Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Magnetic field

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A magnetic field (sometimes called B-field[1]) is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents,[2]: ch1 [3] and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the magnetic field.[2]: ch13 [4]: 278 A permanent magnet's magnetic field pulls on ferromagnetic materials such as iron, and attracts or repels other magnets. In addition, a nonuniform magnetic field exerts minuscule forces on "nonmagnetic" materials by three other magnetic effects: paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and antiferromagnetism, although these forces are usually so small they can only be detected by laboratory equipment. Magnetic fields surround magnetized materials, electric currents, and electric fields varying in time. Since both strength and direction of a magnetic field may vary with location, it is described mathematically by a function assigning a vector to each point of space, called a vector field (more precisely, a pseudovector field).

In electromagnetics, the term magnetic field is used for two distinct but closely related vector fields denoted by the symbols B and H. In the International System of Units, the unit of B, magnetic flux density, is the tesla (in SI base units: kilogram per second squared per ampere),[5]: 21 which is equivalent to newton per meter per ampere. The unit of H, magnetic field strength, is ampere per meter (A/m).[5]: 22 B and H differ in how they take the medium and/or magnetization into account. In vacuum, the two fields are related through the vacuum permeability, ; in a magnetized material, the quantities on each side of this equation differ by the magnetization field of the material.

Magnetic fields are produced by moving electric charges and the intrinsic magnetic moments of elementary particles associated with a fundamental quantum property, their spin.[6][2]: ch1 Magnetic fields and electric fields are interrelated and are both components of the electromagnetic force, one of the four fundamental forces of nature.

Magnetic fields are used throughout modern technology, particularly in electrical engineering and electromechanics. Rotating magnetic fields are used in both electric motors and generators. The interaction of magnetic fields in electric devices such as transformers is conceptualized and investigated as magnetic circuits. Magnetic forces give information about the charge carriers in a material through the Hall effect. The Earth produces its own magnetic field, which shields the Earth's ozone layer from the solar wind and is important in navigation using a compass.

Description

[edit]The force on an electric charge depends on its location, speed, and direction; two vector fields are used to describe this force.[2]: ch1 The first is the electric field, which describes the force acting on a stationary charge and gives the component of the force that is independent of motion. The magnetic field, in contrast, describes the component of the force that is proportional to both the speed and direction of charged particles.[2]: ch13 The field is defined by the Lorentz force law and is, at each instant, perpendicular to both the motion of the charge and the force it experiences.

There are two different, but closely related vector fields which are both sometimes called the "magnetic field" written B and H.[note 1] While both the best names for these fields and exact interpretation of what these fields represent has been the subject of long running debate, there is wide agreement about how the underlying physics work.[7] Historically, the term "magnetic field" was reserved for H while using other terms for B, but many recent textbooks use the term "magnetic field" to describe B as well as or in place of H.[note 2] There are many alternative names for both (see sidebars).

The B-field

[edit]| Alternative names for B[8] |

|---|

The magnetic field vector B at any point can be defined as the vector that, when used in the Lorentz force law, correctly predicts the force on a charged particle at that point:[10][11]: 204

Here F is the force on the particle, q is the particle's electric charge, E is the external electric field, v, is the particle's velocity, and × denotes the cross product. The direction of force on the charge can be determined by a mnemonic known as the right-hand rule (see the figure).[note 3] Using the right hand, pointing the thumb in the direction of the current, and the fingers in the direction of the magnetic field, the resulting force on the charge points outwards from the palm. The force on a negatively charged particle is in the opposite direction. If both the speed and the charge are reversed then the direction of the force remains the same. For that reason a magnetic field measurement (by itself) cannot distinguish whether there is a positive charge moving to the right or a negative charge moving to the left. (Both of these cases produce the same current.) On the other hand, a magnetic field combined with an electric field can distinguish between these, see Hall effect below.

The first term in the Lorentz equation is from the theory of electrostatics, and says that a particle of charge q in an electric field E experiences an electric force:

The second term is the magnetic force:[11]

Using the definition of the cross product, the magnetic force can also be written as a scalar equation:[10]: 357 where Fmagnetic, v, and B are the scalar magnitude of their respective vectors, and θ is the angle between the velocity of the particle and the magnetic field. The vector B is defined as the vector field necessary to make the Lorentz force law correctly describe the motion of a charged particle. In other words,[10]: 173–4

[T]he command, "Measure the direction and magnitude of the vector B at such and such a place," calls for the following operations: Take a particle of known charge q. Measure the force on q at rest, to determine E. Then measure the force on the particle when its velocity is v; repeat with v in some other direction. Now find a B that makes the Lorentz force law fit all these results—that is the magnetic field at the place in question.

The B field can also be defined by the torque on a magnetic dipole, m.[12]: 174

The SI unit of B is tesla (symbol: T).[note 4] The Gaussian-cgs unit of B is the gauss (symbol: G). (The conversion is 1 T ≘ 10000 G.[13][14]) One nanotesla corresponds to 1 gamma (symbol: γ).[14]

The H-field

[edit]| Alternative names for H[8] |

|---|

The magnetic H field is defined:[11]: 269 [12]: 192 [2]: ch36

where is the vacuum permeability, and M is the magnetization vector. In a vacuum, B and H are proportional to each other. Inside a material they are different (see H and B inside and outside magnetic materials). The SI unit of the H-field is the ampere per metre (A/m),[15] and the CGS unit is the oersted (Oe).[13][10]: 286

Measurement

[edit]An instrument used to measure the local magnetic field is known as a magnetometer. Important classes of magnetometers include using induction magnetometers (or search-coil magnetometers) which measure only varying magnetic fields, rotating coil magnetometers, Hall effect magnetometers, NMR magnetometers, SQUID magnetometers, and fluxgate magnetometers. The magnetic fields of distant astronomical objects are measured through their effects on local charged particles. For instance, electrons spiraling around a field line produce synchrotron radiation that is detectable in radio waves. The finest precision for a magnetic field measurement was attained by Gravity Probe B at 5 aT (5×10−18 T).[16]

Visualization

[edit]Right: compass needles point in the direction of the local magnetic field, towards a magnet's south pole and away from its north pole.

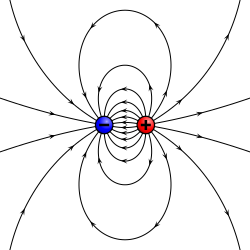

The field can be visualized by a set of magnetic field lines, that follow the direction of the field at each point. The lines can be constructed by measuring the strength and direction of the magnetic field at a large number of points (or at every point in space). Then, mark each location with an arrow (called a vector) pointing in the direction of the local magnetic field with its magnitude proportional to the strength of the magnetic field. Connecting these arrows then forms a set of magnetic field lines. The direction of the magnetic field at any point is parallel to the direction of nearby field lines, and the local density of field lines can be made proportional to its strength. Magnetic field lines are like streamlines in fluid flow, in that they represent a continuous distribution, and a different resolution would show more or fewer lines.

An advantage of using magnetic field lines as a representation is that many laws of magnetism (and electromagnetism) can be stated completely and concisely using simple concepts such as the "number" of field lines through a surface. These concepts can be quickly "translated" to their mathematical form. For example, the number of field lines through a given surface is the surface integral of the magnetic field.[10]: 237

Various phenomena "display" magnetic field lines as though the field lines were physical phenomena. For example, iron filings placed in a magnetic field form lines that correspond to "field lines".[note 5] Magnetic field "lines" are also visually displayed in polar auroras, in which plasma particle dipole interactions create visible streaks of light that line up with the local direction of Earth's magnetic field.

Field lines can be used as a qualitative tool to visualize magnetic forces. In ferromagnetic substances like iron and in plasmas, magnetic forces can be understood by imagining that the field lines exert a tension, (like a rubber band) along their length, and a pressure perpendicular to their length on neighboring field lines. "Unlike" poles of magnets attract because they are linked by many field lines; "like" poles repel because their field lines do not meet, but run parallel, pushing on each other.

