Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Object–relational database

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2008) |

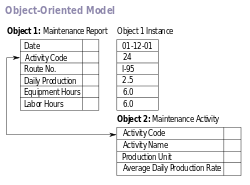

An object–relational database (ORD), or object–relational database management system (ORDBMS), is a database management system (DBMS) similar to a relational database, but with an object-oriented database model: objects, classes and inheritance are directly supported in database schemas and in the query language. Also, as with pure relational systems, it supports extension of the data model with custom data types and methods.

An object–relational database can be said to provide a middle ground between relational databases and object-oriented databases. In object–relational databases, the approach is essentially that of relational databases: the data resides in the database and is manipulated collectively with queries in a query language; at the other extreme are OODBMSes in which the database is essentially a persistent object store for software written in an object-oriented programming language, with an application programming interface API for storing and retrieving objects, and little or no specific support for querying.

Overview

[edit]The basic need of object–relational database arises from the fact that both Relational and Object database have their individual advantages and drawbacks. The isomorphism of the relational database system with a mathematical relation allows it to exploit many useful techniques and theorems from set theory. But these types of databases are not optimal for certain kinds of applications. An object oriented database model allows containers like sets and lists, arbitrary user-defined datatypes as well as nested objects. This brings commonality between the application type systems and database type systems which removes any issue of impedance mismatch. But object databases, unlike relational do not provide any mathematical base for their deep analysis.[2][3]

The basic goal for the object–relational database is to bridge the gap between relational databases and the object-oriented modeling techniques used in programming languages such as Java, C++, Visual Basic (.NET) or C#. However, a more popular alternative for achieving such a bridge is to use a standard relational database systems with some form of object–relational mapping (ORM) software. Whereas traditional RDBMS or SQL-DBMS products focused on the efficient management of data drawn from a limited set of data-types (defined by the relevant language standards), an object–relational DBMS allows software developers to integrate their own types and the methods that apply to them into the DBMS.

The ORDBMS (like ODBMS or OODBMS) is integrated with an object-oriented programming language. The characteristic properties of ORDBMS are 1) complex data, 2) type inheritance, and 3) object behavior. Complex data creation in most SQL ORDBMSs is based on preliminary schema definition via the user-defined type (UDT). Hierarchy within structured complex data offers an added property, type inheritance. That is, a structured type can have subtypes that reuse all of its attributes and contain additional attributes specific to the subtype. Another advantage, the object behavior, is related with access to the program objects. Such program objects must be storable and transportable for database processing, therefore they usually are named as persistent objects. Inside a database, all the relations with a persistent program object are relations with its object identifier (OID). All of these points can be addressed in a proper relational system, although the SQL standard and its implementations impose arbitrary restrictions and additional complexity[4][page needed]

In object-oriented programming (OOP), object behavior is described through the methods (object functions). The methods denoted by one name are distinguished by the type of their parameters and type of objects for which they attached (method signature). The OOP languages call this the polymorphism principle, which briefly is defined as "one interface, many implementations". Other OOP principles, inheritance and encapsulation, are related both to methods and attributes. Method inheritance is included in type inheritance. Encapsulation in OOP is a visibility degree declared, for example, through the public, private and protected access modifiers.

History

[edit]Object–relational database management systems grew out of research that occurred in the early 1990s. That research extended existing relational database concepts by adding object concepts. The researchers aimed to retain a declarative query-language based on predicate calculus as a central component of the architecture. Probably the most notable research project, Postgres (UC Berkeley), spawned two products tracing their lineage to that research: Illustra and PostgreSQL.

In the mid-1990s, early commercial products appeared. These included Illustra[5] (Illustra Information Systems, acquired by Informix Software, which was in turn acquired by International Business Machines (IBM), Omniscience (Omniscience Corporation, acquired by Oracle Corporation and became the original Oracle Lite), and UniSQL (UniSQL, Inc., acquired by KCOM Group). Ukrainian developer Ruslan Zasukhin, founder of Paradigma Software, Inc., developed and shipped the first version of Valentina database in the mid-1990s as a C++ software development kit (SDK). By the next decade, PostgreSQL had become a commercially viable database, and is the basis for several current products that maintain its ORDBMS features.

