Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

L game

View on Wikipedia

The L game is a simple abstract strategy board game invented by Edward de Bono. It was introduced in his book The Five-Day Course in Thinking (1967).

Description

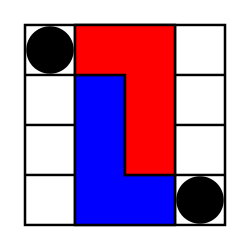

[edit]The L game is a two-player game played on a board of 4×4 squares. Each player has a 3×2 L-shaped tetromino, and there are two 1×1 neutral pieces.

Rules

[edit]On each turn, a player must first move their L piece, and then may optionally move either one of the neutral pieces. The game is won by leaving the opponent unable to move their L piece to a new position.

Pieces may not overlap or cover other pieces, or let the pieces off the board. On moving the L piece, it is picked up and then placed in empty squares anywhere on the board. It may be rotated or even flipped over in doing so; the only rule is that it must end in a different position from the position it started—thus covering at least one square it did not previously cover. To move a neutral piece, a player simply picks it up then places it in an empty square anywhere on the board.

Strategy

[edit]One basic strategy is to use a neutral piece and one's own piece to block a 3×3 square in one corner, and use a neutral piece to prevent the opponent's L piece from swapping to a mirror-image position. Another basic strategy is to move an L piece to block a half of the board, and use the neutral pieces to prevent the opponent's possible alternate positions.

These positions can often be achieved once a neutral piece is left in one of the eight killer spaces on the perimeter of the board. The killer spaces are the spaces on the perimeter, but not in a corner. On the next move, one either makes the previously placed killer a part of one's square, or uses it to block a perimeter position, and makes a square or half-board block with one's own L and a moved neutral piece.

Analysis

[edit]In a game with two perfect players, neither will ever win or lose. The L game is small enough to be completely solvable. There are 2296 different possible valid ways the pieces can be arranged, not counting a rotation or mirror of an arrangement as a new arrangement, and considering the two neutral pieces to be identical. Any arrangement can be reached during the game, with it being any player's turn. Each player has lost in 15 of these arrangements, if it is that player's turn. The losing arrangements involve the losing player's L piece touching a corner. Each player will also soon lose to a perfect player in an additional 14 arrangements. A player will be able to at least force a draw (by playing forever without losing) from the remaining 2267 positions.

Even if neither player plays perfectly, defensive play can continue indefinitely if the players are too cautious to move a neutral piece to the killer positions. If both players are at this level, a sudden-death variant of the rules permits one to move both neutral pieces after moving. A player who can look three moves ahead can defeat defensive play using the standard rules.[clarification needed]

See also

[edit]Reviews

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Games and Puzzles 1974-11: Iss 30". A H C Publications. November 1974.

Other sources

[edit]- de Bono, Edward (1967). "The L Game: Strategic Thinking". The Five-Day Course in Thinking. Basic Books Inc. pp. 149–206. LCCN 67027438.

- Parlett, David (1999). "The L-Game". The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford University Press Inc. pp. 161–62. ISBN 0-19-212998-8.

- Pritchard, D. B. (1982). "The L Game". Brain Games. Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 107–12. ISBN 0-14-00-5682-3.

External links

[edit]L game

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Invention

The L game was invented by Edward de Bono, a Maltese physician, psychologist, philosopher, and author renowned for originating the concept of lateral thinking as a method to foster creative problem-solving.[6] De Bono, who held degrees including an MA in psychology and physiology from Oxford University and a PhD in medicine from Trinity College, Cambridge, developed the game as part of his broader efforts to devise practical tools for enhancing cognitive skills beyond traditional logical approaches.[7] The game's creation stemmed from a specific challenge during a dinner conversation in the mid-1960s at Trinity College, Cambridge, between de Bono and the eminent mathematician John Edensor Littlewood.[8] Littlewood, critiquing the complexity of games like chess, urged de Bono to invent what would be the simplest possible abstract strategy game that nonetheless demanded genuine skill and strategic depth.[8] In response, de Bono designed the L game, utilizing a minimal 4x4 grid and just four pieces to create a contest that balances accessibility with intellectual challenge.[9] This invention aligned with de Bono's intellectual context of promoting innovative thinking tools, drawing from his research into how errors and unconventional patterns could lead to breakthroughs in decision-making.[9] The L game was conceived to encourage players to develop analytical and adaptive thinking skills through a format that is easy to learn—requiring only a few minutes to grasp the basics—yet offers layers of complexity for repeated play and mastery.[8] It exemplified de Bono's philosophy that simplicity in structure could reveal profound insights into human cognition, serving as an educational device rather than mere entertainment.[9] The game was first detailed in de Bono's 1967 book The Five-Day Course in Thinking.[9]Publication and Reception

