Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The Tyger

View on Wikipedia

| The Tyger | |

|---|---|

| by William Blake | |

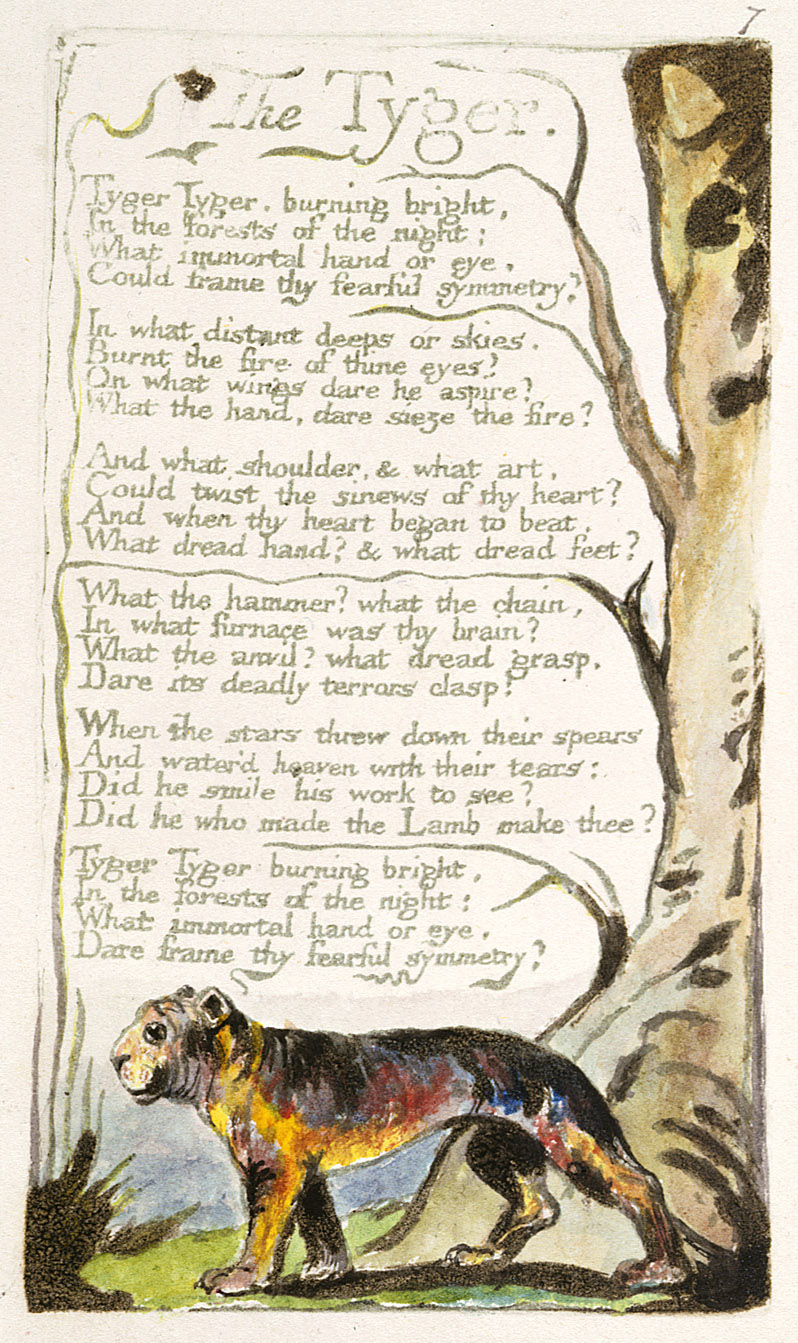

Copy A of Blake's original printing of The Tyger, 1794. Copy A is held by the British Museum. | |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Publication date | 1794 |

| Full text | |

The Tyger (also spelt The Tiger) is a poem by William Blake, published in 1794 in Songs of Experience, as Blake was rising to prominence as a poet. The poem is one of the most anthologised in the English literary canon;[1] it has been the subject of much literary criticism, and the inspiration for many musical settings and other adaptations.[2] It explores Christian religious paradigms prevalent in late-18th-century and early-19th-century England, questioning the intention and motivation behind God's creation of such disparate beings as the "Lamb" and the eponymous "Tyger."[3]

