Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Imperial Count

View on WikipediaImperial Count (German: Reichsgraf, pronounced [ˈʁaɪ̯çsˌɡʁaːf]) was a title in the Holy Roman Empire. During the medieval era, it was used exclusively to designate the holder of an imperial county, that is, a fief held directly (immediately) from the emperor, rather than from a prince who was a vassal of the emperor or of another sovereign, such as a duke or prince-elector.[1] These imperial counts sat on one of the four "benches" of Counts, whereat each exercised a fractional vote in the Imperial Diet until 1806. Imperial counts rank above counts elevated by lesser sovereigns.

In the post–Middle Ages era, anyone granted the title of Count by the emperor in his specific capacity as ruler of the Holy Roman Empire (rather than, e.g. as ruler of Austria, Bohemia, Hungary, the Spanish Netherlands, etc.) became, ipso facto, an "Imperial Count" (Reichsgraf), whether he reigned over an immediate county or not.

Origins

[edit]In the Merovingian and Franconian Empire, a Graf ("Count") was an official who exercised the royal prerogatives in an administrative district (Gau or "county").[1] A lord designated to represent the king or emperor in a county requiring higher authority than delegated to the typical count acquired a title which indicated that distinction: a border land was held by a margrave, a fortress by a burgrave, an imperial palace or royal estate by a count palatine, a large territory by a landgrave.[1] Originally the counts were ministeriales, appointed administrators, but under the Ottonian emperors, they came to constitute a class, whose land management on behalf of the ruling princes favoured their evolution to a status above not only peasants and burghers, but above landless knights and the landed gentry. Their roles within the feudal system tended to become hereditary and were gradually integrated with those of the ruling nobility by the close of the medieval era.

The possessor of a county within or subject to the Holy Roman Empire might owe feudal allegiance to another noble, theoretically of any rank, who might himself be a vassal of another lord or of the Holy Roman Emperor; or the count might have no other suzerain than the Holy Roman Emperor himself, in which case he was deemed to hold directly or "immediately" (reichsunmittelbar) of the emperor.[1] Nobles who inherited, purchased, were granted or successfully seized such counties, or were able to eliminate any obligation of vassalage to an intermediate suzerain (for instance, by the purchase of his feudal rights from a liege lord), were those on whom the emperor came to rely directly to raise and supply the revenues and soldiers, from their own vassals and manors, which enabled him to govern and protect the empire. Thus their Imperial immediacy tended to secure for them substantial independence within their own territories from the emperor's authority. Gradually they came also to be recognised as counselors entitled to be summoned to his Imperial Diets.

A parallel process occurred among other authorities and strata in the realm, both secular and ecclesiastical. While commoners and the lowest levels of nobles remained subject to the authority of a lord, baron or count, some knights and lords (Reichsfreiherren) avoided owing fealty to any but the emperor yet lacked sufficient importance to obtain consistent admission to the Diet. The most powerful nobles and bishops (Electors) secured the exclusive privilege of voting to choose a Holy Roman Emperor, from among their own number or other rulers, whenever a vacancy occurred.[1] Those just below them in status were recognised as Imperial princes (Reichsfürsten) who, through the hereditary vote each wielded in the Diet's College of Princes, served as members of a loose legislature (cf. peerage) of the Empire.[1]

Power and political role

[edit]As the Empire emerged from the medieval era, immediate counts were definitively excluded from possessing the individual seat and vote (Virilstimme) in the Diet that belonged to electors and princes. In order, however, to further their political interests more effectively and to preserve their independence, the imperial counts organized regional associations and held Grafentage ("countly councils"). In the Imperial Diet, starting in the 16th century, and consistently from the Perpetual Diet (1663–1806), the imperial counts were grouped into "imperial comital associations" known as Grafenbänke. Early in the 16th century, such associations were formed in Wetterau and Swabia. The Franconian association was created in 1640, the Westphalian association in 1653.

They participated with the emperor, electors and princes in ruling the Empire by virtue of being entitled to a seat on one of the Counts' benches (Grafenbank) in the Diet. Each "bench" was entitled to exercise one collective vote (Kuriatstimme) in the Diet and each comital family was allowed to cast one fractional vote toward a bench's vote: A majority of fractional votes determined how that bench's vote would be cast on any issue before the Diet. Four benches were recognised (membership in each being determined by which quadrant of the Empire a count's fief lay within). By being seated and allowed to cast a shared vote on a Count's bench an imperial count obtained, the "seat and vote" within the Imperial Diet which, combined with Imperial immediacy, made of his chief land holding an Imperial estate (Reichsstand) and conferred upon him and his family the status of Landeshoheit, i.e. the semi-sovereignty which distinguished Germany and Austria's high nobility (the Hochadel) from the lower nobility (Niederadel), who had no representation in the Diet and usually answered to an over-lord.

Thus the reichsständische imperial counts pegged their interests and status to those of the imperial princes. In 1521 there were 144 imperial counts; by 1792 only 99 were left. The decrease reflected elevations to higher title, extinction of the male line, and purchase or annexation (outright or by the subordination known as mediatisation) by more powerful imperial princes.

