Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

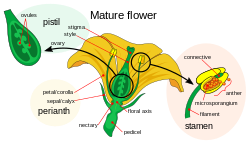

Stamen

View on Wikipedia

The stamen (pl.: stamina or stamens) is a part consisting of the male reproductive organs of a flower. Collectively, the stamens form the androecium.[1]

Morphology and terminology

[edit]

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filament and an anther which contains microsporangia. Most commonly, anthers are two-lobed (each lobe is termed a locule) and are attached to the filament either at the base or in the middle area of the anther. The sterile (i.e. nonreproductive) tissue between the lobes is called the connective, an extension of the filament containing conducting strands. It can be seen as an extension on the dorsal side of the anther. A pollen grain develops from a microspore in the microsporangium and contains the male gametophyte. The size of anthers differs greatly, from a tiny fraction of a millimeter in Wolfia spp up to five inches (13 centimeters) in Canna iridiflora and Strelitzia nicolai.

The stamens in a flower are collectively called the androecium. The androecium can consist of as few as one-half stamen (i.e. a single locule) as in Canna species or as many as 3,482 stamens which have been counted in the saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea).[2] The androecium in various species of plants forms a great variety of patterns, some of them highly complex.[3][4][5][6] It generally surrounds the gynoecium and is surrounded by the perianth. A few members of the family Triuridaceae, particularly Lacandonia schismatica and Lacandonia brasiliana,[7] along with a few species of Trithuria (family Hydatellaceae) are exceptional in that their gynoecia surround their androecia.

Etymology

[edit]- Stamen is the Latin word meaning "thread" (originally thread of the warp, in weaving).[8]

- Filament derives from classical Latin filum, meaning "thread"[8]

- Anther derives from French anthère,[9] from classical Latin anthera, meaning "medicine extracted from the flower"[10][11] in turn from Ancient Greek ἀνθηρά (anthērá),[9][11] feminine of ἀνθηρός (anthērós) meaning "flowery",[12] from ἄνθος[9] (ánthos) meaning "flower"[12]

- Androecium (pl.: androecia) derives from Ancient Greek ἀνήρ (anḗr) meaning "man",[12] and οἶκος (oîkos) meaning "house" or "chamber/room".[12]

Variation in morphology

[edit]

Depending on the species of plant, some or all of the stamens in a flower may be attached to the petals or to the floral axis. They also may be free-standing or fused to one another in many different ways, including fusion of some but not all stamens. The filaments may be fused and the anthers free, or the filaments free and the anthers fused. Rather than there being two locules, one locule of a stamen may fail to develop, or alternatively the two locules may merge late in development to give a single locule.[13] Extreme cases of stamen fusion occur in some species of Cyclanthera in the family Cucurbitaceae and in section Cyclanthera of genus Phyllanthus (family Euphorbiaceae) where the stamens form a ring around the gynoecium, with a single locule.[14] Plants having a single stamen are referred to as "monandrous."

Pollen production

[edit]A typical anther contains four microsporangia. The microsporangia form sacs or pockets (locules) in the anther (anther sacs or pollen sacs). The two separate locules on each side of an anther may fuse into a single locule. Each microsporangium is lined with a nutritive tissue layer called the tapetum and initially contains diploid pollen mother cells. These undergo meiosis to form haploid spores. The spores may remain attached to each other in a tetrad or separate after meiosis. Each microspore then divides mitotically to form an immature microgametophyte called a pollen grain.

The pollen is eventually released when the anther forms openings (dehisces). These may consist of longitudinal slits, pores, as in the heath family (Ericaceae), or by valves, as in the barberry family (Berberidaceae). In some plants, notably members of the Orchidaceae and Asclepiadoideae families, the pollen remains in masses called pollinia, which are adapted to attach to particular pollinating agents such as birds or insects. More commonly, mature pollen grains separate and are dispensed by wind or water, pollinating insects, birds or other pollination vectors.