Songs of Experience

[edit]Songs of Experience was published in 1794 as a follow-up to Blake's 1789 Songs of Innocence.[4] The two books were published together under the merged title Songs of Innocence and of Experience, showing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul: the author and printer, W. Blake[4] featuring 54 illustrated plates. Blake reprinted the work throughout his life.[5] In some reprints, plates were arranged differently and certain poems were moved from Songs of Innocence to Songs of Experience. Of the original collection published during his life only 28 copies are known to exist, with an additional 16 published posthumously.[6] Only five of the poems from Songs of Experience appeared individually before 1839.[7]

Poem

[edit]Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?[8][9]

Structure

[edit]"The Tyger" is six stanzas in length with each stanza containing four lines. The meter of the poem is largely trochaic tetrameter. A number of lines, such as line four in the first stanza, fall into iambic tetrameter.[10]

The poem is structured around questions that the speaker poses concerning the "Tyger," including the phrase "Who made thee?" These questions often repeat instances of alliteration ("frame" and "fearful") and imagery (burning, fire, eyes) to frame the arc of the poem.

The first stanza opens the poem with a central line of questioning, stating "What immortal hand or eye, / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?". This direct address to the creature serves as a foundation for the poem's contemplative style as the "Tyger" cannot provide the speaker with a satisfactory answer. The second stanza questions the "Tyger" about where it was created, while the third stanza sees the focus move from the "Tyger" to its creator.[11] The fourth stanza questions what tools were used in the "Tyger's" creation. In the fifth stanza, the speaker wonders how the creator reacted to its "Tyger" and questions the identity of the creator themselves. Finally, the sixth stanza virtually repeats the poem's first stanza but rephrases the last line, altering its meaning: rather than question who or what "could" create the "Tyger", the speaker wonders who would "dare," effectively modifying the tone of the stanza to present as more of a confrontation than a query.

Themes and critical analysis

[edit]"The Tyger" is the sister poem to "The Lamb" (from "Songs of Innocence"), a reflection of similar ideas from a different perspective. In "The Tyger", there is a duality between beauty and ferocity, through which Blake suggests that understanding one requires an understanding of the other.

"The Tyger," as a work within the "Songs of Experience," was written as antithetical to its counterpart from the "Songs of Innocence" ("The Lamb") – antithesis being a recurring theme in Blake's philosophy and work. Blake argues that humankind's struggles have their origin in the dichotomies of existence. His poetry argues that truth lies in comprehending the contradictions between innocence and experience. To Blake, experience is not the face of evil, but rather a natural component of existence. Rather than believing in war between good and evil or heaven and hell, Blake believed that each man must first see and then resolve the paradoxes of existence and life.[11] Therefore, the questions posed by the speaker within "The Tyger" are intentionally rhetorical; they are meant to be answered individually by readers instead of brought to a general consensus.[12]

Colin Pedley and others have suggested that Blake may have been influenced in selecting the subject of this poem by the killing of a son of Sir Hector Munro by a tiger in December 1792.[13]

Musical versions

[edit]Blake's original tunes for his poems have been lost in time, but many artists have tried to create their own versions of the tunes.[14]

- Rebecca Clarke – "The Tiger" (1929–33)

- Benjamin Britten, in his song cycle Songs and Proverbs of William Blake (1965)

- Marianne Faithfull, in her song "Eye Communication" (1981) from the Dangerous Acquaintances album.