The L game was first introduced to the public in Edward de Bono's 1967 book The Five-Day Course in Thinking, where it served as a practical example of strategic thinking exercises.[10] Early editions of the book included detachable physical pieces for the game, enabling immediate play, and it was marketed and sold in this format through the late 1960s and 1970s by publishers such as Basic Books and Penguin.[11] The game garnered initial praise for its elegant simplicity combined with notable strategic depth, as highlighted in a 1974 Esquire article that described it as a "ticklish test of strategy" created by de Bono.[12] This reception aligned with the broader 1960s-1970s surge in interest for abstract strategy games, a period marked by innovative designs like those in 3M's bookshelf series, and reflected the growing popularity of de Bono's methodology books on creative and lateral thinking.Game Components

Board

The L game is played on a board consisting of a 4×4 grid, which totals 16 individual squares.[1] This compact size facilitates quick setup and play while providing sufficient space for strategic maneuvering.[3] The board's layout is a plain square grid defined by lines separating the squares, with no additional markings in the standard version of the game.[13] In certain scoring variants, however, the four squares in one corner may be indicated to track points awarded when a player's L-shaped piece touches them.[1] Boards are typically printed on paper for ease of production and reproduction, or crafted from wood or plastic to enhance durability and portability in physical sets.[14] Visually, the grid is often depicted with simple lines or subtle shading to clearly delineate the squares, aiding precise piece placement.[1] The structure supports the sliding and rotation of L-shaped pieces, each covering four contiguous squares.[1]Pieces

The L game utilizes a set of polyomino pieces placed on a 4×4 grid board. Each player controls one L-tetromino, a polyomino consisting of four connected squares arranged in an L shape: three squares forming a straight line with a fourth square attached perpendicularly to one end.[15] These player pieces are distinguishable by color, typically black for one player and white for the other, to clearly identify ownership.[5] In addition to the player pieces, the game includes two neutral 1×1 monomino pieces, each covering a single square. These neutral pieces are unowned and can be manipulated by either player, serving as shared blockers on the board.[16] Unlike the L-tetrominoes, the neutral pieces have no distinct shape beyond their single-square form and are often identical in appearance.[15] The L-tetrominoes possess versatile properties, allowing rotation in 90-degree increments (0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°) as well as flipping (reflection) to adapt to different orientations on the board.[15] The neutral pieces, being simple single squares, lack such transformative properties and function solely as positional obstacles. Collectively, the two L-tetrominoes and two neutral pieces cover a total of 10 squares, leaving 6 squares empty on the 16-square board for strategic placement.[5]Rules

Setup

The L game is prepared on a 4×4 grid board with the players' L-shaped pieces—each consisting of four squares in an L configuration—and two neutral one-square pieces. The black player's L piece is placed in the top-left corner, covering squares (1,1), (1,2), (1,3), and (2,1), while the white player's L piece is placed in the bottom-right corner, covering squares (4,4), (4,3), (4,2), and (3,4). The two neutral pieces are positioned in the remaining opposite corners: one at (1,4) in the top-right and the other at (4,1) in the bottom-left. These placements ensure no overlaps occur at the start and leave the central 2×2 area and other spaces empty for play. The two neutral pieces are identical single-square pieces. To determine the first player, a coin flip or similar random method is used, with the winner choosing to play as black or white; colors are then assigned accordingly. The board must be verified as clear of any additional pieces or obstructions before the game begins.[1]Player Turns

Players alternate turns, with the first player beginning after the initial setup. The game is symmetric at the start, allowing the second player to mirror the first player's moves if possible to maintain balance.[17][14] On a player's turn, they must first move their own L-shaped tetromino, which covers exactly four squares in an L configuration fitting within a 3×2 bounding box. The piece may be slid, rotated, flipped (reflected), or lifted from its current position and repositioned anywhere on the 4×4 board, provided it covers at least one different square than before—thus prohibiting placement in the exact same location and orientation. Up to eight possible orientations are permitted.[5][17] The repositioned L-tetromino must lie entirely within the board boundaries and cover exactly four empty squares or squares that were previously occupied by the moving piece itself (now vacated). It cannot overlap with the opponent's L-tetromino or either of the two neutral 1×1 pieces.[5][17] Following the mandatory L-tetromino move, the player may optionally relocate one of the two neutral pieces to any empty square on the board, with no restrictions on distance or adjacency to its prior position. This neutral move is entirely at the player's discretion and does not affect the legality of the L placement.[5][17]Winning Condition

