Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

B-tree

View on Wikipedia| B-tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Tree (data structure) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Invented | 1970[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Invented by | Rudolf Bayer, Edward M. McCreight | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Complexities in big O notation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In computer science, a B-tree is a self-balancing tree data structure that maintains sorted data and allows searches, sequential access, insertions, and deletions in logarithmic time. The B-tree generalizes the binary search tree, allowing for nodes with more than two children.[2]

By allowing more children under one node than a regular self-balancing binary search tree, the B-tree reduces the height of the tree, hence putting the data in fewer separate blocks. This is especially important for trees stored in secondary storage (e.g. disk drives), as these systems have relatively high latency and work with relatively large blocks of data, hence the B-tree's use in databases and file systems. This remains a major benefit when the tree is stored in memory, as modern computer systems heavily rely on CPU caches: compared to reading from the cache, reading from memory in the event of a cache miss also takes a long time.[3][4]

History

[edit]While working at Boeing Research Labs, Rudolf Bayer and Edward M. McCreight invented B-trees to efficiently manage index pages for large random-access files. The basic assumption was that indices would be so voluminous that only small chunks of the tree could fit in the main memory. Bayer and McCreight's paper Organization and maintenance of large ordered indices[1] was first circulated in July 1970 and later published in Acta Informatica.[5]

Bayer and McCreight never explained what, if anything, the B stands for; Boeing, balanced, between, broad, bushy, and Bayer have been suggested.[6][7][8] When asked "I want to know what B in B-Tree stands for," McCreight answered[7]:

Everybody does!

So you just have no idea what a lunchtime conversation can turn into. So there we were, Rudy and I, at lunch. We had to give the thing a name.... We were working for Boeing at the time, but we couldn't use the name without talking to the lawyers. So there's a B.

It has to do with Balance. There's another B.

Rudy was the senior author. Rudy (Bayer) was several years older than I am, and had ... many more publications than I did. So there's another B.

And so at the lunch table, we never did resolve whether there was one of those that made more sense than the rest.

What Rudy likes to say is, the more you think about what the B in B-Tree means, the better you understand B-Trees!

Definition

[edit]According to Knuth's definition, a B-tree of order m is a tree that satisfies the following properties:[9]

- Every node has at most m children.

- Every node, except for the root and the leaves, has at least ⌈m/2⌉ children.

- The root node has at least two children unless it is a leaf.

- All leaves appear on the same level.

- A non-leaf node with k children contains k−1 keys.

Each internal node's keys act as separation values that divide its subtrees. For example, if an internal node has 3 child nodes (or subtrees), then it must have 2 keys: a1 and a2. All values in the leftmost subtree will be less than a1, all values in the middle subtree will be between a1 and a2, and all values in the rightmost subtree will be greater than a2.

- Internal nodes

- Internal nodes (also known as inner nodes) are all nodes except for leaf nodes and the root node. They are usually represented as an ordered set of elements and child pointers. Every internal node contains a maximum of U children and a minimum of L children. Thus, the number of elements is always 1 less than the number of child pointers (the number of elements is between L−1 and U−1). U must be either 2L or 2L−1; therefore each internal node is at least half full. The relationship between U and L implies that two half-full nodes can be joined to make a legal node, and one full node can be split into two legal nodes (if there's room to push one element up into the parent). These properties make it possible to delete and insert new values into a B-tree while also adjusting the tree to preserve its properties.

- The root node

- The root node's number of children has the same upper limit as internal nodes but has no lower limit. For example, when there are fewer than L−1 elements in the entire tree, the root will be the only node in the tree with no children at all.

- Leaf nodes

- In Knuth's terminology, the "leaf" nodes are the actual data objects/chunks. The internal nodes that are one level above these leaves are what would be called the "leaves" by other authors: these nodes only store keys (at most m-1, and at least m/2-1 if they are not the root) and pointers (one for each key) to nodes carrying the data objects/chunks.

A B-tree of depth n+1 can hold about U times as many items as a B-tree of depth n, but the cost of search, insert, and delete operations grows with the depth of the tree. As with any balanced tree, the cost grows much more slowly than the number of elements.

Some balanced trees store values only at leaf nodes and use different kinds of nodes for leaf nodes and internal nodes. B-trees keep values in every node in the tree except leaf nodes.

Differences in terminology

[edit]The literature on B-trees is not uniform in its terminology.[10]

Bayer and McCreight (1972),[5] Comer (1979),[2] and others define the order of B-tree as the minimum number of keys in a non-root node. Folk and Zoellick[11] point out that terminology is ambiguous because the maximum number of keys is unclear. An order 3 B-tree might hold a maximum of 6 keys or a maximum of 7 keys. Knuth (1998) avoids the problem by defining the order to be the maximum number of children (which is one more than the maximum number of keys).[9]

The term leaf is also inconsistent. Bayer and McCreight (1972)[5] considered the leaf level to be the lowest level of keys, but Knuth considered the leaf level to be one level below the lowest keys.[11] There are many possible implementation choices. In some designs, the leaves may hold the entire data record; in other designs, the leaves may only hold pointers to the data record. Those choices are not fundamental to the idea of a B-tree.[12]

For simplicity, most authors assume there are a fixed number of keys that fit in a node. The basic assumption is that the key size and node size are both fixed. In practice, variable-length keys may be employed.[13]

Informal description

[edit]

Node structure

[edit]As with other trees, B-trees can be represented as a collection of three types of nodes: root, internal (a.k.a. interior), and leaf.

Note the following variable definitions:

- K : Maximum number of potential search keys for each node in a B-tree. (this value is constant over the entire tree).

- pti : The pointer to a child node that starts a sub-tree.

- pri : The pointer to a record that stores the data.

- ki : The search key at the zero-based node index i.

In B-trees, the following properties are maintained for these nodes:

- If ki exists in any node in a B-tree, then ki-1 exists in that node where .

- All leaf nodes have the same number of ancestors (i.e., they are all at the same depth).

Each internal node in a B-tree has the following format:

| pt0 | k0 | pt1 | pr0 | k1 | pt2 | pr1 | ... | kK-1 | ptK | prK-1 |

|---|

| pt0 | pti | pri | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| when | k0 exists | ki-1 and ki exist |

ki-1 exists, and ki does not exist |

ki-1 and ki do not exist |

ki exists | ki does not exist | |

| Pt : Points to subtree in which all search keys |

Pt < k0 | ki-1 < Pt < ki | Pt > ki-1 | pti is empty. | Points to a record with a value Pr = ki |

pri is empty. | |

Each leaf node in a B-tree has the following format:

| pr0 | k0 | pr1 | k1 | ... | prK-1 | kK-1 |

|---|

| pri when ki exists | pri when ki does not exist |

|---|---|

| Points to a record with a value equal to ki. | Here, pri is empty. |

The node bounds are summarized in the table below:

| Node type | number of keys |

number of child nodes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Min | Max | |

| Root node when it is a leaf node | 0 | K | 0 | 0 |

| Root node when it is an internal node | 1 | K | 2[14] | |

| Internal node | K | |||

| Leaf node | K | 0 | 0 | |

Insertion and deletion

[edit]To maintain the predefined range of child nodes, internal nodes may be joined or split.

Usually, the number of keys is chosen to vary between d and , where d is the minimum number of keys, and is the minimum degree or branching factor of the tree. The factor of 2 will guarantee that nodes can be split or combined.

If an internal node has keys, then adding a key to that node can be accomplished by splitting the hypothetical key node into two d key nodes and moving the key that would have been in the middle to the parent node. Each split node has the required minimum number of keys. Similarly, if an internal node and its neighbor each have d keys, then a key may be deleted from the internal node by combining it with its neighbor. Deleting the key would make the internal node have keys; joining the neighbor would add d keys plus one more key brought down from the neighbor's parent. The result is an entirely full node of keys.

