Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Key derivation function

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2013) |

In cryptography, a key derivation function (KDF) is a cryptographic algorithm that derives one or more secret keys from a secret value such as a master key, a password, or a passphrase using a pseudorandom function (which typically uses a cryptographic hash function or block cipher).[1][2][3] KDFs can be used to stretch keys into longer keys or to obtain keys of a required format, such as converting a group element that is the result of a Diffie–Hellman key exchange into a symmetric key for use with AES. Keyed cryptographic hash functions are popular examples of pseudorandom functions used for key derivation.[4]

History

[edit]The first[citation needed] deliberately slow (key stretching) password-based key derivation function was called "crypt" (or "crypt(3)" after its man page), and was invented by Robert Morris in 1978. It would encrypt a constant (zero), using the first 8 characters of the user's password as the key, by performing 25 iterations of a modified DES encryption algorithm (in which a 12-bit number read from the real-time computer clock is used to perturb the calculations). The resulting 64-bit number is encoded as 11 printable characters and then stored in the Unix password file.[5] While it was a great advance at the time, increases in processor speeds since the PDP-11 era have made brute-force attacks against crypt feasible, and advances in storage have rendered the 12-bit salt inadequate. The crypt function's design also limits the user password to 8 characters, which limits the keyspace and makes strong passphrases impossible.

Although high throughput is a desirable property in general-purpose hash functions, the opposite is true in password security applications in which defending against brute-force cracking is a primary concern. The growing use of massively-parallel hardware such as GPUs, FPGAs, and even ASICs for brute-force cracking has made the selection of a suitable algorithms even more critical because the good algorithm should enforce a certain amount of computational cost not only on CPUs, but also resist the cost/performance advantages of modern massively-parallel platforms for such tasks. Various algorithms have been designed specifically for this purpose, including bcrypt, scrypt and, more recently, Lyra2 and Argon2 (the latter being the winner of the Password Hashing Competition). The large-scale Ashley Madison data breach in which roughly 36 million passwords hashes were stolen by attackers illustrated the importance of algorithm selection in securing passwords. Although bcrypt was employed to protect the hashes (making large scale brute-force cracking expensive and time-consuming), a significant portion of the accounts in the compromised data also contained a password hash based on the fast, general-purpose, and insecure MD5 algorithm, which made it possible for over 11 million of the passwords to be cracked in a matter of weeks.[6]

In June 2017, The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) issued a new revision of their digital authentication guidelines, NIST SP 800-63B-3,[7]: 5.1.1.2 stating that: "Verifiers SHALL store memorized secrets [i.e. passwords] in a form that is resistant to offline attacks. Memorized secrets SHALL be salted and hashed using a suitable one-way key derivation function. Key derivation functions take a password, a salt, and a cost factor as inputs then generate a password hash. Their purpose is to make each password guessing trial by an attacker who has obtained a password hash file expensive and therefore the cost of a guessing attack high or prohibitive."

Modern password-based key derivation functions, such as PBKDF2,[2] are based on a recognized cryptographic hash, such as SHA-2, use more salt (at least 64 bits and chosen randomly) and a high iteration count. NIST recommends a minimum iteration count of 10,000.[7]: 5.1.1.2 "For especially critical keys, or for very powerful systems or systems where user-perceived performance is not critical, an iteration count of 10,000,000 may be appropriate.” [8]: 5.2

Key derivation

[edit]The original use for a KDF is key derivation, the generation of keys from secret passwords or passphrases. Variations on this theme include:

- In conjunction with non-secret parameters to derive one or more keys from a common secret value (which is sometimes also referred to as "key diversification"). Such use may prevent an attacker who obtains a derived key from learning useful information about either the input secret value or any of the other derived keys. A KDF may also be used to ensure that derived keys have other desirable properties, such as avoiding "weak keys" in some specific encryption systems.

- As components of multiparty key-agreement protocols. Examples of such key derivation functions include KDF1, defined in IEEE Std 1363-2000, and similar functions in ANSI X9.42.

- To derive keys from secret passwords or passphrases (a password-based KDF).

- To derive keys of different length from the ones provided. KDFs designed for this purpose include HKDF and SSKDF. These take an 'info' bit string as an additional optional 'info' parameter, which may be crucial to bind the derived key material to application- and context-specific information.[9]

- Key stretching and key strengthening.

