of Swami Bhaktivedanta pleading for the acceptance of Krishna in every direction?

Snyder: Why, it's a lovely positive thing to say Krishna. It's a beautiful mythology and it's a beautiful practice.

Leary: Should be encouraged.

Ginsberg: He feels it's the one uniting thing. He feels a monopolistic unitary thing about it.

Watts: I'll tell you why I think he feels it. The mantras, the images of Krishna have in this culture no foul association [...] [W]hen somebody comes in from the Orient with a new religion which hasn't got any of [horrible] associations in our minds, all the words are new, all the rites are new, and yet, somehow it has feeling in it, and we can get with that, you see, and we can dig that! - ^ Addressing speculations that he was Allen Ginsberg's guru, Bhaktivedanta Swami answered a direct question in a public program, "Are you Allen Ginsberg's guru?" by saying, "I am nobody's guru. I am everybody's servant. Actually I am not even a servant; a servant of God is no ordinary thing." (Greene 2007, p. 85; Goswami 2011, pp. 196–97)

References

[edit]- ^ "Ginsberg, Allen (1926–1997)". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2007. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (2009). Howl, Kaddish and Other Poems. London: Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-14-119016-7.[page needed]

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (March 20, 2001). Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays 1952–1995. New York: HarperCollins. pp. xx–xxi. ISBN 978-0-06-093081-3.

- ^ "About Allen Ginsberg". PBS. December 29, 2002.

- ^ Jones, Derek, ed. (2015). Censorship: a world encyclopedia. Volume 1–4. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. p. 955. ISBN 978-1-135-00400-2. OCLC 910523065.

- ^ Collins, Ronald K. L.; Skover, David (2019). The People v. Ferlinghetti: The Fight to Publish Allen Ginsberg's Howl. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xi. ISBN 978-1-5381-2590-8.

- ^ Kramer, Jane (1968). Allen Ginsberg in America. New York: Random House. pp. 43–46. ISBN 978-1-299-40095-5.

- ^ de Grazia, Edward (March 2, 1993). Girls Lean Back Everywhere: The Law of Obscenity and the Assault on Genius. New York: Random House. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-679-74341-5.

- ^ "Allen Ginsberg Project – Bio". allenginsberg.org. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 440–44

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 454–55

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen, Deliberate Prose, the foreword by Edward Sanders, p. xxi.

- ^ Vendler, Helen (January 13, 1986), "Books: A Lifelong Poem Including History", The New Yorker, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d In 1993, Ginsberg visited the University of Maine at Orono for a conference, to pay homage to the 90-year-old great Carl Rakosi and to read poems as well. "National Book Awards – 1974". National Book Foundation. Retrieved April 7, 2012 (with acceptance speech by Ginsberg and essay by John Murillo from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog).

- ^ a b Miles 2001, p. 484

- ^ a b "The Pulitzer Prizes | Poetry". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ Pacernick, Gary. "Allen Ginsberg: An interview by Gary Pacernick" (February 10, 1996), The American Poetry Review, July/August 1997. "Yeah, I am a Jewish poet. I'm Jewish."

- ^ a b c d Hampton, Willborn (April 6, 1997). "Allen Ginsberg, Master Poet Of Beat Generation, Dies at 70". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Hampton, Wilborn (April 6, 1997). "Allen Ginsberg, Master Poet Of Beat Generation, Dies at 70". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ^ a b Jones, Bonesy. "Biographical Notes on Allen Ginsberg". Biography Project. Archived from the original on October 23, 2005. Retrieved October 20, 2005.

- ^ David S. Wills, "Allen Ginsberg's First Poem?"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Miles 2001

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (2008), The Letters of Allen Ginsberg. Philadelphia, Da Capo Press, p. 6.

- ^ "History". Columbia Review. May 22, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ "My generation – Columbia Spectator". Columbia Daily Spectator. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Krajicek, David J. (April 5, 2012). "Where Death Shaped the Beats". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Charters, Ann (July 2000) "Ginsberg's Life." American National Biography Online. American Council of Learned Societies.

- ^ Allen Ginsberg." Allen Ginsberg Biography. Poetry Foundation, 2014. Web. November 6, 2014.

- ^ "St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery". www.literarymanhattan.org. Archived from the original on March 12, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ Morgan, Bill (November 1997). Beat Generation in New York: A Walking Tour of Jack Kerouac's City. City Lights Books. ISBN 978-0-87286-325-5.