- Howard Frazin, in his song "The Tiger" for soprano and piano (2008), later expanded into an overture for orchestra, "In the Forests of the Night" (2009) commissioned by the Boston Classical Orchestra.[15]

- Duran Duran – "Tiger Tiger" (1983)

- Greg Brown, on the album Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1986)

- John Tavener – "The Tyger" (1987)[16]

- Tangerine Dream – the album Tyger (1987)

- Jah Wobble – "Tyger Tyger" (1996)

- Lauren Bernofsky – "The Tiger" (2002)

- Kenneth Fuchs – Songs of Innocence and of Experience: Four Poems by William Blake for Baritone, Flute, Oboe, Cello, and Harp (completed 2006)

- Herbst in Peking – "The Tyger and The Fly" (2014)

- Qntal – "Tyger" (2014)

- Mephisto Walz – "The Tyger"

- Elaine Hagenberg - "Tyger" for SATB Chorus and piano (2021) Hagenberg, Elaine (1 January 2021). "Tyger". Retrieved 14 November 2025.

Bob Dylan refers to Blake's poem in "Roll on John" (2012).[17]

Five Iron Frenzy uses two lines of the poem in "Every New Day" on Our Newest Album Ever! (1997).

Joni Mitchell uses two lines in her song about the music industry, the title track of her 1998 album Taming the Tiger.[18]

See also

[edit]

- Fearful Symmetry (disambiguation)

- Quasar, Quasar, Burning Bright

- Eye rhyme

- "The Stars My Destination" or "Tiger! Tiger!" (science fiction novel, 1956)

References

[edit]- ^ Eaves, p. 207.

- ^ Whitson and Whittaker 63–71.

- ^ Freed, Eugenie R. (3 July 2014). "'By Wondrous Birth': The Nativity of William Blake's 'The Tyger'". English Studies in Africa. 57 (2): 13–32. doi:10.1080/00138398.2014.963281. ISSN 0013-8398. S2CID 161470600.

- ^ a b Gilchrist 1907 p. 118

- ^ Davis 1977 p. 55

- ^ Damon 1988 p. 378

- ^ Bentley 2003 p. 148

- ^ Blake, William (1757–1827). Johnson, Mary Lynn; Grant, John Ernest (eds.). Blake's Poetry and Designs: Authoritative texts, Illuminations in Color and Monochrome, Related Prose, Criticism. W. W. Norton Company, Inc., 1979. pp. 21-22. ISBN 0393044874.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Blake, William (1757–1827). Erdman, David V. (ed.). The Complete Poetry and Prose (Newly revised ed.). Anchor Books, 1988. pp. 24-25. ISBN 0385152132.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Holman, Bob; Snyder, Margery (28 March 2020). "A Guide to William Blake's 'The Tyger'". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ a b Kazin, 41–43.

- ^ Hobsbaum, Philip (1964). "A rhetorical question answered: Blake's Tyger and its critics". Neophilologus. 48 (1): 151–155. doi:10.1007/BF01515534. ISSN 1572-8668. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Pedley, Colin (Summer 1990). "'Blake's Tiger and the Discourse of Natural History'" (PDF). Blake - an Illustrated Quarterly. 24 (1): 238–246.

- ^ #3746: "Songs of Experience": Music Inspired by Poetry of William Blake | New Sounds - Hand-picked music, genre free, retrieved 7 December 2017

- ^ "In the Forests of the Night – Howard Frazin". Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "John Tavener". musicsalesclassical.com. Chester Music. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ "Roll on John". Bob Dylan. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Joni Mitchell - Taming the Tiger - lyrics".

Sources

[edit]- Bentley, G. E. (editor) William Blake: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge, 1975.

- Bentley, G. E. Jr. The Stranger From Paradise. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-300-10030-2

- Damon, S. Foster. A Blake Dictionary. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1988.

- Davis, Michael. William Blake: A New Kind of Man. University of California Press, 1977.

- Eaves, Morris. The Cambridge Companion to William Blake, 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-78677-5

- Gilchrist, Alexander. The Life of William Blake. London: John Lane Company, 1907.

- Kazin, Alfred. "Introduction". The Portable Blake. The Viking Portable Library.

- Whitson, Roger and Jason Whittaker. William Blake and Digital Humanities:Collaboration, Participation, and Social Media. New York: Routledge, 2013. ISBN 978-0415-65618-4.