Magnetic field of permanent magnets

[edit]Permanent magnets are objects that produce their own persistent magnetic fields. They are made of ferromagnetic materials, such as iron and nickel, that have been magnetized, and they have both a north and a south pole.

The magnetic field of permanent magnets can be quite complicated, especially near the magnet. The magnetic field of a small[note 6] straight magnet is proportional to the magnet's strength (called its magnetic dipole moment m). The equations are non-trivial and depend on the distance from the magnet and the orientation of the magnet. For simple magnets, m points in the direction of a line drawn from the south to the north pole of the magnet. Flipping a bar magnet is equivalent to rotating its m by 180 degrees.

The magnetic field of larger magnets can be obtained by modeling them as a collection of a large number of small magnets called dipoles each having their own m. The magnetic field produced by the magnet then is the net magnetic field of these dipoles; any net force on the magnet is a result of adding up the forces on the individual dipoles.

There are two simplified models for the nature of these dipoles: the magnetic pole model and the Amperian loop model. These two models produce two different magnetic fields, H and B. Outside a material, though, the two are identical (to a multiplicative constant) so that in many cases the distinction can be ignored. This is particularly true for magnetic fields, such as those due to electric currents, that are not generated by magnetic materials.

A realistic model of magnetism is more complicated than either of these models; neither model fully explains why materials are magnetic. The monopole model has no experimental support. The Amperian loop model explains some, but not all of a material's magnetic moment. The model predicts that the motion of electrons within an atom are connected to those electrons' orbital magnetic dipole moment, and these orbital moments do contribute to the magnetism seen at the macroscopic level. However, the motion of electrons is not classical, and the spin magnetic moment of electrons (which is not explained by either model) is also a significant contribution to the total moment of magnets.

Magnetic pole model

[edit]

Historically, early physics textbooks would model the force and torques between two magnets as due to magnetic poles repelling or attracting each other in the same manner as the Coulomb force between electric charges. At the microscopic level, this model contradicts the experimental evidence, and the pole model of magnetism is no longer the typical way to introduce the concept.[11]: 258 However, it is still sometimes used as a macroscopic model for ferromagnetism due to its mathematical simplicity.[17]

In this model, a magnetic H-field is produced by fictitious magnetic charges that are spread over the surface of each pole. These magnetic charges are in fact related to the magnetization field M. The H-field, therefore, is analogous to the electric field E, which starts at a positive electric charge and ends at a negative electric charge. Near the north pole, therefore, all H-field lines point away from the north pole (whether inside the magnet or out) while near the south pole all H-field lines point toward the south pole (whether inside the magnet or out). Too, a north pole feels a force in the direction of the H-field while the force on the south pole is opposite to the H-field.

In the magnetic pole model, the elementary magnetic dipole m is formed by two opposite magnetic poles of pole strength qm separated by a small distance vector d, such that m = qm d. The magnetic pole model predicts correctly the field H both inside and outside magnetic materials, in particular the fact that H is opposite to the magnetization field M inside a permanent magnet.

Since it is based on the fictitious idea of a magnetic charge density, the pole model has limitations. Magnetic poles cannot exist apart from each other as electric charges can, but always come in north–south pairs. If a magnetized object is divided in half, a new pole appears on the surface of each piece, so each has a pair of complementary poles. The magnetic pole model does not account for magnetism that is produced by electric currents, nor the inherent connection between angular momentum and magnetism.

The pole model usually treats magnetic charge as a mathematical abstraction, rather than a physical property of particles. However, a magnetic monopole is a hypothetical particle (or class of particles) that physically has only one magnetic pole (either a north pole or a south pole). In other words, it would possess a "magnetic charge" analogous to an electric charge. Magnetic field lines would start or end on magnetic monopoles, so if they exist, they would give exceptions to the rule that magnetic field lines neither start nor end. Some theories (such as Grand Unified Theories) have predicted the existence of magnetic monopoles, but so far, none have been observed.

Amperian loop model

[edit]In the model developed by Ampere, the elementary magnetic dipole that makes up all magnets is a sufficiently small Amperian loop with current I and loop area A. The dipole moment of this loop is m = IA.

These magnetic dipoles produce a magnetic B-field.

The magnetic field of a magnetic dipole is depicted in the figure. From outside, the ideal magnetic dipole is identical to that of an ideal electric dipole of the same strength. Unlike the electric dipole, a magnetic dipole is properly modeled as a current loop having a current I and an area a. Such a current loop has a magnetic moment of where the direction of m is perpendicular to the area of the loop and depends on the direction of the current using the right-hand rule. An ideal magnetic dipole is modeled as a real magnetic dipole whose area a has been reduced to zero and its current I increased to infinity such that the product m = Ia is finite. This model clarifies the connection between angular momentum and magnetic moment, which is the basis of the Einstein–de Haas effect rotation by magnetization and its inverse, the Barnett effect or magnetization by rotation.[18] Rotating the loop faster (in the same direction) increases the current and therefore the magnetic moment, for example.

Interactions with magnets

[edit]Force between magnets

[edit]Specifying the force between two small magnets is quite complicated because it depends on the strength and orientation of both magnets and their distance and direction relative to each other. The force is particularly sensitive to rotations of the magnets due to magnetic torque. The force on each magnet depends on its magnetic moment and the magnetic field[note 7] of the other.

To understand the force between magnets, it is useful to examine the magnetic pole model given above. In this model, the H-field of one magnet pushes and pulls on both poles of a second magnet. If this H-field is the same at both poles of the second magnet then there is no net force on that magnet since the force is opposite for opposite poles. If, however, the magnetic field of the first magnet is nonuniform (such as the H near one of its poles), each pole of the second magnet sees a different field and is subject to a different force. This difference in the two forces moves the magnet in the direction of increasing magnetic field and may also cause a net torque.

This is a specific example of a general rule that magnets are attracted (or repulsed depending on the orientation of the magnet) into regions of higher magnetic field. Any non-uniform magnetic field, whether caused by permanent magnets or electric currents, exerts a force on a small magnet in this way.

The details of the Amperian loop model are different and more complicated but yield the same result: that magnetic dipoles are attracted/repelled into regions of higher magnetic field. Mathematically, the force on a small magnet having a magnetic moment m due to a magnetic field B is:[19]: Eq. 11.42

where the gradient ∇ is the change of the quantity m · B per unit distance and the direction is that of maximum increase of m · B. The dot product m · B = mBcos(θ), where m and B represent the magnitude of the m and B vectors and θ is the angle between them. If m is in the same direction as B then the dot product is positive and the gradient points "uphill" pulling the magnet into regions of higher B-field (more strictly larger m · B). This equation is strictly only valid for magnets of zero size, but is often a good approximation for not too large magnets. The magnetic force on larger magnets is determined by dividing them into smaller regions each having their own m then summing up the forces on each of these very small regions.

Magnetic torque on permanent magnets

[edit]If two like poles of two separate magnets are brought near each other, and one of the magnets is allowed to turn, it promptly rotates to align itself with the first. In this example, the magnetic field of the stationary magnet creates a magnetic torque on the magnet that is free to rotate. This magnetic torque τ tends to align a magnet's poles with the magnetic field lines. A compass, therefore, turns to align itself with Earth's magnetic field.

In terms of the pole model, two equal and opposite magnetic charges experiencing the same H also experience equal and opposite forces. Since these equal and opposite forces are in different locations, this produces a torque proportional to the distance (perpendicular to the force) between them. With the definition of m as the pole strength times the distance between the poles, this leads to τ = μ0 m H sin θ, where μ0 is a constant called the vacuum permeability, measuring 4π×10−7 V·s/(A·m) and θ is the angle between H and m.