Key stretching and key strengthening

[edit]Key derivation functions are also used in applications to derive keys from secret passwords or passphrases, which typically do not have the desired properties to be used directly as cryptographic keys. In such applications, it is generally recommended that the key derivation function be made deliberately slow so as to frustrate brute-force attack or dictionary attack on the password or passphrase input value.

Such use may be expressed as DK = KDF(key, salt, iterations), where DK is the derived key, KDF is the key derivation function, key is the original key or password, salt is a random number which acts as cryptographic salt, and iterations refers to the number of iterations of a sub-function. The derived key is used instead of the original key or password as the key to the system. The values of the salt and the number of iterations (if it is not fixed) are stored with the hashed password or sent as cleartext (unencrypted) with an encrypted message.[10]

The difficulty of a brute force attack is increased with the number of iterations. A practical limit on the iteration count is the unwillingness of users to tolerate a perceptible delay in logging into a computer or seeing a decrypted message. The use of salt prevents the attackers from precomputing a dictionary of derived keys.[10]

An alternative approach, called key strengthening, extends the key with a random salt, but then (unlike in key stretching) securely deletes the salt.[11] This forces both the attacker and legitimate users to perform a brute-force search for the salt value.[12] Although the paper that introduced key stretching[13] referred to this earlier technique and intentionally chose a different name, the term "key strengthening" is now often (arguably incorrectly) used to refer to key stretching.

Password hashing

[edit]Despite their original use for key derivation, KDFs are possibly better known for their use in password hashing (password verification by hash comparison), as used by the passwd file or shadow password file. Password hash functions should be relatively expensive to calculate in case of brute-force attacks, and KDFs are designed with this characteristic built in.[14] The non-secret parameters are called "salt" in this context.

In 2013 a Password Hashing Competition was announced to choose a new, standard algorithm for password hashing. On 20 July 2015 the competition ended and Argon2 was announced as the final winner. Four other algorithms received special recognition: Catena, Lyra2, Makwa and yescrypt.[15]

As of May 2023, the Open Worldwide Application Security Project (OWASP) recommends the following KDFs for password hashing, listed in order of priority:[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Bezzi, Michele; et al. (2011). "Data privacy". In Camenisch, Jan; et al. (eds.). Privacy and Identity Management for Life. Springer. pp. 185–186. ISBN 9783642203176.

- ^ a b B. Kaliski; A. Rusch (January 2017). K. Moriarty (ed.). PKCS #5: Password-Based Cryptography Specification Version 2.1. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC8018. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 8018. Informational. Obsoletes RFC 2898. Updated by RFC 9579.

- ^ Chen, Lily (October 2009). "NIST SP 800-108: Recommendation for Key Derivation Using Pseudorandom Functions". NIST.

- ^ Zdziarski, Jonathan (2012). Hacking and Securing IOS Applications: Stealing Data, Hijacking Software, and How to Prevent It. O'Reilly Media. pp. 252–253. ISBN 9781449318741.

- ^ Morris, Robert; Thompson, Ken (3 April 1978). "Password Security: A Case History". Bell Laboratories. Archived from the original on 22 March 2003. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ Goodin, Dan (10 September 2015). "Once seen as bulletproof, 11 million+ Ashley Madison passwords already cracked". Ars Technica. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ a b Grassi Paul A. (June 2017). SP 800-63B-3 – Digital Identity Guidelines, Authentication and Lifecycle Management. NIST. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-63b.

- ^ Meltem Sönmez Turan; Elaine Barker; William Burr; Lily Chen (December 2010). SP 800-132 – Recommendation for Password-Based Key Derivation, Part 1: Storage Applications (PDF). NIST. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-132. S2CID 56801929.

- ^ Krawczyk, Hugo; Eronen, Pasi (May 2010). "The 'info' Input to HKDF". datatracker.ietf.org. RFC 5869 (2010)

- ^ a b "Salted Password Hashing – Doing it Right". CrackStation.net. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ Abadi, Martın, T. Mark A. Lomas, and Roger Needham. "Strengthening passwords." Digital System Research Center, Tech. Rep 33 (1997): 1997.