In 1792 there were four associations (benches) of counties contributing the votes of 99 families to the Diet's Reichsfürstenrat:

- the Lower Rhenish-Westphalian Association of Imperial Counts, with 33 members

- the Wetterau Association of Imperial Counts, with 25 members

- the Swabian Association of Imperial Counts, with 24 members

- the Franconian Association of Imperial Counts, with 17 members

By the Treaty of Lunéville of 1800, princely domains west of the Rhine River were annexed to France, including imperial counts. In the Final Recess of the Imperial Delegation of 1803, those deemed to have resisted the French were compensated with secularized Church lands and free cities. Some of the counts, such as Aspremont-Lynden, were generously compensated. Others, such as Leyen, were denied compensation due to failure to resist the French.

By 1806, Napoleon's re-organisation of the continental map squeezed not only all imperial counts but most princes out of existence as quasi-independent entities by the time of the Holy Roman Empire.[1] Each was annexed by its largest German neighbor, although many were swapped by one sovereign to another as they sought to shape more cohesive borders or lucrative markets. In 1815 the Congress of Vienna sought to turn back the clock on the French Revolution's politics, but not on the winnowing of Germany's ruling dynasties and myriad maps. The imperial counts and princes were compensated for the loss of their rights as rulers with largely symbolic privileges, gradually eroded but not extinguished until 1918, including Ebenbürtigkeit; the right to inter-marry with Germany's (and, by extension, Europe's) still reigning dynasties,[1] a prerogative most reichsunmittelbar families had enjoyed prior to mediatisation. A few counties had been elevated to principalities by Napoleon. Most of these were also mediatised by the Congress of Vienna. A few of their dynasties held on to their sovereignty until 1918: Lippe, Reuß, Schwarzburg and Waldeck-Pyrmont.

Status of Imperial count

[edit]

Those counts who received their title by letters patent from the emperor or an Imperial vicar were recognized within the subsequent German Empire as retaining their titles and rank above counts elevated by lesser sovereigns, even if their family had never held imperial immediacy within the Empire. A comital or other title granted by a German sovereign conferred, in principle, rank only in that sovereign's realm,[1] although usually recognised as a courtesy title elsewhere. Titles granted by Habsburg rulers in their capacity as Kings of Hungary, Archdukes or Emperors of Austria were not thereby Reichsgrafen, nor ranked with comparable precedence even post-1806.

Titular imperial counts usually had no role in the ruling of the Empire, although there were exceptions. Sometimes, when a prince wished to marry a lady of lower rank and have her share his title, the Emperor might elevate her to Imperial countess or even princess (often over the objections of his other family members), but this conferred upon her neither the same title nor rank borne by dynasts, nor did it, ipso facto, prevent the marriage from being morganatic.

References and notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pine, L. G. (1992). Titles: How the King became His Majesty. New York: Barnes & Noble. pp. 49, 67–69, 74–75, 84–85, 108–112. ISBN 978-1-56619-085-5.

Imperial Count

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Terminology and Etymology

The title Imperial Count, rendered in German as Reichsgraf, designated a nobleman in the Holy Roman Empire whose comital rank and associated territorial rights were granted or confirmed directly by the emperor, implying immediate feudal allegiance to the imperial crown rather than to an intermediate territorial prince.[5] This terminology underscored the holder's status within the empire's complex hierarchy of estates, where Reichsgrafen possessed privileges such as representation in the Imperial Diet, distinguishing them from non-immediate counts (Grafen) whose authority was mediated through higher lords.[6] The term Graf derives from the Late Latin comes, originally signifying a "companion" or high-ranking associate of the Roman emperor, a role that evolved under the Frankish kingdoms into a local administrator with military, judicial, and fiscal responsibilities over a designated territory known as a comitatus or county.[7] In Germanic languages, comes was adapted as graf or greve, retaining connotations of companionship in governance while adapting to feudal structures where counts served as deputies enforcing royal authority. The prefix Reichs-, meaning "of the empire" or "imperial," was appended to denote direct derivation from the emperor's grant, a practice formalized amid the empire's medieval institutional developments to clarify lines of sovereignty amid fragmented vassalage.[5]Core Legal Attributes

Imperial Counts, or Reichsgrafen, possessed Reichsunmittelbarkeit, a legal status denoting direct feudal subordination to the Holy Roman Emperor without intermediate lords, established as a core attribute by the 12th century.[8] This immediacy applied to both their persons and territories, distinguishing them from territorial counts under princely or ecclesiastical overlords, and ensured their lands were held as imperial fiefs or allods.[9] As Reichsstände (imperial estates), Reichsgrafen enjoyed representation in the Imperial Diet (Reichstag), with collective voting rights allocated to benches of counts (Grafenbänke), formalized after the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.[10] This status granted Landeshoheit (territorial sovereignty), including rights to high and low jurisdiction, police powers, taxation, and minting coinage within their domains, subject to imperial oversight.[11] Hereditary succession of the title and privileges required imperial confirmation via diploma, as exemplified in grants like that to the Schenk von Stauffenberg family in 1785, underscoring the Emperor's role in validating claims to imperial countship. Obligations included military contributions to imperial armies and fiscal aids approved by the Diet, balancing autonomy with fealty to the crown.[12] Such attributes positioned Reichsgrafen hierarchically below princes but above non-immediate nobility, with legal protections against mediatization until the Empire's dissolution in 1806.[13]Historical Origins and Evolution

