Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Time-division multiple access

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) |

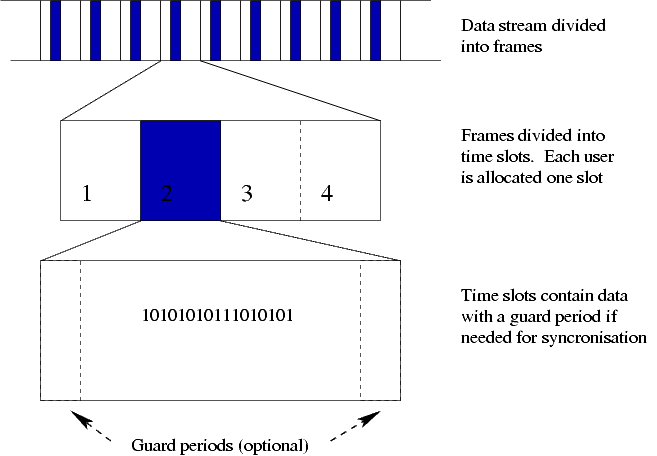

Time-division multiple access (TDMA) is a channel access method for shared-medium networks. It allows several users to share the same frequency channel by dividing the signal into different time slots.[1] The users transmit in rapid succession, one after the other, each using its own time slot. This allows multiple stations to share the same transmission medium (e.g. radio frequency channel) while using only a part of its channel capacity. Dynamic TDMA is a TDMA variant that dynamically reserves a variable number of time slots in each frame to variable bit-rate data streams, based on the traffic demand of each data stream.

TDMA is used in digital 2G cellular systems such as Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), IS-136, Personal Digital Cellular (PDC) and iDEN, in the Maritime Automatic Identification System,[2] and in the Digital Enhanced Cordless Telecommunications (DECT) standard for portable phones. TDMA was first used in satellite communication systems by Western Union in its Westar 3 communications satellite in 1979. It is now used extensively in satellite communications,[3][4][5][6] combat-net radio systems, and passive optical network (PON) networks for upstream traffic from premises to the operator.

TDMA is a type of time-division multiplexing (TDM), with the special point that instead of having one transmitter connected to one receiver, there are multiple transmitters. In the case of the uplink from a mobile phone to a base station this becomes particularly difficult because the mobile phone can move around and vary the timing advance required to make its transmission match the gap in transmission from its peers.

Characteristics

[edit]- Shares single carrier frequency with multiple users

- Non-continuous transmission makes handoff simpler

- Slots can be assigned on demand in dynamic TDMA

- Less stringent power control than CDMA due to reduced intra cell interference

- Higher synchronization overhead than CDMA

- Advanced equalization may be necessary for high data rates if the channel is "frequency selective" and creates intersymbol interference

- Cell breathing (borrowing resources from adjacent cells) is more complicated than in CDMA

- Frequency/slot allocation complexity

- Pulsating power envelope: interference with other devices

In mobile phone systems

[edit]2G systems

[edit]Most 2G cellular systems, with the notable exception of IS-95, are based on TDMA. GSM, D-AMPS, PDC, iDEN, and PHS are examples of TDMA cellular systems.

In the GSM system, the synchronization of the mobile phones is achieved by sending timing advance commands from the base station which instruct the mobile phone to transmit earlier and by how much. This compensates for the speed-of-light propagation delay. The mobile phone is not allowed to transmit for its entire time slot; there is a guard interval at the end of each time slot. As the transmission moves into the guard period, the mobile network adjusts the timing advance to synchronize the transmission.

Initial synchronization of a phone requires even more care. Before a mobile transmits there is no way to know the offset required. For this reason, an entire time slot has to be dedicated to mobiles attempting to contact the network; this is known as the random-access channel (RACH) in GSM. The mobile transmits at the beginning of the time slot as received from the network. If the mobile is near the base station, the propagation delay is short and the initiation can succeed. If, however, the mobile phone is just less than 35 km from the base station, the delay will mean the mobile's transmission arrives at the end of the time slot. In this case, the mobile will be instructed to transmit its messages starting nearly a whole time slot earlier so that it can be received at the proper time. Finally, if the mobile is beyond the 35 km cell range of GSM, the transmission will arrive in a neighbouring time slot and be ignored. It is this feature, rather than limitations of power, that limits the range of a GSM cell to 35 km when no special extension techniques are used. By changing the synchronization between the uplink and downlink at the base station, however, this limitation can be overcome.[citation needed]