Pollen of angiosperms must be transported to the stigma, the receptive surface of the carpel, of a compatible flower, for successful pollination to occur. After arriving, the pollen grain (an immature microgametophyte) typically completes its development. It may grow a pollen tube and undergo mitosis to produce two sperm nuclei.

Sexual reproduction in plants

[edit]

In the typical flower (that is, in the majority of flowering plant species) each flower has both carpels and stamens. In some species, however, the flowers are unisexual with only carpels or stamens. (monoecious = both types of flowers found on the same plant; dioecious = the two types of flower found only on different plants). A flower with only stamens is called androecious. A flower with only carpels is called gynoecious.

A pistil consists of one or more carpels. A flower with functional stamens but no functional pistil is called a staminate flower, or (inaccurately) a male flower. A flower with a functional pistil but no functional stamens is called a pistillate flower, or (inaccurately) a female flower.[15]

An abortive or rudimentary stamen is called a staminodium or staminode, such as in Scrophularia nodosa.

The carpels and stamens of orchids are fused into a column.[16] The top part of the column is formed by the anther, which is covered by an anther cap.

Terminology

[edit]- Stamen

Stamens can also be adnate (fused or joined from more than one whorl):

- epipetalous: adnate to the corolla

- epiphyllous: adnate to undifferentiated tepals (as in many Liliaceae)

They can have different lengths from each other:

- didymous: two equal pairs

- didynamous: occurring in two pairs, a long pair and a shorter pair

- tetradynamous: occurring as a set of six stamens with four long and two shorter ones

or respective to the rest of the flower (perianth):

- exserted: extending beyond the corolla

- included: not extending beyond the corolla

They may be arranged in one of two different patterns:

- spiral; or

- whorled: one or more discrete whorls (series)

They may be arranged, with respect to the petals:

- diplostemonous: in two whorls, the outer alternating with the petals, while the inner is opposite the petals.

- haplostemenous: having a single series of stamens, equal in number to the proper number of petals and alternating with them

- obdiplostemonous: in two whorls, with twice the number of stamens as petals, the outer opposite the petals, inner opposite the sepals, e.g. Simaroubaceae (see diagram)

- Connective

Where the connective is very small, or imperceptible, the anther lobes are close together, and the connective is referred to as discrete, e.g. Euphorbia pp., Adhatoda zeylanica. Where the connective separates the anther lobes, it is called divaricate, e.g. Tilia, Justicia gendarussa. The connective may also be a long and stalk-like, crosswise on the filament, this is a distractile connective, e.g. Salvia. The connective may also bear appendages, and is called appendiculate, e.g. Nerium odorum and some other species of Apocynaceae. In Nerium, the appendages are united as a staminal corona.

- Filament

A column formed from the fusion of multiple filaments is known as an androphore. Stamens can be connate (fused or joined in the same whorl) as follows:

- extrorse: anther dehiscence directed away from the centre of the flower. Cf. introrse, directed inwards, and latrorse towards the side.[17]

- monadelphous: fused into a single, compound structure

- declinate: curving downwards, then up at the tip (also – declinate-descending)

- diadelphous: joined partially into two androecial structures

- pentadelphous: joined partially into five androecial structures

- synandrous: only the anthers are connate (such as in the Asteraceae). The fused stamens are referred to as a synandrium.

- Anther

Anther shapes are variously described by terms such as linear, rounded, sagittate, sinuous, or reniform.

The anther can be attached to the filament's connective in two ways:[18]

- basifixed: attached at its base to the filament

- pseudobasifixed: a somewhat misnomer configuration where connective tissue extends in a tube around the filament tip

- dorsifixed: attached at its center to the filament, usually versatile (able to move)

Gallery

[edit]-

Scanning electron microscope image of Pentas lanceolata anthers, with pollen grains on surface

-

Lily stamens with prominent red anthers and white filaments

-

Calliandra surinamensis petalized stamens

-

Sterculia foetida stamens

-

Stamen of a Grevillea robusta

-

Commelina communis three different types of stamens

References

[edit]- ^ Beentje, Henk (2010). The Kew Plant Glossary. Richmond, Surrey: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-1-84246-422-9., p. 10

- ^ Charles E. Bessey in SCIENCE Vol. 40 (November 6, 1914) p. 680.