Early Medieval Foundations

The comital office emerged in the Frankish kingdoms as a key instrument of royal governance, with counts (comites) appointed to administer local districts known as pagi or gau, handling judicial proceedings, tax collection, and military mobilization. Under the Merovingian dynasty from the 5th to 8th centuries, these officials were selected from the nobility to represent the king locally, though their roles often blended royal delegation with personal influence, as seen in early attestations of counts resolving disputes and leading levies.[14] This system drew from late Roman administrative precedents but adapted to decentralized Frankish power structures, where counts enforced royal edicts amid fragmented authority.[15] The Carolingian rulers, beginning with Pippin III (r. 751–768) and intensified under Charlemagne (r. 768–814), reformed the comital institution into a more standardized apparatus of imperial control, appointing counts as itinerant missi dominici to inspect provinces, promulgate capitularies, and suppress rebellion. These positions remained largely non-hereditary, with frequent rotations—such as the reassignment of officials like Gérard of Paris—to prevent the consolidation of autonomous power bases, ensuring counts derived their authority and fiscal benefices (res de comitatu) directly from the crown.[14] Louis the Pious (r. 814–840) continued this oversight through charters that treated comital jurisdictions as recoverable royal assets, exemplified by Lothar I's grants emphasizing revocability.[16] In East Francia, following the 843 Treaty of Verdun's partition of the Carolingian Empire, the office persisted under Louis the German (r. 843–876), where counts like Matfried II managed territories amid Saxon integration and Viking threats, gradually acquiring hereditary traits by the late 9th century. The Ottonian kings (919–1024), from Henry I to Henry II, upheld royal dominance over comital benefices—demonstrated in Otto I's (r. 936–973) reassignments and Henry II's charters (e.g., DH II nr. 142)—yet permitted familial succession in practice, countering narratives of wholesale privatization and establishing the precedent for direct imperial immediacy. This evolution transformed appointive royal agents into foundational estates of the Holy Roman Empire, where counts holding unmediated counties anticipated the Reichsgraf's legal autonomy from intermediate lords.[14][16]Development in the High and Late Middle Ages

During the High Middle Ages, the office of count in the Holy Roman Empire transitioned from appointed administrative roles under the Ottonian and Salian kings to hereditary territorial lordships, with many achieving imperial immediacy by the 11th century through allodial holdings or direct imperial enfeoffments that bypassed intermediate princes.[17] This shift was accelerated by the Investiture Controversy (1075–1122), which weakened central royal authority and enabled counts to defend their jurisdictions against both episcopal and ducal encroachments, consolidating local power through fortified residences and private retinues. By the late 11th century, countships were routinely divisible among heirs and held by minors or women under guardianship, underscoring their proprietary character over official functions.[17] Under the Hohenstaufen dynasty, particularly Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1155–1190), efforts to revitalize comital administration as royal delegates clashed with the entrenched autonomy of hereditary counts, many of whom retained immediacy as "free lords" (liberi domini) rather than subordinates to rising territorial princes.[17] The distinction between ordinary counts (ministeriales or vassals of princes) and Reichsgrafen—those holding counties immediately from the emperor—solidified, with the latter exercising proto-sovereign rights like high justice and coinage in fragmented enclaves. Some counts adopted elevated titles such as landgrave, absorbing ducal military prerogatives amid the empire's decentralization.[17] In the Late Middle Ages, the Great Interregnum (1250–1273) further fragmented authority, prompting emperors like Rudolf I of Habsburg (r. 1273–1291) to grant or confirm immediacy to counts in exchange for electoral support and military aid, swelling their numbers but exposing smaller lineages to absorption by principalities.[18] By the 14th century, Reichsgrafen formed collegiate bodies in embryonic imperial diets, voting collectively in benches (Grafenbänke) with limited influence—one vote per group—reflecting their intermediate status between knights and princes, though territorial sovereignty (Landeshoheit) eroded for many under princely pressures.[17] This period saw alliances among counts, such as the Swabian League of Imperial Counts in the 13th century, to preserve immediacy against Habsburg expansion.[19]Institutionalization through Imperial Reforms

The Reichsreform initiated at the Diet of Worms in 1495 under Emperor Maximilian I laid foundational institutional mechanisms that reinforced the status of Imperial Counts as immediate estates. This reform established the Imperial Chamber Court (Reichskammergericht), a central judicial institution tasked with resolving disputes involving imperial immediacy, thereby providing legal protection for the territorial sovereignty of counties held directly from the Emperor.[20] The court's operations, funded initially through the Common Penny tax approved in 1495, extended to cases where the immediacy of a count's holdings was contested, solidifying their position against encroachments by intermediate lords.[21] Further institutionalization occurred through the creation of the Imperial Circles (Reichskreise) between 1500 and 1512, which organized the Empire into ten districts for administrative, fiscal, and military purposes. Imperial Counts participated in circle diets (Kreistage) as members of the regional estates, contributing to local execution of imperial policies such as peacekeeping and tax collection, while maintaining their exemption from mediate overlordship.[22] This structure enhanced the practical autonomy of their counties, aligning with the reform's aim to balance imperial authority against princely fragmentation without centralizing power excessively. In the Reichstag, the representation of Imperial Counts evolved into a formalized system of four regional colleges (Grafenbänke)—Swabian, Franconian, Wetterau, and Lower Rhenish-Westphalian—each allocated a single curiat vote in the Council of Princes. These collective votes, first structured in the early 16th century amid ongoing reform efforts, allowed groups of counts to deliberate internally before casting a unified voice on imperial matters.[23] The arrangement was confirmed and perpetuated by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which preserved the estates' privileges, and the establishment of the Perpetual Diet in Regensburg in 1663, ensuring consistent participation until the Empire's dissolution.[24] This collegiate framework distinguished Imperial Counts from mediate nobility, embedding their influence within the Empire's constitutional order despite their smaller territorial scale compared to principalities.Powers, Rights, and Duties

