Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Transverse mode

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

A transverse mode of electromagnetic radiation is a particular electromagnetic field pattern of the radiation in the plane perpendicular (i.e., transverse) to the radiation's propagation direction. Transverse modes occur in radio waves and microwaves confined to a waveguide, and also in light waves in an optical fiber and in a laser's optical resonator.[1]

Transverse modes occur because of boundary conditions imposed on the wave by the waveguide. For example, a radio wave in a hollow metal waveguide must have zero tangential electric field amplitude at the walls of the waveguide, so the transverse pattern of the electric field of waves is restricted to those that fit between the walls. For this reason, the modes supported by a waveguide are quantized. The allowed modes can be found by solving Maxwell's equations for the boundary conditions of a given waveguide.

Types of modes

[edit]Unguided electromagnetic waves in free space, or in a bulk isotropic dielectric, can be described as a superposition of plane waves; these can be described as TEM modes as defined below.

However in any sort of waveguide where boundary conditions are imposed by a physical structure, a wave of a particular frequency can be described in terms of a transverse mode (or superposition of such modes). These modes generally follow different propagation constants. When two or more modes have an identical propagation constant along the waveguide, then there is more than one modal decomposition possible in order to describe a wave with that propagation constant (for instance, a non-central Gaussian laser mode can be equivalently described as a superposition of Hermite-Gaussian modes or Laguerre-Gaussian modes which are described below).

Waveguides

[edit]

Modes in waveguides can be classified as follows:

- Transverse electromagnetic (TEM) modes

- Neither electric nor magnetic field in the direction of propagation.

- Transverse electric (TE) modes

- No electric field in the direction of propagation. These are sometimes called H modes because there is only a magnetic field along the direction of propagation (H is the conventional symbol for magnetic field).

- Transverse magnetic (TM) modes

- No magnetic field in the direction of propagation. These are sometimes called E modes because there is only an electric field along the direction of propagation.

- Hybrid modes

- Non-zero electric and magnetic fields in the direction of propagation. See also Planar transmission line § Modes.

Conductor-based transmission lines

[edit]In coaxial cable energy is normally transported in the fundamental TEM mode. The TEM mode is also usually assumed for most other electrical conductor line formats as well. This is mostly an accurate assumption, but a major exception is microstrip which has a significant longitudinal component to the propagated wave due to the inhomogeneity at the boundary of the dielectric substrate below the conductor and the air above it. Inhomogeneity also occurs at connectors or bends in a coaxial cable. Non-TEM modes created by connectors are usually negligible unless the signal has a high enough frequency. This is referred to as maximum extraneous-mode-free operation[2] or simply mode-free operation[3][4] frequency of the connector.

In an optical fiber or other dielectric waveguide, modes are generally of the hybrid type.

Waveguides

[edit]Hollow metallic waveguides filled with a homogeneous, isotropic material (usually air) support TE and TM modes but not the TEM mode. In rectangular waveguides, rectangular mode numbers are designated by two suffix numbers attached to the mode type, such as TEmn or TMmn, where m is the number of half-wave patterns across the width of the waveguide and n is the number of half-wave patterns across the height of the waveguide. In circular waveguides, circular modes exist and here m is the number of full-wave patterns along the circumference and n is the number of half-wave patterns along the diameter.[5][6]

Optical fibers

[edit]The number of modes in an optical fiber distinguishes multi-mode optical fiber from single-mode optical fiber. To determine the number of modes in a step-index fiber, the V number needs to be determined: where is the wavenumber, is the fiber's core radius, and and are the refractive indices of the core and cladding, respectively. Fiber with a V-parameter of less than 2.405 only supports the fundamental mode (a hybrid mode), and is therefore a single-mode fiber whereas fiber with a higher V-parameter has multiple modes.[7]

Decomposition of field distributions into modes is useful because a large number of field amplitudes readings can be simplified into a much smaller number of mode amplitudes. Because these modes change over time according to a simple set of rules, it is also possible to anticipate future behavior of the field distribution. These simplifications of complex field distributions ease the signal processing requirements of fiber-optic communication systems.[8]

The modes in typical low refractive index contrast fibers are usually referred to as LP (linear polarization) modes, which refers to a scalar approximation for the field solution, treating it as if it contains only one transverse field component.[9]

Lasers

[edit]

In a laser with cylindrical symmetry, the transverse mode patterns are described by a combination of a Gaussian beam profile with a Laguerre polynomial. The modes are denoted TEMpl where p and l are integers labeling the radial and angular mode orders, respectively. The intensity at a point (r,φ) (in polar coordinates) from the centre of the mode is given by:

where ρ = 2r2/w2, Ll

p is the associated Laguerre polynomial of order p and index l, and w is the spot size of the mode corresponding to the Gaussian beam radius.

