Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lower Dir District

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

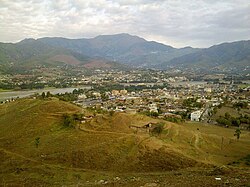

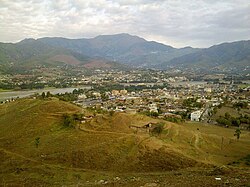

Lower Dir District (Pashto: ښکته دير ولسوالۍ, Urdu: ضلع دیر زیریں) is a district in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan.[3] Timergara is the district's headquarters and largest city.[3] The Lower Dir district was formed in 1996, when Dir District was divided into Upper Dir and Lower Dir districts.[3] On 22 January 2023, both Lower Dir and Upper Dir districts were further bifurcated to create a new Central Dir District.[4]

Key Information

Lower Dir district borders with Swat District to the east, Afghanistan to the west, Upper Dir to the north and Malakand and Bajaur District to the south.

History

[edit]At the time of independence of Pakistan, Dir was a princely state ruled by Nawab Shah Jehan Khan. Dir was merged with Pakistan in 1969, declared a district in 1970, and split into Upper and Lower Dir in 1996.[3]

Education

[edit]- The University of Malakand is a public university located in Chakdara.

- The University of Dir is a newly established university located in Timergara.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 277,481 | — |

| 1981 | 404,844 | +4.29% |

| 1998 | 717,649 | +3.42% |

| 2017 | 1,436,082 | +3.72% |

| 2023 | 1,650,183 | +2.34% |

| Sources:[5][1] | ||

As of the 2023 census, Lower Dir district has 202,836 households and a population of 1,650,183. The district has a sex ratio of 97.24 males to 100 females and a literacy rate of 57.36%: 72.57% for males and 43.16% for females. 542,074 (32.88% of the surveyed population) are under 10 years of age. 47,860 (2.90%) live in urban areas.[1] 4,439 (0.27%) people in the district were from religious minorities, mainly Christians.[6] Pashto was the predominant language, spoken by 99.54% of the population.[7]

Administration

[edit]National Assembly

[edit]NA-6 (Lower Dir-I) and NA-7 (Lower Dir-II) are constituencies of the National Assembly of Pakistan from Lower Dir district. These areas were formerly part of NA-34 (Lower Dir) constituency from 1977 to 2018. The delimitation in 2018 split Lower Dir into two separate constituencies, NA-6 (Lower Dir-I) and NA-7 (Lower Dir-II).

NA-34 constituency (2002-2018)

[edit]| Member of National Assembly | Party affiliation | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Qazi Hussain Ahmad | Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal | 2002 |

| Maulana Ahmad Ghafoor Ghawas | Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal | 2003 |

| Malak Azmat Khan | Pakistan Peoples Party | 2008 |

| Shahib Zada Muhammad Yaqub | Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan | 2013 |

Since 2018: NA-6 (Lower Dir-I) and NA-7 (Lower Dir-II)

[edit]| Member of National Assembly | Party affiliation | Constituency | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mehboob Shah | PTI | NA-6 (Lower Dir-I) | 2018 |

| Muhammad Bashir Khan | PTI | NA-7 (Lower Dir-II) | 2018 |

Provincial Assembly

[edit]| Member of Provincial Assembly | Party affiliation | Constituency | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muhammad Azam Khan | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-13 (Lower Dir-I) | 2018 |

| Humayun Khan | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-14 (Lower Dir-II) | 2018 |

| Shafi ullah | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-15 (Lower Dir-III) | 2018 |

| Bahdur Khan | Awami National Party | PK-16 (Lower Dir-IV) | 2018 |

| Liaqat Ali Khan | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-17 (Lower Dir-V) | 2018 |

Tehsils

[edit]| Tehsil | Area

(km²)[8] |

Pop.

