Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

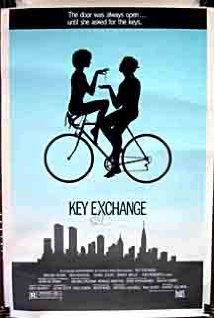

Key Exchange

View on Wikipedia| Key Exchange | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Barnet Kellman |

| Screenplay by | Paul Kurta Kevin Scott |

| Based on | Key Exchange by Kevin Wade |

| Produced by | Paul Kurta Mitchell Maxwell |

| Starring | Brooke Adams Ben Masters Danny Aiello Seth Allen |

| Cinematography | Fred Murphy |

| Edited by | Jill Savitt |

| Music by | Mason Daring |

Production companies | 20th Century Fox M-Square Entertainment, Inc. |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.5 million[1] |

Key Exchange is a 1985 American romantic comedy film directed by Barnet Kellman and starring Brooke Adams as Lisa.[2] The film is based on a play by Kevin Wade.[2] The film was released by 20th Century Fox on August 14, 1985.[3][4][5]

Plot

[edit]A young woman wishes to get her boyfriend to commit to her, yet the most she can manage to do is get him to exchange apartment keys.

Cast

[edit]- Brooke Adams as Lisa

- Ben Masters as Philip

- Danny Aiello as Carabello

- Daniel Stern as Michael

- Seth Allen as Frank

- Kerry Armstrong as The Beauty

- Sandra Beall as Marcy

- Annie Golden as Val

- Peter Brinkerhoff as Willie, The Stage Manager

- Ian Calderon as Lighting Technician

- John Spencer as Record Executive

- Keith Charles as Mr. Simon

- Roger Christiansen as A.D. Switcher

- John Cunningham as Sloane

- Ned Eisenberg as Piero

Production

[edit]The rights to the play were first purchased in November 1981. After negotiations with Mel Damski and Jamie Lee Curtis to direct and star respectively fell through, Barnet Kellman, who had directed the stage production was hired as director while Brooke Adams and Ben Masters who had acted in the stage production reprised their roles. Although Daniel Stern had never starred in Key Exchange, he was familiar with the work as he was slated to appear in the original stage production prior to dropping out in favor of Diner. The film was adapted by producer Paul Kurta and his production assistant, Kevin Scott, after attempts to find a screenwriter proved unsuccessful.[1]

Reception

[edit]In a review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby was positive in his assessment "What sustains Key Exchange is not surprise, but the intelligence of its characters and of the people who made it."[6]

In a negative review for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert wrote, "Key Exchange is about two people who have a relationship but should not, two people who are married but should not be and the ways in which they all arrive at a singularly unconvincing happy ending".[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Key Exchange (1985)". AFI. Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (August 14, 1985). "Key Exchange (1985) SCREEN: 'KEY EXCHANGE,' A COMEDY". The New York Times.

- ^ "Key Exchange". afi.com. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Key Exchange". AllMovie. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Key Exchange". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (August 14, 1985). "SCREEN: 'KEY EXCHANGE,' A COMEDY". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 13, 1985). "Key Exchange". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 19, 2025.