Mathematically, the torque τ on a small magnet is proportional both to the applied magnetic field and to the magnetic moment m of the magnet:

where × represents the vector cross product. This equation includes all of the qualitative information included above. There is no torque on a magnet if m is in the same direction as the magnetic field, since the cross product is zero for two vectors that are in the same direction. Further, all other orientations feel a torque that twists them toward the direction of magnetic field.

Interactions with electric currents

[edit]Currents of electric charges both generate a magnetic field and feel a force due to magnetic B-fields.

Magnetic field due to moving charges and electric currents

[edit]

All moving charged particles produce magnetic fields. Moving point charges, such as electrons, produce complicated but well known magnetic fields that depend on the charge, velocity, and acceleration of the particles.[20]

Magnetic field lines form in concentric circles around a cylindrical current-carrying conductor, such as a length of wire. The direction of such a magnetic field can be determined by using the "right-hand grip rule" (see figure at right). The strength of the magnetic field decreases with distance from the wire. (For an infinite length wire the strength is inversely proportional to the distance.)

Bending a current-carrying wire into a loop concentrates the magnetic field inside the loop while weakening it outside. Bending a wire into multiple closely spaced loops to form a coil or "solenoid" enhances this effect. A device so formed around an iron core may act as an electromagnet, generating a strong, well-controlled magnetic field. An infinitely long cylindrical electromagnet has a uniform magnetic field inside, and no magnetic field outside. A finite length electromagnet produces a magnetic field that looks similar to that produced by a uniform permanent magnet, with its strength and polarity determined by the current flowing through the coil.

The magnetic field generated by a steady current I (a constant flow of electric charges, in which charge neither accumulates nor is depleted at any point)[note 8] is described by the Biot–Savart law:[21]: 224 where the integral sums over the wire length where vector dℓ is the vector line element with direction in the same sense as the current I, μ0 is the magnetic constant, r is the distance between the location of dℓ and the location where the magnetic field is calculated, and r̂ is a unit vector in the direction of r. For example, in the case of a sufficiently long, straight wire, this becomes: where r = |r|. The direction is tangent to a circle perpendicular to the wire according to the right hand rule.[21]: 225

A slightly more general[22][note 9] way of relating the current to the B-field is through Ampère's law: where the line integral is over any arbitrary loop and is the current enclosed by that loop. Ampère's law is always valid for steady currents and can be used to calculate the B-field for certain highly symmetric situations such as an infinite wire or an infinite solenoid.

In a modified form that accounts for time varying electric fields, Ampère's law is one of four Maxwell's equations that describe electricity and magnetism.

Force on moving charges and current

[edit]Force on a charged particle

[edit]A charged particle moving in a B-field experiences a sideways force that is proportional to the strength of the magnetic field, the component of the velocity that is perpendicular to the magnetic field and the charge of the particle. This force is known as the Lorentz force, and is given by where F is the force, q is the electric charge of the particle, v is the instantaneous velocity of the particle, and B is the magnetic field (in teslas).

The Lorentz force is always perpendicular to both the velocity of the particle and the magnetic field that created it. When a charged particle moves in a static magnetic field, it traces a helical path in which the helix axis is parallel to the magnetic field, and in which the speed of the particle remains constant. Because the magnetic force is always perpendicular to the motion, the magnetic field can do no work on an isolated charge.[23][24] It can only do work indirectly, via the electric field generated by a changing magnetic field. It is often claimed that the magnetic force can do work to a non-elementary magnetic dipole, or to charged particles whose motion is constrained by other forces, but this is incorrect[25] because the work in those cases is performed by the electric forces of the charges deflected by the magnetic field.

Force on current-carrying wire

[edit]The force on a current carrying wire is similar to that of a moving charge as expected since a current carrying wire is a collection of moving charges. A current-carrying wire feels a force in the presence of a magnetic field. The Lorentz force on a macroscopic current is often referred to as the Laplace force. Consider a conductor of length ℓ, cross section A, and charge q due to electric current i. If this conductor is placed in a magnetic field of magnitude B that makes an angle θ with the velocity of charges in the conductor, the force exerted on a single charge q is so, for N charges where the force exerted on the conductor is where i = nqvA.

Relation between H and B

[edit]The formulas derived for the magnetic field above are correct when dealing with the entire current. A magnetic material placed inside a magnetic field, though, generates its own bound current, which can be a challenge to calculate. (This bound current is due to the sum of atomic sized current loops and the spin of the subatomic particles such as electrons that make up the material.) The H-field as defined above helps factor out this bound current; but to see how, it helps to introduce the concept of magnetization first.

Magnetization

[edit]The magnetization vector field M represents how strongly a region of material is magnetized. It is defined as the net magnetic dipole moment per unit volume of that region. The magnetization of a uniform magnet is therefore a material constant, equal to the magnetic moment m of the magnet divided by its volume. Since the SI unit of magnetic moment is A⋅m2, the SI unit of magnetization M is ampere per meter, identical to that of the H-field.

The magnetization M field of a region points in the direction of the average magnetic dipole moment in that region. Magnetization field lines, therefore, begin near the magnetic south pole and ends near the magnetic north pole. (Magnetization does not exist outside the magnet.)

In the Amperian loop model, the magnetization is due to combining many tiny Amperian loops to form a resultant current called bound current. This bound current, then, is the source of the magnetic B field due to the magnet. Given the definition of the magnetic dipole, the magnetization field follows a similar law to that of Ampere's law:[26] where the integral is a line integral over any closed loop and Ib is the bound current enclosed by that closed loop.

In the magnetic pole model, magnetization begins at and ends at magnetic poles. If a given region, therefore, has a net positive "magnetic pole strength" (corresponding to a north pole) then it has more magnetization field lines entering it than leaving it. Mathematically this is equivalent to: where the integral is a closed surface integral over the closed surface S and qM is the "magnetic charge" (in units of magnetic flux) enclosed by S. (A closed surface completely surrounds a region with no holes to let any field lines escape.) The negative sign occurs because the magnetization field moves from south to north.

H-field and magnetic materials

[edit]

In SI units, the H-field is related to the B-field by

In terms of the H-field, Ampere's law is where If represents the 'free current' enclosed by the loop so that the line integral of H does not depend at all on the bound currents.[27]

For the differential equivalent of this equation see Maxwell's equations. Ampere's law leads to the boundary condition where Kf is the surface free current density and the unit normal points in the direction from medium 2 to medium 1.[28]

Similarly, a surface integral of H over any closed surface is independent of the free currents and picks out the "magnetic charges" within that closed surface:

which does not depend on the free currents.

The H-field, therefore, can be separated into two[note 10] independent parts:

where H0 is the applied magnetic field due only to the free currents and Hd is the demagnetizing field due only to the bound currents.

The magnetic H-field, therefore, re-factors the bound current in terms of "magnetic charges". The H field lines loop only around "free current" and, unlike the magnetic B field, begins and ends near magnetic poles as well.

Magnetism

[edit]Most materials respond to an applied B-field by producing their own magnetization M and therefore their own B-fields. Typically, the response is weak and exists only when the magnetic field is applied. The term magnetism describes how materials respond on the microscopic level to an applied magnetic field and is used to categorize the magnetic phase of a material. Materials are divided into groups based upon their magnetic behavior:

- Diamagnetic materials[29] produce a magnetization that opposes the magnetic field.

- Paramagnetic materials[29] produce a magnetization in the same direction as the applied magnetic field.

- Ferromagnetic materials and the closely related ferrimagnetic materials and antiferromagnetic materials[30][31] can have a magnetization independent of an applied B-field with a complex relationship between the two fields.

- Superconductors (and ferromagnetic superconductors)[32][33] are materials that are characterized by perfect conductivity below a critical temperature and magnetic field. They also are highly magnetic and can be perfect diamagnets below a lower critical magnetic field. Superconductors often have a broad range of temperatures and magnetic fields (the so-named mixed state) under which they exhibit a complex hysteretic dependence of M on B.