(2023) |

Density

(ppl/km²) (2023) |

Literacy rate

(2023)[9] |

Union Councils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenzai Tehsil | 372 | 378,915 | 1,018.59 | 62.19% | |

| Balambat Tehsil | ... | ... | ... | ... | |

| Khal Tehsil | ... | ... | ... | ... | |

| Lal Qilla Tehsil | 216 | 247,381 | 1,145.28 | 53.29% | |

| Munda Tehsil | ... | ... | ... | ... | |

| Samar Bagh Tehsil | 419 | 427,714 | 1,020.80 | 45.75% | |

| Timergara Tehsil | 576 | 596,173 | 1,035.02 | 64.06% |

Notable people

[edit]- Nawabzada Shahabuddin Khan, Former Ruler of Lower Dir[10][11]

- Siraj ul Haq, politician

- Muhammad Bashir Khan, politician

- Jehan Alam Khan, President / Head of World Yousafzai Jirga (WYJ)

- Naseem Shah, cricketer

- Zahid Khan, Ex-Senator

- Abaseen Yousafzai, Pashto poet

- Noorena Shams , squash player

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 1" (PDF). www.pbscensus.gov.pk. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "Literacy rate, enrolments, and out-of-school population by sex and rural/urban, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d "About District". Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: Deputy Commissioner Dir Lower.

- ^ "KP gets another district". Dunya News. 2023-01-18. Retrieved 2024-07-14.

- ^ "Population by administrative units 1951-1998" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 9" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 11" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "TABLE 1 : AREA, POPULATION BY SEX, SEX RATIO, POPULATION DENSITY, URBAN POPULATION, HOUSEHOLD SIZE AND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

- ^ "LITERACY RATE, ENROLMENT AND OUT OF SCHOOL POPULATION BY SEX AND RURAL/URBAN, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

- ^ "Tribe seeks ban on sale, purchase of shared land". www.thenews.com.pk.

- ^ High Court, Peshawar (17 November 2016). "Judgment Sheet In The Peshawar High Court - The Government Of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa & Others Vs. Nawabzada Muhammad Shahabuddin Through Lrs & Others" (PDF). Retrieved 18 January 2024.

External links

[edit]Lower Dir District

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Borders

Lower Dir District is situated in the northwestern region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan, encompassing an area of 1,583 square kilometers.[5] It lies between latitudes 34°22' N and 35° N and longitudes 71°02' E and 72° E, positioning it in a strategically vital area near the border with Afghanistan.[3] The district shares its northern boundary with Upper Dir District and its northwestern boundary with Chitral District, while to the east it adjoins Swat District and to the southeast Malakand District.[4] To the southwest lies Bajaur District, and critically, its western frontier directly borders Afghanistan along segments of the Durand Line, the 2,640-kilometer international boundary established in 1893.[4] This proximity facilitates cross-border interactions, including informal trade routes and population movements, but also heightens security challenges due to the porous nature of the terrain along the Durand Line.[6] The Panjkora River traverses the district from north to south, forming a key hydrological feature that influences local geography and connectivity.[3] This riverine path underscores the district's role in regional water systems and transportation corridors linking it to adjacent areas.[7]Topography and Climate

Lower Dir District occupies a rugged mountainous terrain within the Hindu Kush system, characterized by steep slopes, deep valleys, and elevated plateaus. Elevations span from about 1,200 meters in the lower Panjkor Valley to exceeding 2,800 meters at higher peaks, where snow-capped summits prevail during winter. Western areas feature coniferous forests, contrasting with more barren eastern ridges, fostering diverse ecological zones that shape local hydrology and soil stability.[3][8] Climatic conditions vary markedly with altitude, producing subtropical characteristics in lower valleys and temperate to alpine regimes at higher elevations. In lowland areas like Timergara, summer highs routinely exceed 38°C, with occasional peaks near 40°C, while winters remain mild with lows around 2°C; higher altitudes experience cooler summers below 25°C and prolonged snowfall, often accumulating several meters. Annual rainfall averages 1,400–1,500 mm, concentrated in the July–September monsoon, supplemented by winter western disturbances, though totals can fluctuate significantly year-to-year.[9][10][11] This elevational diversity generates microclimates that dictate habitability and resource distribution, with lower zones supporting year-round settlement due to warmer conditions and reliable water from rivers like the Panjkora, whereas upper reaches limit permanent habitation to seasonal use amid frost risks and inaccessibility. Heavy precipitation, combined with steep gradients, heightens vulnerability to flash floods and landslides, as evidenced by recurrent events triggered by monsoon downpours exceeding 300 mm in short bursts.[12][13]History

