Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

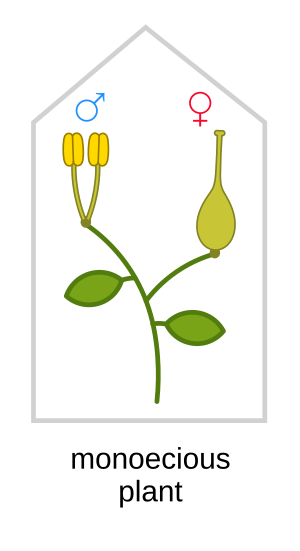

Monoecy

View on Wikipedia

Monoecy (/məˈniːsi/; adj. monoecious /məˈniːʃəs/)[1] is a sexual system in seed plants where separate male and female cones or flowers are present on the same plant.[2] It is a monomorphic sexual system comparable with gynomonoecy, andromonoecy and trimonoecy, and contrasted with dioecy where individual plants produce cones or flowers of only one sex, and with bisexual or hermaphroditic plants in which male and female gametes are produced in the same flower.[3]

Monoecy often co-occurs with anemophily,[2] because it prevents self-pollination of individual flowers and reduces the probability of self-pollination between male and female flowers on the same plant.[4]: 32

Monoecy in angiosperms has been of interest for evolutionary biologists since Charles Darwin.[5]

Terminology

[edit]Monoecious comes from the Greek words for one house.[6]

History

[edit]The term monoecy was first introduced in 1735 by Carl Linnaeus.[2] Darwin noted that the flowers of monoecious species sometimes showed traces of the opposite sex function, suggesting that they evolved via hermaphroditism.[7] Monoecious hemp was first reported in 1929.[8]

Occurrence

[edit]Monoecy is most common in temperate climates[9] and is often associated with inefficient pollinators or wind-pollinated plants.[10][11] It may be beneficial to reducing pollen-stigma interference,[clarification needed] thus increasing seed production.[12]

Around 10% of all seed plant species are monoecious.[9] It is present in 7% of angiosperms.[4]: 8 Most Cucurbitaceae are monoecious[13] including most watermelon cultivars.[14] It is prevalent in Euphorbiaceae.[15][16] Dioecy is replaced by monoecy in polyploid populations of Mercurialis annua.[17]

Maize

[edit]Maize is monoecious since both pistillate (female) and stamenate (male) flowers occur on the same plant. The pistillate flowers are present on the ears of corn and the stamenate flowers are in the tassel at the top of the stalk. In the ovules of the pistillate flowers, diploid cells called megaspore mother cells undergo meiosis to produce haploid megaspores. In the anthers of the stamenate flowers, diploid pollen mother cells undergo meiosis to produce pollen grains. Meiosis in maize requires gene product RAD51, a protein employed in recombinational repair of DNA double-strand breaks.[18]

Evolution

[edit]The evolution of monoecy has received little attention.[7]

Male and female flowers evolve from hermaphroditic flowers[19] via andromonoecy or gynomonoecy.[20]: 148

In amaranths monoecy may have evolved from hermaphroditism through various processes caused by male sterility genes and female fertility genes.[20]: 150

Monoecy may be an intermediate state between hermaphroditism and dioecy.[21] Evolution from dioecy to monoecy probably involves disruptive selection on floral sex ratios.[22]: 65 Monoecy is also considered to be a step in the evolutionary pathway from hermaphroditism towards dioecy.[23]: 91 Some authors even argue monoecy and dioecy are related.[2] But, there is also evidence that monoecy is a pathway from sequential hermaphroditism to dioecy.[23]: 8

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "monoecious". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Batygina, T. B. (2019-04-23). Embryology of Flowering Plants: Terminology and Concepts, Vol. 3: Reproductive Systems. CRC Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4398-4436-6.

- ^ Torices, Rubén; Méndez, Marcos; Gómez, José María (2011). "Where do monomorphic sexual systems fit in the evolution of dioecy? Insights from the largest family of angiosperms". New Phytologist. 190 (1): 234–248. Bibcode:2011NewPh.190..234T. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03609.x. ISSN 1469-8137. PMID 21219336.

- ^ a b Karasawa, Marines Marli Gniech (2015-11-23). Reproductive Diversity of Plants: An Evolutionary Perspective and Genetic Basis. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-21254-8.