Administrative and Judicial Authority

Imperial Counts, as holders of territories with imperial immediacy, exercised Landeshoheit—a form of territorial sovereignty that encompassed broad administrative and judicial powers over their domains, independent of intermediate overlords. This status allowed them to govern their lands as semi-sovereign entities, managing local affairs while remaining directly accountable to the Holy Roman Emperor.[25] In judicial matters, Imperial Counts held comprehensive authority, including the right to establish and preside over courts exercising both low and high justice (Niedergericht and Hochgericht, or Blutgerichtsbarkeit). This permitted them to adjudicate civil disputes, criminal cases, and impose severe punishments such as execution or mutilation, subject only to overarching imperial law and potential appeals to the Imperial Chamber Court (Reichskammergericht). Such powers derived from the devolution of royal prerogatives to immediate vassals, enabling counts to maintain order and enforce feudal obligations within their counties without interference from regional princes.[26] Administratively, they wielded control over taxation, tolls, markets, and infrastructure development, including the maintenance of roads, bridges, and fortifications. Counts could levy direct and indirect taxes on subjects, regulate trade, and organize local police and militia forces to preserve public security and economic stability. These rights often extended to regalian privileges like mining oversight and limited coinage, reinforcing their autonomy in fiscal policy and resource management. However, this authority was tempered by duties to contribute to imperial defense and adhere to decisions of the Imperial Diet, where counts collectively held voting benches.[27] ![Reichsgrafenstands-Diplom granting authority][float-right] The scope of these powers varied by specific imperial grants and historical circumstance; for instance, during the 16th and 17th centuries, many counts consolidated Landeshoheit amid the Empire's decentralization, but faced challenges from encroaching princely territories or imperial reforms like the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803, which eroded smaller estates' independence.Military and Fiscal Obligations

Imperial Counts, as immediate members of the Reichsstände, were required to furnish military aid (auxilium) to the Emperor, entailing the provision of armed forces for the Reichsheer during imperial campaigns. These obligations were codified in the Reichsmatrikel, a register enumerating each estate's quota of cavalry, infantry, and sometimes artillery, which could be fulfilled in kind or commuted to cash equivalents for hiring mercenaries.[28] The quotas reflected territorial size and resources; smaller counties typically supplied modest contingents, such as one to several riders or foot soldiers, as seen in the 1521 Matrikel established at the Diet of Worms, which set the baseline "Simplum" at 4,202 cavalry and 20,000 infantry across all estates.[29] In practice, after the 1555 Peace of Augsburg and especially post-1648 Peace of Westphalia, military execution shifted partly to the Reichskreise, where counts contributed to circle-specific contingents, though direct imperial calls persisted for major threats like Ottoman incursions.[30] Fiscal duties complemented military service, with Imperial Counts assessed for extraordinary imperial taxes (Reichshilfen) to fund common defense, diplomacy, and court expenses. Contributions were often calibrated in Römermonate, a unit derived from the 1521 estimate of one month's army maintenance costs—approximately 128,000 Rhenish guilders for 4,000 cavalry (at 12 guilders each) and 20,000 infantry (at 4 guilders each).[31] Individual counties' shares varied by the Matrikel; prominent examples include fractions like 1/8 or 1/32 of a Römermonat for lesser houses, levied for specific needs such as the Reichstürkenhilfe against Ottoman expansion.[29] These taxes required Diet approval, and counts, voting collectively in their benches (e.g., the Wetterau or Swabian Bank), frequently negotiated or resisted impositions, reflecting the Empire's consensual fiscal structure over absolutist extraction.[28] Upon succession or imperial investiture, counts also owed a Relief—a one-time payment equivalent to a portion of annual revenues—as feudal acknowledgment of immediacy.[28]Representation in Imperial Institutions

