Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Plant stem

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

A stem is one of two main structural axes of a vascular plant, the other being the root. It supports leaves, flowers and fruits, transports water and dissolved substances between the roots and the shoots in the xylem and phloem, engages in photosynthesis, stores nutrients, and produces new living tissue.[1] The stem can also be called the culm, halm, haulm, stalk, or thyrsus.

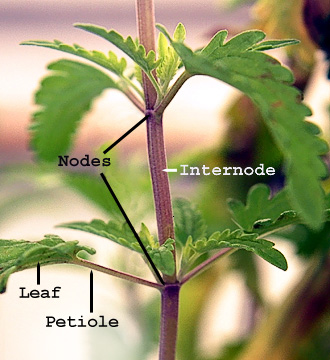

The stem is normally divided into nodes and internodes:[2]

- The nodes are the points of attachment for leaves and can hold one or more leaves. There are sometimes axillary buds between the stem and leaf which can grow into branches (with leaves, conifer cones, or flowers).[2] Adventitious roots (e.g. brace roots) may also be produced from the nodes. Vines may produce tendrils from nodes.

- The internodes distance one node from another.[2]

The term "shoots" is often confused with "stems"; "shoots" generally refers to new fresh plant growth, including both stems and other structures like leaves or flowers.[2]

In most plants, stems are located above the soil surface, but some plants have underground stems.

Stems have several main functions:[3]

- Support for and the elevation of leaves, flowers, and fruits. The stems keep the leaves in the light and provide a place for the plant to keep its flowers and fruits.

- Transport of fluids between the roots and the shoots in the xylem and phloem.

- Storage of nutrients.

- Production of new living tissue. The normal lifespan of plant cells is one to three years. Stems have cells called meristems that annually generate new living tissue.

- Photosynthesis.

Stems have two pipe-like tissues called xylem and phloem. The xylem tissue arises from the cell facing inside and transports water by the action of transpiration pull, capillary action, and root pressure. The phloem tissue arises from the cell facing outside and consists of sieve tubes and their companion cells. The function of phloem tissue is to distribute food from photosynthetic tissue to other tissues. The two tissues are separated by cambium, a tissue that divides to form xylem or phloem cells.

Specialized terms

[edit]

Stems are often specialized for storage, asexual reproduction, protection, or photosynthesis, including the following:

- Acaulescent: Used to describe stems in plants that appear to be stemless. Actually these stems are just extremely short, the leaves appearing to rise directly out of the ground, e.g. some Viola species.

- Arborescent: Tree with woody stems normally with a single trunk.

- Axillary bud: A bud which grows at the point of attachment of an older leaf with the stem. It potentially gives rise to a shoot.

- Branched: Aerial stems are described as being branched or unbranched.

- Bud: An embryonic shoot with immature stem tip.

- Bulb: A short vertical underground stem with fleshy storage leaves attached, e.g. onion, daffodil, and tulip. Bulbs often function in reproduction by splitting to form new bulbs or producing small new bulbs termed bulblets. Bulbs are a combination of stem and leaves so may better be considered as leaves because the leaves make up the greater part.

- Caespitose: When stems grow in a tangled mass or clump or in low growing mats.

- Cladode (including phylloclade): A flattened stem that appears leaf-like and is specialized for photosynthesis,[4] e.g. cactus pads.

- Climbing: Stems that cling or wrap around other plants or structures.

- Corm: A short enlarged underground storage stem, e.g. taro, crocus, gladiolus.

- Decumbent: A stem that lies flat on the ground and turns upwards at the ends.

- Fruticose: Stems that grow shrublike with woody like habit.

- Herbaceous: Non woody stems which die at the end of the growing season.

- Internode: An interval between two successive nodes. It possesses the ability to elongate, either from its base or from its extremity depending on the species.

- Node: A point of attachment of a leaf or a twig on the stem in seed plants. A node is a very small growth zone.

- Pedicel: Stems that serve as the stalk of an individual flower in an inflorescence or infrutescence.

- Peduncle: A stem that supports an inflorescence or a solitary flower.

- Prickle: A sharpened extension of the stem's outer layers, e.g. rose thorns.

- Pseudostem: A false stem made of the rolled bases of leaves, which may be 2 to 3 m (6 ft 7 in to 9 ft 10 in) tall, as in banana.

- Rhizome: A horizontal underground stem that functions mainly in reproduction but also in storage, e.g. most ferns, iris.

