Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Two-port network.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Two-port network

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Two-port network

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

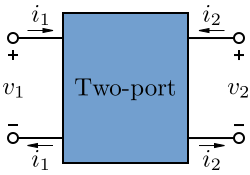

A two-port network is an electrical circuit or device characterized by two pairs of terminals, called ports, where each port consists of a pair of nodes allowing for the measurement of voltage and current, facilitating the analysis of energy transfer between an input and an output.[1] These networks model linear, passive systems such as resistors, capacitors, inductors, transformers, and transmission lines, assuming no internal power sources and often exhibiting reciprocity, where the response is symmetric between ports.[2]

The behavior of a two-port network is described using sets of parameters that relate the port voltages and currents, enabling simplified analysis of complex circuits. Common parameter sets include impedance (Z) parameters, which express voltages in terms of currents (e.g., ); admittance (Y) parameters, the inverse relating currents to voltages; hybrid (H) parameters, mixing voltage and current for transistor modeling; and transmission (ABCD) parameters, ideal for cascading networks by relating input to output variables.[3] These parameters can be interconverted and are particularly useful for networks that are reciprocal (where ) or symmetrical.[2]

Two-port networks are fundamental in electrical engineering for applications including amplifier design, filter synthesis, signal processing, and microwave systems, where they allow modular analysis of interconnected components in series, parallel, or cascade configurations. In RF and high-frequency contexts, they extend to scattering (S) parameters to account for wave propagation, aiding in the characterization of antennas, couplers, and transmission lines.[2]

The primary advantage of ABCD-parameters lies in their suitability for cascading multiple two-port networks, such as in ladder networks or transmission lines, where the overall matrix is obtained by simple matrix multiplication of individual ABCD matrices from right to left in the signal flow direction.[29] This multiplicative property facilitates efficient analysis of complex systems without solving the full circuit equations each time.[30]

Fundamentals

Definition and Graphical Representation

A two-port network is an electrical circuit or device characterized by four terminals grouped into two pairs, each pair forming a port that connects to external circuits.[4] The network is modeled as a black box, where the internal components—such as resistors, capacitors, inductors, or dependent sources—are encapsulated, and the external behavior is described solely by the voltages and currents at the ports.[5] Each port consists of two terminals, with the voltage defined as the potential difference across them and the current as the net flow into the port, ensuring no direct connection between the ports except through the internal network.[6] The variables associated with the ports are the input port voltage and current at port 1, and the output port voltage and current at port 2.[5] Port 1 is conventionally the input, where enters the positive terminal and is measured with the positive polarity at that terminal.[4] For port 2, the output, is defined as leaving the positive terminal to indicate power flow direction, with across the terminals and positive polarity at the exit point.[6] This directionality aligns with the passive sign convention, where positive power is absorbed when voltage and current have the same polarity reference.[6] Graphically, a two-port network is often represented in a chain diagram, showing port 1 on the left with its terminals facing right toward port 2 on the right, emphasizing the sequential input-output flow like links in a chain.[4] In distributed systems, such as transmission lines, it is depicted as a line segment connecting the two ports at opposite ends, modeling wave propagation between them.[4] Another representation is the lattice diagram, which illustrates a symmetrical configuration with series and shunt elements arranged in a crossed (diagonal) and parallel structure, useful for balanced networks.[7] Two-port networks are typically assumed to be linear, meaning responses are proportional to excitations and superposition applies; time-invariant, with parameters unchanging over time; and composed of lumped elements, where component sizes are negligible compared to signal wavelengths unless specified as distributed.[6] They may be passive, containing only energy-dissipating or -storing elements, or active, incorporating sources for amplification.[8]Applications in Circuit Analysis

