Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cardamine

View on Wikipedia

| Cardamine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cardamine oligosperma | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Brassicales |

| Family: | Brassicaceae |

| Tribe: | Cardamineae |

| Genus: | Cardamine L. |

| Species | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

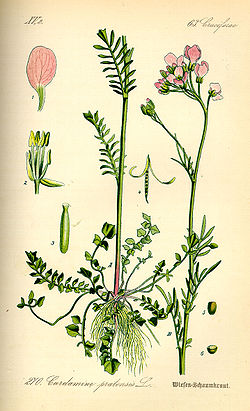

Cardamine is a large genus of flowering plants in the mustard family, Brassicaceae, known as bittercresses and toothworts. It contains more than 200 species of annuals and perennials.[1] Species in this genus can be found in diverse habitats worldwide, except the Antarctic.[1] The name Cardamine is derived from the Greek kardaminē, water cress, from kardamon, pepper grass.[2]

Description

[edit]The leaves can have different forms, from minute to medium in size. They can be simple, pinnate or bipinnate. They are basal and cauline (growing on the upper part of the stem), with narrow tips. They are rosulate (forming a rosette). The blade margins can be entire, serrate or dentate. The stem internodes lack firmness.[clarification needed]

The radially symmetrical flowers grow in a racemose many-flowered inflorescence or in corymbs. The white, pink or purple flowers are minute to medium-sized. The petals are longer than the sepals. The fertile flowers are hermaphroditic.[citation needed]

Taxonomy

[edit]The genus Cardamine was first formally named in 1753 by Carl Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum.[3] As of August 2024[update], there are 264 accepted species in Kew's Plants of the World Online database.[1]

The genus name Dentaria is a commonly used synonym for some species of Cardamine.

Species

[edit]Select species include:[1]

- Cardamine amara L. – large bittercress

- Cardamine angulata Hook. – seaside bittercress, angled bittercress

- Cardamine angustata O.E.Schulz – slender toothwort

- Cardamine bellidifolia L. – alpine bittercress, alpine cress

- Cardamine bilobata Kirk

- Cardamine breweri S.Watson – Brewer's bittercress

- Cardamine bulbifera (L.) Crantz – coralroot

- Cardamine bulbosa (Schreb. ex Muhl.) Britton, Sterns & Poggenb. – bulbous bittercress, spring cress

- Cardamine caldeirarum Guthnick ex Seub. – Azorean bittercress

- Cardamine californica (Nutt.) Greene – milkmaids

- Cardamine clematitis Shuttlew. ex S.Watson – small mountain bittercress

- Cardamine concatenata (Michx.) O.Schwarz – cutleaf toothwort, cut-leaved toothwort

- Cardamine constancei Detling – Constance's bittercress

- Cardamine cordifolia A.Gray – heartleaf bittercress, large Mountain bittercress

- Cardamine corymbosa Hook.f. – New Zealand bittercress

- Cardamine debilis DC. – roadside bittercress

- Cardamine diphylla (Michx.) Alph.Wood – crinkleroot, twin-leaved toothwort

- Cardamine dissecta (Leavenw.) Al-Shehbaz – forkleaf toothwort

- Cardamine douglassii Britton – limestone bittercress

- Cardamine enneaphyllos (L.) Crantz – drooping bittercress

- Cardamine fargesiana Al-Shehbaz

- Cardamine flagellifera O.E.Schulz – Blue Ridge bittercress

- Cardamine flexuosa With. – woodland bittercress, wavy bittercress

- Cardamine glacialis (G.Forst.) DC.

- Cardamine gouldii Al-Shehbaz

- Cardamine gunnii Hewson

- Cardamine heptaphylla (Vill.) O.E.Schulz – pinnate coralroot

- Cardamine hirsuta L. – hairy bittercress

- Cardamine impatiens L. – narrowleaf bittercress

- Cardamine jamesonii Hook.