3G systems

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

In the context of 3G systems, the integration of time-division multiple access (TDMA) with code-division multiple access (CDMA) and time-division duplexing (TDD) in the Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) represents a sophisticated approach to optimizing spectrum efficiency and network performance.[7]

UTRA-FDD (frequency division duplex) employs CDMA and FDD, where separate frequency bands are allocated for uplink and downlink transmissions. This separation minimizes interference and allows for continuous data transmission in both directions, making it suitable for environments with balanced traffic loads.[8]

UTRA-TDD (time division duplex), on the other hand, combines CDMA with TDMA and TDD. In this scheme, the same frequency band is used for both uplink and downlink, but at different times. This time-based separation is particularly advantageous in scenarios with asymmetric traffic loads, where the data rates for uplink and downlink differ significantly. By dynamically allocating time slots based on demand, UTRA-TDD can efficiently manage varying traffic patterns and enhance overall network capacity.[8][9]

The combination of these technologies in UMTS allows for more flexible and efficient use of the available spectrum, catering to diverse user demands and improving the adaptability of 3G networks to different operational environments.[8]

In wired networks

[edit]The ITU-T G.hn standard, which provides high-speed local area networking over existing home wiring (power lines, phone lines and coaxial cables) is based on a TDMA scheme. In G.hn, a "master" device allocates contention-free transmission opportunities (CFTXOP) to other "slave" devices in the network. Only one device can use a CFTXOP at a time, thus avoiding collisions. FlexRay protocol which is also a wired network used for safety-critical communication in modern cars, uses the TDMA method for data transmission control.

Comparison with other multiple-access schemes

[edit]In radio systems, TDMA is usually used alongside frequency-division multiple access (FDMA) and frequency-division duplex (FDD); the combination is referred to as FDMA/TDMA/FDD. This is the case in both GSM and IS-136 for example. Exceptions to this include the DECT and Personal Handy-phone System (PHS) micro-cellular systems, UMTS-TDD UMTS variant, and China's TD-SCDMA, which use time-division duplexing, where different time slots are allocated for the base station and handsets on the same frequency.

A major advantage of TDMA is that the radio part of the mobile-only needs to listen and broadcast for its own time slot. For the rest of the time, the mobile can carry out measurements on the network, detecting surrounding transmitters on different frequencies. This allows safe inter-frequency handovers, something which is difficult in CDMA systems, not supported at all in IS-95 and supported through complex system additions in Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS). This in turn allows for co-existence of microcell layers with macrocell layers.

CDMA, by comparison, supports "soft hand-off" which allows a mobile phone to be in communication with up to 6 base stations simultaneously, a type of "same-frequency handover". The incoming packets are compared for quality, and the best one is selected. CDMA's "cell breathing" characteristic, where a terminal on the boundary of two congested cells will be unable to receive a clear signal, can often negate this advantage during peak periods.

A disadvantage of TDMA systems is that they create interference at a frequency that is directly connected to the time slot length. This is the buzz that can sometimes be heard if a TDMA phone is left next to a radio or speakers.[10] Another disadvantage is that the "dead time" between time slots limits the potential bandwidth of a TDMA channel. These are implemented in part because of the difficulty in ensuring that different terminals transmit at exactly the times required. Handsets that are moving will need to constantly adjust their timings to ensure their transmission is received at precisely the right time because as they move further from the base station, their signal will take longer to arrive. This also means that the major TDMA systems have hard limits on cell sizes in terms of range, though in practice the power levels required to receive and transmit over distances greater than the supported range would be mostly impractical anyway.

Advantages of TDMA

[edit]TDMA (time-division multiple access) is a communication method that allocates radio frequency (RF) bandwidth into discrete time slots, allowing multiple users to share the channel in a sequential manner. This approach not only improves spectrum efficiency compared to analog systems but also offers several specific advantages that enhance communication quality and system performance.[11]

Advantages of TDMA

[edit]- Enhanced spectrum efficiency: TDMA maximizes the use of available bandwidth by allowing multiple users to share the same channel without overlapping. Each user is assigned a specific time slot, ensuring that the channel's capacity is fully utilized, thereby increasing overall system efficiency.