A B-tree is kept balanced after insertion by splitting a would-be overfilled node, of keys, into two d-key siblings and inserting the mid-value key into the parent. Depth only increases when the root is split, maintaining balance. Similarly, a B-tree is kept balanced after deletion by merging or redistributing keys among siblings to maintain the d-key minimum for non-root nodes. A merger reduces the number of keys in the parent potentially forcing it to merge or redistribute keys with its siblings, and so on. The only change in depth occurs when the root has two children, of d and (transitionally) keys, in which case the two siblings and parent are merged, reducing the depth by one.

This depth will increase slowly as elements are added to the tree, but an increase in the overall depth is infrequent, and results in all leaf nodes being one more node farther away from the root.

Comparison to other trees

[edit]Because a range of child nodes is permitted, B-trees do not need re-balancing as frequently as other self-balancing search trees but may waste some space since nodes are not entirely full.

B-trees have substantial advantages over alternative implementations when the time to access the data of a node greatly exceeds the time spent processing that data, because the cost of accessing the node may then be amortized over multiple operations within the node. This usually occurs when the node data are stored in secondary storage, such as disk drives. By maximizing the number of keys within each internal node, the height of the tree decreases and the number of expensive node accesses is reduced. In addition, rebalancing of the tree occurs less frequently. The maximum number of child nodes depends on the information that must be stored for each child node and the size of a full disk block or an analogous size in secondary storage. While 2–3 B-trees are easier to explain, practical B-trees using secondary storage need a large number of child nodes to improve performance.

Variants

[edit]The term B-tree may refer to a specific design or a general class of designs. In the narrow sense, a B-tree stores keys in its internal nodes but need not store those keys in the records at the leaves. The general class includes variations such as the B+ tree, the B* tree and the B*+ tree.

- In the B+ tree, the internal nodes do not store any pointers to records; thus all pointers to records are stored in the leaf nodes. In addition, a leaf node may include a pointer to the next leaf node to speed up sequential access.[2] Because B+ tree internal nodes have fewer pointers, each node can hold more keys, causing the tree to be shallower and thus faster to search.

- The B* tree balances more neighboring internal nodes to keep the internal nodes more densely packed.[2] This variant ensures non-root nodes are at least 2/3 full instead of 1/2.[15] As the most costly part of operation of inserting the node in B-tree is splitting the node, B*-trees are created to postpone splitting operation as long as they can.[16] To maintain this, instead of immediately splitting up a node when it gets full, its keys are shared with a node next to it. This spill operation is less costly to do than split because it requires only shifting the keys between existing nodes, not allocating memory for a new one.[16] For inserting, first it is checked whether the node has some free space in it, and if so, the new key is just inserted in the node. However, if the node is full (it has m − 1 keys, where m is the order of the tree as the maximum number of pointers to subtrees from one node), it needs to be checked whether the right sibling exists and has some free space. If the right sibling has j < m − 1 keys, then keys are redistributed between the two sibling nodes as evenly as possible. For this purpose, m − 1 keys from the current node, the new key inserted, one key from the parent node and j keys from the sibling node are seen as an ordered array of m + j + 1 keys. The array becomes split by half so that ⌊(m + j + 1)/2⌋ lowest keys stay in the current node, the next (middle) key is inserted in the parent, and the rest go to the right sibling.[16] (The newly inserted key might end up in any of the three places.) The situation when the right sibling is full and the left isn't is analogous.[16] When both the sibling nodes are full, then the two nodes (current node and a sibling) are split into three, and one more key is shifted up the tree to the parent node.[16] If the parent is full, then spill/split operation propagates towards the root node.[16] Deleting nodes is somewhat more complex than inserting, however.

- The B*+ tree combines the main B+ tree and B* tree features together.[17]

- B-trees can be turned into order statistic trees to allow rapid searches for the Nth record in key order, or counting the number of records between any two records, and various other related operations.[18]

B-tree usage in databases

[edit]This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (May 2022) |

Sorted file search time

[edit]Sorting and searching algorithms can be characterized by the number of comparison operations that must be performed using order notation. A binary search of a sorted table with N records, for example, can be done in roughly ⌈ log2 N ⌉ comparisons. If the table had 1,000,000 records, then a specific record could be located with at most 20 comparisons: ⌈ log2 (1,000,000) ⌉ = 20.

Large databases have historically been kept on disk drives. The time required to read a record on a disk drive far exceeds the time needed to compare keys once the record is available due to seek time and rotational delay. The seek time may be 0 to 20 or more milliseconds, and the rotational delay averages about half the rotation period. For a 7200 RPM drive, the rotation period is 8.33 milliseconds. For a drive such as the Seagate ST3500320NS, the track-to-track seek time is 0.8 milliseconds and the average reading seek time is 8.5 milliseconds.[19] For simplicity, assume reading from disk takes about 10 milliseconds.

The time required to locate one record out of a million in the example above would be 20 disk reads, each taking 10 milliseconds, which equals 0.2 seconds.

The search time is reduced because individual records are grouped together in a disk block. A disk block might be 16 kilobytes in size. If each record is 160 bytes, then 100 records could be stored in each block. The disk read time above was actually for an entire block. Once the disk head is in position, one or more disk blocks can be read with little delay. With 100 records per block, the last 6 or so comparisons don't need to do any disk reads—the comparisons are all within the last disk block read.

To speed up the search further, the time to do the first 13 to 14 comparisons (which each required disk access) must be reduced.

Index performance

[edit]A B-tree index can be used to improve performance. A B-tree index creates a multi-level tree structure that breaks a database down into fixed-size blocks or pages. Each level of this tree can be used to link those pages via an address location, allowing one page (known as a node, or internal page) to refer to another with leaf pages at the lowest level. One page is typically the starting point of the tree, or the "root". This is where the search for a particular key would begin, traversing a path that terminates in a leaf. Most pages in this structure will be leaf pages which refer to specific table rows.

Because each node (or internal page) can have more than two children, a B-tree index will usually have a shorter height (the distance from the root to the farthest leaf) than a Binary Search Tree. In the example above, initial disk reads narrowed the search range by a factor of two. That can be improved by creating an auxiliary index that contains the first record in each disk block (sometimes called a sparse index). This auxiliary index would be 1% of the size of the original database, but it can be searched quickly. Finding an entry in the auxiliary index would tell us which block to search in the main database; after searching the auxiliary index, we would have to search only that one block of the main database—at a cost of one more disk read.

In the above example, the index would hold 10,000 entries and would take at most 14 comparisons to return a result. Like the main database, the last six or so comparisons in the auxiliary index would be on the same disk block. The index could be searched in about eight disk reads, and the desired record could be accessed in 9 disk reads.

Creating an auxiliary index can be repeated to make an auxiliary index to the auxiliary index. That would create an aux-aux index that would need only 100 entries and would fit in one disk block.

Instead of reading 14 disk blocks to find the desired record, we only need to read 3 blocks. This blocking is the core idea behind the creation of the B-tree, where disk blocks form a hierarchy of levels to make up the index. Reading and searching the first (and only) block of the aux-aux index, which is the root of the tree, identifies the relevant block in aux-index in the level below. Reading and searching that aux-index block identifies the relevant block to read until the final level, known as the leaf level, identifies a record in the main database. Instead of 150 milliseconds, we need only 30 milliseconds to get the record.

The auxiliary indices have turned the search problem from a binary search requiring roughly log2 N disk reads to one requiring only logb N disk reads where b is the blocking factor (the number of entries per block: b = 100 entries per block in our example; log100 1,000,000 = 3 reads).

In practice, if the main database is being frequently searched, the aux-aux index and much of the aux index may reside in a disk cache, so they would not incur a disk read. The B-tree remains the standard index implementation in almost all relational databases, and many nonrelational databases use it as well.[20]

Insertions and deletions

[edit]If the database does not change, then compiling the index is simple to do, and the index need never be changed. If there are changes, managing the database and its index requires additional computation.