In the case of paramagnetism and diamagnetism, the magnetization M is often proportional to the applied magnetic field such that: where μ is a material dependent parameter called the permeability. In some cases the permeability may be a second rank tensor so that H may not point in the same direction as B. These relations between B and H are examples of constitutive equations. However, superconductors and ferromagnets have a more complex B-to-H relation; see magnetic hysteresis.

Stored energy

[edit]Energy is needed to generate a magnetic field both to work against the electric field that a changing magnetic field creates and to change the magnetization of any material within the magnetic field. For non-dispersive materials, this same energy is released when the magnetic field is destroyed so that the energy can be modeled as being stored in the magnetic field.

For linear, non-dispersive, materials (such that B = μH where μ is frequency-independent), the energy density is:

If there are no magnetic materials around then μ can be replaced by μ0. The above equation cannot be used for nonlinear materials, though; a more general expression given below must be used.

In general, the incremental amount of work per unit volume δW needed to cause a small change of magnetic field δB is:

Once the relationship between H and B is known this equation is used to determine the work needed to reach a given magnetic state. For hysteretic materials such as ferromagnets and superconductors, the work needed also depends on how the magnetic field is created. For linear non-dispersive materials, though, the general equation leads directly to the simpler energy density equation given above.

Appearance in Maxwell's equations

[edit]Like all vector fields, a magnetic field has two important mathematical properties that relates it to its sources. (For B the sources are currents and changing electric fields.) These two properties, along with the two corresponding properties of the electric field, make up Maxwell's Equations. Maxwell's Equations together with the Lorentz force law form a complete description of classical electrodynamics including both electricity and magnetism.

The first property is the divergence of a vector field A, ∇ · A, which represents how A "flows" outward from a given point. As discussed above, a B-field line never starts or ends at a point but instead forms a complete loop. This is mathematically equivalent to saying that the divergence of B is zero. (Such vector fields are called solenoidal vector fields.) This property is called Gauss's law for magnetism and is equivalent to the statement that there are no isolated magnetic poles or magnetic monopoles.

The second mathematical property is called the curl, such that ∇ × A represents how A curls or "circulates" around a given point. The result of the curl is called a "circulation source". The equations for the curl of B and of E are called the Ampère–Maxwell equation and Faraday's law respectively.

Gauss' law for magnetism

[edit]One important property of the B-field produced this way is that magnetic B-field lines neither start nor end (mathematically, B is a solenoidal vector field); a field line may only extend to infinity, or wrap around to form a closed curve, or follow a never-ending (possibly chaotic) path.[34] Magnetic field lines exit a magnet near its north pole and enter near its south pole, but inside the magnet B-field lines continue through the magnet from the south pole back to the north.[note 11] If a B-field line enters a magnet somewhere it has to leave somewhere else; it is not allowed to have an end point.

More formally, since all the magnetic field lines that enter any given region must also leave that region, subtracting the "number"[note 12] of field lines that enter the region from the number that exit gives identically zero. Mathematically this is equivalent to Gauss's law for magnetism: where the integral is a surface integral over the closed surface S (a closed surface is one that completely surrounds a region with no holes to let any field lines escape). Since dA points outward, the dot product in the integral is positive for B-field pointing out and negative for B-field pointing in.

Faraday's Law

[edit]A changing magnetic field, such as a magnet moving through a conducting coil, generates an electric field (and therefore tends to drive a current in such a coil). This is known as Faraday's law and forms the basis of many electrical generators and electric motors. Mathematically, Faraday's law is:

where is the electromotive force (or EMF, the voltage generated around a closed loop) and Φ is the magnetic flux—the product of the area times the magnetic field normal to that area. (This definition of magnetic flux is why B is often referred to as magnetic flux density.)[35]: 210 The negative sign represents the fact that any current generated by a changing magnetic field in a coil produces a magnetic field that opposes the change in the magnetic field that induced it. This phenomenon is known as Lenz's law. This integral formulation of Faraday's law can be converted[note 13] into a differential form, which applies under slightly different conditions.

Ampère's Law and Maxwell's correction

[edit]Similar to the way that a changing magnetic field generates an electric field, a changing electric field generates a magnetic field. This fact is known as Maxwell's correction to Ampère's law and is applied as an additive term to Ampere's law as given above. This additional term is proportional to the time rate of change of the electric flux and is similar to Faraday's law above but with a different and positive constant out front. (The electric flux through an area is proportional to the area times the perpendicular part of the electric field.)

The full law including the correction term is known as the Maxwell–Ampère equation. It is not commonly given in integral form because the effect is so small that it can typically be ignored in most cases where the integral form is used.

The Maxwell term is critically important in the creation and propagation of electromagnetic waves. Maxwell's correction to Ampère's Law together with Faraday's law of induction describes how mutually changing electric and magnetic fields interact to sustain each other and thus to form electromagnetic waves, such as light: a changing electric field generates a changing magnetic field, which generates a changing electric field again. These, though, are usually described using the differential form of this equation given below.

where J is the complete microscopic current density, and ε0 is the vacuum permittivity.

As discussed above, materials respond to an applied electric E field and an applied magnetic B field by producing their own internal "bound" charge and current distributions that contribute to E and B but are difficult to calculate. To circumvent this problem, H and D fields are used to re-factor Maxwell's equations in terms of the free current density Jf:

These equations are not any more general than the original equations (if the "bound" charges and currents in the material are known). They also must be supplemented by the relationship between B and H as well as that between E and D. On the other hand, for simple relationships between these quantities this form of Maxwell's equations can circumvent the need to calculate the bound charges and currents.

Formulation in special relativity and quantum electrodynamics

[edit]Relativistic electrodynamics

[edit]As different aspects of the same phenomenon

[edit]According to the special theory of relativity, the partition of the electromagnetic force into separate electric and magnetic components is not fundamental, but varies with the observational frame of reference: An electric force perceived by one observer may be perceived by another (in a different frame of reference) as a magnetic force, or a mixture of electric and magnetic forces.

The magnetic field existing as electric field in other frames can be shown by consistency of equations obtained from Lorentz transformation of four force from Coulomb's Law in particle's rest frame with Maxwell's laws considering definition of fields from Lorentz force[broken anchor] and for non accelerating condition. The form of magnetic field hence obtained by Lorentz transformation of four-force from the form of Coulomb's law in source's initial frame is given by:[36]: 29–42

where is the charge of the point source, is the vacuum permittivity, is the position vector from the point source to the point in space, is the velocity vector of the charged particle, is the ratio of speed of the charged particle divided by the speed of light and is the angle between and . This form of magnetic field can be shown to satisfy Maxwell's laws within the constraint of particle being non accelerating.[37] The above reduces to Biot-Savart law for non relativistic stream of current ().

Formally, special relativity combines the electric and magnetic fields into a rank-2 tensor, called the electromagnetic tensor. Changing reference frames mixes these components. This is analogous to the way that special relativity mixes space and time into spacetime, and mass, momentum, and energy into four-momentum.[38] Similarly, the energy stored in a magnetic field is mixed with the energy stored in an electric field in the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor.

Magnetic vector potential

[edit]In advanced topics such as quantum mechanics and relativity it is often easier to work with a potential formulation of electrodynamics rather than in terms of the electric and magnetic fields. In this representation, the magnetic vector potential A, and the electric scalar potential φ, are defined using gauge fixing such that:

The vector potential, A given by this form may be interpreted as a generalized potential momentum per unit charge [39] just as φ is interpreted as a generalized potential energy per unit charge. There are multiple choices one can make for the potential fields that satisfy the above condition. However, the choice of potentials is represented by its respective gauge condition.