- Reduction of intersymbol interference: By assigning non-overlapping time slots to users, TDMA significantly reduces the risk of intersymbol interference. This interference occurs when signals from adjacent symbols overlap, leading to distortion and communication errors. The clear separation of time slots ensures that each symbol is transmitted distinctly, enhancing the reliability and clarity of the signal.

- Elimination of guard bands: Since adjacent channels in TDMA do not interfere with one another, there is no need for guard bands—unused frequency ranges that typically separate channels to prevent interference in other systems. This absence of guard bands allows for more efficient use of the available spectrum, providing additional capacity for more users.[12]

- Flexible rate allocation: TDMA supports dynamic allocation of time slots, allowing the system to adapt to varying user demands. Users can be assigned multiple time slots based on their data transmission needs, which can vary due to factors such as call duration or data requirements. This flexibility optimizes resource usage and can improve overall user experience.

- Low battery consumption: Unlike FDMA (frequency-division multiple access), which requires continuous transmission, TDMA operates in a noncontinuous manner. Each transmitter can be turned off when not in use, leading to significant power savings. This is particularly advantageous for mobile devices, as it prolongs battery life and reduces the need for frequent recharging.

- Simplified implementation: The time-based nature of TDMA simplifies the implementation of synchronization mechanisms between users. As users take turns using the channel, the system can more easily manage timing and coordination compared to more complex methods like CDMA (code-division multiple access), where signals overlap.[13]

- Scalability: TDMA systems can be scaled effectively to accommodate a growing number of users. As demand increases, additional time slots can be introduced without the need for significant changes to the existing infrastructure, making it easier to expand the network capacity.

- Improved quality of service (QoS): With the ability to assign specific time slots and manage user access dynamically, TDMA can enhance the overall quality of service. This can lead to reduced latency and increased throughput, ensuring that users experience reliable and efficient communication.

Disadvantages of TDMA

[edit]- Guard intervals: To prevent interference between adjacent TDMA slots, guard intervals must be added. These intervals, typically ranging from 30 to 50 microseconds, serve as buffers to ensure that transmissions do not overlap. However, this requirement for extra time means that the overall throughput of the system can be reduced, as valuable time is spent in guard intervals rather than transmitting data. This is particularly problematic in cellular networks where time and energy efficiency are paramount.[14]

- Energy consumption: While TDMA allows for some energy savings by turning off transmitters during idle periods, the inclusion of guard intervals can offset these benefits. The need for synchronization and the overhead associated with managing time slots can lead to increased energy consumption, particularly in scenarios where numerous users are competing for access to the channel. This can be a critical issue for mobile devices that rely on battery power.

- Synchronization challenges: TDMA requires precise synchronization between all users to ensure that each user transmits within their designated time slot. This can complicate system design and implementation, especially in dynamic environments where users may frequently join or leave the network. Maintaining synchronization becomes increasingly difficult as the number of users grows, leading to potential disruptions and communication errors if not managed effectively.

- Limited data rates: TDMA generally provides medium data rates compared to other multiple access techniques like CDMA (code-division multiple access). This limitation arises from the fixed time slot allocation, which can restrict the amount of data that can be transmitted in a given timeframe. As a result, users with higher data requirements may experience slower transmission speeds, leading to potential dissatisfaction and reduced performance for data-intensive applications.

- Moderate system flexibility: TDMA offers moderate flexibility in terms of user allocation and data transmission rates. Unlike CDMA, which allows for a more dynamic and adaptive use of bandwidth, TDMA's fixed time slot assignment can lead to inefficiencies. In scenarios where user demand fluctuates significantly, the rigid structure of TDMA may result in underutilization of resources, as not all time slots may be filled during periods of low demand.[15]

- Latency issues: Due to the time-sharing nature of TDMA, users may experience increased latency. When multiple users are connected, each must wait for their designated time slot to transmit data. In applications that require real-time communication, such as voice calls or video conferencing, this added delay can affect the quality of service, leading to lag and reduced responsiveness.