- ^ Sattler, R. 1973. Organogenesis of Flowers. A Photographic Text-Atlas. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-1864-5.

- ^ Sattler, R. 1988. A dynamic multidimensional approach to floral morphology. In: Leins, P., Tucker, S. C. and Endress, P. (eds) Aspects of Floral Development. J. Cramer, Berlin, pp. 1–6. ISBN 3-443-50011-0

- ^ Greyson, R. I. 1994. The Development of Flowers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506688-X.

- ^ Leins, P. and Erbar, C. 2010. Flower and Fruit. Schweizerbart Science Publishers, Stuttgart. ISBN 978-3-510-65261-7.

- ^ Rudell, Paula J.; et al. (February 4, 2016). "Inside-out Flowers of Lacandonia braziliana...etc". PeerJ. 4 e1653. doi:10.7717/peerj.1653. PMC 4748704. PMID 26870611.

- ^ a b Lewis, C.T. & Short, C. (1879). A Latin dictionary founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b c Klein, E. (1971). A comprehensive etymological dictionary of the English language. Dealing with the origin of words and their sense development thus illustration the history of civilization and culture. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

- ^ Siebenhaar, F.J. (1850). Terminologisches Wörterbuch der medicinischen Wissenschaften. (Zweite Auflage). Leipzig: Arnoldische Buchhandlung.

- ^ a b Saalfeld, G.A.E.A. (1884). Tensaurus Italograecus. Ausführliches historisch-kritisches Wörterbuch der Griechischen Lehn- und Fremdwörter im Lateinischen. Wien: Druck und Verlag von Carl Gerold's Sohn, Buchhändler der Kaiserl. Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- ^ a b c d Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Goebel, K.E.v. (1969) [1905]. Organography of plants, especially of the Archegoniatae and Spermaphyta. Vol. Part 2 Special organography. New York: Hofner publishing company. pages 553–555

- ^ Rendle, A.B. (1925). The Classification of Flowering Plants. Cambridge University Press. p. 624. ISBN 978-0-521-06057-8.

cyclanthera.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Encyclopædia Britannica.com

- ^ Carr, Gerald (30 October 2005). "Flowering Plant Families". Vascular Plant Family. University of Hawaii Botany Department. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ William G. D'Arcy, Richard C. Keating (eds.) The Anther: Form, Function, and Phylogeny. Cambridge University Press, 1996 ISBN 9780521480635

- ^ Hickey, M.; King, C. (1997). Common Families of Flowering Plants. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57609-3.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rendle, Alfred Barton (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 553–573.

- Simpson, Michael G. (2011). "Androecium". Plant Systematics. Academic Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-08-051404-8. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- Weberling, Focko (1992). "1.5 The Androecium". Morphology of Flowers and Inflorescences (trans. Richard J. Pankhurst). CUP Archive. p. 93. ISBN 0-521-43832-2. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- "Obdiplostemony (obdiplostemonous)". Glossary for Vascular Plants. The William & Lynda Steere Herbarium, New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

External links

[edit]Stamen

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Basic Morphology

Definition and Function

The stamen is the fundamental unit of the androecium, the collective male reproductive structure in the flowers of angiosperms (flowering plants). Collectively, the stamens form the androecium, which is positioned in the third whorl of a typical flower and serves as the primary site for male reproductive processes.[7][8] The primary function of the stamen is to produce and release pollen grains, which are the male gametophytes containing sperm cells essential for sexual reproduction. Through pollination, these pollen grains are transferred to the stigma of the female reproductive organ (gynoecium), where they germinate and facilitate the fertilization of ovules, leading to seed and fruit development./10:_Module_7-_Plant_Diversity/10.10:_Angiosperms)[9] This process enables double fertilization unique to angiosperms, ensuring the propagation of the species. In bisexual flowers, stamens work in cooperation with the gynoecium to complete reproduction, distinguishing them from unisexual structures in separate male and female flowers.[7] The recognition of stamens as essential male organs emerged in botanical texts of the 18th century, notably through Carl Linnaeus's sexual system of classification, which emphasized their role in plant reproduction and seed production. Linnaeus formalized the understanding of stamens as analogous to male sexual organs, building on earlier observations and integrating them into systematic botany. Each stamen typically consists of a slender filament supporting an anther where pollen develops.[10][10]Core Components