External links

[edit]- A Comparison of Different Versions of Blake's Printing of The Tyger at the William Blake Archive

- The Taoing of a Sound – Phonetic Drama in William Blake's The Tyger Detailed stylistic analysis of the poem by linguist Haj Ross

- wikiversity:English literary canon

The Tyger

View on GrokipediaBackground and Publication

Context in Blake's Works

"The Tyger" forms a central part of William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul, a unified illuminated collection first published in 1794. This work integrates poems from Blake's earlier Songs of Innocence (1789), which celebrate childlike purity and divine benevolence, with the new Songs of Experience that expose corruption and disillusionment. "The Tyger," included in the Experience section, directly challenges the innocence portrayed in "The Lamb" from the 1789 volume by juxtaposing a symbol of predatory ferocity against one of meek gentleness, thereby illustrating the collection's overarching structure as paired contraries that reveal the full spectrum of human existence.[6][7] Blake's visionary philosophy underpins this pairing, emphasizing contraries—opposites such as innocence and experience—as indispensable to human perception and spiritual growth. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–93), Blake articulates this view: "Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence." This doctrine informs the dualistic imagery of "The Tyger," where the creature's "fearful symmetry" represents the energetic, destructive force essential to creation, contrasting the passive harmony of innocence and urging readers to embrace both poles for a complete understanding of the divine and the self.[8][9] Within late 18th-century England, "The Tyger" embodies Blake's critique of institutionalized religion, which promoted an exclusively merciful God while suppressing acknowledgment of wrathful or ambiguous aspects of divinity, and of the burgeoning industrial society that mechanized human labor into something tyrannical. The poem's forge imagery—evoking hammers, anvils, and fiery furnaces—symbolizes the dehumanizing effects of industrialization during the early phases of the Industrial Revolution, transforming creation into a nightmarish, oppressive process akin to the era's exploitative factories.[10][11]Publication History

"The Tyger" first appeared in William Blake's Songs of Experience, published in 1794 as part of his illuminated printing process, where the poem was etched in relief on copper plates alongside its accompanying designs, then hand-colored by Blake and his wife Catherine.[12] This technique allowed Blake to produce small runs of unique copies, with Songs of Experience comprising 27 plates, including plate 42 dedicated to "The Tyger," printed in yellow ochre and further watercolored for variation across the approximately 30 known surviving copies.[13] The poem evolved from earlier drafts preserved in Blake's Notebook, a personal manuscript used primarily between 1792 and 1794, containing two versions of "The Tyger" on pages 108–109 (reversed), dated around 1793, which reveal revisions to phrasing and structure while retaining the distinctive archaic spelling "Tyger."[14] These drafts show Blake refining the poem's rhetorical intensity, transitioning from a more fragmented form to the symmetrical stanzas of the final version, without significant alterations to core imagery.[15] Following Blake's death in 1827, the poem gained wider circulation through posthumous editions, including the 1839 letterpress transcription of Songs of Innocence and of Experience published by W. Pickering and W. Newbery, which rendered the illuminated works in standard print but introduced minor typographical variations from the originals.[16] Later facsimiles, such as William Muir's 1885 color reproductions, aimed to replicate the etched and colored plates more faithfully, though early efforts often simplified the hand-applied hues.[17] Modern scholarly reprints, including the William Blake Trust's Trianon Press facsimiles from the 1950s onward and the digital editions of the William Blake Archive (launched 1996), prioritize accurate reproductions of specific copies, with textual emendations limited to correcting printer's errors in non-facsimile versions, such as occasional punctuation inconsistencies observed in 19th-century transcriptions.[18]Text and Illustrations

Poem Text

The Tyger Tyger Tyger, burning bright,In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry? In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire? And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat.