Maxwell's equations when expressed in terms of the potentials in Lorenz gauge can be cast into a form that agrees with special relativity.[40] In relativity, A together with φ forms a four-potential regardless of the gauge condition, analogous to the four-momentum that combines the momentum and energy of a particle. Using the four potential instead of the electromagnetic tensor has the advantage of being much simpler—and it can be easily modified to work with quantum mechanics.

Propagation of Electric and Magnetic fields

[edit]Special theory of relativity imposes the condition for events related by cause and effect to be time-like separated, that is that causal efficacy propagates no faster than light.[41] Maxwell's equations for electromagnetism are found to be in favor of this as electric and magnetic disturbances are found to travel at the speed of light in space. Electric and magnetic fields from classical electrodynamics obey the principle of locality in physics and are expressed in terms of retarded time or the time at which the cause of a measured field originated given that the influence of field travelled at speed of light. The retarded time for a point particle is given as solution of:

where is retarded time or the time at which the source's contribution of the field originated, is the position vector of the particle as function of time, is the point in space, is the time at which fields are measured and is the speed of light. The equation subtracts the time taken for light to travel from particle to the point in space from the time of measurement to find time of origin of the fields. The uniqueness of solution for for given , and is valid for charged particles moving slower than speed of light.[36]

Magnetic field of arbitrary moving point charge

[edit]The solution of maxwell's equations for electric and magnetic field of a point charge is expressed in terms of retarded time or the time at which the particle in the past causes the field at the point, given that the influence travels across space at the speed of light.

Any arbitrary motion of point charge causes electric and magnetic fields found by solving maxwell's equations using green's function for retarded potentials and hence finding the fields to be as follows:

where and are electric scalar potential and magnetic vector potential in Lorentz gauge, is the charge of the point source, is a unit vector pointing from charged particle to the point in space, is the velocity of the particle divided by the speed of light and is the corresponding Lorentz factor. Hence by the principle of superposition, the fields of a system of charges also obey principle of locality.

Quantum electrodynamics

[edit]The classical electromagnetic field incorporated into quantum mechanics forms what is known as the semi-classical theory of radiation. However, it is not able to make experimentally observed predictions such as spontaneous emission process or Lamb shift implying the need for quantization of fields. In modern physics, the electromagnetic field is understood to be not a classical field, but rather a quantum field; it is represented not as a vector of three numbers at each point, but as a vector of three quantum operators at each point. The most accurate modern description of the electromagnetic interaction (and much else) is quantum electrodynamics (QED),[42] which is incorporated into a more complete theory known as the Standard Model of particle physics.

In QED, the magnitude of the electromagnetic interactions between charged particles (and their antiparticles) is computed using perturbation theory. These rather complex formulas produce a remarkable pictorial representation as Feynman diagrams in which virtual photons are exchanged.

Predictions of QED agree with experiments to an extremely high degree of accuracy: currently about 10−12 (and limited by experimental errors); for details see precision tests of QED. This makes QED one of the most accurate physical theories constructed thus far.

All equations in this article are in the classical approximation, which is less accurate than the quantum description mentioned here. However, under most everyday circumstances, the difference between the two theories is negligible.

Uses and examples

[edit]Earth's magnetic field

[edit]

The Earth's magnetic field is produced by convection of a liquid iron alloy in the outer core. In a dynamo process, the movements drive a feedback process in which electric currents create electric and magnetic fields that in turn act on the currents.[43]

The field at the surface of the Earth is approximately the same as if a giant bar magnet were positioned at the center of the Earth and tilted at an angle of about 11° off the rotational axis of the Earth (see the figure).[44] The north pole of a magnetic compass needle points roughly north, toward the North Magnetic Pole. However, because a magnetic pole is attracted to its opposite, the North Magnetic Pole is actually the south pole of the geomagnetic field. This confusion in terminology arises because the pole of a magnet is defined by the geographical direction it points.[45]

Earth's magnetic field is not constant—the strength of the field and the location of its poles vary.[46] Moreover, the poles periodically reverse their orientation in a process called geomagnetic reversal. The most recent reversal occurred 780,000 years ago.[47]

Rotating magnetic fields

[edit]The rotating magnetic field is a common design principle in the operation of alternating-current motors. A permanent magnet in such a field rotates so as to maintain its alignment with the external field.

Magnetic torque is used to drive electric motors. In one simple motor design, a magnet is fixed to a freely rotating shaft and is subjected to a magnetic field from an array of electromagnets. By continuously switching the electric current through each of the electromagnets, thereby flipping the polarity of their magnetic fields, like poles are kept next to the rotor; the resultant torque is transferred to the shaft.

A rotating magnetic field can be constructed using two coils at right angles with a phase difference of 90 degrees between their AC currents. In practice, three-phase systems are used where the three currents are equal in magnitude and have a phase difference of 120 degrees. Three similar coils at mutual geometrical angles of 120 degrees create the rotating magnetic field. The ability of the three-phase system to create a rotating field, utilized in electric motors, is one of the main reasons why three-phase systems dominate the world's electrical power supply systems.

Synchronous motors use DC-voltage-fed rotor windings, which lets the excitation of the machine be controlled—and induction motors use short-circuited rotors (instead of a magnet) following the rotating magnetic field of a multicoiled stator. The short-circuited turns of the rotor develop eddy currents induced by the rotating field of the stator, and these currents in turn produce a torque on the rotor through the Lorentz force.

The Italian physicist Galileo Ferraris and the Serbian-American electrical engineer Nikola Tesla independently researched the use of rotating magnetic fields in electric motors. In 1888, Ferraris published his research in a paper to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin and Tesla gained U.S. patent 381,968 for his work.

Hall effect

[edit]The charge carriers of a current-carrying conductor placed in a transverse magnetic field experience a sideways Lorentz force; this results in a charge separation in a direction perpendicular to the current and to the magnetic field. The resultant voltage in that direction is proportional to the applied magnetic field. This is known as the Hall effect.

The Hall effect is often used to measure the magnitude of a magnetic field. It is used as well to find the sign of the dominant charge carriers in materials such as semiconductors (negative electrons or positive holes).

Magnetic circuits

[edit]An important use of H is in magnetic circuits where B = μH inside a linear material. Here, μ is the magnetic permeability of the material. This result is similar in form to Ohm's law J = σE, where J is the current density, σ is the conductance and E is the electric field. Extending this analogy, the counterpart to the macroscopic Ohm's law (I = V⁄R) is:

where is the magnetic flux in the circuit, is the magnetomotive force applied to the circuit, and Rm is the reluctance of the circuit. Here the reluctance Rm is a quantity similar in nature to resistance for the flux. Using this analogy it is straightforward to calculate the magnetic flux of complicated magnetic field geometries, by using all the available techniques of circuit theory.

Largest magnitude magnetic fields

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (July 2021) |

As of October 2018[update], the largest magnitude magnetic field produced over a macroscopic volume outside a lab setting is 2.8 kT (VNIIEF in Sarov, Russia, 1998).[48][49] As of October 2018, the largest magnitude magnetic field produced in a laboratory over a macroscopic volume was 1.2 kT by researchers at the University of Tokyo in 2018.[49] The largest magnitude magnetic fields produced in a laboratory occur in particle accelerators, such as RHIC, inside the collisions of heavy ions, where microscopic fields reach 1014 T.[50][51] Magnetars have the strongest known magnetic fields of any naturally occurring object, ranging from 0.1 to 100 GT (108 to 1011 T).[52]

Common formulæ

[edit]| Current configuration | Figure | Magnetic field | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finite beam of current |

|

where is the uniform current throughout the beam, with the direction of magnetic field as shown. | |

| Infinite wire |

|

where is the uniform current flowing through the wire with the direction of magnetic field as shown. | |

| Infinite cylindrical wire |

|

outside the wire carrying a current uniformly, with the direction of magnetic field as shown. |

inside the wire carrying a current uniformly, with the direction of magnetic field as shown. |

| Circular loop |

|

along the axis of the loop, where is the uniform current flowing through the loop. | |

| Solenoid |

|

along the axis of the solenoid carrying current with , uniform number of loops of currents per length of solenoid; and the direction of magnetic field as shown. | |

| Infinite solenoid |

|

outside the solenoid carrying current with , uniform number of loops of currents per length of solenoid. |

inside the solenoid carrying current with , uniform number of loops of currents per length of solenoid, with the direction of magnetic field as shown. |

| Circular Toroid |

|

along the bulk of the circular toroid carrying uniform current through number of uniformly distributed poloidal loops, with the direction of magnetic field as indicated. | |

| Magnetic Dipole |

|

on the equatorial plane, where is the magnetic dipole moment. |

on the axial plane (given that ), where can also be negative to indicate position at the opposite direction on the axis, and is the magnetic dipole moment. |

Additional magnetic field values can be found through the magnetic field of a finite beam, for example, that the magnetic field of an arc of angle and radius at the center is , or that the magnetic field at the center of a N-sided regular polygon of side is , both outside of the plane with proper directions as inferred by right hand thumb rule.

