Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nkondi

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Kongo religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Nkondi (plural varies minkondi, zinkondi, or ninkondi)[1] are mystical statuettes made by the Kongo people of the Congo region. Nkondi are a subclass of minkisi that are considered aggressive.

Etymology

[edit]The name nkondi derives from the verb -konda, meaning "to hunt" and thus nkondi means "hunter" because they can hunt down and attack wrong-doers, witches, or enemies.[2]

Functions

[edit]

The primary function of a nkondi is to be the home of a spirit which can travel out from its base, hunt down and harm other people. Many nkondi were publicly held and were used to affirm oaths, or to protect villages and other locations from witches or evildoers. This is achieved by enlisting spiritual power through getting them to inhabit minkisi like nkondi.

The vocabulary of nkondi has connections with Kongo conceptions of witchcraft which are anchored in the belief that it is possible for humans to enroll spiritual forces to inflict harm on others through cursing them or causing them to have misfortune, accidents, or sickness. A frequently used expression for hammering in the nails into a nkondi is "koma nloka" (to attach or hammer in a curse) derives from two ancient Bantu roots *-kom- which includes hammering in its semantic field, and *-dog- which involves witchcraft and cursing.[3] "Kindoki", a term derived from the same root is widely associated with witchcraft, or effecting curses against others, but in fact refers to any action intended to enlist spirits to harm others. If exercised privately for selfish reasons, the use of this power is condemned as witchcraft, but if the power is used publicly by a village, tribe, political leaders, or as a protective measure by innocent people, however, it is not considered witchcraft.[4]

In the catechism of 1624, which probably reflects Christian language dating back to the now lost catechism of 1557, the verb koma was used to translate "to crucify."[5]

History

[edit]Because they are aggressive, many nkondi with human figures are carved with their hands raised, sometimes bearing weapons. The earliest representation of an nkisi in this pose can be seen in the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Kongo, designed around 1512 and illustrated between 1528 and 1541, where a broken "idol" is shown with this gesture at the base of the shield.[6] Nailed minkisi are not described in the literature left by missionaries or others in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries.

Wyatt MacGaffey, citing the work of the late seventeenth century Capuchin missionary Luca da Caltanisetta, noted that in his day, nganga sometimes banged minkisi together, perhaps a method of activating them, and nails, which MacGaffey contends were first being made at the time eventually replaced the metaphor.[7] Other scholars believe that the Portuguese missionaries brought images of Christ nailed to the cross and the martyr Saint Sebastian to the peoples of Central Africa, and these experts believe that this iconography maybe have influenced nkisi tradition.[8][9] MacGaffey, for his part, speaks against this interpretation, arguing that the concept of nailing is tied up with too many other concepts to be a simple misunderstanding of missionary teaching.[10]

Nkondi with nails were made at least as early as 1864, when the British Commodore A. P. Eardley Wilmont acquired one while suppressing Solongo (Soyo) piracy at the mouth of the Congo River, a piece that was the subject of a contemporary painting and is presently in the Royal Geographical Institute in London.[11] Another early description and illustration of a nailed nkondi (named Mabiala mu ndemba, and described as a "thief-finder") is found in the notes of the German expedition to Loango of 1873-76, so by that time the specific practice of nailing was well established.[12]

Construction

[edit]Nkondi, like other minkisi, are constructed by religious specialists, called nganga (plural zinganga or banganga). The nganga gathers materials, called nlongo (plural bilongo or milongo), which when assembled, will become the home of a spirit. Often these materials include a carved human figure into which the other bilongo are placed. The nganga then either becomes possessed with the spirit or places the finished nkondi in a graveyard or other place where spirits frequent. Once it is charged, the nkondi can then be handed over to the client. According to Kongo testimony of the early twentieth century, people drive nails into the figures as part of a petition for help, healing, or witness-particularly of contracts and pledges. The purpose of the nailing is to "awaken" and sometimes to "enrage" the nkisi to the task in hand.