- ^ U. Manber, "A Simple Scheme to Make Passwords Based on One-Way Functions Much Harder to Crack," Computers & Security, v.15, n.2, 1996, pp.171–176.

- ^ Secure Applications of Low-Entropy Keys, J. Kelsey, B. Schneier, C. Hall, and D. Wagner (1997)

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (December 2010). Recommendation for Password-Based Key Derivation (PDF) (Report). Special Publication. Vol. 800–132. NIST.

- ^ "Password Hashing Competition"

- ^ "Password Storage Cheat Sheet". OWASP Cheat Sheet Series. OWASP. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Percival, Colin (May 2009). "Stronger Key Derivation via Sequential Memory-Hard Functions" (PDF). BSDCan'09 Presentation. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- Key Derivation Functions

Key derivation function

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

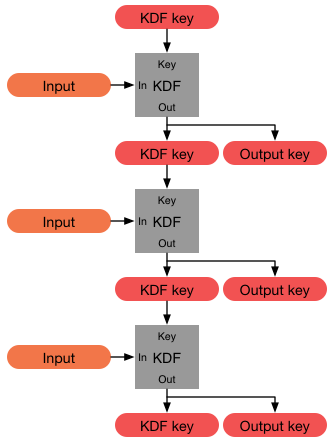

A key derivation function (KDF) is a deterministic algorithm that derives one or more cryptographic keys from an input secret, such as a master key, shared secret, or password, by applying a pseudorandom function (PRF), typically based on a hash function or block cipher, to produce keying material suitable for use in cryptographic algorithms.[2] The process ensures that the output keys are cryptographically strong, even if the input secret has limited entropy or structure.[6] The primary inputs to a KDF include the secret input key material (often denoted as or IKM), an optional salt (a non-secret random value to prevent precomputation attacks), and contextual information (such as a label or info string providing application-specific details).[6] An iteration count may also be specified to apply the PRF multiple times, increasing computational resistance.[7] The output consists of one or more derived keys (DK), typically as a bit string of a specified length , which can be partitioned for multiple uses.[2] In general mathematical form, the operation is represented as: where is the input secret, salt and info are optional parameters, and defines the output length.[2][6] Unlike directly using a secret as a key, which may expose it to risks from low entropy or predictable patterns, a KDF transforms potentially weak or structured inputs into uniformly distributed, high-entropy keys that mimic the properties of randomly generated keys.[2] This transformation is essential for key expansion and management in protocols.[6]Purpose and Benefits

Key derivation functions (KDFs) primarily serve to generate one or more cryptographic keys from a single source of initial keying material, such as a shared secret or master key, enabling secure key management in various protocols.[6] They also expand short or weak inputs, like user passwords, into full-length keys suitable for symmetric encryption algorithms, thereby transforming low-entropy secrets into cryptographically robust outputs.[4] For instance, in password-based scenarios, KDFs produce keys of appropriate length for applications like data encryption, ensuring the derived material meets the security requirements of the target cipher.[7] A key benefit of KDFs is their ability to enhance resistance to brute-force attacks by increasing the computational effort required to derive keys from the input secret, without compromising the underlying secret itself.[7] They promote key uniformity and independence, making derived keys statistically close to random and computationally indistinguishable from one another, even when generated from the same input.[6] Additionally, KDFs format keys to align with specific cryptographic algorithms, such as deriving AES-compatible keys, which streamlines integration in security systems.[3] Passwords often suffer from low entropy and predictability, making them vulnerable to guessing or dictionary attacks, as users tend to choose memorable but common phrases with limited randomness.[7] KDFs address these weaknesses by processing such inputs into secure keys while preserving the original secret's integrity, thus mitigating offline attacks that exploit the input's guessability.[6] In key hierarchies, KDFs facilitate separation of duties by deriving distinct keys for different purposes from a master secret, such as an encryption key and a message authentication code (MAC) key within the same protocol.[3] This approach ensures that compromise of one derived key does not affect others, enhancing overall protocol security through compartmentalized key usage.[2]History