History

[edit]

Early developments

[edit]While magnets and some properties of magnetism were known to ancient societies, the research of magnetic fields began in 1269 when French scholar Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt mapped out the magnetic field on the surface of a spherical magnet using iron needles. Noting the resulting field lines crossed at two points he named those points "poles" in analogy to Earth's poles. He also articulated the principle that magnets always have both a north and south pole, no matter how finely one slices them.[53][note 14]

Almost three centuries later, William Gilbert of Colchester replicated Petrus Peregrinus' work and was the first to state explicitly that Earth is a magnet.[54]: 34 Published in 1600, Gilbert's work, De Magnete, helped to establish magnetism as a science.

Mathematical development

[edit]

In 1750, John Michell stated that magnetic poles attract and repel in accordance with an inverse square law[54]: 56 Charles-Augustin de Coulomb experimentally verified this in 1785 and stated explicitly that north and south poles cannot be separated.[54]: 59 Building on this force between poles, Siméon Denis Poisson (1781–1840) created the first successful model of the magnetic field, which he presented in 1824.[54]: 64 In this model, a magnetic H-field is produced by magnetic poles and magnetism is due to small pairs of north–south magnetic poles.

Three discoveries in 1820 challenged this foundation of magnetism. Hans Christian Ørsted demonstrated that a current-carrying wire is surrounded by a circular magnetic field.[note 15][55] Then André-Marie Ampère showed that parallel wires with currents attract one another if the currents are in the same direction and repel if they are in opposite directions.[54]: 87 [56] Finally, Jean-Baptiste Biot and Félix Savart announced empirical results about the forces that a current-carrying long, straight wire exerted on a small magnet, determining the forces were inversely proportional to the perpendicular distance from the wire to the magnet.[57][54]: 86 Laplace later deduced a law of force based on the differential action of a differential section of the wire,[57][58] which became known as the Biot–Savart law, as Laplace did not publish his findings.[59]

Extending these experiments, Ampère published his own successful model of magnetism in 1825. In it, he showed the equivalence of electrical currents to magnets[54]: 88 and proposed that magnetism is due to perpetually flowing loops of current instead of the dipoles of magnetic charge in Poisson's model.[note 16] Further, Ampère derived both Ampère's force law describing the force between two currents and Ampère's law, which, like the Biot–Savart law, correctly described the magnetic field generated by a steady current. Also in this work, Ampère introduced the term electrodynamics to describe the relationship between electricity and magnetism.[54]: 88–92

In 1831, Michael Faraday discovered electromagnetic induction when he found that a changing magnetic field generates an encircling electric field, formulating what is now known as Faraday's law of induction.[54]: 189–192 Later, Franz Ernst Neumann proved that, for a moving conductor in a magnetic field, induction is a consequence of Ampère's force law.[54]: 222 In the process, he introduced the magnetic vector potential, which was later shown to be equivalent to the underlying mechanism proposed by Faraday.[54]: 225

In 1850, Lord Kelvin, then known as William Thomson, distinguished between two magnetic fields now denoted H and B. The former applied to Poisson's model and the latter to Ampère's model and induction.[54]: 224 Further, he derived how H and B relate to each other and coined the term permeability.[54]: 245 [60]

Between 1861 and 1865, James Clerk Maxwell developed and published Maxwell's equations, which explained and united all of classical electricity and magnetism. The first set of these equations was published in a paper entitled On Physical Lines of Force in 1861. These equations were valid but incomplete. Maxwell completed his set of equations in his later 1865 paper A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field and demonstrated the fact that light is an electromagnetic wave. Heinrich Hertz published papers in 1887 and 1888 experimentally confirming this fact.[61][62]

Modern developments

[edit]In 1887, Tesla developed an induction motor that ran on alternating current. The motor used polyphase current, which generated a rotating magnetic field to turn the motor (a principle that Tesla claimed to have conceived in 1882).[63][64][65] Tesla received a patent for his electric motor in May 1888.[66][67] In 1885, Galileo Ferraris independently researched rotating magnetic fields and subsequently published his research in a paper to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin, just two months before Tesla was awarded his patent, in March 1888.[68]

The twentieth century showed that classical electrodynamics is already consistent with special relativity, and extended classical electrodynamics to work with quantum mechanics. Albert Einstein, in his paper of 1905 that established relativity, showed that both the electric and magnetic fields are part of the same phenomena viewed from different reference frames. Finally, the emergent field of quantum mechanics was merged with electrodynamics to form quantum electrodynamics, which first formalized the notion that electromagnetic field energy is quantized in the form of photons.

See also

[edit]General

[edit]- Magnetohydrodynamics – the study of the dynamics of electrically conducting fluids

- Magnetic hysteresis – application to ferromagnetism

- Magnetic nanoparticles – extremely small magnetic particles that are tens of atoms wide

- Magnetic reconnection – an effect that causes solar flares and auroras

- Magnetic scalar potential

- SI electromagnetism units – common units used in electromagnetism

- Orders of magnitude (magnetic field) – list of magnetic field sources and measurement devices from smallest magnetic fields to largest detected

- Upward continuation

- Moses Effect

Mathematics

[edit]- Magnetic helicity – extent to which a magnetic field wraps around itself

Applications

[edit]- Dynamo theory – a proposed mechanism for the creation of the Earth's magnetic field

- Helmholtz coil – a device for producing a region of nearly uniform magnetic field

- Magnetic field viewing film – Film used to view the magnetic field of an area

- Magnetic pistol – a device on torpedoes or naval mines that detect the magnetic field of their target

- Maxwell coil – a device for producing a large volume of an almost constant magnetic field

- Stellar magnetic field – a discussion of the magnetic field of stars

- Teltron tube – device used to display an electron beam and demonstrates effect of electric and magnetic fields on moving charges

Notes

[edit]- ^ The letters B and H were originally chosen by Maxwell in his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (Vol. II, pp. 236–237). For many quantities, he simply started choosing letters from the beginning of the alphabet. See Ralph Baierlein (2000). "Answer to Question #73. S is for entropy, Q is for charge". American Journal of Physics. 68 (8): 691. Bibcode:2000AmJPh..68..691B. doi:10.1119/1.19524.

- ^ Edward Purcell, in Electricity and Magnetism, McGraw-Hill, 1963, writes, Even some modern writers who treat B as the primary field feel obliged to call it the magnetic induction because the name magnetic field was historically preempted by H. This seems clumsy and pedantic. If you go into the laboratory and ask a physicist what causes the pion trajectories in his bubble chamber to curve, he'll probably answer "magnetic field", not "magnetic induction." You will seldom hear a geophysicist refer to the Earth's magnetic induction, or an astrophysicist talk about the magnetic induction of the galaxy. We propose to keep on calling B the magnetic field. As for H, although other names have been invented for it, we shall call it "the field H" or even "the magnetic field H." In a similar vein, M Gerloch (1983). Magnetism and Ligand-field Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-521-24939-3. says: "So we may think of both B and H as magnetic fields, but drop the word 'magnetic' from H so as to maintain the distinction ... As Purcell points out, 'it is only the names that give trouble, not the symbols'."