Nkondi figures could be made in many forms, including pots or cauldrons, which were described and sometimes illustrated in early twentieth century Kikongo texts.[13] Those that used human images (kiteke) were most often nailed, and thus attracted collectors' attention and are better known today. Human figures ranged in size from small to life-size, and contained bilongo (singular longo; often translated as "medicine"), usually hidden by resin-fixed mirrors. Nkondi in the form of wooden figures were often carved with open cavities in their bodies for these substances. The most common place for storage was the belly, though such packs are also frequently placed on the head or in pouches surrounding the neck.

In most nkondi figures the eyes and medicine pack covers were reflective glass or mirrors, used for divination. The reflective surface enabled the nkisi to see in the spirit world in order to spy out its prey. Some nkondi figures were adorned with feathers. This goes along with the concept of the figures as being "of the above", and associates them with birds of prey.

The creation and use of nkondi figures was also a very important aspect to their success. Banganga often composed the nkondi figures at the edge of the village. The village was thought of as being similar to the human body. The idea that the edge and entrances needed to be protected from evil spirits occurred in both the human body and the village. When composing the minkisi, the nganga is often isolated in a hidden camp, away from the rest of the village. After the nkisi was built and the nganga had learned its proper use and the corresponding songs, he returned to the village covered in paint and behaving in a strange manner.

The unusual behavior was to illustrate the ngangas return to the land of the living. Prior to using the nkondi, the nganga recited specific invocations to awaken the nkondi and activate its powers. During their performances, banganga often painted themselves.[14] White circles around the eyes allowed them to see beyond the physical world and see the hidden sources of evil and illness. White stripes were painted on the participants. Often, the nganga was dressed similar to his nkondi. Banganga generally dressed in outfits that were vastly different than normal people. They wore ornate jewelry and often incorporated knots in their clothing. The knots were associated with a way of closing up or sealing of spiritual forces.

Nkondi in the diaspora

[edit]Aspects of Kongo spirituality made their way to the Americas via the Atlantic Slave trade. Many African diasporic spiritual traditions, such as Hoodoo and Palo, incorporate such aspects into their customs. Robert Farris Thompson, an American art historian has been particularly diligent, and influential in identifying Kongo influences in the African descended population of the Americas.[15][16]

Nkondi in contemporary art

[edit]European art collectors were interested in nkondi, especially the nailed ones, when they were reported back in the publications of the German Loango Expedition, which brought a good number of them back to Europe. Robert Visser, a German trader and diplomat also collected a great many examples for German museums, particularly in Berlin and Stuttgart. Many were purchased, others confiscated or removed by colonial authorities, and often found their way to museums, but many also remain in private hands.

More recently, artists have worked with the concept and visual imagery of nkondi to produce new works inspired by nkondi. African American artist Renee Stout's "Fetish no. 2 Archived 2012-04-14 at the Wayback Machine" first exhibited in 1988 is perhaps the most famous of these, a life sized statue cast from Stout's own body with the glass eye features and a few nails reminiscent of nkondi. Stout's work was the subject of a major exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution's Museum of African Art, featuring her various nkisi pieces with commentary by anthropologist Wyatt MacGaffey.[17]

In her mixed media composition "Intertexuality Vol. 1", African American artist Stephanie Dinkins disposed of the human figure of the nkondi but included the nails and the replaced the mirror with a video screen showing a 3-minute presentation, in an exhibition entitled "Voodoo Show: Kongo Criollo" in 1997.[18]

In her performance piece Destierro (Displacement) (first performed in Cuba and the US, 1998–99), Cuban artist Tania Bruguera dressed in a special suit made to resemble a nailed nkondi, and then, after remaining still for some hours, went around looking for those who had broken promises. She performed this piece also at the exhibit "Transfigured Worlds" (28 January-11 April 2010) at the Neuberger Museum of Art (New York).[19]