The stamen, as the male reproductive organ of angiosperms, consists of two primary anatomical components: the filament and the anther. These structures work in concert to support pollen production and dispersal, with the filament providing structural elevation and nutrient supply to the anther, where pollen grains develop.[3][11] The filament is a slender, stalk-like extension that supports the anther at the apex of the stamen. It varies in length across species but is typically elongated to position the anther optimally within the flower, and it contains vascular tissue that facilitates the transport of nutrients and water to the developing anther.[12][13] During flower maturation, the filament undergoes elongation to elevate the anther, aiding in effective pollen dispersal by exposing it to pollinators or wind.[14][15] The anther, located at the distal end of the filament, is a bilobed structure that houses the microsporangia, or pollen sacs, responsible for pollen production. Each lobe contains two thecae, making the anther tetrasporangiate in most angiosperms, with connective tissue linking the lobes and extending vascular supply from the filament.[16][1] This organization ensures efficient microspore development within the pollen sacs, which are lined by nutritive tapetal tissue.[17]Etymology and Terminology

Etymology

The term "stamen" originates from the Latin stāmen, referring to the upright warp thread in a loom, derived from the verb stāre, meaning "to stand." This etymology aptly captures the slender, erect, thread-like filament that supports the pollen-bearing anther in flowers, evoking the vertical threads used in weaving.[18][19][20] The Latin word shares roots with Ancient Greek stḗmōn, denoting the warp in weaving and implying something standing upright, as well as stêma, a term glossed by the lexicographer Hesychius for a plant part. In classical Greek botany, such as in Theophrastus's Enquiry into Plants (c. 300 BCE), these thread-like structures were recognized as the male reproductive organs of flowers—responsible for producing what we now know as pollen—but lacked a specific name like "stamen" and were simply described as the "male parts" or components involved in seed formation alongside female elements.[21][22][23] By the 17th century, the term entered English botanical literature directly from Latin, with the earliest recorded use in 1650, often contrasted with vague descriptions in earlier herbals that likened flower parts to animal genitalia without precise nomenclature. It was mediated through Old French estamine (modern étamine, the standard French term for stamen), originally denoting a fine woolen cloth woven from threads, ultimately from Latin stamineus ("made of threads"). Carl Linnaeus further entrenched "stamen" in botanical taxonomy through his 1735 Systema Naturae, where he classified plants into classes based primarily on the number and arrangement of stamens, elevating the term's centrality in scientific descriptions of the androecium.[20][18][24][25]Key Anatomical Terms

In stamen anatomy, the androecium refers to the collective term for all stamens within a single flower, representing the male reproductive organs as a whole.[26][27] The theca denotes one half of an anther lobe, consisting of two microsporangia that house developing pollen grains.[28][29] The connective is the specialized tissue that links the thecae to the filament, often extending between the anther lobes; it may be continuous, spanning the full length, or adnate, meaning fused along part of its surface to surrounding structures.[26][27] Key terms describing anther attachment to the filament include basifixed, where the anther is affixed at its base, and dorsifixed, where attachment occurs along the dorsal surface.[30][26] For stamen arrangement, diplostemonous indicates stamens organized in two distinct whorls, with the outer whorl alternating opposite the petals.[26][30] Botanical nomenclature for stamens encompasses over 20 specialized terms to describe variations in fusion and position, such as epipetalous, where filaments are adnate to the petals for part or all of their length.[27][30] These terms standardize descriptions across angiosperm diversity, building on core components like the filament that supports the anther.[26]Structural Variations