- ^ Hadda, Janet (2008). "Ginsberg in Hospital". American Imago. 65 (2): 229–59. ISSN 0065-860X. JSTOR 26305281.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 26

- ^ Hyde, Lewis and Ginsberg, Allen (1984) On the poetry of Allen Ginsberg. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06353-6. p. 421.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 18

- ^ Dittman, Michael J. (2007), Masterpieces of Beat literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-33283-5, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 13

- ^ Breslin, James (2003), "Allen Ginsberg: The Origins of Howl and Kaddish." in Poetry Criticism. David M. Galens (ed.). Vol. 47. Detroit: Gale.

- ^ Hyde, Lewis and Ginsberg, Allen (1984), On the poetry of Allen Ginsberg. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06353-6, pp. 426–27.

- ^ Morgan 2007, pp. 219–20

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (1961), Kaddish and Other Poems. Volume 2, Issue 14 of The Pocket Poets series. City Lights Books.

- ^ a b c d e f Raskin 2004

- ^ Barry Gifford, ed., As Ever: The Collected Correspondence of Allen Ginsberg & Neal Cassady.

- ^ Charters, Ann. "Allen Ginsberg's Life". Modern American Poetry website. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2005.

- ^ Miles 2001[page needed]

- ^ Morgan, Bill (2010). The Typewriter Is Holy: The Complete, Uncensored History of the Beat Generation. Simon and Schuster. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4165-9242-6.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (1984). "A Blake Experience". In Hyde, Lewis (ed.). On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg (2002 ed.). United States: The University of Michigan Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-472-09353-3.

- ^ "Sunflower Sutra". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved March 26, 2025.

- ^ a b Schumacher, Michael (January 27, 2002). "Allen Ginsberg Project".

- ^ Straight Hearts' Delight: Love Poems and Selected Letters, by Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, edited by Winston Leyland. Gay Sunshine Press, 1980, ISBN 0-917342-65-8.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (December 4, 2015) [December 4, 2015]. "How the Beats helped build San Francisco's progressive future". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Siegel, Robert (October 7, 2005). "Birth of the Beat Generation: 50 Years of 'Howl'". All Things Considered. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- ^ Ball, Gordon, "'Howl' and Other Victories: A friend remembers City Lights' Shig Murao", San Francisco Chronicle, November 28, 1999.

- ^ "Όταν ο ποιητής Άλεν Γκίνσμπεργκ επισκέφτηκε το Πέραμα. | LiFO". www.lifo.gr (in Greek). January 28, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Nuttall, J (1968) Bomb Culture MacGibbon & Kee, ISBN 0-261-62617-5

- ^ a b Fountain, N: Underground: the London alternative press, 1966–1974, p. 16. Taylor & Francis, 1988 ISBN 0-415-00728-3.

- ^ Hale, Peter (March 31, 2014). "Barbara Rubin (1945–1980)". The Allen Ginsberg Project.

- ^ Osterweil, Ara (2010). "Queer Coupling, or The Stain of the Bearded Woman" (PDF). araosterweil.com. Wayne State University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ "Amiri Baraka papers, 1945–2015". www.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

Baraka's Totem Press: published early works by Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and other Beat and Downtown experimental writers.

- ^ Harrison, K. C. (2014). "LeRoi Jones's Radio and the Literary "Break" from Ellison to Burroughs". African American Review. 47 (2/3): 357–74. doi:10.1353/afa.2014.0042. JSTOR 24589759. S2CID 160151597.

- ^ Bill Morgan: The Letters of Allen Ginsberg. Video at fora.tv. October 23, 2008.

- ^ PERLOFF, MARJORIE (2013). "Allen Ginsberg". Poetry. 202 (4): 351–53. JSTOR 23561794.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ginsberg, Allen (April 3, 2015). "The Vomit of a Mad Tyger". Lion's Roar. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ Prideaux, Ed (December 3, 2019). "The true story of Hare Krishna: Sex, drugs, The Beatles and 50 years of scandal". The Independent. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ Fields, Rick (1992). How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America. Shambhala Publications. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-87773-631-8.

- ^ Wills, D. (2007). Wills, D. (ed.). "Buddhism and the Beats". Beatdom. Vol. 1. Dundee: Mauling Press. pp. 9–13. Archived from the original on May 1, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Brooks 1992, pp. 78–79

- ^ Szatmary 1996, p. 149

- ^ Ginsberg & Morgan 1986, p. 36

- ^ Muster 1997, p. 25

- ^ Bromley & Shinn 1989, p. 106

- ^ Chryssides & Wilkins 2006, p. 213

- ^ Joplin, Laura (1992). Love, Janis. New York: Villard Books. p. 182. ISBN 0-679-41605-6.