African American artist Kara Walker featured two nkondi figures in her silhouette piece "Endless Conundrum, an African Anonymous Adventure" in 2001, and frequently re-exhibited.[20] In her self-curated show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2006, Walker also used an nkisi, probably nkondi as a central motif for the show "Kara Walker at the Met: After the Deluge."[21]

African American artist Dread Scott (Scott Tyler) exhibited an African featured toy doll as a nkondi, with bullets serving as nails, at the Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art (Newark, NJ) in 2006-2007 in the three person show "But I Was Cool".[22]

In African American artist Karen Seneferu's multi-media sculptures, "Techno-Kisi I" and "Techno-Kisi II" both based on a nkondi with rounded nails but she included elements of modern communications technology such as slide shows or iPods to replace the traditionally mirrored eyes and belly. Her work was originally commissioned by the California African American Museum and shown also at the Skirball Cultural Center in 2010.[23]

South African Artist Michael MacGarry exhibited “ivory sculptures referring to Nkondi sculptures as well as the catastrophic aftermath of war," in the exhibition, "Contested Terrain" at the Tate Gallery, London, in August, 2011.[24]

American artist Justin Par adapted the aesthetic and philosophy of Nkisi Nkondi into three sculptures entitled 'Nkondi A', 'Nkondi B', and 'Nkondi C', using nails salvaged from utility poles, to create miniature architectural landscapes, in a solo exhibition entitled "Reliquum", at the Center for Visual Arts, in Greensboro, NC, 2012.

In his 2014 solo exhibition, 'AniMystikAktivist,' at the Goodman Gallery, Cape Town (13 December 2014 - 17 January 2015), South African artist Andrew Lamprecht presented a nkondi figure in modern form and drew attention to the potential Christian origins in the Kingdom of Kongo of the form.[25]

In a 2017 exhibit "The Prophet’s Library", African American artist Wesley Clark displayed "Doing for Self", a nkondi interpretation of the American flag. To Clark, this piece promotes reconciliation between the drifting spirituality and tradition of African diaspora and the injustice experienced in African American history.[26]

Nkondi in film

[edit]The 2006 film The Promise Keeper revolves around a life-sized Nkondi figure. In the film the nails represent promises made by those who hammered them into the figure, and the object comes to life at night to punish those who break the promises.[27]

Bibliography

[edit]- Bassani, Ezio (1977). "Kongo Nail Fetishes from the Chiloango River Area," African Arts 10: 36-40

- Doutreloux, A. (1961). "Magie Yombe," Zaire 15: 45-57.

- Dupré, Marie-Claude (1975). "Les système des forces nkisi chez le Kongo d'après le troisième volume de K. Laman," Africa 45: 12-28.

- Fromont, Cécile. "From Catholic Kingdom to the Heart of Darkness" in The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo. Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

- Janzen, John and Wyatt MacGaffey (1974). An Anthology of Kongo Religion Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press.

- Laman, Karl (1953–68). The Kongo 4 volumes, Uppsala: Studia Ethnografica Uppsaliensia.

- Lehuard, Raoul. (1980). Fétiches à clou a Bas-Zaire. Arnouville.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt, and John Janzen (1974). "Nkisi Figures of the BaKongo," African Arts 7: 87-89.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1977). "Fetishism Revisted: Kongo nkisi in Sociological Perspective." Africa 47: 140-152.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1988). "Complexity, Astonishment and Power: The Visual Vocabulary of Kongo Minkisi" Journal of Southern African Studies14: 188-204.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt, ed. and transl. (1991), Art and Healing of the Bakongo Commented Upon by Themselves Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt. "The Eyes of Understanding: Kongo Minkisi," in Wyatt MacGaffey and M. Harris, eds, Astonishment and Power Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 21–103.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (1998). "'Magic, or as we usually say 'Art': A Framework for Comparing African and European Art," in Enid Schildkrout and Curtis Keim, eds. The Scramble for Art in Central Africa. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 217–235.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt (2000). Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Vanhee, Hein (2000). "Agents of Order and Disorder: Kongo Minkisi," in Karel Arnaut, ed. Revisions: New Perspectives on African Collections of the Horniman Museum. London and Coimbra, pp. 89–106.