Attachment and Arrangement

Stamens exhibit diverse modes of attachment within the flower, influencing their positioning relative to other floral organs. In hypogynous flowers, the stamens are attached to the receptacle below the gynoecium, positioning the ovary as superior and allowing free access to pollinators.[31] This configuration is common in many basal angiosperms and promotes efficient pollen dispersal. In contrast, epipetalous attachment occurs when the filaments are adnate to the corolla, often integrating the androecium closely with the petals for coordinated movement during pollination, as observed in families like Solanaceae.[28] Additionally, in certain species such as Cryptostegia and Calotropis, stamens are fused with the gynoecium, creating a unified reproductive structure that enhances pollen transfer mechanisms.[32] The filament, as the slender stalk of the stamen, connects the anther to these attachment sites, facilitating anther positioning. Staminal arrangements vary significantly, reflecting evolutionary adaptations for pollination. The haplostemonous condition features a single whorl of stamens alternating with the petals, promoting a simple, radial symmetry in flowers like those of Ipomoea.[33] In obdiplostemonous arrangements, stamens occur in two whorls, with the outer whorl positioned opposite the petals and the inner whorl opposite the sepals, a pattern that optimizes spatial separation for pollen presentation in families such as Simaroubaceae.[34] A specialized example is the tetradynamous arrangement in Brassicaceae, where the four long inner stamens alternate with the petals and the two short outer stamens align with the sepals, aiding in directed pollinator contact.[35] Fusion among stamens further diversifies their configuration, often forming cohesive units that protect or direct pollen. Free stamens remain distinct, allowing independent movement, whereas monadelphous fusion unites all filaments into a single tube encircling the style, as in many Malvaceae species.[36] Polyadelphous fusion involves the filaments coalescing into multiple bundles, providing structural support while maintaining partial independence, evident in families like Euphorbiaceae.[36] In Caryophyllaceae, the stamens form a pseudanthium-like cluster, connected basally in a short androecial tube that surrounds the ovary, enhancing collective pollen exposure.[37]Size, Number, and Fusion

Stamens in angiosperms exhibit considerable variation in number, ranging from a single stamen in diminutive monocots such as Wolffia species (duckweeds) to numerous stamens, often exceeding 100, in primitive families like Magnoliaceae.[38][39] In Magnoliaceae, these stamens are typically free and spirally arranged on an elongated receptacle, reflecting an ancestral condition with high pollen production potential.[39] Many Ranunculaceae display indefinite stamen numbers, with polyandrous arrangements that can include 10 to over 100 stamens spirally inserted, allowing flexibility in floral resource allocation.[40][41] Size extremes further highlight stamen diversity, with the smallest stamens measuring approximately 0.1 mm in Wolffia, aligning with the plant's overall frond size of less than 1 mm and its reduced floral morphology featuring a single stamen emerging from a lateral cavity.[42][43] At the opposite end, filaments can become exceptionally elongated, reaching up to several centimeters in vining species like certain Passiflora (passionflowers), where they extend pollen presentation beyond the corolla.[44] In Canna, anthers measure 0.7–1 cm in length, contributing to the flower's prominent display while the associated stamen filaments extend 4–5 cm.[45] Stamen fusion manifests in specialized forms across taxa, enhancing reproductive efficiency. In orchids, stamens fuse with the gynoecium to form a gynandrium, a central column that unites male and female organs for precise pollinator interaction.[46] Similarly, in Araceae, a synandrium arises from the cohesion of anthers from multiple male flowers, creating a compact structure on the spadix that facilitates collective pollen release.[47] An evolutionary trend toward stamen reduction in number and size is evident in wind-pollinated angiosperms, where simplified androecia with fewer, less ornate stamens optimize pollen dispersal by air currents over biotic vectors.[48][49]Development and Pollen Production