In the L game, a player wins by completing their turn in such a way that the opponent has no legal move available for their L-shaped piece.[13] A legal move consists of repositioning the L piece—through sliding, rotating, or flipping—to a new location on the 4×4 board that covers at least one unoccupied square previously not covered by that piece, without overlapping any other pieces or extending beyond the board edges.[1] Following the L piece movement, the player may optionally relocate one of the two neutral 1×1 pieces to any empty square, but this step does not affect the validity of the opponent's subsequent turn.[3] The game ends immediately upon the opponent's inability to move, with no additional plays or scoring required; there is no points system or alternative victory paths in the standard rules.[13] Unlike some games, the L game does not recognize draws by repetition or perpetual checks; play continues indefinitely until an impasse occurs, at which point the unable player loses.[1] While the core rules emphasize movement denial as the sole win criterion, certain house variants introduce alternative objectives, such as scoring points for touching board corners with the L piece, but these are not part of the original standard ruleset.[20]Strategy

Basic Principles

In the L game, controlling space is key to restricting the opponent's mobility. Players aim to position their L-tetromino to limit the possible moves for the opponent's piece while maintaining their own flexibility.[4] The two neutral pieces can be used to block the opponent's potential positions after moving one's own L-tetromino. These pieces are shared and optional to move, emphasizing their role in disrupting the adversary.[1] The game's symmetric starting position encourages players to consider reflections and rotations. The first player can gain initiative by making an asymmetric move to disrupt balance and force reactive play from the opponent.[4] Players should position their L-tetromino to ensure multiple possible moves remain available after their turn, avoiding self-immobilization and sustaining play.[1]Advanced Tactics

A common advanced technique is to block a 3×3 corner subgrid using one's L-tetromino and a neutral piece to trap the opponent's L-tetromino, limiting its rotations and translations. This requires careful timing to prevent the opponent from escaping.[4] The eight non-corner perimeter squares, known as killer spaces, are strategic targets for neutral placement, as they help restrict the opponent's perimeter mobility and force it into confined areas.[1] Strategic use of the neutral pieces involves positioning them to block opponent escapes while preserving one's own options, often by anticipating and countering potential responses.[16] Players can create forcing sequences by rotating and translating the L-tetromino to limit the opponent's replies, gradually restricting its movement until no legal move remains.[1]Analysis

Positional Evaluation

In the L game, positional evaluation centers on assessing the board state through the lens of mobility and the constraints imposed by piece interactions, enabling players to gauge the viability of current and future moves. A fundamental aspect involves enumerating valid arrangements for the L-tetrominoes. On an empty 4×4 board, there are numerous legal placements for a single L-tetromino, accounting for all possible orientations and positions that cover exactly four squares without overlap. However, when both players' L-tetrominoes and the two neutral pieces are considered, interactions such as overlaps and blockages drastically reduce the number of feasible configurations, often leaving only a subset of these placements available depending on the opponent's positioning. Certain board states constitute immediate losing positions, where the current player has no legal move for their L-tetromino. Specifically, there are 15 such losing positions per player in which the L-tetromino touches a corner of the board and is thereby immobilized, unable to shift to any adjacent legal covering without violating rules. These positions arise from constrained setups where the opponent's L-tetromino and neutrals hem in the vulnerable piece, preventing any reconfiguration that covers at least one new square. Identifying these early allows for proactive avoidance through prior moves that force the opponent toward similar constraints. Mobility serves as a core quantitative metric in evaluating positions, calculated by counting the number of distinct legal moves available to the current player's L-tetromino from the given state. Positions with high mobility (e.g., 8 or more options) offer flexibility and control, allowing the player to maintain pressure or evade threats. Conversely, low mobility—particularly fewer than 3 available moves—signals vulnerability, as it limits escape routes and invites the opponent to execute tactical blocks that further restrict options. Players thus prioritize moves that maximize their own mobility while minimizing the opponent's, often by leveraging the board's central squares for greater rotational freedom. The neutral pieces, movable at the player's discretion after an L-tetromino shift, significantly influence positional dynamics by altering the effective board space. With two neutrals occupying squares, they reduce the playable area to 14 squares available for L-tetromino maneuvers, intensifying the impact of blockades and making central control even more critical. Strategic placement of neutrals in perimeter non-corner "killer spaces" can amplify these constraints, turning neutral mobility into a tool for defensive solidification or offensive setup without directly favoring either player.Theoretical Outcome

The L game has been fully solved through exhaustive enumeration of its finite state space, revealing that with perfect play from both sides, the game ends in a draw.[21] There are 2,296 distinct valid board configurations, excluding rotations and reflections.[21] Among these, the initial position is a draw, with no advantage for the first player.[21] Fifteen positions are immediate losses, where the current player's L-piece is completely blocked and cannot be moved legally.[21] An additional 14 positions lead to a loss against optimal opponent responses, with the maximum depth to forced win being five moves.[21] The remaining 2,267 configurations permit perpetual play without either player achieving a win, allowing the disadvantaged side to force a draw indefinitely.[21] This outcome was established via early computational enumeration in combinatorial game theory literature.References

- https://www.[instructables](/page/Instructables).com/L-Game-With-Wood-Board/

- https://web.[archive](/page/Archive).org/web/20070208222510/http://www.edwdebono.com/debono/lgame.htm