Imperial counts with immediate fiefs possessed status as Reichsstände (imperial estates), granting them representation in the Imperial Diet (Reichstag), the primary deliberative body of the Holy Roman Empire.[24] Within the Diet's structure, they were integrated into the Council of Princes (Fürstenrat), specifically the secular bench (weltlicher Bank), alongside princes and prelates.[32] Their participation was channeled through the College of Counts (Reichsgrafenkollegium), subdivided into four regional benches: the Swabian (Schwäbische), Franconian (Fränkische), Wetterau, and Rhineland-Westphalian (Niederrheinisch-Westfälische) benches.[24] Each bench deliberated internally among its members—typically dozens of count families per group—and cast a single collective vote (Kuriatsstimme) in the secular bench, totaling four votes for all counts combined by the late 18th century.[24] A limited number of prominent count houses secured individual virilist votes (Virilstimmen), independent of their bench's collective process, often through imperial grants or long-standing privilege; examples include families like the Counts of Königsegg and Stadion in the Swabian bench.[28] These virilist seats, numbering around four in total across the benches, elevated select lines closer to princely influence, though most counts relied on bench consensus, which required coordination among territorial lords of varying wealth and extent.[24] After the Diet became perpetual in Regensburg on January 23, 1663, count representatives attended sessions there, debating imperial taxes, wars, and reforms until the Empire's dissolution in 1806.[33] Beyond the Reichstag, imperial counts held seats in the assemblies of the ten Imperial Circles (Reichskreise), established by the 1512 Imperial Reform to manage regional defense, taxation, and execution of imperial edicts.[9] In circle diets (Kreistage), counts voted alongside princes, cities, and prelates, often grouped by estate, influencing local contributions to the Heerban (imperial levy) and Gemeiner Pfennig (common penny tax); for instance, Swabian counts dominated proceedings in the Swabian Circle.[10] This dual representation ensured counts' input on both empire-wide policy and Kreis-level enforcement, though their fragmented holdings limited dominance compared to larger princes.[9] Participation demanded fiscal and military commitments, reinforcing their obligations as immediate vassals.[28]Distinctions and Hierarchical Position

Differentiation from Mediatized Nobles

Imperial Counts, or Reichsgrafen, possessed Reichsunmittelbarkeit (imperial immediacy), denoting direct feudal vassalage to the Holy Roman Emperor without intermediate lords, which conferred territorial sovereignty, including rights to administer justice, levy taxes, and maintain military forces within their counties.[34] This status entitled them to collective representation in the Imperial Diet through the Grafenkollegium (College of Counts), subdivided into benches such as the Swabian, Franconian, and Wetterau groups, where they exercised influence over imperial policy until the Empire's dissolution in 1806.[34] In contrast, mediatized nobles emerged primarily from the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803 and subsequent Napoleonic rearrangements (1806–1815), whereby approximately 72 imperial estates, including many counties held by Reichsgrafen, were absorbed into larger sovereign territories like those of Bavaria, Württemberg, or Prussia, stripping them of immediacy and subordinating them to mediate overlordship under new rulers.[35] Former Imperial Counts thus transitioned to Standesherren (lords of the estate), retaining personal titles, private landholdings, and limited feudal privileges—such as lower judicial authority, hunting rights, and exemptions from certain confiscations—but forfeiting public sovereignty, direct imperial ties, and Diet participation.[35] The German Confederation's Federal Act of 1815 formalized this distinction by granting mediatized families elevated protocol rank, including the style Erlaucht (Illustrious) for counts from 1829 onward, positioning them above non-immediate nobility yet below surviving sovereign houses, without restoring pre-mediatization autonomies.[34][35] Examples include the Fugger family, whose counties were mediatized to Bavaria in 1806, preserving comital titles and estates but under Bavarian suzerainty, underscoring the shift from active imperial estate to privileged, non-sovereign nobility.[35] This evolution highlighted the erosion of Reichsgrafen independence amid centralization, differentiating their original constitutional role from the compensatory honors afforded post-1806.[35]Comparison with Higher Imperial Estates

Imperial Counts (Reichsgrafen) held a subordinate position within the hierarchy of imperial estates, ranking below princes (Reichsfürsten), dukes (Herzöge), margraves (Markgrafen), and other higher territorial lords who exercised standesherrliche sovereignty over extensive domains. While both categories enjoyed imperial immediacy—direct feudal allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor without intermediary overlords—princes commanded larger, more consolidated territories often encompassing multiple counties or districts, enabling greater administrative autonomy and military capacity.[6] Counts, by contrast, typically governed fragmented or smaller holdings, limiting their influence relative to princely houses that could mobilize thousands of subjects and resources.[9] In terms of privileges, higher estates wielded broader regalia rights, including exclusive authority over coin minting, mining, toll collection, and high ecclesiastical patronage in their lands, which princes leveraged to sustain independent courts and fortifications. Imperial Counts possessed analogous but scaled-down rights, such as territorial justice and tax levies within their counties, yet these were often contested or overshadowed by neighboring princes' superior claims to ius eminens (eminent domain). For example, princes could veto imperial interventions in their internal affairs more effectively, whereas counts frequently negotiated alliances with higher estates to safeguard their status against mediatization threats.[36] This disparity stemmed from the Empire's decentralized structure, where princely lineages, rooted in Carolingian-era duchies, accumulated hereditary precedence formalized by the 1356 Golden Bull and subsequent reforms.[37] Representation in imperial institutions further underscored the hierarchy: princes dominated the College of Princes in the Imperial Diet (Reichstag), securing individual or house-based votes that amplified their legislative sway, as seen in the post-1648 Westphalian order where they influenced foreign policy and ecclesiastical appointments. Counts, aggregated into separate benches (e.g., Swabian, Franconian, and Rhenish), shared a limited number of virile votes—often four per bench—diluting their collective voice and requiring intra-estate coordination.[9] Elevation from count to princely status, as with the Counts of Cilli in 1436 via imperial diploma, was rare and demanded exceptional land consolidation or service, highlighting the fluidity yet rigidity of this divide.[37] Ultimately, these distinctions reinforced a pyramid of power where higher estates checked imperial authority more robustly, compelling counts to align with princes for survival amid the Empire's confessional and territorial fragmentations.[6]Notable Examples and Case Studies