Microsporogenesis

Microsporogenesis is the initial phase of male gametophyte development in angiosperms, occurring within the microsporangia of the anther in the stamen. Diploid microspore mother cells, also known as pollen mother cells or microsporocytes, undergo meiosis to produce four haploid microspores arranged in a tetrad. This process begins with the enlargement of microspore mother cells surrounded by a callose wall, followed by two meiotic divisions: meiosis I reduces the chromosome number, and meiosis II separates the sister chromatids, resulting in the tetrad formation enclosed in a callosic envelope.[50][51] The anther's wall layers play crucial supportive roles during microsporogenesis. The tapetum, the innermost layer, provides nutrients, enzymes such as callase for degrading callosic walls to release individual microspores, and precursors for pollen wall formation, ultimately degenerating to contribute to the pollen coat. The endothecium, located external to the tapetum, offers structural integrity to the developing locules and later facilitates anther opening, though its primary support here is mechanical during early stages. These layers ensure the microspores are nourished and properly isolated post-tetrad stage.[52][50] Following microsporogenesis, microgametogenesis proceeds with the mitotic development of each microspore into a mature pollen grain. The first mitotic division is asymmetric, producing a large vegetative cell and a smaller generative cell enclosed within it; this is known as pollen mitosis I. In many species, the generative cell then undergoes a second mitosis (pollen mitosis II) to form two sperm cells, resulting in a tricellular pollen grain consisting of one vegetative cell and two sperm cells. However, the majority of angiosperm species—approximately 70%—disperse bicellular pollen, where the second division occurs after pollination on the stigma, with tricellular pollen more common in lineages like the Poaceae and some basal groups showing variations.[50][53]Anther Maturation and Dehiscence

During anther maturation, the tapetum undergoes programmed cell death (PCD), degenerating to release nutrients and enzymes essential for pollen wall formation and microspore development.[54] This degeneration typically occurs progressively from the tetrad stage through the vacuolate pollen stage, culminating in complete tapetal breakdown by the time pollen grains are fully mature.[55] Concurrently, the endothecium develops secondary wall thickenings composed of lignified fibrous bands, which enable hygroscopic expansion and contraction in response to humidity changes, facilitating the mechanical force required for anther opening.[56] These processes are coordinated with pollen maturation, ensuring that structural changes in the anther wall align with the readiness of pollen for release.[57] Anther dehiscence, the process of anther splitting to expose pollen, most commonly occurs via longitudinal slits along the suture of the thecae, representing the ancestral and predominant mechanism in angiosperms.[28] Alternative modes include poricidal dehiscence through apical pores, as seen in the Ericaceae family (heaths), where pollen is released from pore-like openings at the anther tips.[58] Less frequently, dehiscence involves valvular mechanisms, such as short terminal slits or pore-like valves, observed across various families and contributing to specialized pollination strategies.[59] In all cases, dehiscence is driven by the differential expansion of the endothecium and degeneration of internal layers, creating tension that ruptures the epidermis.[60] In certain angiosperms, such as orchids (Orchidaceae) and milkweeds (Asclepiadoideae within Apocynaceae), pollen grains aggregate into compact masses called pollinia rather than dispersing individually, adapting dehiscence for precise pollinator attachment.[61] These pollinia form within modified anthers and are often connected to elastic caudicles—stalk-like structures derived from tapetal or connective tissue—that extend from the pollinium to a sticky viscidium, enabling the entire mass to be removed and transferred intact during pollination.[62] This aggregation minimizes pollen waste and enhances delivery efficiency in these lineages.[63] Hormonal regulation orchestrates anther dehiscence, with abscisic acid (ABA) promoting the process by influencing water relations and lignification in the endothecium, while auxin signaling modulates endothecial development and jasmonic acid biosynthesis to ensure timely splitting.[64] Recent studies have highlighted auxin's role in hydraulic dynamics during dehiscence; for instance, 2024 research demonstrates that auxin-responsive genes accelerate lignification in the endothecium, generating the mechanical tension needed for rupture through regulated water loss and cell wall reinforcement.[65] These findings underscore auxin's integration with dehydration signals, bridging hormonal and biophysical mechanisms in anther maturation.[66]Role in Plant Reproduction