What dread hand? & what dread feet? What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp! When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee? Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry? This transcription reproduces the poem as it appears in the 1794 edition of Songs of Experience, with Blake's characteristic archaic spelling of "Tyger" and capitalization of nouns such as "Tyger" and "Lamb." The ampersand (&) is used in place of "and" in several lines, reflecting Blake's illuminated printing style.[1]

Blake's Illustrations

In William Blake's illuminated printing of Songs of Experience (1794), the plate for "The Tyger" (plate 42 in most copies) serves as the frontispiece for the poem, featuring a striking illustration below the text that captures the creature's majestic yet menacing presence. The image depicts a striped tiger striding to the left past a tall, vine-wrapped tree trunk that dominates the right margin, evoking the "forests of the night" referenced in the poem. This composition integrates the visual directly with the verse, printed in relief etching, where the raised lines allow for bold, intertwined text and imagery typical of Blake's innovative technique.[5] Blake employed color-printed relief etching, initially inked in olive-green or orange-brown tones, followed by meticulous hand-coloring with watercolors and shell gold to heighten the tiger's ferocity. In various copies, the tiger's fur is rendered in vibrant reds and golds, suggesting an inner fire that aligns with the poem's imagery of burning brightness and distant flames, while darker blues and blacks outline its form to convey a sense of terror and motion through dynamic, curving lines. These etching methods, combined with Blake's fluid line work, create an illusion of prowling energy, as the tiger's arched back and forward gaze imply relentless advance amid shadowy foliage.[12][19] The 1794 edition's illustrations position the tiger as a visual counterpart to the gentle lamb depicted in Songs of Innocence (1789), where the lamb appears in soft, serene whites amid pastoral meadows, emphasizing innocence against the tyger's bold, predatory symmetry that embodies experience. This duality in Blake's designs underscores the contrary states of the human soul without overt symbolism, relying on contrasting aesthetics to mirror the poems' thematic interplay.[9]Poetic Form

Meter and Rhyme

"The Tyger" is composed predominantly in trochaic tetrameter, consisting of four trochaic feet per line, where each foot features a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one, producing a rhythmic pattern that evokes the hammering of a forge.[20][21] This meter, as seen in the opening line "Tyger Tyger, burning bright," creates an insistent, pounding intensity that mirrors the poem's imagery of creation and power.[22] The poem follows an AABB rhyme scheme across its six quatrains, with rhyming couplets that provide a sense of propulsion and closure to each pair of lines.[20] Near-rhymes, such as "eye" and "symmetry" in the first stanza, introduce subtle tension and sonic dissonance, enhancing the poem's questioning tone without disrupting the overall regularity.[20] Meter variations include catalexis, the omission of the final unstressed syllable in many lines, resulting in a strong, truncated ending that emphasizes key words and heightens dramatic effect, as in "What immortal hand or eye."[22][20] This technique, combined with the trochaic rhythm, underscores the rhetorical questions that drive the poem's inquiry.[21]Repetition and Rhetoric

The poem employs a series of rhetorical questions to propel its interrogative structure, posing fourteen such inquiries across its twenty-four lines to evoke wonder and unease about the tiger's origins.[10] These questions, such as "What immortal hand or eye, / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?" in the opening stanza, recur throughout, with the first stanza repeated almost identically at the end but altered from "Could" to "Dare" in the final line, intensifying the sense of audacious creation.[1] Other examples include "What the hammer? what the chain, / In what furnace was thy brain?" which probe the tools and processes behind the beast's formation.[10] Anaphora reinforces this urgency through the repeated opening word "What" in successive lines and stanzas, as seen in the third and fourth stanzas: "And what shoulder, & what art, / Could twist the sinews of thy heart? / And when thy heart began to beat, / What dread hand? & what dread feet?"[23] This device mimics the relentless, hammering rhythm of a blacksmith at work, underscoring the poem's industrial imagery of forging.[10] The repetition of "Did he" in the penultimate stanza further exemplifies anaphora: "Did he smile his work to see? / Did he who made the Lamb make thee?" creating a parallel escalation that heightens the poem's paradoxical tension.[24] Parallelism structures the stanzas to progressively build from the mechanics of creation—evoking fire, anvil, and hammer—to mounting fear and awe, before circling back to the initial query in a modified form.[25] This mirroring between opening and closing stanzas frames the entire poem as an unresolved inquiry, with phrases like "burning bright" and "fearful symmetry" echoed to emphasize symmetry in form and dread in content.[1] The overall trochaic tetrameter supports this rhetorical escalation, lending a pounding cadence to the repeated interrogatives.[10]Themes