- Scalability constraints: While TDMA can accommodate a growing number of users by adding more time slots, this scalability is limited by the need for synchronization and the fixed nature of time slot assignments. As user demand increases, the system may face challenges in maintaining performance levels without significant investment in infrastructure upgrades or more complex management systems.[16]

Dynamic TDMA

[edit]In dynamic time-division multiple access (dynamic TDMA), a scheduling algorithm dynamically reserves a variable number of time slots in each frame to variable bit-rate data streams, based on the traffic demand of each data stream. Dynamic TDMA is used in:

- HIPERLAN/2 broadband radio access network.

- IEEE 802.16a WiMax

- Bluetooth

- Military Radios / Tactical Data Link

- TD-SCDMA

- ITU-T G.hn

- Simulation of TDMA / DTMA links

- MoCA

See also

[edit]- Duplex (telecommunications) – Communication flowing simultaneously in both directions

- Link 16 – NATO military tactical data exchange network that uses TDMA

References

[edit]- ^ Guowang Miao; Jens Zander; Ki Won Sung; Ben Slimane (2016). Fundamentals of Mobile Data Networks. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107143210.

- ^ "USCG How IAS Works". How IAS Works. Retrieved 10 March 2025.

- ^ Maine, K.; Devieux, C.; Swan, P. (November 1995). Overview of IRIDIUM satellite network. WESCON'95. IEEE. p. 483.

- ^ Mazzella, M.; Cohen, M.; Rouffet, D.; Louie, M.; Gilhousen, K. S. (April 1993). Multiple access techniques and spectrum utilisation of the GLOBALSTAR mobile satellite system. Fourth IEE Conference on Telecommunications 1993. IET. pp. 306–311.

- ^ Sturza, M. A. (June 1995). Architecture of the TELEDESIC satellite system. International Mobile Satellite Conference. Vol. 95. p. 214.

- ^ "ORBCOMM System Overview" (PDF).

- ^ Jagannatham, Aditya K. (2016). Principles of Modern Wireless Communication Systems. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9789339220037.

- ^ a b c "3G mobile systems" (PDF). Springer Nature. Springer, Boston, MA: 45–89. 2002. doi:10.1007/0-306-47795-5_3. ISBN 978-0-306-47795-9.

- ^ "ETSI TS 136 214 V14.3.0 (2017-10)" (PDF).

- ^ "Minimize GSM buzz noise in mobile phones". EETimes. July 20, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ "What is Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA)?". Networking. Retrieved 2024-10-28.

- ^ Kaur, Amritpreet; Kaur, Guneet (2017-03-15). "The Enhanced ECC Approach to Secure Code Dissemination in Wireless Sensor Network". International Journal of Computer Applications. 161 (7): 30–33. doi:10.5120/ijca2017913237. ISSN 0975-8887.

- ^ "Multiple access techniques: FDMA, TDMA, CDMA; system capacity comparisons", Mobile Wireless Communications, Cambridge University Press, pp. 137–160, 2004-12-16, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511811333.007, ISBN 978-0-521-84347-8, retrieved 2024-10-28

- ^ Nguyen, Kien; Golam Kibria, Mirza; Ishizu, Kentaro; Kojima, Fumihide (2019-02-14). "Performance Evaluation of IEEE 802.11ad in Evolving Wi-Fi Networks". Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing. 2019: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2019/4089365. ISSN 1530-8669.

- ^ "Multiple access techniques: FDMA, TDMA, CDMA; system capacity comparisons", Mobile Wireless Communications, Cambridge University Press, pp. 137–160, 2004-12-16, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511811333.007, ISBN 978-0-521-84347-8, retrieved 2024-10-28

- ^ Le Gouable, R. (2000). "Performance of MC-CDMA systems in multipath indoor environments. Comparison with COFDM-TDMA system". First International Conference on 3G Mobile Communication Technologies. Vol. 2000. IEE. pp. 81–85. doi:10.1049/cp:20000018. ISBN 0-85296-726-8.