Pollination Mechanisms

Stamens play a central role in facilitating pollen transfer from anthers to stigmas in angiosperms, primarily through adaptations that exploit biotic pollinators such as insects or abiotic agents like wind. In approximately 90% of angiosperm species, pollination is animal-mediated, with stamens positioned to deposit pollen on the bodies of visiting pollinators for subsequent transfer to conspecific flowers.[67] This mechanism enhances reproductive success by promoting efficient cross-pollination, while the remaining species rely on wind or other abiotic vectors where stamens are structurally modified for passive dispersal.[49] In biotic pollination, anther positioning is crucial for precise pollen deposition. For instance, in buzz-pollinated flowers of the Solanaceae family, such as tomatoes, filaments bend and vibrate in response to bee-generated thoracic vibrations, causing poricidal anthers to release pollen explosively onto the insect's body.[68] This thigmonastic movement ensures targeted pollen placement, often near the pollinator's legs or abdomen, facilitating transfer to the stigma of another flower. Adaptations like ultraviolet nectar guides on petals near the stamens further attract insects by directing them toward reproductive structures, increasing contact with anthers and enhancing pollination efficiency.[69] In contrast, wind-pollinated species feature exposed, pendulous stamens with lightweight anthers that dangle on elongated filaments, allowing pollen to be easily carried by air currents without reliance on animal vectors.[70] Stamens also contribute to distinguishing self- from cross-pollination, often promoting outcrossing to avoid inbreeding depression. Heterostyly, a common polymorphism in families like Boraginaceae and Primulaceae, involves floral morphs with reciprocal differences in stamen lengths—short-styled plants have long stamens, and long-styled plants have short stamens—ensuring that pollen from one morph is deposited on a pollinator's body part that aligns with the complementary stigma of the opposite morph.[71] This reciprocal positioning maximizes legitimate cross-pollen transfer while minimizing self-pollen deposition. Recent studies highlight the vulnerability of these pollinator-dependent mechanisms to climate change; for example, extreme weather events in 2025 have been shown to disrupt nectar availability and pollinator behavior.[72] A global meta-analysis indicates that threatened species exhibit 26% higher levels of pollen limitation than non-threatened species.[73]Integration with Flower Structure

In bisexual flowers, the stamens are typically arranged in one or more whorls surrounding the central gynoecium, positioning the anthers in close proximity to the stigma to enable efficient pollen transfer and potential self-pollination within the same flower. This structural integration enhances reproductive efficiency by minimizing the distance pollen must travel, as seen in many angiosperms where the androecium forms a protective and functional enclosure around the pistil. For instance, in tomato flowers, the ten stamens fuse into a cone that envelops the gynoecium, further optimizing pollen dispersal during anther dehiscence.[3][74] In unisexual flowers, staminate flowers consist solely of stamens without pistils, while pistillate flowers feature a gynoecium but lack functional stamens, thereby separating male and female reproductive roles within the floral structure. This arrangement promotes cross-pollination by ensuring pollen production and reception occur in distinct flowers. Monoecious plants, such as corn (Zea mays), bear both staminate flowers (in the tassel) and pistillate flowers (in the ear) on the same individual, allowing for controlled genetic mixing while maintaining spatial separation of sexes. In contrast, dioecious species like willows (Salix spp.) produce staminate flowers exclusively on male plants and pistillate flowers on female plants, enforcing outcrossing through complete sexual dimorphism at the individual level.[75][76][77] Specialized floral integrations often involve fusions that adapt stamen positioning for enhanced reproductive success. In orchids, the fertile stamen(s) congenitally fuse with the style and stigma to form the gynostemium, a central column that unites male and female elements, thereby streamlining pollen deposition and collection by pollinators. This structure addresses the absence of discrete stamens in pistillate contexts by reconfiguring reproductive organs into a single functional unit, as observed across the Orchidaceae family. Additionally, some species feature sterile stamens known as staminodes, which, despite lacking pollen-producing capability, contribute to pollinator attraction through visual or nectar rewards, thereby supporting overall floral appeal without direct reproductive function.[78][79]Evolutionary and Comparative Biology