Pre-Colonial and Dir Princely State Era

The Dir region, centered in the Panjkora Valley, saw the establishment of a distinct polity in the 17th century under the Akhund Khel lineage of the Malizai Yusufzai Pashtuns, a sub-tribe that had migrated and asserted control over the area from the preceding century onward by displacing or assimilating prior inhabitants.[14] The foundational figure was Akhund Ilyas, also known as Mullah Ilyas Khan or Akhund Baba, a religious leader and spiritual authority whose influence derived from his Baizai Yusufzai roots and role in fostering clan cohesion, thereby enabling the Melazai (Malizai) clan's early dominance.[15] His descendants formalized rule starting around 1626, initially under the title of Khan, transforming tribal settlements into a semi-autonomous entity reliant on Pashtunwali codes and kinship networks rather than centralized bureaucracy.[16] Governance in this era hinged on navigating endemic Pashtun tribal feuds, which often pitted Yusufzai clans against neighbors like the Utman Khel or internal rivals, while power struggles within the Akhund Khel tested familial succession.[17] Rulers such as Mulla Ismail (r. 1676–1752) and Ghulam Khan Baba (r. 1752–1804) maintained authority through alliances with local jirgas and selective warfare, preserving the state's cohesion amid disputes over land, grazing rights, and revenge obligations that characterized the rugged valley's social order.[14] This tribal framework ensured resilience against external pressures from Mughal or Afghan incursions, emphasizing decentralized decision-making and honor-based mediation over imperial oversight.[15] Subsequent Khans, including Zafar Khan (r. 1804–1814) and Qasim Khan (r. 1814–1856), perpetuated Akhund Khel rule by balancing clan loyalties and suppressing revolts, such as those from rival septs within the Painda Khel, thereby sustaining the principality's internal stability through a blend of religious legitimacy inherited from Akhund Ilyas and martial prowess.[14] These dynamics underscored the Dir state's character as a product of Yusufzai migration and consolidation, where governance emerged organically from feuds resolved via councils rather than conquest, fostering a legacy of autonomy in the pre-modern frontier.[16]British Colonial Period and Integration

The British Raj incorporated Dir into its frontier strategy during the late 19th century as part of the broader North-West Frontier Province administration, recognizing the Nawabs as semi-independent rulers under a subsidiary alliance to maintain stability against Afghan incursions and potential Russian advances in the Great Game era. Dir's rugged, mountainous geography, straddling key passes near the Afghan border, positioned it as a natural buffer zone, prompting pragmatic agreements focused on border security rather than direct annexation; archival records indicate British priorities centered on securing supply routes and tribal loyalty through subsidies and arms rather than ideological expansion.[18][19] In 1895, following the British Chitral Expedition, the Khan of Dir received the title of Nawab in recognition of logistical support provided to imperial forces, solidifying the alliance; this was formalized through boundary agreements in December 1898 delineating Dir's limits with Swat, Chitral, Bajaur, and Afghanistan, alongside commitments to keep vital roads like Chakdara to Ashreth open for British transit. The Sandeman-influenced frontier policy, emphasizing indirect rule via tribal intermediaries, extended partially to Dir, where British agents coordinated with Nawabs to manage Yusufzai Pashtun clans, averting revolts through allowances rather than full military occupation, as evidenced by cooperation during earlier Afghan conflicts like 1847-1848. Nawab Aurangzeb Khan, ruling from 1904 to 1925 with intermittent British backing, navigated alliances amid tribal unrest, prioritizing realpolitik containment of cross-border threats over internal reforms.[20][21][22] Under Nawab Muhammad Shah Jehan Khan, who ascended in November 1924, Dir maintained this semi-autonomy until the partition of British India; facing geopolitical pressures, he signed an accession instrument on October 7, 1947, integrating the state into the Dominion of Pakistan, with Dir's forces subsequently aiding Pakistani operations in the First Kashmir War. This transition reflected the Nawabs' strategic alignment with the emerging state to preserve influence, though initial reluctance stemmed from Dir's frontier isolation, underscoring how British-era treaties had entrenched a buffer role that eased incorporation without immediate resistance.[23]Post-Independence and Division into Districts