Computer scientists came to refer to these products as "object–relational database management systems" or ORDBMSs.[6]

Many of the ideas of early object–relational database efforts have largely become incorporated into SQL:1999 via structured types. In fact, any product that adheres to the object-oriented aspects of SQL:1999 could be described as an object–relational database management product. For example, IBM Db2, Oracle Database, and Microsoft SQL Server, make claims to support this technology and do so with varying degrees of success.

Comparison to RDBMS

[edit]An RDBMS might commonly involve SQL statements such as these:

CREATE TABLE Customers (

Id CHAR(12) NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

Surname VARCHAR(32) NOT NULL,

FirstName VARCHAR(32) NOT NULL,

DOB DATE NOT NULL # DOB: Date of Birth

);

SELECT InitCap(C.Surname) || ', ' || InitCap(C.FirstName)

FROM Customers C

WHERE Month(C.DOB) = Month(getdate())

AND Day(C.DOB) = Day(getdate())

Most current[update] SQL databases allow the crafting of custom functions, which would allow the query to appear as:

SELECT Formal(C.Id)

FROM Customers C

WHERE Birthday(C.DOB) = Today()

In an object–relational database, one might see something like this, with user-defined data-types and expressions such as BirthDay():

CREATE TABLE Customers (

Id Cust_Id NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

Name PersonName NOT NULL,

DOB DATE NOT NULL

);

SELECT Formal( C.Id )

FROM Customers C

WHERE BirthDay ( C.DOB ) = TODAY;

The object–relational model can offer another advantage in that the database can make use of the relationships between data to easily collect related records. In an address book application, an additional table would be added to the ones above to hold zero or more addresses for each customer. Using a traditional RDBMS, collecting information for both the user and their address requires a "join":

SELECT InitCap(C.Surname) || ', ' || InitCap(C.FirstName), A.city

FROM Customers C JOIN Addresses A ON A.Cust_Id=C.Id -- the join

WHERE A.city="New York"

The same query in an object–relational database appears more simply:

SELECT Formal( C.Name )

FROM Customers C

WHERE C.address.city="New York" -- the linkage is 'understood' by the ORDB

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Data Integration Glossary (PDF), US: Department of Transportation, August 2001, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-24, retrieved 2014-03-08

- ^ Frank Stajano (1995), A Gentle Introduction to Relational and Object Oriented Databases (PDF)

- ^ Naman Sogani (2015), Technical Paper Review (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04, retrieved 2015-10-05

- ^ Date, Christopher ‘Chris’ J.; Darwen, Hugh, The Third Manifesto

- ^ Stonebraker,. Michael with Moore, Dorothy. Object–Relational DBMSs: The Next Great Wave. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 1996. ISBN 1-55860-397-2.

- ^ There was, at the time, a dispute whether the term was coined by Michael Stonebraker of Illustra or Won Kim of UniSQL.

External links

[edit]- Savushkin, Sergey (2003), A Point of View on ORDBMS, archived from the original on 2012-03-01, retrieved 2012-07-21.

- JPA Performance Benchmark – comparison of Java JPA ORM Products (Hibernate, EclipseLink, OpenJPA, DataNucleus).

- PolePosition Benchmark – shows the performance trade-offs for solutions in the object–relational impedance mismatch context.

Object–relational database

View on Grokipediaperson_typ including name and address) and methods (e.g., procedures for validation), storable as column objects in relational tables or standalone row objects.[2] Inheritance enables type hierarchies, where subtypes (e.g., employee_typ extending person_typ) inherit and specialize properties, promoting reusability.[4] Collections such as varrays (fixed-size arrays) and nested tables support multi-valued attributes, while references (REFs) act as pointers for navigating relationships between objects without joins.[2] Additional capabilities include large object (LOB) support for binary data like images and videos, and extensibility through user-defined functions and access methods, making ORDBMS suitable for applications in geographic information systems, financial modeling, and multimedia management.[1][3]