- ^ An alternative mnemonic to the right hand rule is Fleming's left-hand rule.

- ^ The SI unit of ΦB (magnetic flux) is the weber (symbol: Wb), related to the tesla by 1 Wb/m2 = 1 T. The SI unit tesla is equal to (newton·second)/(coulomb·metre). This can be seen from the magnetic part of the Lorentz force law.

- ^ The use of iron filings to display a field presents something of an exception to this picture; the filings alter the magnetic field so that it is much larger along the "lines" of iron, because of the large permeability of iron relative to air.

- ^ Here, "small" means that the observer is sufficiently far away from the magnet, so that the magnet can be considered as infinitesimally small. "Larger" magnets need to include more complicated terms in the mathematical expression of the magnetic field and depend on the entire geometry of the magnet not just m.

- ^ Either B or H may be used for the magnetic field outside the magnet.

- ^ In practice, the Biot–Savart law and other laws of magnetostatics are often used even when a current change in time, as long as it does not change too quickly. It is often used, for instance, for standard household currents, which oscillate sixty times per second.[21]: 223

- ^ The Biot–Savart law contains the additional restriction (boundary condition) that the B-field must go to zero fast enough at infinity. It also depends on the divergence of B being zero, which is always valid. (There are no magnetic charges.)

- ^ A third term is needed for changing electric fields and polarization currents; this displacement current term is covered in Maxwell's equations below.

- ^ To see that this must be true imagine placing a compass inside a magnet. There, the north pole of the compass points toward the north pole of the magnet since magnets stacked on each other point in the same direction.

- ^ As discussed above, magnetic field lines are primarily a conceptual tool used to represent the mathematics behind magnetic fields. The total "number" of field lines is dependent on how the field lines are drawn. In practice, integral equations such as the one that follows in the main text are used instead.

- ^ A complete expression for Faraday's law of induction in terms of the electric E and magnetic fields can be written as: where ∂Σ(t) is the moving closed path bounding the moving surface Σ(t), and dA is an element of surface area of Σ(t). The first integral calculates the work done moving a charge a distance dℓ based upon the Lorentz force law. In the case where the bounding surface is stationary, the Kelvin–Stokes theorem can be used to show this equation is equivalent to the Maxwell–Faraday equation.

- ^ His Epistola Petri Peregrini de Maricourt ad Sygerum de Foucaucourt Militem de Magnete, which is often shortened to Epistola de magnete, is dated 1269 C.E.

- ^ During a lecture demonstration on the effects of a current on a campus needle, Ørsted showed that when a current-carrying wire is placed at a right angle with the compass, nothing happens. When he tried to orient the wire parallel to the compass needle, however, it produced a pronounced deflection of the compass needle. By placing the compass on different sides of the wire, he was able to determine the field forms perfect circles around the wire.[54]: 85

- ^ From the outside, the field of a dipole of magnetic charge has exactly the same form as a current loop when both are sufficiently small. Therefore, the two models differ only for magnetism inside magnetic material.

References

[edit]- ^ Nave, Rod. "Magnetic Field". HyperPhysics. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Feynman, Richard P.; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Vol. 2. California Institute of Technology.

- ^ Young, Hugh D.; Freedman, Roger A.; Ford, A. Lewis (2008). Sears and Zemansky's university physics: with modern physics. Vol. 2. Pearson Addison-Wesley. pp. 918–919. ISBN 978-0-321-50121-9.

- ^ Purcell, Edward M.; Morin, David J. (2013). Electricity and Magnetism (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01402-2.

- ^ a b c d The International System of Units (PDF), V3.01 (9th ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, August 2024, ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0

- ^ Jiles, David C. (1998). Introduction to Magnetism and Magnetic Materials (2 ed.). CRC. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-412-79860-3.

- ^ John J. Roche (2000). "B and H, the intensity vectors of magnetism: A new approach to resolving a century-old controversy". American Journal of Physics. 68 (5): 438. Bibcode:2000AmJPh..68..438R. doi:10.1119/1.19459.

- ^ a b E. J. Rothwell and M. J. Cloud (2010) Electromagnetics. Taylor & Francis. p. 23. ISBN 1-4200-5826-6.

- ^ a b Stratton, Julius Adams (1941). Electromagnetic Theory (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-07-062150-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b c d e Purcell, E. (2011). Electricity and Magnetism (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01360-5.

- ^ a b c d Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 0-13-805326-X.

- ^ a b Jackson, John David (1998). Classical electrodynamics (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-30932-X.

- ^ a b "Non-SI units accepted for use with the SI, and units based on fundamental constants (contd.)". SI Brochure: The International System of Units (SI) [8th edition, 2006; updated in 2014]. Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ a b Lang, Kenneth R. (2006). A Companion to Astronomy and Astrophysics. Springer. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-387-33367-0. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "International system of units (SI)". NIST reference on constants, units, and uncertainty. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ "Gravity Probe B Executive Summary" (PDF). pp. 10, 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Brown, William Fuller (1962). Magnetostatic Principles in Ferromagnetism. North Holland publishing company. p. 12. ASIN B0006AY7F8.

- ^ See magnetic moment[broken anchor] and B. D. Cullity; C. D. Graham (2008). Introduction to Magnetic Materials (2 ed.). Wiley-IEEE. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-471-47741-9.

- ^ E. Richard Cohen; David R. Lide; George L. Trigg (2003). AIP physics desk reference (3 ed.). Birkhäuser. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-387-98973-0.

- ^ Griffiths 1999, p. 438

- ^ a b c Griffiths, David J. (2017). Introduction to Electrodynamics (4th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-35714-2.

- ^ Griffiths 1999, pp. 222–225

- ^ "K. McDonald's Physics Examples - Disk" (PDF). puhep1.princeton.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "K. McDonald's Physics Examples - Railgun" (PDF). puhep1.princeton.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Deissler, R.J. (2008). "Dipole in a magnetic field, work, and quantum spin" (PDF). Physical Review E. 77 (3, pt 2) 036609. Bibcode:2008PhRvE..77c6609D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.77.036609. PMID 18517545. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Griffiths 1999, pp. 266–268

- ^ John Clarke Slater; Nathaniel Herman Frank (1969). Electromagnetism (first published in 1947 ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-486-62263-7.

- ^ Griffiths 1999, p. 332

- ^ a b RJD Tilley (2004). Understanding Solids. Wiley. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-470-85275-0.

- ^ Sōshin Chikazumi; Chad D. Graham (1997). Physics of ferromagnetism (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-19-851776-4.

- ^ Amikam Aharoni (2000). Introduction to the theory of ferromagnetism (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-850808-3.

- ^ M Brian Maple; et al. (2008). "Unconventional superconductivity in novel materials". In K. H. Bennemann; John B. Ketterson (eds.). Superconductivity. Springer. p. 640. ISBN 978-3-540-73252-5.

- ^ Naoum Karchev (2003). "Itinerant ferromagnetism and superconductivity". In Paul S. Lewis; D. Di (CON) Castro (eds.). Superconductivity research at the leading edge. Nova Publishers. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-59033-861-2.

- ^ Lieberherr, Martin (6 July 2010). "The magnetic field lines of a helical coil are not simple loops". American Journal of Physics. 78 (11): 1117–1119. Bibcode:2010AmJPh..78.1117L. doi:10.1119/1.3471233.

- ^ Jackson, John David (1975). Classical electrodynamics (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-43132-9.

- ^ a b Rosser, W. G. V. (1968). Classical Electromagnetism via Relativity. Boston, MA: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-6559-2. ISBN 978-1-4899-6258-4.