Prominent Imperial Count Families

The House of Hohenlohe, originating in Franconia and first documented in the 12th century, held imperial immediacy as counts from their elevation by Emperor Frederick III on 13 May 1450 under Count Kraft V, granting them Reichsgraf status and representation in the Imperial Diet.[38][39] Their territories, centered around Uffenheim and later expanding into Swabia, included multiple branches that wielded administrative authority over counties encompassing thousands of subjects and significant feudal revenues by the 16th century.[38] Several lines, such as Hohenlohe-Langenburg, maintained count status until mediatization in 1806, with family members serving in imperial institutions and contributing to regional governance, though later elevations to princely rank in 1744 and 1764 marked the apex of their influence. The House of Stolberg, a Thuringian dynasty first attested in the 13th century, secured Reichsgraf dignity through imperial immediacy over counties in the Harz Mountains and Hesse, with key acquisitions like the Lordship of Schwarza in 1577 bolstering their holdings to approximately 200 square miles by the 17th century.[40] Prominent branches, including Stolberg-Wernigerode and Stolberg-Stolberg, participated in the Franconian and Wetterau colleges of the Imperial Diet, exercising judicial and fiscal rights over mining districts that generated substantial silver and copper output, funding military contributions to imperial campaigns.[40] Counts like Heinrich Ernst (d. 1672) navigated partitions and alliances, preserving family sovereignty until partial mediatization under Napoleon, after which remnants retained noble privileges in Prussia and Württemberg.[40] The Solms family, active in the Wetterau region since the 12th century, exemplified Franconian Imperial Counts with multiple lines holding viril votes in the Reichstag's countly bench, controlling territories yielding an estimated 50,000-100,000 florins annually in taxes by the late 18th century. Their elevation to Reichsgrafen status affirmed immediate feudal ties to the emperor, enabling autonomous courts and minting rights in principalities like Solms-Braunfels. Despite subdivisions into over a dozen branches, core houses like Solms-Hohensolmslich maintained influence through marriages into electoral families, underscoring their role in Hessian politics until dissolution in 1806. The Schenk von Stauffenberg family, Swabian nobles tracing origins to the 14th century as ministerialen (imperial servants), received formal Reichsgraf elevation via diploma in 1785, conferring immediacy over estates in Franconia and Württemberg with judicial prerogatives over several hundred subjects. This late grant under Emperor Joseph II reflected reforms expanding the countly estate, though their holdings remained modest compared to earlier dynasties, focused on agricultural domains rather than expansive counties.Specific Historical Instances of Influence