Time-division multiple access

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

Time-division multiple access (TDMA) is a channel access method used in shared-medium networks, such as wireless and satellite communications, to enable multiple users or devices to share the same frequency channel without interference by subdividing the transmission time into discrete time slots assigned to each user.[6] In communication systems, the multiple access problem arises when multiple transmitters attempt to use a common medium, like a radio frequency band, simultaneously, which can lead to signal collisions and degraded performance unless coordinated through techniques like TDMA to ensure orderly access and avoid overlaps.[7] TDMA operates synchronously, meaning all participating stations are precisely timed to transmit only during their designated slots within a repeating frame structure, allowing efficient utilization of the shared bandwidth.[8] This synchronous assignment of fixed or dynamic time slots evolved as a solution to the limitations of earlier single-user or frequency-division systems, emerging prominently in the 1960s and 1970s through proposals in satellite communications. The first significant proposals for TDMA in this context date to 1965, when INTELSAT initiated studies and experiments, such as the MATE program field tests in 1966, to demonstrate its feasibility for global networks, marking a shift toward more efficient multiple access in commercial satellite systems.[9] While related to time-division multiplexing (TDM), which combines multiple signals over a single point-to-point link, TDMA specifically addresses multi-user access in broadcast or shared environments like satellites.[10] By the 1970s and 1980s, TDMA had become a foundational technique, building on these early satellite innovations to support broader applications in digital communications.[11]Operating Principles

Time-division multiple access (TDMA) operates by dividing the available time resource on a shared frequency channel into repeating frames, where each frame consists of multiple discrete time slots that are allocated to different users or devices. This structured division allows multiple users to access the channel sequentially without simultaneous transmission, enabling efficient sharing of the medium in systems such as cellular networks. The frame structure repeats periodically to maintain ongoing access, with the number of slots per frame determining the maximum number of concurrent users supported on that channel.[12] The core principle of TDMA relies on non-overlapping transmissions, wherein each assigned user transmits data only during its designated time slot, ensuring that signals from different users do not interfere with one another. This time-orthogonal approach prevents collisions and maintains signal integrity across the shared bandwidth. To achieve this, precise timing synchronization is essential among all participants, typically enforced through a centralized mechanism. In cellular configurations, a base station or central controller manages slot assignments dynamically based on user demand and availability, coordinating the allocation to optimize channel utilization.[6][12] The total channel capacity in a TDMA system is given by the equation where is the number of slots per frame, is the data rate per slot (in bits per slot), and is the frame duration (in seconds). This formula represents the aggregate bit rate supported by the channel, as it calculates the total bits transmitted across all slots in a frame divided by the time to transmit that frame. To derive this from underlying physical limits, the data rate per slot stems from the available bandwidth and slot efficiency (accounting for modulation, coding, and overhead), such that , where is the effective slot duration; ignoring guard times for simplicity, the total capacity approximates , highlighting how TDMA preserves the channel's inherent Shannon capacity while apportioning it temporally among users.[12] TDMA is particularly well-suited for supporting bursty traffic patterns, such as intermittent data transmissions in packet-switched networks, because unused slots can be reallocated dynamically to active users without wasting resources on continuous streams. This flexibility contrasts with constant-bit-rate applications, where idle slots during low-activity periods reduce overall efficiency but allow efficient handling of sporadic, variable-rate data like voice packets or sensor updates.[12]Technical Implementation

Frame and Slot Structure

In time-division multiple access (TDMA), the frame serves as the fundamental repeating time unit for channel allocation among multiple users, typically comprising a header for control and synchronization information, several user data slots, and optional signaling slots dedicated to network management tasks such as channel assignment. This structure ensures orderly access by dividing the available bandwidth temporally, allowing each assigned slot to carry burst transmissions from specific users without overlap. The header often includes unique word patterns for frame detection, while signaling slots handle overhead like power control commands. Each slot within a TDMA frame consists of key components to enable reliable transmission: a preamble for initial synchronization and receiver training, the main data payload conveying user information, and a trailer incorporating error-detection mechanisms such as cyclic redundancy checks (CRC) or parity bits. The preamble typically features known bit sequences to facilitate carrier recovery, timing alignment, and equalization at the receiver, while the trailer appends checksums to verify payload integrity post-demodulation. In burst-mode TDMA, these elements minimize inter-symbol interference and support efficient demodulation, with the payload size varying based on modulation and coding schemes. A representative example is the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), where the TDMA frame divides into 8 equal slots, each with a duration of approximately 577 μs (precisely 15/26 ms), yielding a total frame length of 4.615 ms (60/13 ms). These durations derive from the system's bit rate of 270.833 kbps (1625/6 kbps), which transmits 156.25 bits per slot—including overhead—optimized to fit the 200 kHz channel spacing in the 900 MHz frequency band using Gaussian minimum shift keying (GMSK) modulation with a bandwidth-time product of 0.3, ensuring spectral efficiency while accommodating guard periods and propagation delays.[13][14] TDMA systems vary in slot sizing to balance predictability and adaptability; fixed-slot designs, like in GSM, maintain constant durations for simplified scheduling, whereas variable-slot approaches dynamically adjust lengths to match traffic loads, potentially increasing utilization but complicating synchronization. Slot overhead—encompassing preambles, trailers, and guard times—typically consumes 10-30% of slot capacity, directly impacting throughput; for instance, in GSM's 156.25-bit slot, with approximately 42 bits of overhead (including training sequence, tail bits, and guard period), the effective payload is 114 bits, or about 73%, highlighting the trade-off between robustness and efficiency in overhead-intensive environments.[13][15] In satellite TDMA applications, frames are frequently aggregated into superframes—grouping multiple consecutive frames—to establish longer-period timing for higher-layer functions like resource reallocation and encryption key updates, enhancing overall system stability in high-latency links.[16]Synchronization and Guard Times