Early Developments

The origins of key derivation functions (KDFs) trace back to early efforts in securing password storage against brute-force attacks. In 1979, Robert Morris and Ken Thompson introduced a deliberately slow password hashing mechanism in their paper "Password Security: A Case History," implemented as the Unixcrypt command. This system used the first eight characters of a user's password as a key for the Data Encryption Standard (DES) algorithm, encrypting a constant 64-bit block of zeros and iterating the process 25 times to produce an 11-character output stored in the password file. By leveraging software-based DES encryption, which was computationally intensive at the time, and adding iterations, this approach increased the time required for password guessing on hardware like the PDP-11/70 from milliseconds to seconds per attempt, serving as an early form of key stretching to derive secure keys from weak passwords.[8]

During the 1990s, the advent of faster cryptographic hash functions influenced the evolution of key derivation techniques, emphasizing the need for computational slowness to counter advancing hardware capabilities. MD5, proposed by Ronald Rivest in 1991, and SHA-1, standardized by NIST in 1995, were increasingly adopted in password-based systems due to their efficiency and collision resistance, often combined with iterations or salts to derive keys from user inputs. These hashes replaced or augmented earlier DES-based methods in variants of Unix crypt implementations, highlighting an early recognition that rapid hashing alone was insufficient against brute-force attacks, as dictionary and exhaustive searches could exploit hardware speedups without deliberate delays. For instance, systems began iterating these functions multiple times to amplify derivation time, building on the 1979 principles to make offline attacks more resource-intensive.

Key milestones in the 1990s underscored the growing application of simple KDFs in protocols. The Kerberos Version 5 protocol, specified in RFC 1510 in 1993, employed a basic string-to-key derivation for user passwords: the password string (with realm and principal appended) was padded to an 8-byte boundary, fan-folded and XORed to form a DES key, parity-corrected, and checked against weak keys via a CBC checksum using DES CBC. This method derived an 8-octet session key for authenticating clients to the Key Distribution Center, prioritizing simplicity for network environments while incorporating basic protections against direct password exposure. By 2000, NIST's initial guidelines on password-based encryption, outlined in PKCS #5 Version 2.0 (RFC 2898), formalized PBKDF2 as a recommended function, applying a pseudorandom function like HMAC-SHA-1 iteratively (with a minimum of 1,000 rounds) alongside a salt to derive keys of variable lengths, addressing limitations of prior ad-hoc methods.[9][7]

This period marked a conceptual shift from relying on inherently fast cryptographic primitives—such as single-pass hashes—for key generation to intentionally incorporating computation delays via iterations and salts, ensuring that derived keys resisted brute-force and dictionary attacks even as computing power grew exponentially. Key stretching, the core technique enabling this, aimed to equate the effort of deriving a key from a password to that of guessing it directly, thereby elevating weak human-memorable inputs to cryptographic strength without requiring perfect secrecy.[8]

Standardization and Evolution

The standardization of key derivation functions (KDFs) began to formalize in the early 2000s, with the publication of RFC 2898 in 2000, which specified PBKDF2 as a password-based KDF using a pseudorandom function like HMAC to apply salt and iterations for key stretching.[10] In 2010, NIST released Special Publication 800-132, providing recommendations for password-based key derivation in storage and communication applications, emphasizing the use of approved pseudorandom functions and minimum iteration counts to enhance security against brute-force attacks.[11] These standards built upon earlier foundational work, such as the Unix crypt function introduced in the 1970s, which first incorporated salting to prevent precomputed dictionary attacks. Post-2000s evolution in KDF design was driven by real-world security incidents and advances in computational hardware, highlighting vulnerabilities in weaker hashing practices. The 2015 Ashley Madison data breach exposed over 36 million weakly protected password hashes, many using outdated or insufficiently iterated methods like bcrypt with programming flaws, underscoring the need for more robust, memory-intensive KDFs to resist GPU-accelerated cracking.[12] This incident accelerated the shift toward memory-hard functions; for instance, scrypt was introduced in 2009 as a KDF designed to require significant RAM, making parallelized attacks on specialized hardware more costly.[13] Further momentum came from the 2013–2015 Password Hashing Competition, where Argon2 emerged as the winner for its balanced resistance to both time- and memory-based attacks through configurable parameters for parallelism, memory, and iterations.[14] Recent updates reflect ongoing refinements to address emerging threats, including hardware advancements and quantum computing risks. In 2015, RFC 5869 defined HKDF, an HMAC-based extract-and-expand KDF tailored for deriving keys from high-entropy sources in protocols like TLS, prioritizing simplicity and provable security properties.[6] OWASP's 2023 Password Storage Cheat Sheet prioritizes Argon2id—a hybrid variant of Argon2 combining data-dependent and independent modes—for new implementations, recommending minimum parameters of 19 MiB memory, 2 iterations, and 1 degree of parallelism to balance security and performance. In the 2023 proposal to revise SP 800-132, NIST plans to incorporate memory-hard functions like Argon2 alongside PBKDF2, with updated guidance on parameters such as iteration counts.[15] Post-2023 developments increasingly explore quantum-safe KDF adaptations, particularly those based on lattice problems, to withstand attacks from quantum algorithms like Grover's that could halve the effective security of symmetric primitives. For example, lattice-based constructions such as those derived from Learning With Errors (LWE) problems—central to NIST's post-quantum standards like ML-KEM—enable key derivation with hardness assumptions resilient to quantum adversaries, though full integration into KDF standards remains in early research stages. In 2024, NIST finalized FIPS 203, 204, and 205, standardizing post-quantum algorithms like ML-KEM, which employ KDFs in hybrid key encapsulation mechanisms to ensure quantum resistance in key derivation processes. These efforts address gaps in prior guidelines, aiming to future-proof KDFs against anticipated quantum threats by 2030.[16][17]Core Principles