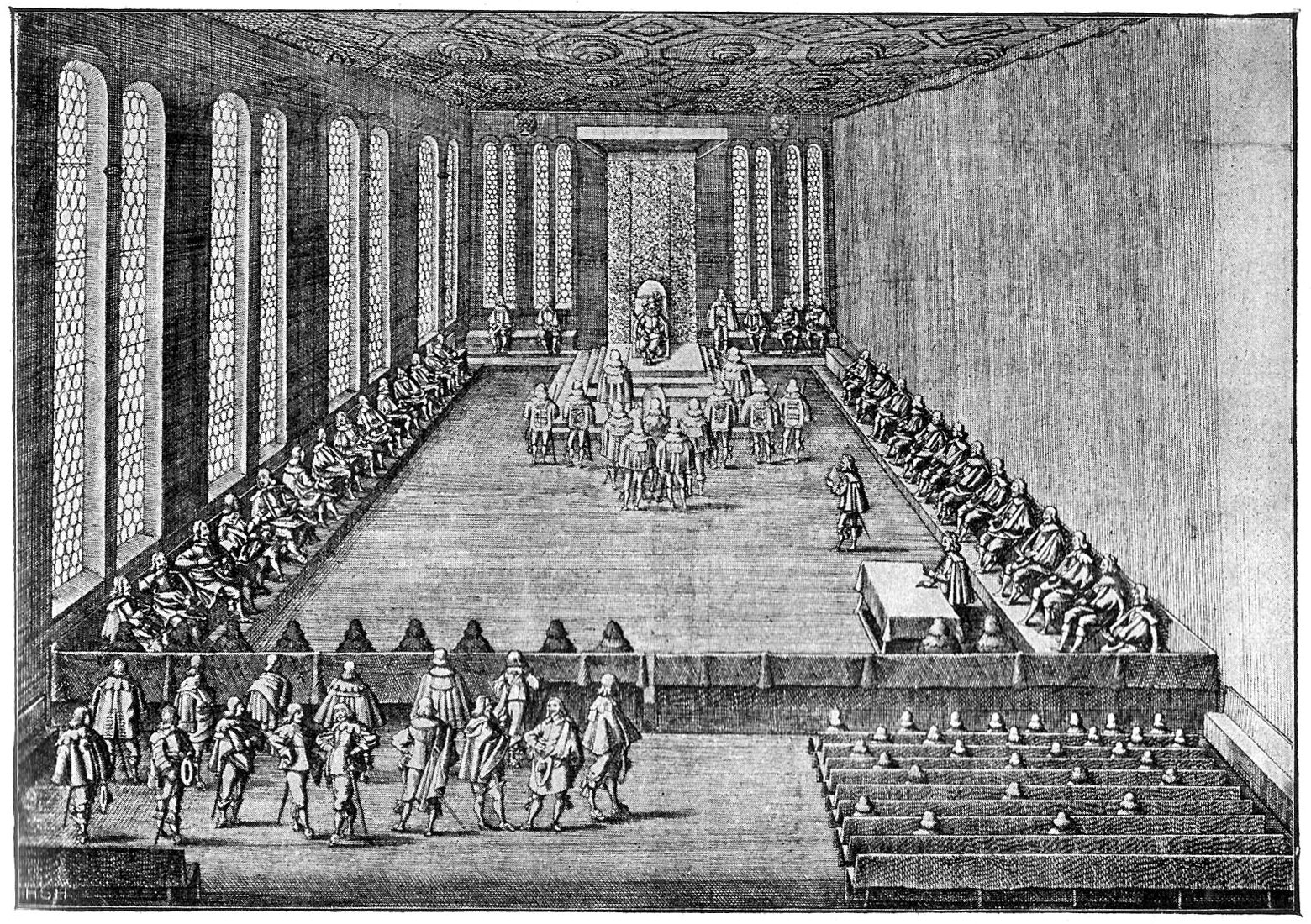

The Fugger family, granted the dignity of Reichsgraf by Emperor Maximilian I in 1511, wielded profound financial influence over Holy Roman Empire politics through banking operations centered in Augsburg. Jakob Fugger II, known as "the Rich," extended massive loans to the Habsburgs, including approximately 543,000 florins disbursed in 1519 to secure the imperial election of Charles V over Francis I of France; these funds were used to bribe key electors, such as providing 100,000 florins to the Elector of Trier and influencing others via direct payments and promises, thereby ensuring Habsburg continuity on the throne and Habsburg dominance in imperial affairs for the subsequent century.[41] ![Session of the Perpetual Imperial Diet in Regensburg, 1640][float-right] In military matters, Friedrich Heinrich, Reichsgraf von Seckendorff, demonstrated the strategic leverage of Imperial Counts during the War of the Polish Succession. Commanding an Imperial army of around 30,000 men in 1735, Seckendorff crossed the Rhine near Philippsburg, defeating French forces under Marshal d'Asfeld in a series of engagements that pressured France toward preliminary peace negotiations and bolstered Austrian Habsburg positions in the Rhineland theater, contributing to the eventual Treaty of Vienna in 1738.[42] During the War of the Austrian Succession, Seckendorff further exemplified martial influence as Bavarian field marshal under Elector Charles Albert (later Emperor Charles VII). In 1742–1743, he coordinated Bavarian-Prussian offensives into Austrian Bohemia, capturing Prague temporarily and challenging Maria Theresa's control, though logistical strains and Franco-Bavarian discord—exemplified by his public quarrels with French Marshal Broglie—tempered gains; his subsequent defection to Austrian service in 1744 aided the reconquest of Bavaria, highlighting the pivotal role of high-ranking Imperial Counts in shifting alliances within the Empire's fragmented warfare.[43] Imperial Counts also shaped deliberative processes in the Perpetual Diet at Regensburg, where their college wielded up to 99 virile votes collectively across subgroups like the Swabian and Franconian benches. In sessions circa 1686–1690, counts' delegations influenced the formulation of the League of Augsburg, advocating for anti-French coalitions that mobilized imperial contingents against Louis XIV's expansions, thereby reinforcing the Empire's defensive posture through collective estate bargaining rather than princely dominance alone.[6]Decline, Mediatization, and Legacy

Factors Leading to Erosion of Status

The erosion of the Imperial Counts' status stemmed primarily from the structural decentralization of the Holy Roman Empire, which empowered larger territorial princes at the expense of smaller immediate estates. By the late 15th century, following the Imperial Reform of 1495 that established the Reichskammergericht and Imperial Circles, princes increasingly exercised de facto sovereignty over their lands, often disregarding imperial oversight and encroaching on adjacent counties through feudal claims, marriages, or coercive diplomacy.[44] This trend intensified after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which codified princes' rights to conduct foreign policy and maintain armies, rendering the Emperor's protective role nominal and leaving counts vulnerable to absorption without effective recourse. Economic and military vulnerabilities exacerbated this process, as many Imperial Counts held fragmented territories averaging under 100 square kilometers, insufficient to sustain independent administrations or defenses against princely expansionism. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) inflicted catastrophic losses, with demographic declines of up to 30–50% in affected regions and massive debts forcing sales of immediacies to solvent princes; for instance, over 100 small estates changed hands between 1620 and 1650 due to wartime fiscal collapse.[45] Lacking the resources for private armies—unlike electors or margraves—counts relied on unreliable imperial execution, which Habsburg emperors, prioritizing dynastic holdings in Austria and Bohemia, often withheld, as evidenced by repeated failures to enforce verdicts against princely violations in the Reichshofrat.[46] Institutional biases within imperial bodies further marginalized counts, whose representation in the Reichstag was limited to collective benches (e.g., the 99 counts divided into four colleges by the 18th century), diluting individual influence compared to the 300+ princely votes. Delays in the overburdened Reichskammergericht, handling thousands of cases annually by 1700 with resolution times exceeding a decade, favored well-resourced litigants and enabled princes to exploit legal limbo for territorial gains.[4] Collectively, these factors—principled in the Empire's federal design favoring scale over equity—eroded the counts' autonomy, transforming many into titular holders within princely enclaves by the late 18th century, even prior to formal mediatization.[47]The Mediatization Process and Dissolution of the HRE