- ^ Chowka, Peter Barry, "This is Allen Ginsberg? Archived April 8, 2019, at the Wayback Machine" (Interview), New Age Journal, April 1976. "I had known Swami Bhaktivedanta and was somewhat guided by him [...] spiritual friend. I practiced the Hare Krishna chant, practiced it with him, sometimes in mass auditoriums and parks in the Lower East Side of New York. Actually, I'd been chanting it since '63, after coming back from India. I began chanting it, in Vancouver at a great poetry conference, for the first time in '63, with Duncan and Olson and everybody around, and then continued. When Bhaktivedanta arrived on the Lower East Side in '66 it was reinforcement for me, like 'the reinforcements had arrived' from India."

- ^ Klausner, Linda T. (April 22, 2011), "American Beat Yogi: An Exploration of the Hindu and Indian Cultural Themes in Allen Ginsberg", Masters Thesis: Literature, Culture, and MediaLund University.

- ^ Konigsberg, Eric (February 29, 2008), "Buckley's Urbane Debating Club: Firing Line Set a Standard For Political Discourse on TV", The New York Times, Metro Section, p. B1.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 468

- ^ Mitra, Alo (May 9, 2008), Hungryalist Influence on Allen Ginsberg . thewastepaper.blogspot.com.

- ^ Kramer, Jane (1968), Allen Ginsberg in America. New York: Random House, p. xvii.

- ^ "Transforming Minds: Kyabje Gelek Rimnpohce and Friends". jewelheart.org. Jewel Heart. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Spiegel, Alison (September 29, 2021). "Inside the New Allen Ginsberg Photography Exhibit at Tibet House US". Tricycle Magazine. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Paljor Chatag, Ben (2022). "Curatorial Reflections on 'Transforming Minds: Kyabje Gelek Rimpoche and Friends, Photographs by Allen Ginsberg 1989–1997'". Yeshe, A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities. 2 (1). Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 312

- ^ Morgan 2007

- ^ a b "Silence = Death". Teddy Award.

- ^ Rhoades, Lindsey (March 8, 2017). "Echo in Eternity: The Indelible Mark of Arthur Russell". Stereogum.

- ^ "Arthur Russell / Allen Ginsberg Track Discovered". September 13, 2010.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 649

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen Collected Poems 1947–1997, pp. 1160–61.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 651

- ^ Strauss, Robert (March 28, 2004). "Sometimes the Grave Is a Fine and Public Place". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ^ Smith, Dinitia (May 16, 1998). "Chanting in Homage to Allen Ginsberg". The New York Times. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

- ^ "Allen Ginsberg Planet News Memorial at St John the Divine, New York City, May 14, 1998 Part 1". allenginsbergofficial. Retrieved July 19, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Allen Ginsberg Planet News Memorial at St John the Divine, New York City, May 14, 1998 Part 2". allenginsbergofficial. Retrieved July 19, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ Michalis Limnios (March 1, 2013). "Poet and author Catfish McDaris says stories from his experiences from the poetry and music world". Blues.gr.

- ^ Clarke, Roger (March 3, 1998). "Roger Clarke | Gus Van Sant". London Evening Standard. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Morgan, Bill (ed.) (2006), "Howl" on Trial: The Battle for Free Expression. California: City of Lights.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ginsberg, Allen. Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays 1952–1995. Harper Perennial, 2001. ISBN 0-06-093081-0

- ^ Barsky, Robert F. (1998), "Marching with the Armies of the Night" Archived January 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine in Noam Chomsky: a life of dissent. 1st ed. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press

- ^ Mitford, Jessica (1969) The Trial of Dr. Spock, the Rev. William Sloane Coffin Jr., Michael Ferber, Mitchell Goodman, and Marcus Raskin [1st ed.]. New York: Knopf, p. 255.

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest", New York Post. January 30, 1968.

- ^ "A Call to War Tax Resistance", The Cycle, May 14, 1970, p. 7.

- ^ Purdham, Todd (August 14, 1988), "Melee in Tompkins Sq. Park: Violence and Its Provocation". The New York Times, sect. 1, part 1, p. 1, col. 4: Metropolitan Desk.

- ^ Schumacher, Michael, ed. (2002). Family Business: Selected Letters Between a Father and Son. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58234-216-0.

- ^ "Allen Ginsberg (8/11/96)". Gwu.edu. April 26, 1965. Archived from the original on November 9, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ Rojas, Rafael (2016). Fighting Over Fidel The New York Intellectuals and the Cuban Revolution. Duke University Press. p. 199.

- ^ Raskin 2004, p. 170

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (2008), The Letters of Allen Ginsberg. Philadelphia, Da Capo Press, p. 359. For context, see also Morgan 2007, pp. 474–75.

- ^ a b Allen Ginsberg's Life Archived March 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. illinois.edu

- ^ Ginsberg, Allan (2001), Selected Poems 1947–1995, "Kral Majales", Harper Collins Publishers, p. 147.

- ^ Yanosik, Joseph (March 1996), The Plastic People of the Universe. furious.com.