Creation and the Divine

In William Blake's "The Tyger," the titular creature symbolizes destructive energy forged by a divine "immortal hand or eye," embodying a forceful and awe-inspiring aspect of creation that evokes both terror and admiration.[26] This imagery portrays the tiger not merely as a natural beast but as a manifestation of primal, untamed power within the cosmos, crafted with deliberate intensity by a supernatural artisan.[27] Unlike the gentle, pastoral creation depicted in Blake's companion poem "The Lamb," which represents meekness and divine tenderness, the tiger highlights the fierce, revolutionary vitality inherent in the universe's design.[28] The poem's forge metaphors—an anvil, hammer, chain, and fiery furnace—evoke an industrial and apocalyptic process of creation, drawing from Blake's broader mythology where divine acts mirror human craftsmanship on a cosmic scale.[26] These elements suggest a blacksmith-like deity wielding tools of immense power to shape the tiger's "fearful symmetry," transforming raw, distant fires into a living emblem of energy and destruction.[29] In Blake's visionary framework, this forging process underscores the integration of creation and annihilation, where the divine hand dares to harness apocalyptic forces to produce beauty amid terror.[19] The rhetorical question "Did he smile his work to see?" probes the creator's emotional response, implying potential fear, regret, or ambivalence toward unleashing such a potent force into existence.[28] This interrogation raises profound doubts about divine intent, questioning whether the architect of a world blending sublime beauty with inherent terror views the outcome with approval or dread.[19] Blake's portrayal thus reveals a dual-natured God, capable of both nurturing innocence and igniting wrathful energy, reflecting the poet's complex theology of a multifaceted divinity.[27]Innocence Versus Experience

In William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience, "The Tyger" stands as a stark counterpart to "The Lamb," embodying the poet's philosophy of contraries where innocence represents purity and simplicity, while experience introduces fierce terror and moral complexity. The lamb, with its meekness and association with Christ-like gentleness, evokes a state of untroubled faith and harmony with the divine, whereas the tiger symbolizes the raw, destructive energy of experience that disrupts this idyllic vision. This opposition highlights Blake's belief that human development requires navigating these dual states, as the tiger's predatory power reflects the harsh realities of a fallen world.[30] The human speaker's response to the tiger's "fearful symmetry"—a phrase capturing its terrifying yet harmonious form—illustrates the psychological awakening brought by experience, transforming naive wonder into dread and questioning before natural and divine enigmas. This symmetry suggests an ordered ferocity in creation that innocence cannot comprehend, forcing a confrontation with the ambiguities of existence and the loss of childlike trust. Blake uses this to depict experience not merely as corruption but as a necessary expansion of perception, where awe mingles with fear to foster deeper insight into the soul's journey.[24][29] Through "The Tyger," Blake critiques rationalist ideologies like deism, which posit a distant, benevolent creator and simplistic origins, by emphasizing the poem's insistent query on whether the same divine force forged both the gentle lamb and the dreadful tiger. This rejection of tidy, mechanistic creation narratives underscores Blake's view that true understanding embraces the contraries of beauty and horror, rather than reducing them to rational harmony. The forging imagery, evoking a blacksmith's labor in distant "forests of the night," briefly nods to this divine craftsmanship while prioritizing the experiential terror it unleashes.[19][27]Critical Analysis