- Van Wing, Joseph (1959). Etudes Bakongo Brussels: Descleė de Brouwer.

- Volavkova, Zdenka (1972). "Nkisi Figures of the Lower Congo" African Arts 5: 52-89.

References

[edit]- ^ "Bakongo Nkondi Nail Fetish - RAND AFRICAN ART". www.randafricanart.com.

- ^ "Nail figure (nkisi nkondi) / Artist Unknown, Vili Peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo". University of Michigan Library. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Retrieved 8 July 2025.

- ^ Vansina, Jan (1990). Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa. Currey. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-85255-074-8.

- ^ Bockie, Simon (1993). Death and the Invisible Powers: The World of Kongo Belief. Indiana University Press. pp. 40–66. ISBN 978-0-253-31564-9.

- ^ Marcos Jorge, ed. Mateus Cardoso, ed. Doutrina Cristãa (Lisbon, 1624) Modern edition with French translation, ed. François Bontinck and D. Ndembi Nsasi (Brussels, 1978).

- ^ Fromont, Cécile (2011). "Under the sign of the cross in the kingdom of Kongo: Religious conversion and visual correlation in early modern Central Africa". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. 59–60 (59/60): 109–123. doi:10.1086/RESvn1ms23647785. ISSN 0277-1322. JSTOR 23647785.

- ^ Wyatt MacGaffey, Kongo Political Culture': The Conceptual Challenge of the particular (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), p. 99

- ^ Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art:Guide to the Collection. London, UK: GILES. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5. Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ^ Zdenka Volavka, "The Nkisi of Lower Zaire,"African Arts 5 (1972): 52-89.

- ^ MacGaffey, Kongo Political Culture p. 99.

- ^ Wyatt MacGaffey, "Commodore Wilmont Encounters Kongo Art 1865," African Arts (Summer, 2010): 52-54.

- ^ Beatrix Heintze, ed. Eduard Peuchël-Loesche, Tagbücher von der Loango Küste (Zentral-Afrika) (24.2.1875-5.5.1876)(Frankfurt-am-Main, 2011) entry of 1 April 1875, illustrated in Abb 8.

- ^ MacGaffey, Kongo Political Culture, pp. 100-101.

- ^ MacGaffey, Wyatt (1993). Astonishment & Power, The Eyes of Understanding: Kongo Minkisi. National Museum of African Art.

- ^ Thompson, Robert Farris (1984-08-12). Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-394-72369-3.

