Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Slipping

View on WikipediaSlipping is a technique used in boxing that is similar to bobbing. It is considered one of the four basic defensive strategies, along with blocking, holding, and clinching. It is performed by moving the head to either side so that the opponent's punches "slip" by the boxer.[1]

Slipping punches allows the fighter to recover quicker and counter punches faster than the opponent can reset into proper fighting stance. In boxing, timing is known to be a key factor in the outcome. Timing your slips correctly is essential in protecting yourself and saving energy. Slipping, if done incorrectly, can be dangerous as it exposes you to a counter-punch and an unbalanced stance.

-

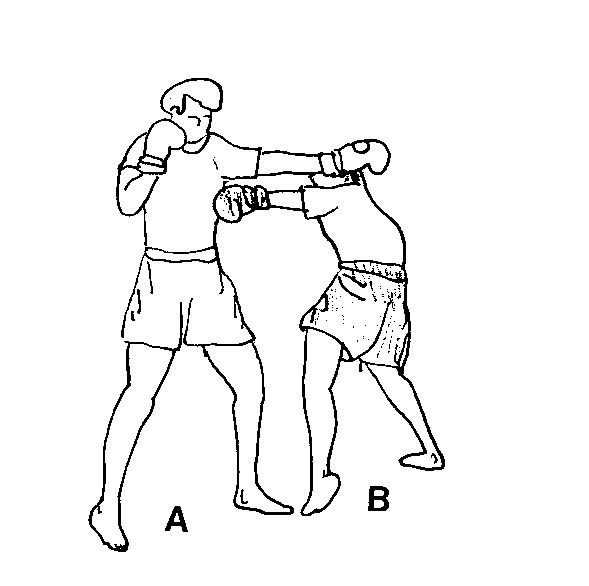

Slipping outside

-

Slipping inside

How to slip punches

[edit]There are multiple ways to slip punches in boxing, but the most basic types are slipping the inside jab, and outside jab. When slipping an outside jab, your body weight needs to be centered. As your opponent throws the jab, rotate your body clockwise and lean slightly to your right, which shifts weight to your rear leg. Pivot both your feet in the same direction. This places you on the outside of your opponent's jab, giving you the ability to counter punch over their jab. For the inside jab, as the opponent throws the jab, rotate your body counter-clockwise, lean slightly to your left and put weight on your lead leg. It's possible to just lean without rotating, but rotating helps the movement of your guard. Raise your rear hand ready for the opponent to throw a left hook.

Common mistakes

[edit]There are many different mistakes you can make when trying to slip a punch:

- Slipping too early

- Slipping too wide

- Slipping inside the cross

- Only moving your head

- Dropping your guard

How to master slipping

[edit]The best method to mastering slipping is practice against an opponent, preferably someone that is taller than you and has a longer reach. Another method is a slip bag you can hang up and move back and forth. This helps you improve movement, timing, and eye coordination while performing a slip. Repetition and patience is key to mastering slipping.

References

[edit]- ^ Allanson-Winn, R. G. (1911). "Chapter 4: Guarding & 'Slipping'". Boxing. Bat Mullins (preface). London: G. Bell & Sons. p. 22. OCLC 1080858348. Retrieved 19 June 2021.