Historical Interpretations

During the 19th century, William Blake's poetry, including "The Tyger," garnered limited scholarly attention owing to his obscurity both during his lifetime and in the decades following his death in 1827. Blake's unconventional style and mystical themes contributed to his marginalization among contemporaries, with his works largely overlooked until the mid-century revival sparked by biographical efforts.[26] The first major analysis of "The Tyger" appeared in Alexander Gilchrist's 1863 biography Life of William Blake, which played a pivotal role in reintroducing Blake to the public. Gilchrist described the poem as one of Blake's finest achievements, noting its recognition even among early critics for its striking imagery and rhythmic intensity, and emphasizing its "dreadful" yet compelling portrayal of creation's fierce energy.[31][32] Victorian-era readings of the poem frequently adopted a moral lens, interpreting the tiger as an unambiguous symbol of evil or Satanic force, emblematic of sin and destruction in contrast to the innocence of Blake's "The Lamb." This binary view aligned with prevailing religious didacticism of the period, overlooking Blake's deliberate ambiguity in questioning the divine origins of both beauty and terror.[33] In the early 20th century, interpretations shifted toward more mythographic approaches, as seen in S. Foster Damon's seminal 1924 study William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols. Damon linked the tiger to Blake's mythological figure of Urizen, the embodiment of cold reason and restrictive law, suggesting the poem explores the tension between rational order and primal energy within Blake's broader cosmology.[34]Modern Perspectives

In the late 20th century, structuralist and archetypal criticism, influenced by Northrop Frye's work, reinterpreted "The Tyger" as part of Blake's mythic framework, emphasizing its role in apocalyptic imagery. Frye, in his analysis of Blake's symbolism, views the tiger as an embodiment of revolutionary and destructive energy within an archetypal structure drawn from biblical and mythological patterns, where the creature represents the fiery, transformative force of creation that challenges conventional moral dualisms.[35] This perspective positions the poem not merely as a query about divine benevolence but as a structural element in Blake's visionary cosmos, linking the tiger to broader cycles of fall and redemption in literature.[36] Ecocritical readings emerging in the 2000s have reframed the tiger as a potent symbol of untamed wilderness resisting the encroachments of industrialization and human dominance over nature. Scholar Kevin Hutchings argues that Blake's depiction of the tiger critiques the commodification of the natural world during the Romantic era, portraying the creature's "fearful symmetry" as an emblem of ecological vitality and the perils of anthropocentric exploitation, where the "forests of the night" evoke pre-industrial wildness threatened by emerging capitalist economies.[37] This interpretation highlights how the poem anticipates modern environmental concerns, with the tiger's creation myth underscoring the hubris of imposing order on chaotic, self-sustaining ecosystems. Feminist scholarship, particularly Anne K. Mellor's analyses, critiques the poem's divine imagery for reinforcing patriarchal narratives of creation. Mellor contends that the blacksmith-god forging the tiger exemplifies Blake's gendered mythology, where male agency dominates as a forceful, violent creator, while female elements remain absent or subordinated, mirroring broader Romantic-era myths that marginalize women in processes of genesis and power.[38] This reading exposes how the poem's rhetoric of "dread hand" and "deadly terrors" perpetuates a masculine sublime, critiquing the exclusion of feminine perspectives in Blake's otherwise revolutionary vision.[39] Postcolonial interpretations further explore the tiger as an exotic "other," reflecting British imperialism's fascination with and fear of colonial wildlife. In analyses of Romantic sublime poetry, the tiger—drawn from imperial encounters in India and Asia—symbolizes the terrifying allure of the non-European world, with its "burning bright" imagery evoking the Orient as a site of both wonder and threat under empire.[40] This lens reveals how Blake's poem, while subversive, inadvertently participates in constructing the colonized landscape as a dark, mysterious frontier to be mastered by the European gaze. Recent scholarship, including a 2023 study using digital humanities methods such as network analysis of Blake's symbolic motifs, has explored "The Tyger" within his illuminated prints. For instance, computational tools have quantified aspects of the poem's visual-aural synergies, revealing new layers of its revolutionary energy.[41]Cultural Impact