Evolutionary Origins

Stamens in angiosperms evolved from the microsporophylls of ancestral gymnosperms, representing a modification of leaf-like structures that bore microsporangia for pollen production.[80] This transition involved a reduction in size and complexity compared to gymnosperm microsporophylls, adapting the organs for enclosure within compact flowers rather than exposed cones.[80] Furthermore, stamens exhibit deep homology with the sporophylls and sporangia of ferns, where pollen sacs correspond to sporangia, but have specialized for producing pollen grains equipped with tubes for directed fertilization within enclosed carpels.[81] The earliest fossil evidence of stamens appears in early angiosperms around 140 million years ago during the Early Cretaceous, with well-preserved examples in Archaefructus liaoningensis dated to approximately 125 million years ago, featuring elongated stems bearing stamens alongside carpels in a pre-floral arrangement.[82] These fossils indicate that stamens were integral to the initial radiation of angiosperms, transitioning from gymnosperm-like open structures to integrated floral components.[83] Key evolutionary transitions included the enclosure of stamens within flowers featuring closed carpels, enhancing protection and efficiency in pollination.[84] Genetically, stamen identity is specified by the ABC model of floral development, where B-class MADS-box genes, such as APETALA3 and PISTILLATA, combine with C-class genes to determine stamen formation in the third whorl.[85] Recent genomic studies highlight the role of MADS-box gene duplications in land plants, predating angiosperms and facilitating the diversification of floral organs like stamens through neofunctionalization.[86]Diversity Across Angiosperms

Angiosperms exhibit remarkable diversity in stamen morphology and arrangement, reflecting adaptive radiations across major clades that enhance reproductive success in varied ecological niches. This variation includes differences in stamen number, fusion, anther type, and dehiscence mechanisms, often correlated with pollination strategies while maintaining core functions in pollen production and dispersal. Over 300,000 angiosperm species demonstrate stamen adaptations tied to pollination syndromes, such as elongated stamens in bird-pollinated flowers that facilitate precise pollen transfer during hovering visits.[87][88][89] In monocots, stamens typically number six, arranged in two whorls of three, a pattern evident in families like Liliaceae where this configuration supports efficient pollen release in open flowers. This arrangement represents a conserved trait among many monocot lineages, promoting symmetrical floral displays. However, extreme reduction occurs in orchids, where stamens are modified such that only one functional stamen remains, often fused with the gynoecium to form a pollinia-bearing column that enables specialized insect pollination. This reduction exemplifies adaptive modification within the clade, allowing for compact, precise pollen packaging.[90][91][92] Eudicots display even greater stamen diversity, with arrangements ranging from fixed numbers to indefinite spirals that accommodate varying pollinator interactions. In Rosaceae, stamens are often numerous (15 or more) and spirally arranged without a fixed count, forming a prominent central cluster that visually attracts pollinators and maximizes pollen availability in open, actinomorphic flowers. Similarly, poricidal anthers—characterized by terminal pores for pollen release—are prevalent in Ericales, particularly Ericaceae, where they facilitate buzz pollination by bees that vibrate the anthers to extract pollen, an adaptation enhancing efficiency in tubular corollas. These features underscore the clade's evolutionary flexibility in anther morphology to match diverse biotic vectors.[93][94] Among basal angiosperms, stamen structures retain primitive traits, as seen in Amborella trichopoda, the sister group to all other angiosperms, where anthers are tetrasporangiate with four microsporangia arranged in two thecae, supporting a basic developmental pattern that contrasts with more derived reductions in other lineages. Recent phylogenomic analyses, including 2023 genomic sequencing of related holoparasites, reveal extensive gene loss associated with stamen reduction in parasitic plants like Rafflesia, where stamens are highly modified into a synandrium or diaphragm-like structure, reflecting degenerative evolution in endoparasitic lifestyles that minimize host resource drain. These findings from high-throughput sequencing highlight how stamen loss correlates with loss of autotrophy and reliance on hosts, filling gaps in understanding reductive evolution across angiosperm parasites.[95][96]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/stamen