Deleting records from a database is relatively easy. The index can stay the same, and the record can just be marked as deleted. The database remains in sorted order. If there are a large number of lazy deletions, then searching and storage become less efficient.[21]

Insertions can be very slow in a sorted sequential file because room for the inserted record must be made. Inserting a record before the first record requires shifting all of the records down one. Such an operation is just too expensive to be practical. One solution is to leave some spaces. Instead of densely packing all the records in a block, the block can have some free space to allow for subsequent insertions. Those spaces would be marked as if they were "deleted" records.

Both insertions and deletions are fast as long as space is available on a block. If an insertion won't fit on the block, then some free space on some nearby block must be found and the auxiliary indices adjusted. The best case is that enough space is available nearby so that the amount of block reorganization can be minimized. Alternatively, some out-of-sequence disk blocks may be used.[20]

Usage in databases

[edit]The B-tree uses all of the ideas described above. In particular, a B-tree:

- keeps keys in sorted order for sequential traversing

- uses a hierarchical index to minimize the number of disk reads

- uses partially full blocks to speed up insertions and deletions

- keeps the index balanced with a recursive algorithm

In addition, a B-tree minimizes waste by making sure the interior nodes are at least half full. A B-tree can handle an arbitrary number of insertions and deletions.[20]

Best case and worst case heights

[edit]Let h ≥ –1 be the height of the classic B-tree (see Tree (data structure) § Terminology for the tree height definition). Let n ≥ 0 be the number of entries in the tree. Let m be the maximum number of children a node can have. Each node can have at most m−1 keys.

It can be shown (by induction for example) that a B-tree of height h with all its nodes completely filled has n = mh+1–1 entries. Hence, the best case height (i.e. the minimum height) of a B-tree is:

Let be the minimum number of children an internal (non-root) node must have. For an ordinary B-tree,

Comer (1979) and Cormen et al. (2001) give the worst case height (the maximum height) of a B-tree as:[22]

Algorithms

[edit]This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Search

[edit]Searching is similar to searching a binary search tree. Starting at the root, the tree is recursively traversed from top to bottom. At each level, the search reduces its field of view to the child pointer (subtree) whose range includes the search value. A subtree's range is defined by the values, or keys, contained in its parent node. These limiting values are also known as separation values.

Binary search is typically (but not necessarily) used within nodes to find the separation values and child tree of interest.

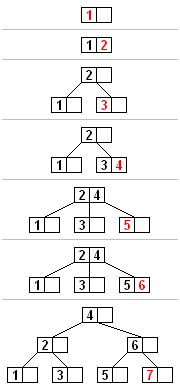

Insertion

[edit]

All insertions start at a leaf node. To insert a new element, search the tree to find the leaf node where the new element should be added. Insert the new element into that node with the following steps:

- If the node contains fewer than the maximum allowed number of elements, then there is room for the new element. Insert the new element in the node, keeping the node's elements ordered.

- Otherwise the node is full, evenly split it into two nodes so:

- A single median is chosen from among the leaf's elements and the new element that is being inserted.

- Values less than the median are put in the new left node, and values greater than the median are put in the new right node, with the median acting as a separation value.

- The separation value is inserted in the node's parent, which may cause it to be split, and so on. If the node has no parent (i.e., the node was the root), create a new root above this node (increasing the height of the tree).

If the splitting goes all the way up to the root, it creates a new root with a single separator value and two children, which is why the lower bound on the size of internal nodes does not apply to the root. The maximum number of elements per node is U−1. When a node is split, one element moves to the parent, but one element is added. So, it must be possible to divide the maximum number U−1 of elements into two legal nodes. If this number is odd, then U=2L and one of the new nodes contains (U−2)/2 = L−1 elements, and hence is a legal node, and the other contains one more element, and hence it is legal too. If U−1 is even, then U=2L−1, so there are 2L−2 elements in the node. Half of this number is L−1, which is the minimum number of elements allowed per node.

An alternative algorithm supports a single pass down the tree from the root to the node where the insertion will take place, splitting any full nodes encountered on the way pre-emptively. This prevents the need to recall the parent nodes into memory, which may be expensive if the nodes are on secondary storage. However, to use this algorithm, we must be able to send one element to the parent and split the remaining U−2 elements into two legal nodes, without adding a new element. This requires U = 2L rather than U = 2L−1, which accounts for why some[which?] textbooks impose this requirement in defining B-trees.

Deletion

[edit]There are two popular strategies for deletion from a B-tree.

- Locate and delete the item, then restructure the tree to retain its invariants, OR

- Do a single pass down the tree, but before entering (visiting) a node, restructure the tree so that once the key to be deleted is encountered, it can be deleted without triggering the need for any further restructuring

The algorithm below uses the former strategy.

There are two special cases to consider when deleting an element:

- The element in an internal node is a separator for its child nodes

- Deleting an element may put its node under the minimum number of elements and children

The procedures for these cases are in order below.

Deletion from a leaf node

[edit]- Search for the value to delete.

- If the value is in a leaf node, simply delete it from the node.

- If underflow happens, rebalance the tree as described in section "Rebalancing after deletion" below.

Deletion from an internal node

[edit]Each element in an internal node acts as a separation value for two subtrees, therefore we need to find a replacement for separation. Note that the largest element in the left subtree is still less than the separator. Likewise, the smallest element in the right subtree is still greater than the separator. Both of those elements are in leaf nodes, and either one can be the new separator for the two subtrees. Algorithmically described below:

- Choose a new separator (either the largest element in the left subtree or the smallest element in the right subtree), remove it from the leaf node it is in, and replace the element to be deleted with the new separator.

- The previous step deleted an element (the new separator) from a leaf node. If that leaf node is now deficient (has fewer than the required number of nodes), then rebalance the tree starting from the leaf node.

Rebalancing after deletion

[edit]Rebalancing starts from a leaf and proceeds toward the root until the tree is balanced. If deleting an element from a node has brought it under the minimum size, then some elements must be redistributed to bring all nodes up to the minimum. Usually, the redistribution involves moving an element from a sibling node that has more than the minimum number of nodes. That redistribution operation is called a rotation. If no sibling can spare an element, then the deficient node must be merged with a sibling. The merge causes the parent to lose a separator element, so the parent may become deficient and need rebalancing. The merging and rebalancing may continue all the way to the root. Since the minimum element count doesn't apply to the root, making the root be the only deficient node is not a problem. The algorithm to rebalance the tree is as follows:

- If the deficient node's right sibling exists and has more than the minimum number of elements, then rotate left

- Copy the separator from the parent to the end of the deficient node (the separator moves down; the deficient node now has the minimum number of elements)

- Replace the separator in the parent with the first element of the right sibling (right sibling loses one node but still has at least the minimum number of elements)

- The tree is now balanced

- Otherwise, if the deficient node's left sibling exists and has more than the minimum number of elements, then rotate right

- Copy the separator from the parent to the start of the deficient node (the separator moves down; deficient node now has the minimum number of elements)

- Replace the separator in the parent with the last element of the left sibling (left sibling loses one node but still has at least the minimum number of elements)

- The tree is now balanced

- Otherwise, if both immediate siblings have only the minimum number of elements, then merge with a sibling sandwiching their separator taken off from their parent

- Copy the separator to the end of the left node (the left node may be the deficient node or it may be the sibling with the minimum number of elements)

- Move all elements from the right node to the left node (the left node now has the maximum number of elements, and the right node – empty)

- Remove the separator from the parent along with its empty right child (the parent loses an element)

- If the parent is the root and now has no elements, then free it and make the merged node the new root (tree becomes shallower)

- Otherwise, if the parent has fewer than the required number of elements, then rebalance the parent[23]

- Note: The rebalancing operations are different for B+ trees (e.g., rotation is different because parent has copy of the key) and B*-tree (e.g., three siblings are merged into two siblings).