- ^ Vodrážka, Karel; Andrew Lass (1998). "Final Report on the Activities of the American Poet Allen Ginsberg and His Deportation from Czechoslovakia". The Massachusetts Review. 39 (2): 187–96.

- ^ a b c d e f g David Carter, ed. (2002). Spontaneous Mind: Selected Interviews 1958–1996. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-093082-0.

- ^ "LGBT History: Not Just West Village Bars". gvshp.org. January 9, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Andrea (2002). "Allen Ginsberg's advocacy of pedophilia debated in community". Intermountain Jewish News.

- ^ O'Donnell, Ian; Milner, Claire (2012). Child Pornography: Crime, Computers and Society. Routledge. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-135-84635-0. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Thrift, Matt (January 22, 2020). "Pedophiles on display". My TJ Now.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (1977). Mind Breaths. San Francisco, California: City Lights Publisher. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-313-29389-9.

- ^ Echols, Mike (1996). Brother Tony's Boys: The Largest Case of Child Prostitution in U.S. History. Amherst, New York: Prometheus. p. 324. ISBN 1-57392-051-7. Retrieved July 5, 2025.

- ^ Dworkin, Andrea (2002), Heartbreak: The Political Memoir of a Feminist Militant. New York: Basic Books, p. 43.

- ^ Miller, Laura (March 10, 2002). "Antiporn Star". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ "Ginsberg and Me". www.advocate.com. October 28, 2010. Archived from the original on July 26, 2024. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Fisher, Marc (February 22, 2014). "Marijuana's rising acceptance comes after many failures. Is it now legalization's time?". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ Palmer, Alex (2010). Literary Miscellany: Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Literature. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-61608-095-2.

- ^ a b c Hendryckx, Michiel (June 21, 2018). "When Allen Ginsberg met the head of the CIA – and offered him a wager". The conversation. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Heroin, U.S. tie probed". Boca Raton News. Vol. 17, no. 218. Boca Raton, Florida. United Press International. October 1, 1972. p. 9B. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen, and Hyde, Lewis. On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1984. Print.

- ^ Morgan 2007, pp. 470–77

- ^ "Heroin Charges Aired". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Vol. XLVII, no. 131. Daytona Beach Florida. Associated Press. June 3, 1972. p. 6. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (April 26, 1976). Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. Report – 94th Congress, 2d session, Senate ; no. 94-755. Vol. Book 1. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 227–28. hdl:2027/mdp.39015070725273.

- ^ United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs (January 11, 1973). The U.S. Heroin Problem and Southeast Asia: Report of a Staff Survey Team of the Committee of Foreign Affairs. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 10, 30, 61. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities 1976, pp. 205, 227.

- ^ "Allen Ginsberg, Master Poet of Beat Generation, Dies at 70". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Lawlor, William. Beat culture : lifestyles, icons, and impact. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2005. Print.

- ^ Kramer, Jane (August 10, 1968). "The Father of Flower Power". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (1995). Howl: Original Draft Facsimile, Transcript & Variant Versions, Fully Annotated by Author, with Contemporaneous Correspondence, Account of First Public Reading, Legal Skirmishes, Precursor Texts & Bibliography. Barry Miles (Ed.). Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-092611-2. pp. 131, 132, 139–140.

- ^ Cornell, Tom. "Catholic Worker Pacifism: An Eyewitness to History". Catholic Worker Homepage. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ "A lot of nerve". The Guardian. London. December 30, 1999. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ "The Ten Most Incomprehensible Bob Dylan Interviews of All Time – Vulture". New York. October 4, 2007. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ Plotz, David (March 8, 1998). "Bob Dylan – By David Plotz – Slate Magazine". Slate. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ O'Hagan, Sean (March 25, 2001). "Well, how does it feel?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ "First Blues: Rags, Ballads and Harmonium Songs | Smithsonian Folkways". Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Patti (2010). Just Kids. New York: Ecco. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-06-093622-8.

- ^ Wills, D., "Allen Ginsberg and Bob Dylan", Beatdom No. 1 (2007).

- ^ "Birdbrain!". The Allen Ginsberg Project. December 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ "Ballad of the Skeletons – Allen Ginsberg – Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic.

- ^ Gorski, Hedwig (Spring 2008). "Interview with Robert Creeley" (PDF). Journal of American Studies of Turkey (27): 73–81. ISSN 1300-6606. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ Jackson, Brian (2010). "Modernist Looking: Surreal Impressions in the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 52 (3): 298–323. doi:10.1353/tsl.2010.0003. S2CID 162063608. ProQuest 751273038.

- ^ Hyde, Lewis, ed. (1984). On the poetry of Allen Ginsberg. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-472-09353-3. OCLC 10878519.