Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Transbaikal

View on Wikipedia

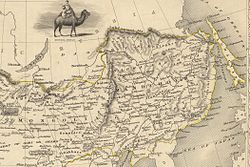

Transbaikal, Trans-Baikal, Transbaikalia (Russian: Забайка́лье, romanized: Zabaykal'ye, IPA: [zəbɐjˈkalʲjɪ]), or Dauria (Даурия, Dauriya) is a mountainous region to the east of or "beyond" (trans-) Lake Baikal at the south side of the eastern Siberia and the south-western corner of the Far Eastern Russia.

The steppe and wetland landscapes of Dauria are protected by the Daursky Nature Reserve, which forms part of a World Heritage Site named "Landscapes of Dauria".

Geography

[edit]Dauria stretches for almost 1,000 km from north to south from the Patom Plateau and North Baikal Highlands to the Russian state borders with Mongolia and China. The Transbaikal region covers more than 1,000 km from west to east from Lake Baikal to the meridian of the confluence of the Shilka and Argun Rivers. To the west and north lies the Irkutsk Oblast; to the north the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), to the east the Amur Oblast. Oktyabrsky (Октябрьский) village, Amur Oblast, near the Russia-China border is a large site of uranium mining and processing facilities.[1]

Part of the area is protected by the Dauria Nature Reserve.[2]

Fauna and flora

[edit]The region has given its name to various animal species including Daurian hedgehog, and the following birds: Asian brown flycatcher (Muscicapa daurica), Daurian jackdaw, Daurian partridge, Daurian redstart, Daurian starling, Daurian shrike and the red-rumped swallow (Hirundo daurica). The Mongolian wild ass (Equus hemionus hemionus) is extinct in the region.

The common name of the famous Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) as well as that of the Dahurian buckthorn (Rhamnus davurica) are also derived from the same source.

History

[edit]

The ancient proto-Mongol slab-grave culture occupied the area around Lake Baikal in the Transbaikal territory.[3]

In 1667, Gantimur opened Transbaikalia and the country on the Amur River to the influence of the Tsardom of Russia.[citation needed]

In Imperial Russia, Dauria itself became an oblast - the Transbaikal Oblast (Russian: Забайкальская область), established in 1851, with its capital at Nerchinsk, later at Chita. It became part of the short-lived Far Eastern Republic between 1920 and 1922.

As of 2020[update], the administration of the historic Transbaikalia includes Buryatia and the Zabaykalsky Krai; the area makes up nearly all of the territory of these two federal subjects.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Shandala N, Filonova A, Titov A, Isaev D, Seregin V, Semenova V, and Metlyaev EG (2009), Radiation situation nearby the uranium mining facility, Environmental section poster P.9, 54th Annual Meeting of the Health Physics Society, 12–16 July 2009, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

- ^ "The exhibition "Iris Russia"". flower-iris.ru. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ History of Mongolia, Volume I, 2003.

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch (1888). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (9th ed.). pp. 509–511.

- Kropotkin, Peter; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–170.