Following accession to Pakistan on November 8, 1947, Dir retained its princely status as a special area within the North-West Frontier Province (later Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), with the Nawab exercising internal autonomy under central oversight.[24] This arrangement persisted until 1969, when President Yahya Khan enacted the Dir, Chitral, and Swat Administration Regulation, fully integrating the state by abolishing the Nawabi system and imposing a bureaucratic framework modeled on provincial administration.[25] Land reforms in the 1950s and 1970s further dismantled feudal landholdings held by the ruling elite, redistributing them to tenants and eroding traditional power bases, though implementation faced pushback from tribal leaders who viewed centralized taxation and judicial reforms as encroachments on customary authority. Dir was formally declared a district in 1970, marking its transition to standard provincial governance.[26] The expansive and rugged terrain of Dir District strained administrative capacity as population pressures mounted, prompting its bifurcation on July 31, 1996, into Lower Dir and Upper Dir districts to facilitate more targeted governance and resource allocation.[27] Lower Dir, comprising the relatively accessible southern plains and valleys along the Panjkora River, retained Timergara as its headquarters, enabling improved connectivity and service provision in lowland tehsils like Chakdara and Balambat, while Upper Dir addressed the remote, mountainous north. This division created distinct administrative units—Lower Dir with five tehsils and over 37 union councils—aimed at decentralizing control and mitigating logistical challenges in a frontier region historically peripheral to federal priorities. Post-division demographics underscored the efficacy of subdivided governance, with Lower Dir's population rising from 717,649 in the 1998 census to 1,436,082 by 2017, at an average annual growth rate of 3.42%, fueled by sustained fertility rates exceeding 4 children per woman and modest infrastructure-driven retention of residents.[28] Enhanced local institutions, including expanded revenue collection and development budgeting, correlated with incremental state penetration, yet persistent tribal affiliations and resistance to uniform bureaucratic norms perpetuated tensions between central directives and regional autonomy, as evidenced by uneven reform adoption in rural khans' domains.Insurgency and Military Operations (2000s–Present)

Following the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, Taliban-linked militants relocated to Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and nearby settled districts, including Lower Dir, leveraging the district's proximity to the Afghan border for cross-border movement and sanctuary.[29] These groups, motivated by jihadist ideology aimed at establishing Islamic emirates and opposing perceived apostate governments, began establishing footholds in Lower Dir by the mid-2000s, using local madrassas for ideological indoctrination and recruitment of fighters committed to defensive jihad against Pakistani forces.[30][31] The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), formed in December 2007 as an umbrella of militant factions, expanded into Lower Dir, treating it as a logistical base for incursions into adjacent Swat district, where TTP commander Maulana Fazlullah's forces imposed sharia rule.[32] By early 2009, TTP militants, advancing from Swat under the Tehreek-e-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi banner, briefly seized control of areas in Lower Dir and neighboring Buner, enforcing strict edicts, destroying girls' schools, and launching attacks on security posts to consolidate territorial gains. This control facilitated TTP's broader campaign against the Pakistani state, with Dir serving as a conduit for weapons and fighters from FATA. In response, the Pakistani military initiated Operation Rah-e-Rast on May 5, 2009, targeting TTP strongholds across the Malakand Division, including Lower Dir, resulting in the displacement of approximately 100,000 residents from the district amid intense fighting that cleared militants from key areas by June.[33] The operation inflicted heavy casualties on TTP forces, with Pakistani claims of over 1,400 militants killed in Malakand-wide engagements, though independent verification remains limited; security forces reported 70 troops killed in Lower Dir and Buner clashes alone.[34] Subsequent operations, such as Rah-e-Nijat in South Waziristan, further disrupted TTP logistics spilling into Dir. Post-2014, following nationwide offensives like Zarb-e-Azb, TTP remnants and Afghan Taliban affiliates maintained low-level threats in Lower Dir through sporadic bombings and ambushes, exacerbated by cross-border sanctuaries after the Afghan Taliban's 2021 takeover.[35] Recruitment persists via ideologically charged madrassas promoting anti-state jihad, underscoring causal drivers rooted in doctrinal appeals over socioeconomic grievances, as evidenced by sustained militant mobilization despite infrastructure improvements.[31] Pakistani forces continue targeted raids, neutralizing dozens of TTP operatives annually in the district, though TTP-claimed attacks rose to over 70 in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa border areas by 2023.[36]Demographics

Population Statistics

According to the 2023 Pakistan census conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Lower Dir District had a total population of 1,650,183, comprising 813,551 males and 836,605 females.[2] The sex ratio stood at 97.24 males per 100 females.[2] The district spans 1,583 square kilometers, yielding a population density of 1,042 persons per square kilometer.[2] The population has exhibited consistent growth over recent decades, as reflected in census data:| Census Year | Population | Annual Growth Rate (from prior census) |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 779,056 | - |

| 2017 | 1,436,082 | 2.81% (1998–2017) |

| 2023 | 1,650,183 | 2.35% (2017–2023) |