- Runner: A type of stolon, horizontally growing on top of the ground and rooting at the nodes, aids in reproduction. e.g. garden strawberry, Chlorophytum comosum.

- Scape: A stem that holds flowers that comes out of the ground and has no normal leaves. Hosta, lily, iris, garlic.

- Stolon: A horizontal stem that produces rooted plantlets at its nodes and ends, forming near the surface of the ground.

- Thorn: A modified stem with a sharpened point.

- Tuber: A swollen, underground storage stem adapted for storage and reproduction, e.g. potato.

- Woody: Hard textured stems with secondary xylem.

- Sapwood: A woody stem, the layer of secondary phloem that surrounds the heartwood; usually active in fluid transport

Stem structure

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2025) |

Stem usually consist of three tissues: dermal tissue, ground tissue, and vascular tissue.[5]

Dermal tissue covers the outer surface of the stem and usually functions to protect the stem tissue, and control gas exchange. The predominant cells of dermal tissue are epidermal cells.[6]

Ground tissue usually consists mainly of parenchyma, collenchyma and sclerenchyma cells, and they surround vascular tissue. Ground tissue is important in aiding metabolic activities (eg. respiration, photosynthesis, transport, storage) as well as acting as structural support and forming new meristems.[7] Most or all ground tissue may be lost in woody stems.

Vascular tissue, consisting of xylem, phloem and cambium; provides long distance transport of water, minerals and metabolites (sugars, amino acids); whilst aiding structural support and growth. The arrangement of the vascular tissues varies widely among plant species.[8]

Dicot stems

[edit]Dicot stems with primary growth have pith in the center, with vascular bundles forming a distinct ring visible when the stem is viewed in cross section. The outside of the stem is covered with an epidermis, which is covered by a waterproof cuticle. The epidermis also may contain stomata for gas exchange and multicellular stem hairs called trichomes. A cortex consisting of hypodermis (collenchyma cells) and endodermis (starch containing cells) is present above the pericycle and vascular bundles.

Woody dicots and many nonwoody dicots have secondary growth originating from their lateral or secondary meristems: the vascular cambium and the cork cambium or phellogen. The vascular cambium forms between the xylem and phloem in the vascular bundles and connects to form a continuous cylinder. The vascular cambium cells divide to produce secondary xylem to the inside and secondary phloem to the outside. As the stem increases in diameter due to production of secondary xylem and secondary phloem, the cortex and epidermis are eventually destroyed. Before the cortex is destroyed, a cork cambium develops there. The cork cambium divides to produce waterproof cork cells externally and sometimes phelloderm cells internally. Those three tissues form the periderm, which replaces the epidermis in function. Areas of loosely packed cells in the periderm that function in gas exchange are called lenticels.

Secondary xylem is commercially important as wood. The seasonal variation in growth from the vascular cambium is what creates yearly tree rings in temperate climates. Tree rings are the basis of dendrochronology, which dates wooden objects and associated artifacts. Dendroclimatology is the use of tree rings as a record of past climates. The aerial stem of an adult tree is called a trunk. The dead, usually darker inner wood of a large diameter trunk is termed the heartwood and is the result of tylosis. The outer, living wood is termed the sapwood.

Monocot stems

[edit]Vascular bundles are present throughout the monocot stem, although concentrated towards the outside. This differs from the dicot stem that has a ring of vascular bundles and often none in the center. The shoot apex in monocot stems is more elongated. Leaf sheathes grow up around it, protecting it. This is true to some extent of almost all monocots. Monocots rarely produce secondary growth and are therefore seldom woody, with palms and bamboo being notable exceptions. However, many monocot stems increase in diameter via anomalous secondary growth.

Gymnosperm stems

[edit]

All gymnosperms are woody plants. Their stems are similar in structure to woody dicots except that most gymnosperms produce only tracheids in their xylem, not the vessels found in dicots. Gymnosperm wood also often contains resin ducts. Woody dicots are called hardwoods, e.g. oak, maple and walnut. In contrast, softwoods are gymnosperms, such as pine, spruce and fir.

Fern stems

[edit]

Most ferns have rhizomes with no vertical stem. The exception is tree ferns, which have vertical stems that can grow up to about 20 metres. The stem anatomy of ferns is more complicated than that of dicots because fern stems often have one or more leaf gaps in cross section. A leaf gap is where the vascular tissue branches off to a frond. In cross section, the vascular tissue does not form a complete cylinder where a leaf gap occurs. Fern stems may have solenosteles or dictyosteles or variations of them. Many fern stems have phloem tissue on both sides of the xylem in cross-section.