Two-port networks originated in the early 20th century as a fundamental tool in electrical engineering, particularly for analyzing telephone lines and transmission systems during the expansion of long-distance telephony. Pioneered by researchers at Bell Laboratories, such as George A. Campbell, the theory addressed challenges in signal attenuation and multiplexing over extended cables, with early applications focusing on loading coils and wave filters to improve voice transmission quality.[9] Campbell's seminal work on physical theory of electric wave filter circuits, published in 1922, laid the groundwork for modeling linear networks as interconnected two-ports, enabling systematic design of frequency-selective components for telephony.[10] This historical development, building on transmission line theory from the late 19th century, transformed circuit analysis by providing a modular framework for cascading network sections, as exemplified in the use of ABCD parameters for telephone cable modeling.[11] In practical electronics, two-port networks play a central role in simplifying the analysis of amplifiers, filters, transmission lines, and matching networks by representing complex subsystems as black boxes with defined input and output relationships. For amplifiers, transistors are commonly modeled as two-port devices using hybrid parameters to calculate voltage gain, input/output impedances, and stability factors, facilitating broadband design in communication systems. In filter design, two-port representations allow engineers to predict frequency response and insertion loss, essential for separating signal bands in analog multiplexing, as seen in early telephony filters and modern RF front-ends. Transmission lines, such as coaxial cables or microstrip lines, are analyzed using scattering or ABCD parameters to account for reflections and attenuation, ensuring signal integrity over high-speed links. Matching networks, often composed of lumped elements or distributed lines, employ two-port models to optimize power transfer and minimize standing wave ratios in RF systems.[12] The benefits of this approach lie in its modularity, which permits treating subsystems independently while enabling precise calculations of overall gain, impedance matching, and stability in cascaded circuits. By isolating internal complexities, two-port analysis reduces computational demands and supports superposition for linear systems, making it invaluable for predicting performance without full circuit simulation. For instance, in transistor-based amplifiers, the two-port model reveals potential oscillations through stability criteria like the Rollett factor, guiding design iterations. In RF circuits, it ensures signal integrity by quantifying return loss and insertion gain, critical for minimizing distortions in wireless transceivers.[13] Examples abound in electronics, such as modeling a common-emitter transistor amplifier as a two-port to derive h-parameters for small-signal analysis, which directly informs bias and feedback configurations. In RF engineering, two-port networks characterize antenna matching circuits to achieve 50-ohm interfaces, enhancing efficiency in radar and cellular systems. These techniques extend to modern applications in integrated circuits, where two-port models simulate on-chip amplifiers and filters in CMOS processes for low-power 5G transceivers. In microwave engineering, scattering parameters describe high-frequency behavior of waveguides and monolithic microwave integrated circuits (MMICs), supporting designs up to millimeter waves. Additionally, in control systems, actuators and sensors are represented as two-ports to analyze feedback loops and dynamic responses, aiding stability in robotic and automotive applications.[14][15]General Properties

Linearity and Superposition

In two-port networks, linearity refers to the property where the output voltages and currents are directly proportional to the input excitations, satisfying both homogeneity and additivity. Homogeneity implies that scaling an input by a constant factor scales the corresponding output by the same factor, while additivity means that the response to a sum of inputs equals the sum of the individual responses.[16][17] This linearity enables the application of the superposition theorem, which states that in a linear two-port network with multiple independent sources, the total response at any port is the sum of the responses produced by each source acting alone, with all other sources deactivated (voltage sources shorted and current sources opened).[16] Superposition simplifies analysis by allowing decomposition of complex excitations into simpler components.[17] Mathematically, linearity manifests in the linear algebraic relations between port voltages and currents , such as in impedance form or in admittance form, where and are constant matrices independent of the excitation levels.[17] These relations hold for networks composed of linear elements like resistors, inductors, and capacitors.[16] As a consequence, linearity facilitates parameter extraction by applying independent excitations to each port sequentially, leveraging superposition to isolate individual effects without interference from other inputs.[6] It is particularly valid in small-signal analysis, where signals are sufficiently small to avoid nonlinear behavior.[18] However, linearity breaks down in networks containing nonlinear elements such as diodes or transistors, where responses do not scale proportionally; in such cases, small-signal linearization approximates the behavior around an operating point using equivalent linear models.[17][18]Reciprocity and Symmetry

In two-port networks, reciprocity refers to the property where the transfer characteristics are identical in both directions, meaning the response at one port due to excitation at the other is the same as the reverse scenario. Mathematically, this is expressed in impedance parameters as and in admittance parameters as , indicating that the open-circuit voltage at port 1 due to a current at port 2 equals the open-circuit voltage at port 2 due to the same current at port 1.[1] This condition holds for passive, linear, time-invariant networks composed of elements like resistors, capacitors, inductors, and transmission lines, provided there are no active devices or materials that introduce directionality, such as gyrotropic media.[19] The reciprocity theorem underlying this property was formalized by Hendrik Lorentz in his work on electromagnetic theory, with key extensions applied to network analysis in the early 20th century. Symmetry in a two-port network describes a balanced configuration where the input and output ports exhibit equivalent behavior, allowing interchange without altering the overall response. This is characterized by in impedance parameters and in hybrid parameters, implying a mirrored structure that equalizes self-impedances or admittances at both ports.[20] A symmetric network often combines reciprocity with this port equivalence, leading to simplified parameter matrices where the determinant of the hybrid matrix equals unity as a condition of symmetry. Such symmetry is common in balanced transformers and certain filter topologies, facilitating easier analysis and implementation. To verify reciprocity experimentally, one method involves interchanging the source and load positions between ports and measuring the transfer ratios, such as the ratio of output voltage to input current; equality confirms the property. For instance, applying a current source at port 1 and measuring open-circuit voltage at port 2, then swapping and repeating, yields identical ratios in reciprocal networks.[5][1] This testing approach leverages the invariance of excitation-response ratios under port reversal, as defined in standard network theory.[21] Reciprocity and symmetry have significant implications for network design, particularly in passive components like filters and transformers, where they enable bidirectional signal handling and reduce complexity in modeling symmetric responses. In filter design, reciprocal properties ensure consistent performance regardless of signal direction, aiding in the development of bandpass filters with uniform insertion loss. Similarly, in transformers, symmetry simplifies impedance matching and core modeling, enhancing efficiency in power and signal applications. Non-reciprocal two-port networks, by contrast, violate these conditions and are realized using active elements like transistors or ferrite materials in microwave devices; examples include circulators, which direct signals unidirectionally via ferrite-based nonreciprocal phase shifts under magnetic bias.Parameter Sets