- ^ Nozaki, Hisayoshi; Mahakham, Wuttipong; Heman, Wirawan; Matsuzaki, Ryo; Kawachi, Masanobu (2020-07-02). "A new preferentially outcrossing monoicous species of Volvox sect. Volvox (Chlorophyta) from Thailand". PLOS ONE. 15 (7) e0235622. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1535622N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235622. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7332039. PMID 32614898.

- ^ Purves, William K.; Sadava, David E.; Orians, Gordon H.; Heller, H. Craig (2001). Life: The Science of Biology. Macmillan. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-7167-3873-2.

- ^ a b Pedersen, Roger A.; Schatten, Gerald P. (1998-02-03). Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Academic Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-08-058461-4.

- ^ Rowell, Roger M.; Rowell, Judith (1996-10-15). Paper and Composites from Agro-Based Resources. CRC Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-56670-235-5.

- ^ a b Willmer, Pat (2011-07-05). Pollination and Floral Ecology. Princeton University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4008-3894-3.

- ^ Glover, Beverley (February 2014). Understanding Flowers and Flowering Second Edition. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-19-966159-6.

- ^ Friedman, Janice; Barrett, Spencer C. H. (January 2009). "The Consequences of Monoecy and Protogyny for Mating in Wind-Pollinated Carex". The New Phytologist. 181 (2): 489–497. Bibcode:2009NewPh.181..489F. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02664.x. JSTOR 30224692. PMID 19121043.

- ^ Patiny, Sébastien (2011-12-08). Evolution of Plant-Pollinator Relationships. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-139-50407-2.

- ^ Pessarakli, Mohammad (2016-02-22). Handbook of Cucurbits: Growth, Cultural Practices, and Physiology. CRC Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-4822-3459-6.

- ^ Prohens-Tomás, Jaime; Nuez, Fernando (2007-12-06). Vegetables I: Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Chenopodicaceae, and Cucurbitaceae. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-387-30443-4.

- ^ Webster, G. L. (2014). "Euphorbiaceae". In Kubitzki, Klaus (ed.). The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants - Volume XI - Flowering Plants, Eudicots - Malpighiales. Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 51–216/x+331. ISBN 978-3-642-39416-4. OCLC 868922400. ISBN 978-3-642-39417-1. ISBN 3642394167.

- ^ Bahadur, Bir; Sujatha, Mulpuri; Carels, Nicolas (2012-12-14). Jatropha, Challenges for a New Energy Crop: Volume 2: Genetic Improvement and Biotechnology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4614-4915-7.

- ^ Volz, Stefanie M.; Renner, Susanne S. (2008). "Hybridization, polyploidy and evolutionary transitions between monoecy and dioecy in Bryonia (Cucurbitaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 95 (10): 1297–1306. doi:10.3732/ajb.0800187. PMID 21632334.

- ^ Li J, Harper LC, Golubovskaya I, Wang CR, Weber D, Meeley RB, McElver J, Bowen B, Cande WZ, Schnable PS (July 2007). "Functional analysis of maize RAD51 in meiosis and double-strand break repair". Genetics. 176 (3): 1469–82. doi:10.1534/genetics.106.062604. PMC 1931559. PMID 17507687.

- ^ Núñez-Farfán, Juan; Valverde, Pedro Luis (2020-07-30). Evolutionary Ecology of Plant-Herbivore Interaction. Springer Nature. p. 177. ISBN 978-3-030-46012-9.

- ^ a b Das, Saubhik (2016-07-25). Amaranthus: A Promising Crop of Future. Springer. ISBN 978-981-10-1469-7.

- ^ Kinney, M.S.; Columbus, J.T.; Friar, E.A. (2007). "Dicliny in Bouteloua (Poaceae: Chloridoideae): Implications for the evolution of dioecy". Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Floristic Botany. 23 (1): 605–614.

- ^ Avise, John (2011-03-15). Hermaphroditism: A Primer on the Biology, Ecology, and Evolution of Dual Sexuality. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15386-7.

- ^ a b Leonard, Janet L. (2019-05-21). Transitions Between Sexual Systems: Understanding the Mechanisms of, and Pathways Between, Dioecy, Hermaphroditism and Other Sexual Systems. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-94139-4.