Relation to xenobiotics

[edit]Foreign chemicals such as air pollutants,[9] herbicides and pesticides can damage stem structures.

Economic importance

[edit]

There are thousands of species whose stems have economic uses. Stems provide a few major staple crops such as potato and taro. Sugarcane stems are a major source of sugar. Maple sugar is obtained from trunks of maple trees. Vegetables from stems are asparagus, bamboo shoots, cactus pads or nopalitos, kohlrabi, and water chestnut. The spice, cinnamon is bark from a tree trunk. Gum arabic is an important food additive obtained from the trunks of Acacia senegal trees. Chicle, the main ingredient in chewing gum, is obtained from trunks of the chicle tree.

Medicines obtained from stems include quinine from the bark of cinchona trees, camphor distilled from wood of a tree in the same genus that provides cinnamon, and the muscle relaxant curare from the bark of tropical vines.

Wood is used in thousands of ways; it can be used to create buildings, furniture, boats, airplanes, wagons, car parts, musical instruments, sports equipment, railroad ties, utility poles, fence posts, pilings, toothpicks, matches, plywood, coffins, shingles, barrel staves, toys, tool handles, picture frames, veneer, charcoal and firewood. Wood pulp is widely used to make paper, paperboard, cellulose sponges, cellophane and some important plastics and textiles, such as cellulose acetate and rayon. Bamboo stems also have hundreds of uses, including in paper, buildings, furniture, boats, musical instruments, fishing poles, water pipes, plant stakes, and scaffolding. Trunks of palms and tree ferns are often used for building. Stems of reed are an important building material for use in thatching in some areas.

Tannins used for tanning leather are obtained from the wood of certain trees, such as quebracho. Cork is obtained from the bark of the cork oak. Rubber is obtained from the trunks of Hevea brasiliensis. Rattan, used for furniture and baskets, is made from the stems of tropical vining palms. Bast fibers for textiles and rope are obtained from stems of plants like flax, hemp, jute and ramie. The earliest known paper was obtained from the stems of papyrus by the ancient Egyptians.

Amber is fossilized sap from tree trunks; it is used for jewelry and may contain preserved animals. Resins from conifer wood are used to produce turpentine and rosin. Tree bark is often used as a mulch and in growing media for container plants. It also can become the natural habitat of lichens.

Some ornamental plants are grown mainly for their attractive stems, e.g.:

- White bark of paper birch

- Twisted branches of corkscrew willow and Harry Lauder's walking stick (Corylus avellana 'Contorta')

- Red, peeling bark of paperbark maple

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Plant Stems: Physiology and Functional Morphology. Elsevier. 1995-07-19. ISBN 978-0-08-053908-9.

- ^ a b c d Britannica Lessons Class VI Science The Living World. Popular Prakashan. 2002. ISBN 9788171549719.

- ^ Raven, Peter H., Ray Franklin Evert, and Helena Curtis (1981). Biology of Plants. New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 0-87901-132-7.

- ^ Goebel, K.E.v. (1969) [1905]. Organography of plants, especially of the Archegoniatae and Spermaphyta. New York: Hofner publishing company.

- ^ "Stem Anatomy". LibreTexts Biology. 11 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Stems - Stem Anatomy". LibreTexts Biology. 11 June 2024. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Simpson, Michael G. (2019). Plant Systematics (3rd ed.). New York City, USA: Elsevier. pp. 537–566. ISBN 978-0-12-812628-8.

- ^ Lopez, F. B.; Barclay, G. F. (2017). Pharmacognosy: Fundamentals, Applications and Strategies. University of the West Indies: Elsevier. pp. 45–60. ISBN 978-0-12-802104-0.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2010. "Abiotic factor". Encyclopedia of Earth. Emily Monosson and C. Cleveland, eds. National Council for Science and the Environment Archived 2013-06-08 at the Wayback Machine. Washington, D.C.

Further reading

[edit]- Speck, T.; Burgert, I. (2011). "Plant Stems: Functional Design and Mechanics". Annual Review of Materials Research. 41: 169–193. Bibcode:2011AnRMS..41..169S. doi:10.1146/annurev-matsci-062910-100425.

External links

[edit] Media related to Plant stems at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Plant stems at Wikimedia Commons- Overview of stem anatomy