Key Stretching

Key stretching is a cryptographic technique employed in key derivation functions to enhance the security of weak inputs, such as low-entropy passwords or passphrases, by deliberately increasing the computational workload required to produce the derived key. This is accomplished through the iterative application of a one-way function, typically a cryptographic hash, which transforms the input into a stronger key by amplifying its resistance to brute-force attacks. The core goal is to make each derivation attempt sufficiently resource-intensive, thereby deterring exhaustive searches that would otherwise exploit the limited entropy of human-chosen secrets.[18] The mathematical foundation of key stretching relies on repeated function evaluations, where the output after iterations is computed as , with denoting sequential applications and concatenation. For iterations, the time complexity scales linearly with , as each step demands a complete execution of the underlying hash function, resulting in a total cost of approximately operations. This linear scaling enables tunable security: practitioners select to achieve a target derivation time, often calibrated to one second on typical hardware, ensuring that even modest increases in attacker resources yield proportionally higher costs. Salt usage serves as a complementary measure to prevent precomputation attacks, though stretching primarily focuses on computational delay.[7] Historically, key stretching emerged as a countermeasure to the accelerating computational power predicted by Moore's Law, which posits that processing capabilities roughly double every 18 to 24 months, thereby halving the effective security of fixed-entropy keys over time. By design, the technique allows for adjustable iteration counts to maintain consistent derivation slowness amid hardware advancements, preserving security margins without requiring key redesign. This adaptability addresses the vulnerability of static protections to exponential growth in attack feasibility.[19] In contrast to plain hashing, which prioritizes rapid computation for efficient data verification or integrity checks in online environments, key stretching intentionally introduces delay during key generation to mitigate offline threats. Plain hashing enables quick lookups for authentication but offers minimal protection against captured data, as attackers can perform rapid trials; stretching, however, targets the derivation phase, ensuring that generating candidate keys from guesses becomes prohibitively slow, thus shifting the economic burden to the adversary.[7]Salt and Iteration Mechanisms