Sequential access

[edit]While freshly loaded databases tend to have good sequential behaviour, this behaviour becomes increasingly difficult to maintain as a database grows, resulting in more random I/O and performance challenges.[24]

Initial construction

[edit]A common special case is adding a large amount of pre-sorted data into an initially empty B-tree. While it is quite possible to simply perform a series of successive inserts, inserting sorted data results in a tree composed almost entirely of half-full nodes. Instead, a special "bulk loading" algorithm can be used to produce a more efficient tree with a higher branching factor.

When the input is sorted, all insertions are at the rightmost edge of the tree, and in particular any time a node is split, we are guaranteed that no more insertions will take place in the left half. When bulk loading, we take advantage of this, and instead of splitting overfull nodes evenly, split them as unevenly as possible: leave the left node completely full and create a right node with zero keys and one child (in violation of the usual B-tree rules).

At the end of bulk loading, the tree is composed almost entirely of completely full nodes; only the rightmost node on each level may be less than full. Because those nodes may also be less than half full, to re-establish the normal B-tree rules, combine such nodes with their (guaranteed full) left siblings and divide the keys to produce two nodes at least half full. The only node which lacks a full left sibling is the root, which is permitted to be less than half full.

In filesystems

[edit]In addition to its use in databases, the B-tree (or § Variants) is also used in filesystems to allow quick random access to an arbitrary block in a particular file. The basic problem is turning the file block address into a disk block address.

Some early operating systems, and some highly specialized ones, required the application to allocate the maximum size of a file when the file was created. The file can then be allocated as contiguous disk blocks. In that case, to convert the file block address into a disk block address, the operating system simply adds the file block address to the address of the first disk block constituting the file. The scheme is simple, but the file cannot exceed its created size.

All modern, mainstream operating systems allow a file to grow. The resulting disk blocks may not be contiguous, so mapping logical blocks to physical blocks is more involved.

MS-DOS, for example, used a simple File Allocation Table (FAT). The FAT has an entry for each disk block,[note 1] and that entry identifies whether its block is used by a file and if so, which block (if any) is the next disk block of the same file. So, the allocation of each file is represented as a linked list in the table. In order to find the disk address of file block , the operating system (or disk utility) must sequentially follow the file's linked list in the FAT. Worse, to find a free disk block, it must sequentially scan the FAT. For MS-DOS, that was not a huge penalty because the disks and files were small and the FAT had few entries and relatively short file chains. In the FAT12 filesystem (used on floppy disks and early hard disks), there were no more than 4,080 [note 2] entries, and the FAT would usually be resident in memory. As disks got bigger, the FAT architecture began to confront penalties. On a large disk using FAT, it may be necessary to perform disk reads to learn the disk location of a file block to be read or written.

TOPS-20 (and possibly TENEX) used a 0 to 2 level tree that has similarities to a B-tree.[citation needed] A disk block was 512 36-bit words. If the file fit in a 512 (29) word block, then the file directory would point to that physical disk block. If the file fit in 218 words, then the directory would point to an aux index; the 512 words of that index would either be NULL (the block isn't allocated) or point to the physical address of the block. If the file fit in 227 words, then the directory would point to a block holding an aux-aux index; each entry would either be NULL or point to an aux index. Consequently, the physical disk block for a 227 word file could be located in two disk reads and read on the third.

Apple's filesystem HFS+ and APFS, Microsoft's NTFS,[25] AIX (jfs2) and some Linux filesystems, such as Bcachefs, Btrfs and ext4, use B-trees.

B*-trees are used in the HFS and Reiser4 file systems.

DragonFly BSD's HAMMER file system uses a modified B+-tree.[26]

Performance

[edit]A B-tree grows slower with growing data amount, than the linearity of a linked list. Compared to a skip list, both structures have the same performance, but the B-tree scales better for growing n. A T-tree, for main memory database systems, is similar but more compact.

Variations

[edit]Access concurrency

[edit]Lehman and Yao[27] showed that all the read locks could be avoided (and thus concurrent access greatly improved) by linking the tree blocks at each level together with a "next" pointer. This results in a tree structure where both insertion and search operations descend from the root to the leaf. Write locks are only required as a tree block is modified. This maximizes access concurrency by multiple users, an important consideration for databases and/or other B-tree-based ISAM storage methods. The cost associated with this improvement is that empty pages cannot be removed from the btree during normal operations. (There are strategies to implement node merging.[28][29])

United States Patent 5283894, granted in 1994, appears to show a way to use a 'Meta Access Method'[30] to allow concurrent B+ tree access and modification without locks. The technique accesses the tree 'upwards' for both searches and updates by means of additional in-memory indexes that point at the blocks in each level in the block cache. No reorganization for deletes is needed and there are no 'next' pointers in each block as in Lehman and Yao.

Parallel algorithms

[edit]Since B-trees are similar in structure to red-black trees, parallel algorithms for red-black trees can be applied to B-trees as well.

Maple tree

[edit]A Maple tree is a B-tree developed for use in the Linux kernel to reduce lock contention in virtual memory management.[31][32][33]

(a,b)-tree

[edit](a,b)-trees are generalizations of B-trees. B-trees require that each internal node have a minimum of children and a maximum of children, for some preset value of . In contrast, an (a,b)-tree allows the minimum number of children for an internal node to be set arbitrarily low. In an (a,b)-tree, each internal node has between a and b children, for some preset values of a and b.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For FAT, what is called a "disk block" here is what the FAT documentation calls a "cluster", which is a fixed-size group of one or more contiguous whole physical disk sectors. For the purposes of this discussion, a cluster has no significant difference from a physical sector.

- ^ Two of these were reserved for special purposes, so only 4078 could actually represent disk blocks (clusters).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bayer, R.; McCreight, E. (July 1970). "Organization and maintenance of large ordered indices" (PDF). Proceedings of the 1970 ACM SIGFIDET (Now SIGMOD) Workshop on Data Description, Access and Control - SIGFIDET '70. Boeing Scientific Research Laboratories. p. 107. doi:10.1145/1734663.1734671. S2CID 26930249.

- ^ a b c d Comer 1979.

- ^ "BTreeMap in std::collections - Rust". doc.rust-lang.org.

- ^ "abseil / Abseil Containers". abseil.io.

- ^ a b c Bayer & McCreight 1972.

- ^ Comer 1979, p. 123 footnote 1.

- ^ a b Weiner, Peter G. (30 August 2013). "4- Edward M McCreight" – via Vimeo.

- ^ "Stanford Center for Professional Development". scpd.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-06-04. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ^ a b Knuth 1998, p. 483.

- ^ Folk & Zoellick 1992, p. 362.

- ^ a b Folk & Zoellick 1992, p. 363.

- ^ Bayer & McCreight (1972) avoided the issue by saying an index element is a (physically adjacent) pair of (x, a) where x is the key, and a is some associated information. The associated information might be a pointer to a record or records in a random access, but what it was didn't really matter. Bayer & McCreight (1972) states, "For this paper the associated information is of no further interest."

- ^ Folk & Zoellick 1992, p. 379.

- ^ Knuth 1998, p. 488.

- ^ a b c d e f Tomašević, Milo (2008). Algorithms and Data Structures. Belgrade, Serbia: Akademska misao. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-86-7466-328-8.

- ^ Rigin A. M., Shershakov S. A. (2019-09-10). "SQLite RDBMS Extension for Data Indexing Using B-tree Modifications". Proceedings of the Institute for System Programming of the RAS. 31 (3). Institute for System Programming of the RAS (ISP RAS): 203–216. doi:10.15514/ispras-2019-31(3)-16. S2CID 203144646. Retrieved 2021-08-29.

- ^ "Counted B-Trees". www.chiark.greenend.org.uk. Retrieved 2024-12-27.

- ^ Product Manual: Barracuda ES.2 Serial ATA, Rev. F., publication 100468393 (PDF). Seagate Technology LLC. 2008. p. 6.