Compared to pure relational databases, ORDBMS reduce development overhead by embedding business logic closer to data, improving query performance for complex scenarios (e.g., reducing processing time from hours to minutes in analytical tasks), though they introduce complexity in schema evolution and may require specialized skills.[3] In contrast to object-oriented databases, they retain SQL compatibility and ACID properties for transactional reliability, positioning ORDBMS as a hybrid solution for modern data-intensive environments.[4]

Fundamentals

Definition

An object-relational database management system (ORDBMS) is a database management system that extends the traditional relational data model—characterized by tables, rows, columns, and the Structured Query Language (SQL)—with object-oriented programming paradigms, including user-defined types, inheritance, encapsulation, polymorphism, and support for complex data structures such as collections and multimedia objects.[6][3] This integration allows for the representation of both simple scalar values and hierarchical, nested data within a unified framework, bridging the gap between structured relational storage and the flexibility of object models.[7] The hybrid nature of an ORDBMS lies in its seamless combination of relational operations, executed via extended SQL dialects (such as SQL3 standards), with object-handling extensions that enable the definition of custom types and methods associated with data.[6] For instance, it supports type hierarchies where subtypes inherit attributes and behaviors from supertypes, while maintaining the declarative querying efficiency of relational systems for both atomic and composite data types.[3] This design facilitates encapsulation, where data and associated operations are bundled into reusable objects, without abandoning the ACID properties and scalability inherent to relational architectures.[7] Fundamentally, ORDBMSs are engineered to overcome the limitations of pure relational databases in managing complex, real-world data scenarios—such as geographic information systems or CAD models—where hierarchical relationships and behavioral methods are prevalent, all while preserving the query optimization and data integrity benefits of the relational model.[3] By incorporating these object-oriented capabilities, ORDBMSs enable more intuitive modeling of application-specific domains directly in the database, reducing the impedance mismatch between object-oriented application code and underlying data storage.[6]Key Concepts

Object-relational databases integrate object-oriented principles into the relational model by supporting user-defined types (UDTs), which allow users to create custom data types that encapsulate both attributes and methods, extending the built-in SQL types such as integers or strings.[8] These UDTs enable the definition of complex entities, such as a "Point" type with attributes for x and y coordinates and methods for calculating distance, thereby facilitating more expressive data modeling within relational schemas.[9] A core feature is support for inheritance and polymorphism through type hierarchies, where subtypes inherit attributes and methods from supertypes, promoting code reuse and hierarchical organization of data types.[10] This allows polymorphic queries, such as selecting all shapes (e.g., circles or rectangles inheriting from a base "Shape" type) using a single query that operates on the supertype, without needing type-specific unions.[11] Encapsulation in object-relational systems bundles data attributes and associated operations (methods) within UDTs, controlling access through method invocations rather than direct attribute manipulation, which contrasts with the flat, attribute-only structure of traditional relational tables.[8] For instance, a UDT for an employee might include private salary data accessible only via a "computeBonus" method, ensuring data integrity and modularity.[9] To handle intricate relationships, object-relational databases incorporate complex data structures like arrays, multisets, and reference (REF) types, which go beyond simple foreign keys by allowing nested collections and direct object pointers.[9] Arrays store ordered sequences (e.g., an array of phone numbers for a contact), multisets permit unordered collections with duplicates (e.g., multiple tags per item), and REF types enable navigation between objects, such as linking a department REF to its employees. Object identifiers (OIDs) provide unique, system-generated handles for instances of objects, facilitating direct referencing and traversal of object graphs independent of primary keys.[10] In practice, OIDs underpin REF types, allowing efficient pointer-like access in queries, such as dereferencing a REF to retrieve a full object without joins.[12]Historical Development