- Cardamine leucantha (Tausch) O.E.Schulz – Korean bittercress[4]

- Cardamine longii Fernald – Long's bittercress

- Cardamine lyrata Bunge

- Cardamine macrocarpa Brandegee – largeseed bittercress

- Cardamine maxima (Nutt.) Alph.Wood – large toothwort

- Cardamine micranthera Rollins – small-anthered bittercress, streambank bittercress

- Cardamine microphylla Adams – small-leaf bittercress

- Cardamine nuttallii Greene – Nuttall's toothwort

- Cardamine nymanii Gand. – lady's smock

- Cardamine occidentalis (S.Watson ex B.L.Rob.) Howell – big western bittercress

- Cardamine oligosperma Nutt. – Idaho bittercress, little western bittercress

- Cardamine pachystigma (S.Watson) Rollins – serpentine bittercress

- Cardamine parviflora L. – sand bittercress, small-flowered bittercress

- Cardamine pattersonii L.F.Hend. – Saddle Mountain bittercress

- Cardamine penduliflora O.E.Schulz – Willamette Valley bittercress

- Cardamine pensylvanica Muhl. ex Willd. – Pennsylvania bittercress, Quaker bittercress

- Cardamine pentaphyllos (L.) Crantz

- Cardamine pratensis L. – cuckoo flower, lady's smock, meadow cress

- Cardamine purpurascens (O.E.Schulz) Al-Shehbaz & al.

- Cardamine purpurea Cham. & Schltdl. – purple bittercress

- Cardamine raphanifolia Pourr. – greater cuckooflower

- Cardamine rotundifolia Michx. – American bittercress, mountain watercress

- Cardamine rupicola (O.E.Schulz) C.L.Hitchc. – cliff bittercress

- Cardamine trifolia L. – trefoil cress

- Cardamine uliginosa M.Bieb.

-

Cardamine concatenata

cutleaf toothwort -

Cardamine nuttallii

Nuttall's toothwort -

Cardamine pattersonii

Saddle Mountain bittercress -

Cardamine trifolia

trefoil bittercress

Ecology

[edit]

Certain members of the genus, particularly Cardamine diphylla and Cardamine angustata, and to a lesser extent Cardamine concatenata, are also used as one of the main food sources for the butterfly Pieris oleracea.[5][page needed]

Uses

[edit]The roots of most species are edible raw.[6]

Some species were reputed to have medicinal qualities (treatment of heart or stomach ailments).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Cardamine L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Definition of CARDAMINE". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ "Cardamine L." ipni.org. International Plant Names Index. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ English Names for Korean Native Plants (PDF). Pocheon: Korea National Arboretum. 2015. p. 387. ISBN 978-89-97450-98-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2016 – via Korea Forest Service.

- ^ Davis, Samantha L. (17 May 2015). Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis (PDF) (PhD thesis). Wright State University. pp. 24, 27, 43. S2CID 89373310. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ Angier, Bradford (1974). Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 226. ISBN 0-8117-0616-8. OCLC 799792.

Bibliography

[edit]- Al-Shehbaz, Ilsan A.; Marhold, Karol; Lihová, Judita (2020-07-30). "Cardamine". Flora of North America. p. 464.

- Taxonomic Revision of Cardamine

- Lihová, J.; Marhold, K. (2003). "Taxonomy and distribution of the Cardamine pratensis group (Brassicaceae) in Slovenia". Phyton (Horn). 43: 241–261.

- Lihová, J.; Marhold, K.; Neuffer, B. (2000). "Taxonomy of Cardamine amara in the Iberian Peninsula". Taxon. 49 (4): 747–763. doi:10.2307/1223975. JSTOR 1223975. S2CID 85625889.

- Sun, Jianqiang; Shimizu-Inatsugi, Rie; Hofhuis, Hugo; Shimizu, Kentaro; Hay, Angela; Shimizu, Kentaro K.; Sese, Jun (2020). "A recently formed triploid Cardamine insueta inherits leaf vivipary and submergence tolerance traits of parents". Front. Genet. 11 567262. doi:10.3389/fgene.2020.567262. PMC 7573311. PMID 33133153. S2CID 222135582.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cardamine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cardamine at Wikimedia Commons