Musical Adaptations

Benjamin Britten composed a setting of "The Tyger" as the eighth song in his cycle Songs and Proverbs of William Blake, Op. 74, premiered in 1965 for baritone voice and piano. The accompaniment features a relentless, marching piano rhythm reminiscent of tolling bells and percussive hammering, evoking the divine forge described in the poem and underscoring its rhythmic intensity.[42] Britten's use of dissonant harmonies and stark dynamic contrasts heightens the sense of dread and awe, transforming the poem's interrogative structure into a dramatic vocal line that builds to explosive climaxes. Earlier in the 20th century, Rebecca Clarke created "The Tiger" (1929–1933) for soprano and piano, one of the first significant art song adaptations of the poem. Clarke's setting employs a sinuous melodic line and syncopated piano figures to mirror the tiger's fearful symmetry, capturing the poem's trochaic meter through propulsive rhythms that suggest both grace and ferocity.[43] The work's modal harmonies and vivid text painting emphasize the creative fire, making it a staple in the vocal repertoire for its concise yet evocative portrayal of Blake's imagery. In contemporary music, electronic pioneers Tangerine Dream released the album Tyger in 1987, a full-length homage to Blake's poetry that prominently features "The Tyger" through layered synthesizers and ambient soundscapes. The title track and surrounding pieces use pulsating electronic rhythms and ethereal drones to convey the poem's cosmic creation myth, with percussive sequences evoking the forge's intensity in a modern, otherworldly context.[44] This adaptation shifts the focus to immersive textures, highlighting the tiger as a symbol of primal energy amid the band's signature sequencer-driven propulsion. More recent interpretations include Patti Smith's 2011 live performance of "The Tyger" at the Wadsworth Atheneum, where she delivers the text in a raw, chanted style over minimal acoustic backing that amplifies the poem's incantatory rhythm. Smith's rendition emphasizes spoken-word delivery with subtle musical underscoring, drawing out the rhetorical questions to create a visceral sense of wonder and terror.[45] This approach aligns with broader 21st-century trends in blending poetry with ambient and folk elements, as seen in choral works like Elaine Hagenberg's "Tyger" (2019) for SATB voices and piano, which incorporates mixed meters and driving ostinatos to replicate the forge's percussive force.[46]Influence in Literature and Art

The poem "The Tyger" has exerted a profound influence on subsequent literature, particularly through its imagery of fierce, symmetrical creation and the divine's dual nature. In T.S. Eliot's 1920 poem "Gerontion," the line "Christ the tiger" directly evokes the predatory ferocity and paradoxical divinity of Blake's Tyger, portraying a Christ figure that embodies both salvation and destruction in a fragmented modern world.[33] This allusion underscores Eliot's modernist grappling with religious and existential tensions, mirroring Blake's interrogation of the creator's hand.[47] Ted Hughes, a 20th-century poet known for his vivid animal imagery, drew extensively on Blakean contraries in works like "The Jaguar" (1957), where the caged beast's restless energy parallels the Tyger's "burning bright" vitality and challenges human-imposed order.[48] Hughes' exploration of primal forces and the artist's role in confronting nature's ferocity reflects Blake's influence, as seen in his broader engagement with the poet's visionary symbolism to depict the raw, uncontrollable aspects of existence.[49] In visual art, "The Tyger" inspired Beat Generation figures, including Allen Ginsberg, who created pen drawings of the Tyger, such as one from 1993, influenced by his lifelong engagement with Blake's work and his 1948 visionary experience hearing Blake's voice.[50] Similarly, illustrator Michael Foreman contributed to the poem's legacy through his watercolor depictions in the 1982 edition of Songs of Innocence and of Experience, where the Tyger appears as a luminous, menacing form amid forest shadows, emphasizing its awe-inspiring symmetry for contemporary readers.[51] The poem's imagery has permeated popular culture, notably in body art, where "The Tyger" motifs—often featuring the archaic spelling and lines like "burning bright"—adorn tattoos symbolizing inner strength and creative duality, evoking Blake's themes in personal expressions of ferocity and beauty.[52] In film, Jim Jarmusch's Dead Man (1995) integrates "The Tyger" thematically, with protagonist William Blake (Johnny Depp) embodying the poem's wandering, transformative spirit during his journey through the American West, where recitations and visions highlight themes of death, rebirth, and divine symmetry.[53]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Marriage_of_Heaven_and_Hell