Origins

In the late 1980s, the limitations of the relational model, originally proposed by E. F. Codd in 1970 for managing structured data through tables and relations, became increasingly apparent as applications demanded support for complex data types such as multimedia content and computer-aided design (CAD) models.[13] Relational databases, reliant on flat tabular structures, struggled to efficiently represent hierarchical or multifaceted objects, leading to the object-relational impedance mismatch—a conceptual gap between the object-oriented paradigms of emerging programming languages like C++, released in 1985, and the normalized, set-based nature of relational storage.[14] This mismatch complicated data persistence and retrieval in object-oriented applications, prompting researchers to explore extensions that could bridge the two worlds without abandoning the relational foundation's maturity in query optimization and transaction support. Early proposals for integrating object capabilities into relational systems emerged around 1989, with researchers like Won Kim advocating for query models that aligned object-oriented data structures with relational querying. Kim's work at the 1989 VLDB conference introduced a comprehensive query framework for object-oriented databases, emphasizing inheritance, encapsulation, and complex object navigation while drawing on SQL-like extensions to handle these features.[15] Similarly, Stanley Zdonik and colleagues at Brown University developed a query algebra in 1989 that synthesized relational operators with object identity and abstract data types, enabling extensible type systems within a relational algebra context to address the shortcomings in representing real-world entities like engineering designs. These foundational ideas positioned object-relational approaches as a pragmatic evolution, allowing developers to leverage object-oriented programming's expressiveness without fully migrating to nascent pure object databases. Initial prototypes exemplified this shift, notably the POSTGRES project at the University of California, Berkeley, initiated in 1986 under Michael Stonebraker as a successor to the Ingres relational system. POSTGRES introduced type extensibility, allowing users to define custom abstract data types and operators, alongside QUEL query language enhancements for handling complex objects—features that prefigured object-relational database management systems (ORDBMS) by supporting inheritance and methods within a relational framework.[16] By the early 1990s, this work had transitioned toward SQL compatibility, influencing broader adoption. Industry recognition of the object-relational paradigm gained momentum at the 1990 International Conference on Database Theory (ICDT), where sessions highlighted hybrid models as a compromise between relational scalability and object-oriented flexibility. Papers such as "A Relational Object Model" explored evolutionary paths from nested relational structures to object support, underscoring the paradigm's potential to manage diverse data like geospatial information without sacrificing ACID properties.[17] These discussions marked a pivotal acknowledgment of ORDBMS as a viable direction in database evolution.Evolution and Standards

The evolution of object-relational database management systems (ORDBMS) gained momentum in the late 1990s through formal standardization efforts that extended the relational model with object-oriented capabilities. The SQL:1999 standard, also known as SQL3, introduced key object-relational extensions, including user-defined structured types, methods associated with types, and single inheritance hierarchies for types, enabling more complex data modeling within SQL.[10][9] This standard was ratified by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) as ISO/IEC 9075:1999, with the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) adopting it later that year.[18][19] Subsequent revisions built upon these foundations, enhancing object-relational features while addressing emerging needs. SQL:2003, formalized as ISO/IEC 9075:2003, incorporated XML data integration capabilities that complemented structured types and reference (REF) types standardized earlier, allowing ORDBMS to handle semi-structured data more effectively.[20] SQL:2011 further advanced temporal data support, such as period specifications for time-based queries, which leveraged user-defined types (UDTs) and inheritance from prior standards to manage validity periods in relational tables.[19] ANSI and ISO continued to play central roles in refining UDTs and REF types across these updates, ensuring portability and consistency in object-relational implementations.[21] Key milestones in the 1990s and early 2000s highlighted the transition from proprietary extensions to standardized practices. Vendors like Oracle introduced object-relational capabilities through products such as the Oracle Universal Server in 1997 (released as Oracle8), which supported advanced data types and extensibility ahead of formal standards.[22] Similarly, Informix acquired the Illustra object-relational system in 1997, enhancing its Dynamic Server with support for complex data types and user-defined functions, contributing to commercial advancements in the field.[23] By the early 2000s, the focus shifted toward open standards, exemplified by PostgreSQL providing significant support for SQL:1999 features, including structured types, methods, and inheritance, in version 7.1 released in 2001, demonstrating practical adoption in an open-source environment.[24] As of 2025, object-relational standards remain foundational under the latest SQL:2023 (ISO/IEC 9075:2023), with no major overhauls to core features such as UDTs and inheritance since SQL:2016, though SQL:2023 includes enhancements like improved JSON support and property graph querying to address hybrid data needs.[25] Modern developments emphasize hybrid systems integrating ORDBMS with NoSQL elements, such as JSON support in SQL extensions, to address diverse data needs without supplanting established relational-object paradigms.[26]Architecture and Data Model

