Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

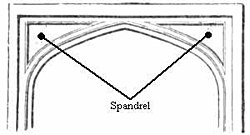

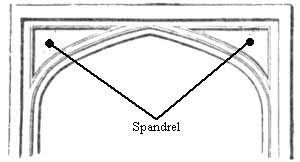

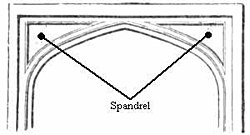

Spandrel

View on Wikipedia

A spandrel[1] is a roughly triangular space, usually found in pairs, between the top of an arch and a rectangular frame, between the tops of two adjacent arches,[2] or one of the four spaces between a circle within a square. They are frequently filled with decorative elements.

Meaning

[edit]There are four or five accepted and cognate meanings of the term spandrel in architectural and art history, mostly relating to the space between a curved figure and a rectangular boundary – such as the space between the curve of an arch and a rectilinear bounding moulding, or the wallspace bounded by adjacent arches in an arcade and the stringcourse or moulding above them, or the space between the central medallion of a carpet and its rectangular corners, or the space between the circular face of a clock and the corners of the square revealed by its hood. Also included is the space under a flight of stairs, if it is not occupied by another flight of stairs.[3]

In a building with more than one floor, the term spandrel is also used to indicate the space between the top of the window in one story and the sill of the window in the story above.[4] The term is typically employed when there is a sculpted panel or other decorative element in this space, or when the space between the windows is filled with opaque or translucent glass, in this case called "spandrel glass". In concrete or steel construction, an exterior beam extending from column to column usually carrying an exterior wall load is known as a "spandrel beam".[5]

In architectural ornamentation, the horizontal decorative elements that are hung over interior and exterior openings between the posts are called spandrels. They can be made of sawn out wood, ball-and-dowels, and spindles. Wooden ornamental spandrels are known as gingerbread spandrels. If they are in an arch form, they are called gingerbread arch spandrels.[6] The spandrels over doorways in perpendicular work are generally richly decorated. At Magdalen College, Oxford, is one which is perforated. The spandrel of doors is sometimes ornamented in the Decorated period, but seldom forms part of the composition of the doorway itself, being generally over the label.[7]

Domes

[edit]Spandrels can also occur in the construction of domes and are typical in grand architecture from the medieval period onwards. Where a dome needed to rest on a square or rectangular base, the dome was raised above the level of the supporting pillars, with three-dimensional spandrels called pendentives taking the weight of the dome and concentrating it onto the pillars.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Alfiz, an area encompassing the spandrels and voussoirs, sometimes also extending to the floor

- Cathedral architecture

- Spandrel (biology)

- Squinch

- Skeuomorph

References

[edit]- ^ less often spandril or splaundrel

- ^ Dutton, Denis (2009). The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9780199539420.

- ^ Emmitt, Stephen; Gorse, Christopher A. (2010). Barry's Introduction to Construction of Buildings. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 551. ISBN 9781118658581.

- ^ Ching, Francis D. K. (2014). Building Construction Illustrated. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 8.31. ISBN 9781118458341.

- ^ Bisharat, Keith A. (2004). Construction Graphics: A Practical Guide to Interpreting Working Drawings. Chichester: Wiley. p. 354. ISBN 9780471219835.

- ^ Russell, Jonathan (2005). 2006 national renovation & insurance repair estimator. Carlsbad, CA: Craftsman Book Co. p. 229. ISBN 9781572181649. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Spandril". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 593.