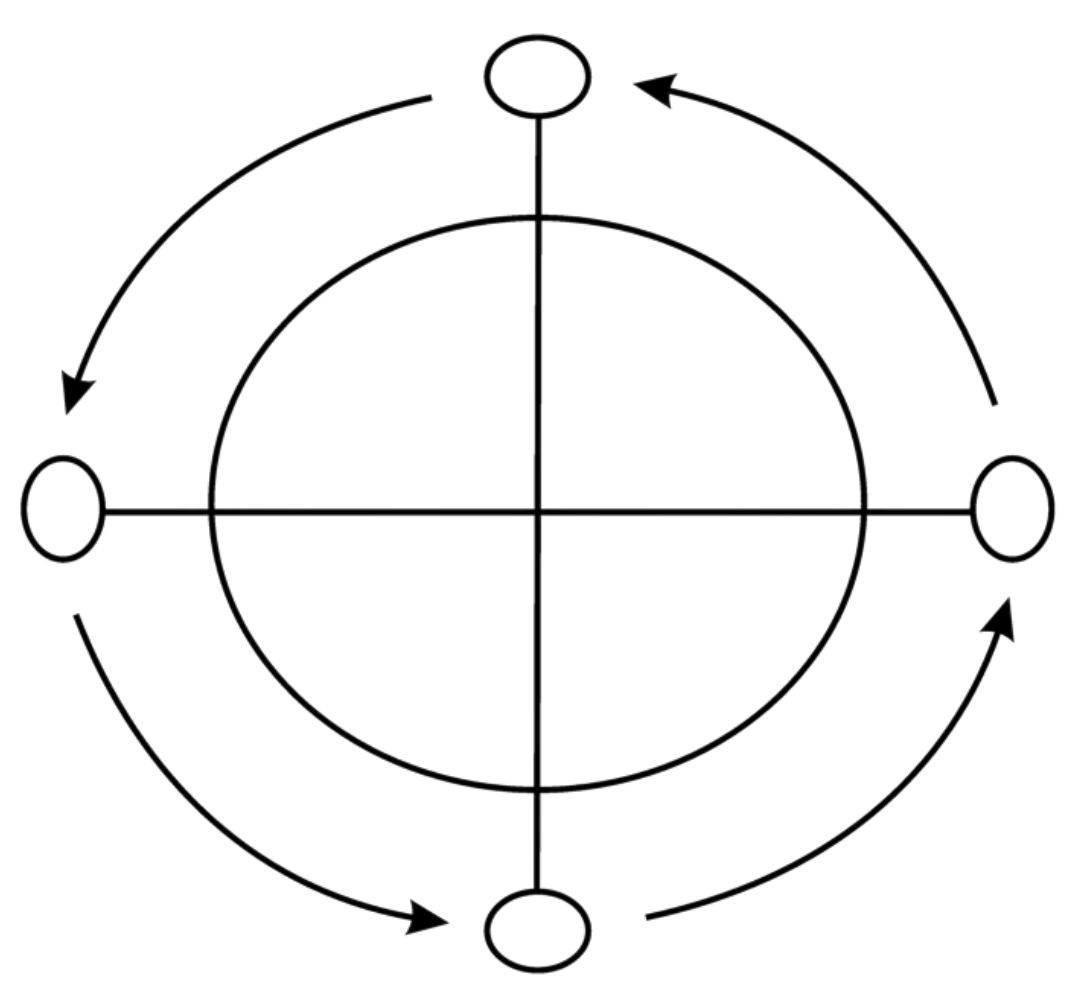

- ^ Thompson, Robert Farris; Cornet, Joseph (1981-08-30). The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1981.

- ^ Wyatt MacGaffey and M. Harris, eds, Astonishment and Power, (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993).

- ^ Stephanie Dinkins http://mysbfiles.stonybrook.edu/~sdinkins/Stephanie%20Dinkins/IntertextV1.html Archived 2012-09-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Neuberger Museum of Art Transformed Worlds Archived 2012-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love" Walker Art Center, Gallery Guide, http://media.walkerart.org/pdf/KWgallery_guide.pdf

- ^ Review by Cindi di Marzo, http://www.studio-international.co.uk/reports/kara_walker.asp Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Aavad.com". aavad.com.

- ^ Interview with Karen Senefuru, 2010 http://blog.sfmoma.org/2010/02/techno-kisi-interview-with-artist-karen-seneferu/

- ^ Tate Description, "Contested Terrain" http://www.tate.org.uk/modern/exhibitions/contestedterrains/room2.shtm[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Innovation Issue (13.3): Andrew Lamprecht In Conversation With Kendell Geers". April 9, 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-04-17.

- ^ Burd, Sara Lee (2017). "Wesley Clark: The Prophet's Library," Nashville Arts Magazine.

- ^ "The Promise Keeper". 10 February 2006 – via www.imdb.com.

External links

[edit]- Bakongo Nkondi Nail Fetish This site and its related links has many pictures and bibliography.

- En/Gendered Power: A nkisi from the Rockefeller Collection Archived 2019-02-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Brooklyn Museum: Standing Nkisi Figure

- Nkisi at the Art Institute of Chicago Archived 2018-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Nkondi at the Fowler Museum, UCLA, Los Angeles.

- Nkondi and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Nkondi at the Pitt-Rivers Museum Also contains useful text.

- The Promise Keeper on IMDb