- ^ a b c Kleppmann, Martin (2017). Designing Data-Intensive Applications. Sebastopol, California: O'Reilly Media. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-449-37332-0.

- ^ Jan Jannink. "Implementing Deletion in B+-Trees". Section "4 Lazy Deletion".

- ^ Comer 1979, p. 127; Cormen et al. 2001, pp. 439–440

- ^ "Deletion in a B-tree" (PDF). cs.rhodes.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "Cache Oblivious B-trees". State University of New York (SUNY) at Stony Brook. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ^ Mark Russinovich (30 June 2006). "Inside Win2K NTFS, Part 1". Microsoft Developer Network. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ Matthew Dillon (2008-06-21). "The HAMMER Filesystem" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Lehman, Philip L.; Yao, s. Bing (1981). "Efficient locking for concurrent operations on B-trees". ACM Transactions on Database Systems. 6 (4): 650–670. doi:10.1145/319628.319663. S2CID 10756181.

- ^ Wang, Paul (1 February 1991). "An In-Depth Analysis of Concurrent B-tree Algorithms" (PDF). dtic.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ "Downloads - high-concurrency-btree - High Concurrency B-Tree code in C - GitHub Project Hosting". GitHub. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- ^ "Lockless concurrent B-tree index meta access method for cached nodes".

- ^ "Introducing maple trees [LWN.net]". lwn.net.

- ^ "Maple Tree — The Linux Kernel documentation". docs.kernel.org.

- ^ "Introducing the Maple Tree [LWN.net]". lwn.net.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Paul E. Black. "(a,b)-tree". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. NIST.

This article incorporates public domain material from Paul E. Black. "(a,b)-tree". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. NIST.

Sources

[edit]- Bayer, R.; McCreight, E. (1972). "Organization and Maintenance of Large Ordered Indexes" (PDF). Acta Informatica. 1 (3): 173–189. doi:10.1007/bf00288683. S2CID 29859053..

- Comer, Douglas (June 1979). "The Ubiquitous B-Tree". Computing Surveys. 11 (2): 123–137. doi:10.1145/356770.356776. ISSN 0360-0300. S2CID 101673..

- Cormen, Thomas; Leiserson, Charles; Rivest, Ronald; Stein, Clifford (2001). Introduction to Algorithms (Second ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. pp. 434–454. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Chapter 18: B-Trees.

- Folk, Michael J.; Zoellick, Bill (1992). File Structures (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-55713-4..

- Knuth, Donald (1998). Sorting and Searching. The Art of Computer Programming. Vol. 3 (Second ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-89685-0. Section 6.2.4: Multiway Trees, pp. 481–491. Also, pp. 476–477 of section 6.2.3 (Balanced Trees) discusses 2–3 trees.

Original papers

[edit]- Bayer, Rudolf; McCreight, E. (July 1970), Organization and Maintenance of Large Ordered Indices, vol. Mathematical and Information Sciences Report No. 20, Boeing Scientific Research Laboratories.

- Bayer, Rudolf (1971). "Binary B-Trees for Virtual Memory". Proceedings of 1971 ACM-SIGFIDET Workshop on Data Description, Access and Control. San Diego, California..

External links

[edit]- B-tree lecture by David Scot Taylor, SJSU

- B-Tree visualisation (click "init")

- Animated B-Tree visualization

- B-tree and UB-tree on Scholarpedia Curator: Dr Rudolf Bayer

- B-Trees: Balanced Tree Data Structures Archived 2010-03-05 at the Wayback Machine

- NIST's Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures: B-tree

- B-Tree Tutorial

- The InfinityDB BTree implementation

- Cache Oblivious B(+)-trees

- Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures entry for B*-tree

- Open Data Structures - Section 14.2 - B-Trees, Pat Morin

- Counted B-Trees

- B-Tree .Net, a modern, virtualized RAM & Disk implementation Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

Bulk loading

- Shetty, Soumya B. (2010). A user configurable implementation of B-trees (Thesis). Iowa State University.

- Kaldırım, Semih (28 April 2015). "File Organization, ISAM, B+ Tree and Bulk Loading" (PDF). Ankara, Turkey: Bilkent University. pp. 4–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- "ECS 165B: Database System Implementation: Lecture 6" (PDF). University of California, Davis. 9 April 2010. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- "BULK INSERT (Transact-SQL) in SQL Server 2017". Microsoft Docs. 6 September 2018.

B-tree

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Development

The B-tree was invented in 1970 by Rudolf Bayer and Edward M. McCreight while they were researchers at Boeing Scientific Research Laboratories.[2] Their work aimed to develop an advanced indexing structure for managing large volumes of ordered data in database systems. The structure was first presented in the paper "Organization and Maintenance of Large Ordered Indexes" at the ACM SIGFIDET Workshop on Data Description, Access and Control, held in Houston, Texas, on November 15, 1970.[2] In this early formulation, the B-tree was described as a self-balancing multiway search tree designed to optimize performance in environments with slow secondary storage. The primary motivation for creating the B-tree stemmed from the inefficiencies of traditional binary search trees when applied to large datasets stored on disk-based systems. Binary search trees, while efficient in main memory, often resulted in deep trees with heights proportional to the logarithm base 2 of the dataset size, leading to numerous costly I/O operations since each level might require accessing a separate disk block.[2] Bayer and McCreight sought a solution that minimized disk accesses by allowing nodes to hold multiple keys—typically tuned to the block size of the storage device—thus maintaining a low tree height (logarithmic in base roughly equal to the node fanout) and ensuring balanced growth. This approach achieved retrieval, insertion, and deletion times proportional to the logarithm of the index size, with storage utilization of at least 50%.[2] Experimental results in their 1970 paper demonstrated practical viability, such as maintaining an index of 100,000 keys at a rate of at least 4 transactions per second on an IBM 360/44 system with 2311 disks.[2] The B-tree was initially conceptualized as a height-balanced m-way search tree. A formal version of the paper was published in 1972 in Acta Informatica, solidifying the B-tree's definition and analysis, including bounds on performance and optimal parameter selection for device characteristics.[1] This publication marked a key milestone in the structure's adoption for database indexing.Key Publications and Influences

The seminal introduction of the B-tree occurred in the 1972 paper "Organization and Maintenance of Large Ordered Indexes" by Rudolf Bayer and Edward M. McCreight, published in Acta Informatica. This work presented the core concepts of the B-tree as a balanced multiway search tree designed for efficient indexing of large datasets on disk-based storage, emphasizing balanced height and minimized disk accesses through variable fanout nodes.[1] In 1973, Donald E. Knuth provided a rigorous mathematical analysis of B-trees in The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 3: Sorting and Searching, formalizing their properties, insertion and deletion algorithms, and generalizations to multiway trees. Knuth's treatment included proofs of balance invariants and performance bounds, establishing B-trees as a foundational structure in sorting and searching literature. Douglas Comer's 1979 survey "The Ubiquitous B-Tree," published in ACM Computing Surveys, synthesized the growing body of research on B-trees and their variants, underscoring their rapid adoption as the standard for database indexing by the late 1970s. The paper reviewed implementations in systems like System R and highlighted B-trees' efficiency for sequential and random access in secondary storage.[3] Bayer's subsequent work in the 1970s influenced variants like the prefix B-tree, introduced in the 1977 paper "Prefix B-Trees" co-authored with Karl Unterauer in ACM Transactions on Database Systems, which incorporated key compression to enhance storage efficiency while preserving B-tree balance. This contributed to the evolution of B+ trees, where data resides solely in leaf nodes linked for sequential access. B-trees and their variants were integrated as the primary indexing mechanism in relational database systems adhering to SQL standards, such as IBM's DB2 and Oracle, enabling efficient query processing in commercial DBMS by the 1980s.[4]Definition and Properties