In time-division multiple access (TDMA) systems, bit-level synchronization is essential to ensure that transmitters and receivers maintain precise alignment of their clocks, typically to within a few microseconds, preventing signal overlap and enabling accurate slot detection. This precision is critical because even minor timing drifts can cause bursts from different users to collide at the receiver, degrading signal integrity in shared channels. For instance, in wireless LAN implementations of TDMA, timing errors are bounded to under 7 μs to support reliable packet transmission across short slots of hundreds of microseconds.[17][18] Several techniques are employed to achieve this synchronization, tailored to the network type. In satellite TDMA systems, reference bursts transmitted from a primary station provide a timing reference, allowing secondary stations to adjust their clocks by measuring arrival times and compensating for delays. For cellular networks, base stations broadcast periodic beacon signals containing synchronization information, enabling mobile devices to align their transmissions. In global navigation satellite systems-integrated setups, such as inter-satellite links, GPS receivers offer absolute time references to maintain network-wide coherence without relying solely on relative measurements. These methods collectively ensure that all nodes operate within the frame structure's predefined slot timing. Guard times serve as short idle periods inserted between adjacent TDMA slots to accommodate propagation delays and hardware switching transients, thereby preventing inter-slot interference. These periods allow signals from distant or mobile users to arrive without overlapping into the next slot and provide time for transmitters to turn off and receivers to activate. Typical guard time lengths range from 10 to 30 symbols, depending on the modulation rate and network scale; for example, in some broadcast bus TDMA protocols, they are set to 30-50 μs to handle variations in user distances from the base station.[19][20] The necessity of guard times can be derived from the signal propagation model, where the guard time must satisfy , with representing the maximum variation in one-way propagation delay across users and the combined transmitter-receiver switching time. Propagation delay for a user at distance is , where is the speed of light; variations arise from differences in due to mobility or network geometry, such as in multihop packet radio networks where differential delays can reach tens of microseconds. The switching time accounts for hardware transients, typically on the order of symbol durations, ensuring the receiver captures the full burst without preamble loss. This inequality ensures that the earliest arriving signal from the next slot does not encroach on the current one, derived by considering the round-trip timing adjustments needed for burst alignment at the central receiver.[20][21] Poor synchronization in TDMA leads to co-channel interference, where misaligned bursts from users on the same frequency overlap, causing bit errors and reduced capacity. This was a significant challenge in early TDMA pilot deployments, such as initial cellular trials in the late 1980s, where timing inaccuracies from uncompensated propagation variations resulted in frequent interference in urban environments. These issues were largely resolved through the adoption of adaptive timing control, including closed-loop feedback mechanisms that dynamically adjust burst offsets based on measured delays, improving reliability in standards like IS-54.[22][23][24]Applications