Core Components

The core architecture of an object-relational database management system (ORDBMS) is built upon a relational backbone that serves as the foundational structure for data storage and manipulation. Tables function as the primary storage units, with rows representing tuples that encapsulate both simple scalar values and references to complex objects, maintaining the tabular organization inherent to relational models.[22] An integrated SQL engine enables declarative querying, supporting operations such as joins across tables and full transaction management to ensure ACID properties—atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability—for reliable data processing.[3] This relational core provides the stability and efficiency of traditional relational database management systems (RDBMS) while allowing seamless integration of object-oriented extensions. The storage manager in an ORDBMS oversees the persistence of diverse data forms, accommodating both scalar types like integers and strings as well as object data such as user-defined structures. It employs efficient mechanisms like B-tree indexing to optimize access and retrieval for relational data, ensuring fast lookups and range queries on tuple attributes.[27] For object persistence, the manager supports advanced techniques including graph traversal to navigate relationships defined by references or inheritance, enabling the handling of interconnected data without compromising relational performance.[3] In systems like PostgreSQL, this is implemented through heap files and auxiliary structures for large objects, balancing storage efficiency with query speed.[28] Query optimization in an ORDBMS extends the capabilities of relational optimizers to process queries involving object features, generating execution plans that account for the added complexity of non-scalar data. It relies on cost-based planning algorithms to evaluate multiple paths, incorporating statistics on data distribution and index usage to minimize execution costs for operations like joins and aggregations.[29] Specifically, the optimizer addresses polymorphic queries—where method invocation depends on the actual object type—and inheritance-based operations by resolving types at runtime and selecting appropriate access methods, such as specialized indexes for user-defined types.[22] This ensures that object queries perform comparably to pure relational ones, as seen in Oracle's adaptive plans that adjust for varying data shapes.[22] Central to the ORDBMS architecture is the metadata repository, typically realized as a system catalog that maintains comprehensive schema information to support dynamic operations. This repository stores definitions for user-defined types (UDTs), including their attributes and associated methods, as well as details on inheritance hierarchies that define subtype-supertype relationships.[1] By enabling runtime type resolution and schema evolution, it allows the system to handle polymorphic behaviors and reference integrity without explicit user intervention, as exemplified in PostgreSQL's pg_catalog tables that track type dependencies and methods.[30] UDTs, as integrated components, rely on this catalog for seamless incorporation into relational tables.[3]Object-Relational Features

Object-relational database management systems (ORDBMS) extend the relational type system to support user-defined types (UDTs), also known as structured types, which encapsulate both data attributes and associated methods. These types are created using SQL Data Definition Language (DDL) statements, such asCREATE TYPE, allowing users to define complex data structures that go beyond primitive scalar types like NUMBER or VARCHAR2. For instance, a Point type can be defined with attributes for x and y coordinates (e.g., x NUMBER, y NUMBER) and a method to compute distance (e.g., distance(self Point, other Point) RETURNS NUMBER). This extensibility aligns with SQL:1999 standards, which introduced support for such structured types to model real-world entities more naturally within a relational framework. Implementation of these features varies across ORDBMS vendors, with full SQL:1999 compliance differing between systems like Oracle and PostgreSQL.[2][8]

In systems supporting them, such as Oracle, reference types, denoted as REF, serve as logical pointers to row objects, enabling navigation between related objects via object identifiers (OIDs). Collections, such as variable-length arrays (VARRAY) for ordered fixed-size sets or nested tables (TABLE or multiset types) for unordered variable-size collections, allow nesting of structured data within attributes. Navigation occurs through dereferencing paths, for example, querying table.row.ref.attribute to access linked object properties, or using operators like -> in SQL:1999 for concise pointer traversal (e.g., ss.beer()->name to retrieve a beer's name from a sales object). Other ORDBMS may use alternative mechanisms like foreign keys for relationships. These features facilitate modeling complex relationships and multi-valued attributes without excessive joins.[2][31][32]