Formal Definition

A B-tree of order is a self-balancing search tree in which each node has at most children, corresponding to at most keys stored in sorted order within the node.[1] The structure satisfies the search tree invariant: within any node, the keys are in increasing order, all keys in the subtrees to the left of a key are less than that key, and all keys in the subtrees to the right are greater than that key.[1] Key properties ensure balance and efficiency. All leaves reside at the same level, maintaining a uniform height across the tree.[1] For internal nodes other than the root, the number of keys ranges between and , while the root may contain fewer keys but at least one unless it is a leaf.[1] The root has at least two children unless it is a leaf node itself.[1] No violations of these balance and ordering properties are permitted in a valid B-tree.[1] In a common notational variant, let ; then, for non-root nodes, the number of keys satisfies .[1] This formulation highlights the bounded branching factor that guarantees logarithmic height relative to the number of keys , with height at most .[1]Terminology Variations

The terminology surrounding B-trees exhibits variations across foundational literature and implementations, primarily in how parameters defining node capacity are denoted and interpreted. In Knuth's seminal treatment, the order of a B-tree is specified as , representing the maximum number of children per node, with non-root nodes required to have at least children to maintain balance.[5] In contrast, Cormen et al. employ the minimum degree (where ), stipulating that non-root nodes hold between and keys, which corresponds to to children; this parameterization emphasizes the lower bound on node occupancy for efficient disk access. Distinctions between the B-tree and its B+-tree variant also contribute to terminological ambiguity, particularly in early works. The original B-tree formulation by Bayer and McCreight permits keys and associated data records to reside in both internal and leaf nodes, enabling direct access at any level during searches.[1] However, some early publications conflated these with B+-trees, a refinement where data records are confined to leaf nodes linked sequentially for efficient range queries, while internal nodes contain only navigational keys—enhancing sequential access at the cost of slightly deeper trees.[6] Further variations arise in descriptions of node fullness and balance enforcement. Standard B-trees require nodes to be at least half full (minimum keys, where is the order parameter), but "full" nodes are typically those at maximum capacity; some treatments demand exactly children for full internal nodes, whereas others incorporate flexible underflow handling during deletions, such as borrowing or merging siblings to avoid immediate reorganization.[6] Related variants like B*-trees enforce higher occupancy (at least two-thirds full) through redistribution rather than splitting, altering the threshold for "proper" balance.[6] In database contexts, particularly SQL implementations, "B-tree index" often denotes a B+-tree variant without explicit distinction, as seen in systems like SQL Server where rowstore indexes use B+-tree structures with data solely in leaves to optimize I/O for large-scale queries.[7] This convention prioritizes the variant's sequential access benefits, masking the underlying difference from the classical B-tree.[6]Structure

Node Composition

A B-tree node consists of a sorted array of keys and an array of child pointers, where a node with keys holds up to child pointers that direct to subtrees containing values less than, between, or greater than the keys.[8] The keys within each node are maintained in monotonically increasing order, facilitating efficient range-based navigation.[8] Leaf nodes, which store the actual data entries or pointers to them, contain no child pointers.[8] In terms of storage, the keys and child pointers are typically organized in contiguous arrays, with child pointers interleaving the keys such that the -th key separates the ranges of the -th and -th child subtrees.[8] Implementations often include additional metadata, such as a flag indicating whether the node is internal or a leaf, and a pointer to the parent node to support upward traversal during operations. This structure allows for compact representation and straightforward access patterns in memory or on secondary storage. The capacity of a node in a B-tree is defined using the minimum degree : non-root nodes must hold at least keys, while the maximum is keys.[8] The root node may hold as few as 1 key but follows the same upper limit. Overflow occurs when insertion would exceed keys, triggering a split to redistribute content and maintain these invariants.[8] For example, in a B-tree with minimum degree (corresponding to traditional order ), a non-root internal node holds between 2 and 5 keys (3 to 6 children), arranged as: child pointer 0, key 1, child pointer 1, key 2, child pointer 2, key 3, child pointer 3, key 4, child pointer 4, key 5, child pointer 5 (for a full node). This interleaving ensures that all keys in the subtree rooted at child (for ) satisfy the appropriate range relative to the node's keys. Leaf nodes in this case would hold 2 to 5 keys with no children. B-trees are designed with disk-oriented storage in mind, where each node corresponds to a fixed-size page aligned with disk block sizes, such as 4 KB, to minimize input/output operations by loading entire nodes in single transfers.[8] The minimum degree is chosen such that nodes fit these blocks while accommodating key and pointer sizes, often resulting in values around 100 to 500 for typical hardware.[8]Tree Properties and Invariants

A B-tree maintains two fundamental invariants that ensure its efficiency as a search structure: the balance invariant and the ordering invariant. The balance invariant requires that all leaf nodes reside at the same depth from the root, guaranteeing a uniform height across the tree. This property, as defined in the original formulation, ensures that "all leaves appear on the same level," preventing uneven growth that could degrade search performance. The ordering invariant stipulates that an in-order traversal of the tree yields the keys in sorted order, with each node's keys partitioning the key spaces of its subtrees such that all keys in a left subtree are less than the node's smallest key, and all keys in a right subtree are greater than its largest key. Specifically, "the keys in a node partition the keys in its subtrees," maintaining a consistent binary search property generalized to multi-way branching. To preserve balance and efficiency, B-trees enforce strict occupancy rules on node fullness, preventing underflow and overflow conditions from persisting. Non-root nodes must contain at least keys and at most keys, where is the minimum degree (minimum number of children for non-root internal nodes); leaves follow analogous bounds on key counts (with no children). These thresholds ensure nodes remain sufficiently populated, avoiding sparse structures that could lead to excessive height. The root node is exempt from the minimum occupancy rule and may hold as few as one key (and two children), allowing flexibility at the top level without compromising overall balance. These invariants collectively prevent the B-tree from degenerating into a linear or skewed structure, such as a linked list, which would result in linear-time operations. The balance invariant, combined with the minimum occupancy, bounds the tree height at , where is the number of keys: the minimum number of keys grows exponentially with height due to the fan-out factor (at least children per non-root internal node), ensuring the depth cannot exceed logarithmic proportions. Thus, "the height of the tree remains ," safeguarding logarithmic access times.Operations

Searching

The search operation in a B-tree begins at the root node, where the target key is compared against the sorted keys stored in the node to determine the appropriate child subtree for further traversal. The keys in each node are maintained in non-decreasing order, allowing the algorithm to identify the correct branch by finding the smallest index such that the target key satisfies the -th key (or falls before the first key if smaller than all). The process then recurses on the corresponding child pointer, descending level by level until a leaf node is reached. Upon reaching a leaf node, the algorithm scans the keys to check for an exact match with the target key . If a match is found, the search returns the position of the key (or associated data pointer); otherwise, it concludes that the key is not present in the tree. In the original B-tree design, keys and data may reside in internal nodes as well, permitting the search to potentially succeed before descending to a leaf if the key is encountered en route. However, the traversal always follows the invariant that all leaves are at the same depth, ensuring balanced descent.[9] The search can be implemented efficiently using binary search within each node to locate the branching index, rather than a linear scan, especially for nodes with high degree. The following pseudocode outlines the recursive search procedure, adapted from standard descriptions and assuming data is stored only in leaves for simplicity (with linear scan for illustration; binary search replaces the while loop in practice):B-TREE-SEARCH(x, k)

1 i ← 1

2 while i ≤ n[x] and k > key[x][i]

3 i ← i + 1

4 if i ≤ n[x] and k = key[x][i]

5 if leaf[x]

6 return ASSOCIATED-DATA[x][i] // or position i

7 else

8 return B-TREE-SEARCH(c[x][i], k) // recurse on child, may find in internal

9 else if leaf[x]

10 return NIL // not found

11 else

12 return B-TREE-SEARCH(c[x][i], k) // recurse on next child

B-TREE-SEARCH(x, k)

1 i ← 1

2 while i ≤ n[x] and k > key[x][i]