Wireless Systems

Time-division multiple access (TDMA) has been a cornerstone of wireless communication systems, particularly in second-generation (2G) cellular networks, where it enabled efficient sharing of radio resources among multiple users. The Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), launched commercially in Finland in 1991, exemplifies TDMA's prominent role in 2G, utilizing an 8-slot frame structure with each time slot lasting approximately 577 µs, allowing up to eight users to share a 200 kHz carrier frequency for voice transmission at 13 kbit/s per user via the full-rate speech codec.[13][25] This design facilitated digital voice services in the 1990s, marking a shift from analog systems and supporting widespread mobile telephony adoption.[26] In the evolution to third-generation (3G) systems, TDMA played a partial role through the TD-CDMA variant in the Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS), specifically for time-slotted uplink operations in the time division duplex (TDD) mode, which combined TDMA with code division multiple access (CDMA) to handle asymmetric traffic. However, TD-CDMA saw limited adoption due to challenges in interference management and spectrum efficiency compared to the dominant frequency division duplex (FDD) WCDMA mode, resulting in its use primarily for niche applications like fixed wireless access rather than broad mobile deployments.[27] By the transition to 4G Long-Term Evolution (LTE) and 5G New Radio (NR), TDMA was largely phased out in favor of orthogonal frequency-division multiple access (OFDMA), which better supports high-data-rate broadband services, though legacy 2G TDMA persists mainly in rural and developing regions as of late 2025 for basic voice and low-bandwidth applications, despite ongoing network sunsets.[28] Beyond cellular evolution, TDMA remains integral to low-data-rate wireless systems such as Digital Enhanced Cordless Telecommunications (DECT) for cordless phones, employing a 10 ms TDMA frame with 24 slots to enable short-range voice and data communications in home and office environments. In Internet of Things (IoT) contexts, TDMA underpins protocols like Time-Slotted Channel Hopping (TSCH) in IEEE 802.15.4e for low-power, low-rate sensor networks, ensuring collision-free access in resource-constrained scenarios. Additionally, enhancements like the General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) in GSM leveraged multi-slot allocation over TDMA frames, allowing mobile stations to aggregate multiple slots for higher data rates up to 114 kbit/s downlink in eight-slot configurations, bridging voice-centric 2G toward packet data.[29][30]Wired and Satellite Systems

In wired networks, time-division multiple access (TDMA) principles have been applied in early broadband coaxial systems to enable efficient multiplexing of voice and data services, such as in TDMA-based telephone service architectures that integrate broadcast and communication over shared cable infrastructure.[31] Token ring networks, developed in the 1980s, incorporate time-slot arbitration through a circulating token mechanism that allocates transmission rights sequentially among nodes, providing controlled access similar to TDMA principles to prevent collisions in shared-medium local area networks.[32] Satellite communications extensively employ TDMA to coordinate multiple earth stations accessing a shared transponder, particularly in geostationary (GEO) systems like those defined by INTELSAT standards, where burst-mode transmissions allow stations to send data in predefined time slots.[33] This approach accommodates propagation delays of up to 250 ms in GEO orbits, ensuring bursts from distant terminals arrive without overlap at the satellite.[34] In low Earth orbit (LEO) systems, such as Iridium's constellation, TDMA supports efficient resource allocation across non-geostationary satellites for global coverage.[35] A typical satellite TDMA frame structure begins with acquisition and control bursts transmitted by a reference station to establish initial synchronization, followed by traffic bursts from other terminals, enabling precise timing adjustments amid varying propagation paths.[36] By permitting remote terminals to transmit high-rate bursts intermittently rather than continuously, TDMA reduces the required size and cost of central hub equipment while optimizing bandwidth usage.[37] In military satellite communications (SATCOM), TDMA provides secure slotted access through demand-assigned multiple access (DAMA) protocols, ensuring interference-free transmission for tactical networks.[38] These adaptations amplify synchronization challenges due to orbital dynamics and long distances, necessitating robust reference burst mechanisms.[39]Comparisons and Variants

With Other Multiple Access Methods

Time-division multiple access (TDMA) divides the available bandwidth into time slots assigned to different users, contrasting with frequency-division multiple access (FDMA), which allocates discrete frequency bands to users within the same time frame.[40] FDMA, prevalent in early analog systems like first-generation mobile networks, requires guard bands between channels to mitigate adjacent-channel interference, while TDMA employs guard times between slots to account for synchronization inaccuracies and propagation delays.[40] TDMA aligns more naturally with digital modulation schemes, as seen in second-generation systems, whereas FDMA suits analog transmissions due to its simpler frequency separation without timing precision.[40]| Aspect | FDMA | TDMA |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Division | Frequency bands | Time slots |

| Interference Mitigation | Guard bands (frequency separation) | Guard times (temporal separation) |

| Suitability | Analog systems (e.g., 1G) | Digital systems (e.g., 2G GSM) |