The mediatization of Imperial Counts accelerated through the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss promulgated on 25 February 1803, a decree issued by an imperial deputation under French diplomatic pressure from Napoleon Bonaparte to consolidate territorial holdings and reduce the Empire's fragmented structure.[48] This restructuring incorporated numerous small immediate territories, including those held by Reichsgrafen, into larger secular principalities such as Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden, thereby stripping most Imperial Counts of their Reichsunmittelbarkeit—direct feudal allegiance to the Emperor—and subordinating them to intermediate sovereigns.[35] Approximately 100 sovereign houses, encompassing princes and counts with collective representation in the Imperial Diet's chamber of counts, were affected, shrinking the number of independent German states from over 300 to fewer than 40 by 1806.[35] For Imperial Counts specifically, mediatization entailed the loss of autonomous governance over their enclaves, fiscal independence, and voting rights in imperial institutions like the Reichstag, though some families received compensatory elevations to princely status or retained private lordships (Allodialgut) exempt from full absorption.[49] This process, intertwined with the secularization of ecclesiastical lands, disproportionately impacted lower-tier immediate estates, as larger princes lobbied for annexations to bolster their power amid the Empire's weakening central authority.[48] While not all Reichsgrafen territories were fully mediatized—some baronial or comital houses preserved limited immediacy until later— the 1803 decree marked a causal tipping point, eroding the hierarchical privileges that distinguished Imperial Counts from regional nobility.[4] The dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire culminated on 6 August 1806, when Emperor Francis II abdicated following Napoleon's establishment of the Confederation of the Rhine on 12 July 1806, which unified 16 German states under French protection and rendered the imperial framework obsolete.[50] This event nullified the remaining imperial immediacy for all estates, including unmediatized Imperial Counts, as the Confederation's constitution excluded traditional Reichsstände representation and imposed suzerainty by Napoleon as protector.[51] For Reichsgrafen, the abdication formalized their transition to mediatized status, where former immediate counts became Standesherren (lords of the manor) under the new order, subject to the mediating princes' jurisdictions but often granted residual rights such as immunity from arbitrary seizure of estates and access to higher courts.[35] Post-dissolution recognition of mediatized Imperial Counts occurred at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, where protocols affirmed privileges for around 72 affected princely and comital houses, including equal social precedence with ruling dynasties at court functions and exemption from certain feudal dues, preserving a semblance of their pre-1806 status amid the German Confederation's federal structure.[49] However, these concessions reflected pragmatic diplomacy rather than restoration of sovereignty, as the Empire's end shifted causal power dynamics toward consolidating larger states, ultimately diminishing the Imperial Counts' role in governance to ceremonial and proprietary vestiges.[4] The process thus encapsulated the Empire's terminal fragmentation, driven by external military pressures and internal princely ambitions, leaving Reichsgrafen lineages integrated into modern German aristocracy without independent political agency.Enduring Impacts on German Nobility and Governance

The mediatization of Imperial Counts' territories between 1803 and 1815 reduced their quasi-sovereign status by subordinating them to larger German states, yet preserved key privileges as Standesherren, including exemption from certain taxes, retention of low-level judicial authority over estates, immunity from estate confiscation, and special criminal jurisdiction.[35] These rights, formalized in agreements like the 1815 Final Act of the Vienna Congress, distinguished Reichsgrafen from non-immediate nobles, maintaining their hierarchical precedence over other counts in protocol, intermarriage customs, and social standing across German principalities.[5] By 1815, approximately 112 mediatized houses in total, including numerous former Imperial Counts, benefited from these protections, which shielded their properties—totaling over 6,000 square kilometers—from full absorption and fostered continuity in local manorial governance.[35] In the German Confederation (1815–1866) and subsequent states, mediatized Imperial Counts influenced governance through reserved seats in upper legislative bodies, such as Bavaria's Kammer der Reichsräte established by the 1818 constitution, where Standesherren held collective voting blocs representing their estates.[35] This arrangement embedded aristocratic veto powers over taxation and land reforms, reinforcing federalism's conservative tilt and slowing centralization efforts until the North German Confederation of 1867. Similar provisions in Württemberg and Baden granted former Reichsgrafen sway in state diets, where they advocated for noble exemptions, impacting policies on feudal dues and military obligations until the 1871 German Empire's constitution subordinated such bodies to imperial oversight.[5] The Weimar Constitution of 1919 abolished Standesherren privileges, mandating legal equality and dissolving noble jurisdictions, yet Reichsgraf titles endured as private distinctions without state recognition.[52] This shift ended formal governance roles but perpetuated informal aristocratic networks in diplomacy, military, and industry; for instance, families like the Fugger or Thurn und Taxis leveraged pre-1806 prestige for economic influence into the 20th century. Post-1945, in the Allied occupation zones, remaining symbolic noble privileges were addressed through zone-specific decrees and reinforced by the 1949 Basic Law's equality provisions, but cultural legacies—such as precedence in noble associations—sustained a distinct stratum within German society, indirectly shaping elite political conservatism without legal entailment.[5][53] ![Reichsgrafenstands-Diplom_Schenk_von_Stauffenberg_1785.jpg][center]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Count