3 i ← i + 1

4 if i ≤ n[x] and k = key[x][i]

5 if leaf[x]

6 return ASSOCIATED-DATA[x][i] // or position i

7 else

8 return B-TREE-SEARCH(c[x][i], k) // recurse on child, may find in internal

9 else if leaf[x]

10 return NIL // not found

11 else

12 return B-TREE-SEARCH(c[x][i], k) // recurse on next child

Insertion

Insertion into a B-tree begins by searching for the appropriate leaf node where the new key belongs, following the same path as a search operation would take, which involves descending from the root through internal nodes to a leaf based on key comparisons.[9] Implementations may use top-down (splitting full nodes on descent) or bottom-up (insert then split if needed) approaches; the description and pseudocode here follow the top-down for consistency. Once the appropriate leaf is identified, the new key is inserted into the node in its correct sorted position among the existing keys.[9] If the node has fewer than its maximum capacity of keys—where is the minimum degree of the tree—the insertion completes without further action, maintaining the tree's balance properties.[9] Should a full node be encountered during descent, it is split before recursing to ensure space for the insertion and to maintain invariants. The splitting process for a full node with keys redistributes them such that the left node retains the first keys, the right node receives the last keys (positions to ), and the median key (at position ) is promoted to the parent node.[9] This promotion inserts the median key into the parent in the appropriate position, effectively creating two sibling nodes from the original one, with the parent now pointing to both; child pointers are also split, with the first children to the left and the last to the right.[9] The split ensures both new nodes are at least half full, preserving the B-tree's minimum occupancy guarantee except possibly at the root. After splitting, the insertion proceeds into the appropriate child. If the parent node becomes full after inserting the median key and thus overflows, the splitting process recurses upward, applying the same redistribution to the parent and promoting its median to its own parent, continuing until a non-full node is encountered or the root is reached.[9] In the case of root overflow, a new root is created containing only the median key from the split, with the original root becoming its left child and the new right node from the split becoming its right child; this operation increases the height of the tree by one level.[9] Height increases occur when the root splits and happen after a number of insertions that grows exponentially with the current height, ensuring the overall height remains logarithmic.[9] The insertion algorithm is typically implemented recursively to handle these cases efficiently. A high-level procedure, such asB-TREE-INSERT(T, k), first checks if the root is full; if so, it allocates a new root, splits the old root as a child, and sets the new root to point to the split children with the median in between.[9] It then calls a subroutine like B-TREE-INSERT-NONFULL(x, k) on the root (or the appropriate node), which assumes the current node is not full.[9] In B-TREE-INSERT-NONFULL, the algorithm finds the child interval for , and if descending to an internal node's child that is full, it preemptively calls SPLIT-CHILD(x, i) to split that child before recursing.[9] The SPLIT-CHILD(x, i) procedure allocates a new node , moves the last keys (y.key[t+1] to y.key[2t-1]) and the last child pointers (y.c[t+1] to y.c[2t]) from the full child to , adjusts 's key count to , inserts (the median) into at position , and sets .[9]

For illustration, consider a B-tree of minimum degree (maximum 3 keys per node) with a leaf containing keys [10, 20, 30] that is full. Before inserting 25, split it: left [10], median 20 promoted to parent, right [11]. Then insert 25 into the right node, yielding [25, 30]. If the parent was [12] and becomes [15, 20] after promotion, no further split occurs; otherwise, propagation continues as needed.[9] This top-down splitting approach avoids recursion on the way back up and aligns with the standard maintenance strategy for ordered indexes.

Deletion

Deletion in a B-tree involves locating the key to remove and ensuring the tree maintains its balance properties after the operation. The process begins by searching for the key, similar to the search operation, until reaching the node containing it. If the key is found in a leaf node, it is simply removed from that node. If the key resides in an internal node, it is replaced by its inorder successor (the smallest key in the right subtree) or predecessor (the largest key in the left subtree), and then the successor or predecessor is deleted from its leaf node in the corresponding subtree. This replacement ensures that the deletion ultimately occurs at a leaf, preserving the tree's search structure. After removing the key from a leaf, the node must be checked for underflow, which occurs if the node has fewer than the minimum number of keys, denoted as where is the minimum degree of the tree (each non-root node must have at least children). If no underflow happens, the deletion is complete. In case of underflow, the algorithm attempts to restore the minimum by borrowing a key from an adjacent sibling node, if possible. To borrow, the parent node redistributes a key and a child pointer with the underfull node and its sibling, provided the sibling has more than the minimum keys. If borrowing is not feasible (i.e., both siblings are at or below the minimum), the underfull node is merged with one sibling, incorporating the separating key from the parent into the new combined node, which now has at most keys. This merge reduces the number of children in the parent by one, potentially causing an underflow that propagates upward toward the root. The underflow resolution recurses up the tree levels until no further underflow occurs or the root is reached. At the root, special handling applies: if the root has only one key before deletion and an underflow leads to its merger with a child, the root is removed, and its child becomes the new root, decreasing the tree's height by one. This height reduction is the only circumstance in which B-tree deletion can decrease the overall height, contrasting with insertion which may increase it. The entire deletion maintains the B-tree invariants, ensuring all leaves remain at the same level and nodes satisfy the key and child count constraints. The following pseudocode outlines the core deletion procedure for a node, assuming the key has been located and the tree uses minimum degree :B-TREE-DELETE(node, key, t)

if node is a leaf

remove key from node

else

if key < node.keys[1]

i = 1

else

i = find position of key in node

successor = DISK-READ(pointer to min key in node.children[i+1])

copy successor to node's key position

B-TREE-DELETE(node.children[i+1], successor, t) // recursive delete in subtree

if node has fewer than t-1 keys // underflow

handle underflow by borrow or merge with sibling via parent

if node is root and has 0 keys

make node's sole child the new root // height decreases

B-TREE-DELETE(node, key, t)

if node is a leaf

remove key from node

else

if key < node.keys[1]

i = 1

else

i = find position of key in node

successor = DISK-READ(pointer to min key in node.children[i+1])

copy successor to node's key position

B-TREE-DELETE(node.children[i+1], successor, t) // recursive delete in subtree

if node has fewer than t-1 keys // underflow

handle underflow by borrow or merge with sibling via parent

if node is root and has 0 keys

make node's sole child the new root // height decreases

Analysis

Height Bounds

The height of a B-tree, defined as the number of edges from the root to a leaf, is bounded both above and below for a given number of keys , ensuring balanced performance regardless of insertion order. These bounds arise from the tree's structural invariants: non-root nodes have between and keys, where and is the order (maximum children per node), leading to minimum and maximum children per non-root node.[13] In the worst case, the height is maximized when nodes are as sparse as possible while respecting the minimum occupancy. Here, the root has at least 2 children, and each subsequent level has the minimum children per node. The minimum number of nodes at level (for ) is thus . Accounting for the minimum keys per non-root node and 1 key in the root, the total number of keys satisfiesSolving for , the worst-case height is

or more precisely,

This bound holds because the root contributes 1 key and at least 2 subtrees, each subtree having at least keys and children, propagating minimally down to height .[13] In the best case, the height is minimized when nodes are fully packed with the maximum keys (or children). This yields a lower bound on height of

for large , as the tree approximates a complete -ary tree in terms of key capacity per level.[13] These height bounds guarantee that all search, insertion, and deletion operations take time in the worst case, as each operation traverses at most levels, independent of the specific key distribution. This logarithmic scaling is fundamental to B-trees' efficiency in disk-based storage systems.[13]