Methods defined within structured types can be invoked directly in SQL Data Manipulation Language (DML) statements, promoting encapsulation by hiding implementation details while exposing behavior through queries. For example, the statement SELECT e.[salary](/page/Salary)() FROM employees e calls a salary() method on each employee object e, potentially computing dynamic values based on attributes like base pay and bonuses. Member methods operate on instance data, while static methods apply to the type itself; both support overriding in subtypes for polymorphism. This integration allows SQL to leverage object-oriented principles without abandoning declarative querying.[2][31]

Inheritance in ORDBMS is implemented through type hierarchies, where subtypes are defined UNDER a supertype using SQL:1999 syntax, inheriting attributes and methods while adding or overriding elements. Storage strategies include table-per-class, where each type has a dedicated object table (e.g., separate tables for Person and its Student subtype), or table-per-hierarchy, using a single supertype table to store all instances with a discriminator for subtypes. Query rewriting and dynamic dispatch enable subtype polymorphism; for instance, queries on the supertype return substitutable subtype rows, and functions like TREAT (e.g., TREAT(p AS student_typ).major) access subtype-specific attributes at runtime. This approach ensures transparent navigation across the hierarchy without manual union operations.[11][8][32]

Comparisons

With Relational Databases

Traditional relational database management systems (RDBMS) rely on a data model characterized by flat tables adhering to the first normal form (1NF), where attributes are atomic and primitive types such as integers or strings predominate, necessitating decomposition of complex entities into multiple relations and subsequent joins for reconstruction.[33] In contrast, object-relational database management systems (ORDBMS) extend this foundation by incorporating user-defined types (UDTs) that support structured and collection types, such as rows, arrays, and multisets, allowing nested relations and complex objects to be modeled within a single tuple without extensive normalization.[34] Furthermore, ORDBMS introduce inheritance hierarchies for types, enabling subtypes to inherit attributes and methods from supertypes, which facilitates richer schema designs for hierarchical data like personnel categories (e.g., aStudent type inheriting from Person).[34] This augmentation addresses the limitations of RDBMS in handling multifaceted entities, such as multimedia or spatial data, by providing an extended type system that blends relational normalization with object-oriented structuring.[35]

Both RDBMS and ORDBMS utilize SQL as their primary query language, ensuring continuity in declarative querying and set-based operations.[36] However, ORDBMS enhance SQL with object-oriented predicates and constructs, such as the IS OF operator for type checking (e.g., verifying if a row is an instance of a specific UDT) and dot notation for invoking user-defined methods directly in queries (e.g., SELECT e.give_raise(10%) FROM employees e).[34] These extensions, including support for collection-derived tables and polymorphic queries, allow complex object manipulations within the database, thereby reducing the need for application-layer code to transform relational results into object structures.[37]

A key distinction arises in application integration: RDBMS exacerbate the object-relational impedance mismatch by requiring object-oriented applications to flatten hierarchical objects into tabular rows and reconstruct them via object-relational mapping (ORM) tools, leading to inefficiencies in data serialization, identity management, and navigation.[38] ORDBMS mitigate this mismatch through native storage of complex objects via UDTs and references, enabling direct persistence and retrieval of object instances with preserved structure and behavior, thus streamlining development for object-oriented paradigms.[38]

Regarding standardization, RDBMS conform fully to the SQL-92 (SQL2) standard, which emphasizes core relational features like joins and integrity constraints without object extensions.[36] ORDBMS build upon this by partially adopting SQL:1999 (SQL3) features, such as UDTs, inheritance, and method bindings, though implementation varies due to optional modules and vendor-specific enhancements, resulting in incomplete uniformity across systems.[36] This evolutionary approach maintains backward compatibility while introducing object-relational capabilities, but partial adoption has led to interoperability challenges in multi-vendor environments.[36]