- ^ Purcell, Edward (22 September 2011). Electricity and Magnetism. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139005043. ISBN 978-1-107-01360-5.

- ^ C. Doran and A. Lasenby (2003) Geometric Algebra for Physicists, Cambridge University Press, p. 233. ISBN 0-521-71595-4.

- ^ E. J. Konopinski (1978). "What the electromagnetic vector potential describes". Am. J. Phys. 46 (5): 499–502. Bibcode:1978AmJPh..46..499K. doi:10.1119/1.11298.

- ^ Griffiths 1999, p. 422

- ^ Naber, Gregory L. (2012). The Geometry of Minkowski spacetime: an introduction to the mathematics of the special theory of relativity. Springer. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-4419-7837-0. OCLC 804823303.

- ^ For a good qualitative introduction see: Richard Feynman (2006). QED: the strange theory of light and matter. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12575-6.

- ^ Weiss, Nigel (2002). "Dynamos in planets, stars and galaxies". Astronomy and Geophysics. 43 (3): 3.09 – 3.15. Bibcode:2002A&G....43c...9W. doi:10.1046/j.1468-4004.2002.43309.x.

- ^ "What is the Earth's magnetic field?". Geomagnetism Frequently Asked Questions. National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Raymond A. Serway; Chris Vuille; Jerry S. Faughn (2009). College physics (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning. p. 628. ISBN 978-0-495-38693-3.

- ^ Merrill, Ronald T.; McElhinny, Michael W.; McFadden, Phillip L. (1996). "2. The present geomagnetic field: analysis and description from historical observations". The magnetic field of the earth: paleomagnetism, the core, and the deep mantle. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-491246-5.

- ^ Phillips, Tony (29 December 2003). "Earth's Inconstant Magnetic Field". Science@Nasa. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ Boyko, B.A.; Bykov, A.I.; Dolotenko, M.I.; Kolokolchikov, N.P.; Markevtsev, I.M.; Tatsenko, O.M.; Shuvalov, K. (1999). "With record magnetic fields to the 21st Century". Digest of Technical Papers. 12th IEEE International Pulsed Power Conference. (Cat. No.99CH36358). Vol. 2. pp. 746–749. doi:10.1109/PPC.1999.823621. ISBN 0-7803-5498-2. S2CID 42588549.

- ^ a b Daley, Jason. "Watch the Strongest Indoor Magnetic Field Blast Doors of Tokyo Lab Wide Open". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Tuchin, Kirill (2013). "Particle production in strong electromagnetic fields in relativistic heavy-ion collisions". Adv. High Energy Phys. 2013 490495. arXiv:1301.0099. Bibcode:2013arXiv1301.0099T. doi:10.1155/2013/490495. S2CID 4877952.

- ^ Bzdak, Adam; Skokov, Vladimir (29 March 2012). "Event-by-event fluctuations of magnetic and electric fields in heavy ion collisions". Physics Letters B. 710 (1): 171–174. arXiv:1111.1949. Bibcode:2012PhLB..710..171B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.02.065. S2CID 118462584.

- ^ Kouveliotou, C.; Duncan, R. C.; Thompson, C. (February 2003). "Magnetars Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine". Scientific American; Page 36.

- ^ Chapman, Allan (2007). "Peregrinus, Petrus (Flourished 1269)". Encyclopedia of Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 808–809. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4423-6_261. ISBN 978-1-4020-3992-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Whittaker, E. T. (1910). A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-26126-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Williams, L. Pearce (1974). "Oersted, Hans Christian". In Gillespie, C. C. (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 185.

- ^ Blundell, Stephen J. (2012). Magnetism: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-19-163372-0.

- ^ a b Tricker, R. A. R. (1965). Early electrodynamics. Oxford: Pergamon. p. 23.

- ^ Erlichson, Herman (1998). "The experiments of Biot and Savart concerning the force exerted by a current on a magnetic needle". American Journal of Physics. 66 (5): 389. Bibcode:1998AmJPh..66..385E. doi:10.1119/1.18878.

- ^ Frankel, Eugene (1972). Jean-Baptiste Biot: The career of a physicist in nineteenth-century France. Princeton University: Doctoral dissertation. p. 334.

- ^ Lord Kelvin of Largs. physik.uni-augsburg.de. 26 June 1824

- ^ Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003) The Worldwide History of Telecommunications. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-20505-2. p. 202

- ^ "The most important Experiments – The most important Experiments and their Publication between 1886 and 1889". Fraunhofer Heinrich Hertz Institute. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930. JHU Press. March 1993. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8018-4614-4.

- ^ Thomas Parke Hughes, Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930, pp. 115–118

- ^ Ltd, Nmsi Trading; Smithsonian Institution (1998). Robert Bud, Instruments of Science: An Historical Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8153-1561-2. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ U.S. patent 381,968

- ^ Porter, H. F. J.; Prout, Henry G. (January 1924). "A Life of George Westinghouse". The American Historical Review. 29 (2): 129. doi:10.2307/1838546. hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t15m6rz0r. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1838546.

- ^ "Galileo Ferraris (March 1888) Rotazioni elettrodinamiche prodotte per mezzo di correnti alternate (Electrodynamic rotations by means of alternating currents), memory read at Accademia delle Scienze, Torino, in Opere di Galileo Ferraris, Hoepli, Milano, 1902 vol I pages 333 to 348" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Jiles, David (1994). Introduction to Electronic Properties of Materials (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-49580-9.

- Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Electricity, Magnetism, Light, and Elementary Modern Physics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-0810-0. OCLC 51095685.

External links

[edit] Media related to Magnetic fields at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Magnetic fields at Wikimedia Commons- Crowell, B., "Electromagnetism Archived 30 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine".

- Nave, R., "Magnetic Field". HyperPhysics.

- "Magnetism", The Magnetic Field (archived 9 July 2006). theory.uwinnipeg.ca.

- Hoadley, Rick, "What do magnetic fields look like Archived 19 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine?" 17 July 2005.

Magnetic field

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Properties

A magnetic field is a region of space in which magnetic forces are detectable and can influence the motion of moving electric charges, electric currents, or magnetic materials. It arises from the motion of electric charges, such as those in currents, or from the intrinsic magnetic moments of particles, like the spin and orbital angular momentum of electrons in atoms. Unlike electric fields, which can originate from stationary charges, magnetic fields require relative motion or inherent magnetic properties to manifest.[4] The concept of a magnetic field as a "field" permeating space was pioneered by Michael Faraday in the 1830s, who introduced the idea of "lines of force" to describe how magnetic influences extend beyond the physical boundaries of a magnet or current-carrying wire. Faraday visualized these lines as continuous curves that indicate the direction and relative strength of the magnetic influence, emerging from the north pole of a magnet and entering the south pole, forming closed loops in the absence of magnetic monopoles. This qualitative framework laid the groundwork for later mathematical formulations of electromagnetism.[5] As a vector field, a magnetic field has both magnitude and direction at every point in space; the direction is conventionally defined such that the north pole of a compass needle aligns with the field lines, pointing from north to south outside a bar magnet, or follows the right-hand rule for fields produced by currents—curling the fingers in the direction of current flow with the thumb pointing along the wire yields the field direction encircling the wire. Magnetic fields obey the superposition principle, meaning the total field at any point is the vector sum of the fields produced by individual sources, allowing complex configurations to be analyzed by combining simpler contributions. For point-like sources, such as small current elements in vacuum, the field strength follows an inverse square law, decreasing proportionally to 1/r² with distance r from the source.[6][7] A key distinction from electric fields is that magnetic fields exert no net work on isolated charged particles, as the magnetic force is always perpendicular to the particle's velocity, altering only the direction of motion while leaving the speed unchanged. This perpendicularity ensures that the kinetic energy of the charge remains constant, in contrast to electric fields, which can accelerate charges along the field direction and perform work.[8]B and H Fields