With p = l = 0, the TEM00 mode is the lowest order. It is the fundamental transverse mode of the laser resonator and has the same form as a Gaussian beam. The pattern has a single lobe, and has a constant phase across the mode. Modes with increasing p show concentric rings of intensity, and modes with increasing l show angularly distributed lobes. In general there are 2l(p+1) spots in the mode pattern (except for l = 0). The TEM0i* mode, the so-called doughnut mode, is a special case consisting of a superposition of two TEM0i modes (i = 1, 2, 3), rotated 360°/4i with respect to one another.

The overall size of the mode is determined by the Gaussian beam radius w, and this may increase or decrease with the propagation of the beam, however the modes preserve their general shape during propagation. Higher order modes are relatively larger compared to the TEM00 mode, and thus the fundamental Gaussian mode of a laser may be selected by placing an appropriately sized aperture in the laser cavity.

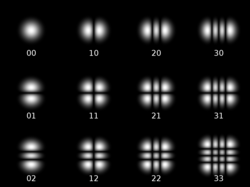

In many lasers, the symmetry of the optical resonator is restricted by polarizing elements such as Brewster's angle windows. In these lasers, transverse modes with rectangular symmetry are formed. These modes are designated TEMmn with m and n being the horizontal and vertical orders of the pattern. The electric field pattern at a point (x,y,z) for a beam propagating along the z-axis is given by[10] where , , , and are the waist, spot size, radius of curvature, and Gouy phase shift as given for a Gaussian beam; is a normalization constant; and is the k-th physicist's Hermite polynomial. The corresponding intensity pattern is

The TEM00 mode corresponds to exactly the same fundamental mode as in the cylindrical geometry. Modes with increasing m and n show lobes appearing in the horizontal and vertical directions, with in general (m + 1)(n + 1) lobes present in the pattern. As before, higher-order modes have a larger spatial extent than the 00 mode.

The phase of each lobe of a TEMmn is offset by π radians with respect to its horizontal or vertical neighbours. This is equivalent to the polarization of each lobe being flipped in direction.

The overall intensity profile of a laser's output may be made up from the superposition of any of the allowed transverse modes of the laser's cavity, though often it is desirable to operate only on the fundamental mode.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Transverse electromagnetic mode"

- ^ Eisenhart, R. L. (1998). "A novel wideband TM01-to-TE11 mode converter". 998 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest (Cat. No.98CH36192). q: 249–252.

- ^ Hannon, Michael J.; Malloy, Pat. "Application Guide to RF Coaxial Connectors and Cables" (PDF). Retrieved 26 February 2025.

- ^ hobbs (14 July 2021). "What does "mode-free" mean, in the context of coaxial connectors?". Electrical Engineering Stack Exchange. Retrieved 26 February 2025.

- ^ F. R. Connor, Wave Transmission, pp.52-53, London: Edward Arnold 1971 ISBN 0-7131-3278-7.

- ^ U.S. Navy-Marine Corps Military Auxiliary Radio System (MARS), NAVMARCORMARS Operator Course, Chapter 1, Waveguide Theory and Application, Figure 1-38.—Various modes of operation for rectangular and circular waveguides.

- ^ Kahn, Joseph M. (Sep 21, 2006). "Lecture 3: Wave Optics Description of Optical Fibers" (PDF). EE 247: Introduction to Optical Fiber Communications, Lecture Notes. Stanford University. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007. Retrieved 27 Jan 2015.

- ^ Paschotta, Rüdiger. "Modes". Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology. RP Photonics. Retrieved Jan 26, 2015.

- ^ K. Okamoto, Fundamentals of Optical Waveguides, pp. 71–79, Elsevier Academic Press, 2006, ISBN 0-12-525096-7.

- ^ Svelto, O. (2010). Principles of Lasers (5th ed.). p. 158.

![{\displaystyle I_{pl}(\rho ,\varphi )=I_{0}\rho ^{l}\left[L_{p}^{l}(\rho )\right]^{2}\cos ^{2}(l\varphi )e^{-\rho }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d604c8bbffd3ec4b4021204e96d6f8c7e318dd1d)

![{\displaystyle E_{mn}(x,y,z)=E_{0}{\frac {w_{0}}{w}}H_{m}\left({\frac {{\sqrt {2}}x}{w}}\right)H_{n}\left({\frac {{\sqrt {2}}y}{w}}\right)\exp \left[-(x^{2}+y^{2})\left({\frac {1}{w^{2}}}+{\frac {jk}{2R}}\right)-jkz-j(m+n+1)\zeta \right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c1f35547923fa54bfde2a6ea7ee108db48bf772)

![{\displaystyle I_{mn}(x,y,z)=I_{0}\left({\frac {w_{0}}{w}}\right)^{2}\left[H_{m}\left({\frac {{\sqrt {2}}x}{w}}\right)\exp \left({\frac {-x^{2}}{w^{2}}}\right)\right]^{2}\left[H_{n}\left({\frac {{\sqrt {2}}y}{w}}\right)\exp \left({\frac {-y^{2}}{w^{2}}}\right)\right]^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/67d351cea01bfe048709ffffdcdc5f615bae732c)