In key derivation functions (KDFs), a salt is a non-secret, randomly generated binary value, typically at least 128 bits in length, that is unique to each derivation instance or user. It serves to prevent precomputed attacks, such as rainbow tables, by ensuring that the same input secret produces distinct outputs across different derivations, thereby defeating dictionary attacks on common passwords and protecting against identical-input vulnerabilities where multiple users share the same secret. Salts are generated using an approved random bit generator and must be stored alongside the derived key or hash, as they are not secret and cannot be reconstructed.[4][7] Iteration mechanisms enhance security by applying a pseudorandom function (PRF) repeatedly an adjustable number of times, often 100,000 or more, to amplify the computational workload required for derivation. The NIST SP 800-132 standard requires a minimum of 1,000 iterations, but current best practices recommend significantly higher values, such as at least 600,000 for PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256, to counter modern attack capabilities using specialized hardware.[20] This count is tunable to balance security needs against performance constraints, such as user-perceived delays, with higher values for critical applications. The sequential application of iterations inherently resists parallel processing, making brute-force and exhaustive search attacks more resource-intensive.[4][7] These mechanisms support key stretching by deliberately prolonging derivation time from low-entropy inputs like passwords. In many constructions, the derived key results from iterating the PRF N times on the concatenation of the secret, salt, and optional context information: where denotes concatenation and is the iteration count.[7][4] Advanced variants include peppers, which are secret, application-wide values added to the input before derivation, stored separately from the database (e.g., in a hardware security module) rather than with individual salts. Unlike salts, peppers are not unique per user and provide an extra barrier against offline attacks if the primary storage is breached, though their compromise necessitates widespread key rotation. Domain separation further refines these by incorporating non-secret context information, such as labels or identifiers, into the 'info' parameter to ensure keys derived for different purposes (e.g., encryption versus authentication) remain cryptographically independent, preventing cross-use vulnerabilities.[20][21][6]Constructions and Algorithms

Hash-Based and HMAC-Based KDFs

Hash-based key derivation functions (KDFs) utilize cryptographic hash functions, such as SHA-256, in iterated chains to transform input keying material into derived keys of desired length. These constructions typically involve repeatedly hashing the input combined with a salt to achieve key stretching, ensuring that even low-entropy sources produce longer, more secure outputs. For example, a basic hash-based KDF might compute the derived key as the concatenation of multiple hash iterations: DK = Hash(salt || IKM) || Hash(Hash(salt || IKM)) || ... for a specified number of rounds. This approach is simple to implement and relies solely on the collision resistance and preimage resistance of the underlying hash function. However, the sequential nature of plain hash iterations in these KDFs makes them particularly vulnerable to parallel attacks, where adversaries can distribute computations across multiple processors or GPUs to accelerate brute-force or dictionary searches. Without the keyed structure of more advanced PRFs, parallelization is straightforward, reducing the effective security margin against hardware-accelerated cracking.[22] To mitigate these issues, HMAC-based KDFs employ the Hash-based Message Authentication Code (HMAC) as a pseudorandom function (PRF), leveraging HMAC's proven security properties for keyed hashing. HMAC constructs a PRF from a hash function H by sandwiching the key and message between nested hashes, providing resistance to length-extension attacks inherent in Merkle-Damgård hashes. This makes HMAC-based designs suitable for deriving keys in both password and general cryptographic contexts.[23] A foundational HMAC-based KDF is PBKDF2, introduced in the PKCS #5 v2.0 standard in 2000 and formalized in RFC 2898. PBKDF2 derives a key DK of length dkLen from a password P, salt S (at least 8 octets), and iteration count c (current recommendations suggest at least 310,000 or higher for HMAC-SHA256, depending on hardware capabilities as of 2024) using a PRF such as HMAC-SHA256 (HMAC-SHA1 is deprecated for new uses). The algorithm proceeds in blocks: for each block i from 1 to l = ceil(dkLen / hLen), compute T_i as the XOR of c PRF values, starting with U_1 = PRF(P, S || INT(i)) and U_k = PRF(P, U_{k-1}) for k = 2 to c; then T_i = U_1 XOR U_2 XOR ... XOR U_c. The final DK is the concatenation T_1 || T_2 || ... || T_l, truncated to dkLen octets. This iteration mechanism, briefly referencing the chaining in U_k computations, enforces computational work to slow down attackers. PBKDF2 supports variable-length outputs up to (2^32 - 1) * hLen and is widely implemented for its balance of security and performance.[10][24] For non-password scenarios, such as deriving keys from Diffie-Hellman exchanges or entropy sources, HKDF provides a more modular HMAC-based alternative, specified in RFC 5869 (2010) following the extract-then-expand paradigm. The extract step first produces a fixed-length pseudorandom key PRK from input keying material IKM and optional salt (defaulting to hLen zeros if omitted):PRK = HMAC-Hash(salt, IKM)

PRK = HMAC-Hash(salt, IKM)

T_i = HMAC-Hash(PRK, T_{i-1} || info || 0x01 || ... || 0xFF (for i in bytes))

T_i = HMAC-Hash(PRK, T_{i-1} || info || 0x01 || ... || 0xFF (for i in bytes))