Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

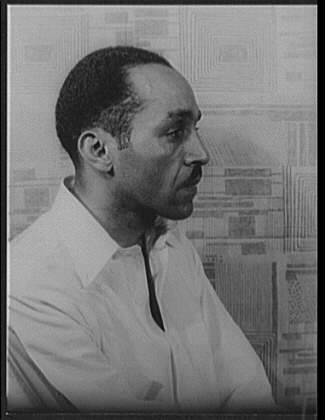

Willard Motley

View on Wikipedia

Willard Francis Motley (July 14, 1909 – March 4, 1965) was an American author. Beginning as a teenager, Motley published a column in the African-American oriented Chicago Defender newspaper under the pen-name Bud Billiken. He worked as a freelance writer, and later founded and published the Hull House Magazine and worked in the Federal Writers' Project. Motley's first and best known novel was Knock on Any Door (1947), which was made into a movie of the same name (1949).

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Early life and career

[edit]Motley was born and grew up in the Englewood neighborhood, South Side, Chicago, in one of the few African-American families residing in that neighborhood at the time. The family was Catholic.[2] His grandfather, Archibald Motley Sr. was a Pullman porter who raised him as a son. His grandmother Mary ("Mae") was a homemaker.[2] Motley graduated from Lewis-Champlain grammar school, and Englewood High School.[3] He and the noted artist Archibald Motley Jr. were raised as brothers, although Archibald was in fact Willard's uncle; Willard's mother, Florence (known as "Flossie") moved to New York City after he was born and left him to be raised by her parents.[2]

When he was 13, Willard was hired by Robert S. Abbott to write a children's column called "Bud Says," under the pen name, "Bud Billiken," for the Chicago Defender.[2][4] Later, Willard traveled to New York, California and the western states, earning a living through various menial jobs, as well as by writing for the radio and newspapers. During this period, he served a jail sentence for vagrancy in Cheyenne, Wyoming.[5] Returning to Chicago in 1939, he lived near the Maxwell Street Market, which was to figure prominently in his later writing. He became associated with Hull House, and helped found the Hull House Magazine, in which some of his fiction appeared. In 1940 he wrote for the Works Progress Administration Federal Writers' Project along with Richard Wright and Nelson Algren.[6]

In 1947, his first novel, Knock on Any Door, appeared to critical acclaim. A work of gritty naturalism, it concerns the life of Nick Romano, an Italian-American altar boy who turns to crime because of poverty and the difficulties of the immigrant experience; it is Romano who says the famous phrase: "Live fast, die young and have a good-looking corpse!"[7][8][9] It was an immediate hit, selling 47,000 copies during its first three weeks in print. In 1949, it was made into a movie starring Humphrey Bogart. In response to critics who charged Motley with avoiding issues of race by writing about white characters, Motley said: "My race is the human race."[10] His second novel, We Fished All Night (1948),[11] was not hailed as a success, and after it appeared Motley moved to Mexico to start over. His third novel, Let No Man Write My Epitaph, picks up the story of Knock on Any Door. Columbia Pictures made it into a movie in 1960. Ella Fitzgerald's music for the film was released on the album Ella Fitzgerald Sings Songs from the Soundtrack of "Let No Man Write My Epitaph".

Criticism

[edit]According to the citation statement for the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame awards, "Motley was criticized in his life for being a black man writing about white characters, a middle-class man writing about the lower class, and a closeted homosexual writing about heterosexual urges. But those more kindly disposed to his work, and there were plenty, admired his grit and heart....Chicago was more complicated than just its racial or sexual tensions, and as a writer his exploration was expansive...."[12] Motley was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2014.

Death and legacy

[edit]On March 4, 1965, Motley died of intestinal gangrene in Mexico City, Mexico.[3][4] Some sources say he was 52, giving his birthdate as July 14, 1912;[3][5] however, the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature at the Chicago Public Library, which holds a selection of his papers, notes his date of birth as July 14, 1909.[4] After his death, his adopted son, Sergio Lopez, said, "He let this illness go too long before getting proper medical treatment."[5] Lopez also said that Motley had been working on a novel tentatively titled My House Is Your House.[5]

His final novel, posthumously published in 1966, was Let Noon Be Fair.[13] Since 1929, Chicago has held an annual Bud Billiken Parade and Picnic (acknowledging his pen name during his early career at the Chicago Defender) on the second Saturday of August.[14] The parade travels through the city's Bronzeville, Grand Boulevard and Washington Park neighborhoods on the south side. The bulk of Motley's archive is held in the University Libraries, Rare Books and Special Collections, at Northern Illinois University.[15]

Bibliography

[edit]Novels

[edit]- Knock on Any Door, D. Appleton-Century Company, 1947; Northern Illinois University Press, 1989, ISBN 9780875805436

- We Fished All Night, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1951

- Let No Man Write My Epitaph, Random House, 1958

- Let Noon Be Fair, 1966; Pan Books, 1969 – published posthumously.

Nonfiction

[edit]- The Diaries of Willard Motley, Iowa State University Press, 1979 – published posthumously, ISBN 9780813807058

Letters

[edit]- Willard F. Motley Papers, 1939–1951; Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, Chicago Public Library, 2002

References

[edit]- ^ Pitts, Vanessa (March 28, 2013). "Motley, Willard (1909–1965) – The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Willard Motley | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Granger, Bill (June 26, 1994). "Willard Motley – A Writer Of Brutal Honesty". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b c "Willard F. Motley Papers". www.chipublib.org. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Willard Motley Dies in Mexico; Author of 'Knock on Any Door': Chicagoan, Representative of Naturalistic School, Was 52 -- Also Wrote 'Epitaph'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ "Willard Motley Papers". Mapping the Stacks: A Guide to Black Chicago's Hidden Archives. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ The first occurrence of the quote in the novel, in Chapter 35: "'Live fast, die young and have a good-looking corpse!' he said with a toss of his head. That was something he had picked up somewhere, and he'd say it all the time now." Motley, Willard (1989). Knock on Any Door (1989 paperback ed.). Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780875805436.

- ^ Similar phrases had appeared in print earlier. See "Live Fast, Die Young, and Leave a Beautiful Corpse". Quote Investigator. January 31, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Moser, Whet (October 23, 2012). "'Live Fast, Die Young, Leave a Good-Looking Corpse': Coined by a Chicago Writer". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Kogan, Rick (April 3, 2015). "Remembering forgotten writer Willard Motley". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Compare Luke 5:5 (KJV) "And Simon answering said unto him, Master, we have toiled all the night and have taken nothing: nevertheless at thy word I will let down the net."

- ^ "Willard Motley". The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame: 2013 Nominees. Chicago Writers Association. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Fleming, Robert E. (March 9, 2001). "Willard Motley: Let Noon be Fair". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Cabello, Tristan. "Queer Writers: Willard Motley · Queer Bronzeville". outhistory.org. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ "Willard Motley Papers, 1922-1966 | Northern Illinois University". archon.lib.niu.edu. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Encyclopedia of World Biography entry on Willard Motley.

- The Literary Encyclopedia's entry on Knock on Any Door.

- Finding aid for the Willard Motley Papers at Northern Illinois University.

- Part of his early life is retold in the 1948 radio drama "Mike Rex (Willard Motley)", a presentation from Destination Freedom written by Richard Durham.