Time Complexity

The time complexity of search, insertion, and deletion operations in a B-tree is in the comparison model, where is the number of keys and is the minimum degree (branching factor).[1] This bound arises because each operation traverses at most the height of the tree, performing a constant amount of work per level, and the height is bounded by .[14] In the disk access model, where each node corresponds to a fixed-size block and accessing a node requires a disk I/O operation, the I/O complexity for these operations is , as the traversal may involve reading or writing one block per level.[15] The total cost per operation can be approximated as , where is the height and is the time for a single block read or write.[16] The space complexity of a B-tree storing keys is , with the high fanout (often tuned to the disk block size) reducing the constant factors by packing multiple keys and pointers per node.[1] Insertions and deletions maintain this efficiency, with occasional node splits or merges incurring amortized cost due to the infrequency of height changes across a sequence of operations.[12] Compared to balanced binary search trees like AVL or red-black trees, B-trees exhibit superior performance in disk-based systems because their larger fanout results in fewer levels (typically 3–4 for millions of keys), minimizing expensive I/O operations, though they require more space per node to achieve this.[14]Applications

Database Indexing

B-trees play a central role in database indexing by providing efficient access to large datasets stored on disk, minimizing the number of I/O operations required for queries. In relational database management systems (RDBMS), B-trees are commonly employed to create secondary indexes on table columns, allowing rapid lookups without scanning entire tables. For instance, PostgreSQL uses B-tree indexes as the default type for secondary indexes on sortable data types, storing index entries separately from the main table data to support efficient retrieval. Similarly, MySQL's InnoDB storage engine implements B-trees (specifically B+ trees) for secondary indexes, where each index entry includes the indexed column values along with the primary key to reference the clustered table data. These structures ensure balanced tree heights, typically logarithmic in the number of keys, which is crucial for maintaining performance as databases scale to millions or billions of rows. B-tree indexes excel in supporting both equality searches and range queries through traversal to the leaf level, where relevant data pointers are stored in sorted order. Equality searches use the index's operator class to compare keys directly, enabling O(log n) time complexity for point lookups. Range queries, such as those using operators like<, >, <=, or >=, traverse the tree to the appropriate leaf and then scan sequentially along linked leaves, avoiding full table scans for conditions like "WHERE age BETWEEN 20 AND 30". This leaf-level traversal leverages the sorted nature of the keys, making B-trees particularly suitable for SQL queries involving sorting or filtering on indexed columns.

A prevalent variant in database systems is the B+ tree, where all data records or pointers reside exclusively in the leaf nodes, while internal nodes contain only routing keys to guide searches downward. This design separates indexing from data storage, allowing internal nodes to maximize fanout and reduce tree height, while leaf nodes support efficient sequential access via bidirectional pointers between siblings. Such organization enhances range query performance by enabling linear scans at the leaves without backtracking through internal levels.

For initializing indexes on large datasets, databases often employ bulk loading techniques to construct B-trees more efficiently than incremental insertions. The process begins by sorting the data on the index key, then filling leaf pages to a specified fill factor (e.g., 75%) from the bottom up, followed by building internal nodes level by level. This bottom-up approach minimizes page splits and ensures higher initial utilization, reducing I/O overhead during index creation.

To handle concurrent operations in multi-user environments, B-tree implementations incorporate node-level locking protocols that maintain tree invariants while supporting multi-version concurrency control (MVCC). In systems like Oracle, short-term latches protect individual nodes during traversal and modification, combined with row-level locking to prevent conflicts, allowing readers to access consistent snapshots without blocking writers. These mechanisms ensure high throughput under concurrent read-write workloads by isolating operations at the granularity of tree pages.

Filesystem Implementation

B-trees are widely employed in modern filesystems to manage directory structures, where they organize file entries for efficient lookups and maintenance. In systems such as NTFS and XFS, directories are represented as B+ trees, with keys consisting of filenames and values pointing to inode-like structures containing file metadata and location information.[18][19] This structure enables logarithmic-time operations for searching, inserting, and deleting directory entries, allowing these filesystems to handle directories with millions of files without performance degradation from linear scans.[19] Beyond directories, B-trees address file allocation challenges, particularly extents and fragmentation, by tracking free space maps. For instance, Btrfs utilizes a dedicated free space tree—a B-tree implementation—to monitor available blocks, improving allocation efficiency and reducing fragmentation in copy-on-write environments.[20] This approach supports dynamic extent management, where fragmented files can be mapped via tree nodes rather than fixed arrays, enhancing overall storage utilization. A notable example is Apple's APFS (Apple File System) in macOS, which employs B-trees in its file system tree to map hierarchical paths to file and folder metadata. The file system B-tree uses composite keys of parent identifiers and filenames to store records with details like permissions, timestamps, and extent references, facilitating rapid traversal of the volume hierarchy.[21] Compared to linear directory formats, B-trees offer superior scalability for both HDDs and SSDs by minimizing disk seeks through balanced node sizes aligned with block boundaries, while filesystem caches can prioritize hot nodes—frequently accessed tree levels—for faster in-memory operations.[22] This design ensures consistent performance as file counts grow, making B-trees essential for large-scale storage environments.Variants

B+ Trees

A B+ tree is a variant of the B-tree data structure designed primarily to optimize range queries and sequential access in disk-based storage systems. Unlike traditional B-trees, where data records may be stored in internal nodes, B+ trees store all data values exclusively in the leaf nodes, while internal nodes contain only keys used for routing searches to the appropriate child. This separation allows internal nodes to be more compact, as they do not need space for data payloads, and enables the leaves to be connected via pointers to form a doubly or singly linked list in sorted order.[6] The properties of B+ trees closely mirror those of B-trees in terms of balance and branching factor. Each internal node can have between and children, where is the order of the tree, ensuring that all leaves are at the same depth and maintaining a minimum occupancy of roughly 50% to guarantee logarithmic height. Leaf nodes store between and keys (and associated data), with the keys in each leaf sorted and the leaves themselves linked sequentially to support traversal. The separator keys in internal nodes are typically copies of the smallest key in the corresponding subtree's leaves, facilitating efficient search without duplicating data.[6] Insertion in a B+ tree follows a process similar to that in B-trees but adapted for leaf-only data storage. To insert a key-value pair, the search path to the appropriate leaf is traversed, and if the leaf is not full, the pair is added and the list links updated if necessary. If the leaf overflows, it is split into two nodes of roughly equal size, and a copy of the first key from the right sibling leaf is promoted to the parent as a routing separator—without promoting any data value. This split may propagate upward if the parent fills, potentially creating a new root and increasing the height. The operation maintains the sorted order and balance, with an amortized cost of disk accesses.[6] Deletion in a B+ tree also occurs only at the leaves. The target key-value pair is located and removed from its leaf; if the leaf remains above the minimum occupancy, the operation concludes after possibly updating the parent separator to the new smallest key in that subtree. If underflow occurs, the algorithm attempts to borrow a key from an adjacent leaf (rotating via the sibling and updating separators), or merges the underfull leaf with a sibling, propagating the underflow upward if needed. Merges may reduce the height if the root becomes a single child. Like insertion, deletion ensures balance and runs in time. Detailed algorithms for these operations, including handling of separator keys, are outlined in foundational analyses of index structures.[23] The primary advantages of B+ trees stem from their leaf-linked structure, which enables efficient sequential scans and range queries by allowing traversal of the linked leaves without revisiting internal nodes—requiring at most one additional access per "next" operation compared to the full for random jumps in standard B-trees. This design also improves cache locality in memory hierarchies, as consecutive keys are physically adjacent in the leaf chain, reducing I/O for disk-based applications. For example, processing the next key after a find requires traversing the leaf links rather than restarting from the root, cutting average access costs significantly for ordered data access patterns.[6] The height bounds of a B+ tree are analogous to those of a B-tree, ensuring performance for search, insertion, and deletion, but with the key distinction that all data keys reside solely in the leaf level. Specifically, the maximum height satisfies , derived from the maximum branching factor in internal nodes and maximum keys per leaf , while the minimum height follows from the minimum branching . This formulation highlights how the leaf level bears the full load of keys, making B+ trees particularly space-efficient for large datasets where internal nodes serve purely as an index.[6]Other Extensions