Impedance Parameters (Z-Parameters)

The impedance parameters, or Z-parameters, characterize a two-port network by expressing the port voltages as linear functions of the port currents under open-circuit conditions at the respective ports. These parameters are particularly useful for networks analyzed with current excitations and series connections, as they directly yield impedances in ohms. The defining equations are: where and are the voltages across ports 1 and 2, and and are the currents entering those ports.[22] The individual Z-parameters are obtained by setting one current to zero: with (port 2 open-circuited), with , with (port 1 open-circuited), and with . This measurement approach reflects open-circuit impedance conditions, making Z-parameters ideal for scenarios where ports are not shorted during characterization.[23][24] Physically, represents the driving-point input impedance at port 1 when port 2 is open, indicating how the network loads the source at the input. Similarly, is the driving-point output impedance at port 2 when port 1 is open, showing the network's output loading effect. The off-diagonal terms and quantify the transfer impedances: is the ratio of output voltage to input current with output open (forward transfer), and is the ratio of input voltage to output current with input open (reverse transfer). These interpret as voltage ratios influenced by the network's internal coupling.[22][24] In matrix notation, the Z-parameters compactly represent the network as: This form facilitates analysis of series combinations, where the total Z-matrix is the sum of individual matrices, and all elements share units of ohms for dimensional consistency.[25] For reciprocal networks, , reflecting symmetric energy transfer between ports as discussed in network symmetry properties. The advantages of Z-parameters include their suitability for series-connected networks, where parameters add directly, and their intuitive impedance interpretation for voltage-current analyses in lumped circuits.[25]Admittance Parameters (Y-Parameters)

Admittance parameters, commonly referred to as Y-parameters or short-circuit admittance parameters, describe the behavior of a linear two-port network by expressing the port currents as linear functions of the port voltages. These parameters are obtained by applying voltages to one port while short-circuiting the other port to measure the resulting currents. The approach is particularly suited to networks where short-circuit conditions are practical for measurement or analysis.[26] The fundamental equations defining the Y-parameters are: Here, and represent the currents entering the positive terminals of ports 1 and 2, respectively. In matrix notation, this relationship is: The elements are specifically defined as , , , and , with short-circuit conditions applied as indicated.[26] Physically, is the input admittance observed at port 1 with port 2 short-circuited, is the output admittance at port 2 with port 1 short-circuited, is the forward transadmittance measuring the output current response to input voltage under shorted output conditions, and is the reverse transadmittance capturing the input current response to output voltage under shorted input conditions. All Y-parameters have units of siemens (S), reflecting their admittance nature.[26] Y-parameters offer advantages in scenarios involving parallel configurations of two-port networks, where the overall Y-matrix is simply the sum of the individual matrices, simplifying analysis of shunt-connected systems. For reciprocal networks, the condition holds.[26] Consider a shunt admittance network consisting of a parallel RC combination with admittance connected between the ports (with common ground). The Y-parameters for this configuration are: Thus, the matrix is: At high frequencies, where is large and the capacitive term dominates, , so , demonstrating the network's behavior as primarily capacitive under short-circuit conditions.[27]Hybrid Parameters (H-Parameters)

Hybrid parameters, also known as h-parameters, provide a characterization of linear two-port networks by expressing the input voltage and output current in terms of the input current and output voltage. This mixed representation combines impedance-like and admittance-like terms, making it particularly suitable for analyzing active devices such as transistors where the input is driven by current and the output by voltage. The defining equations are: In matrix notation, this is written as: The individual parameters are determined under specific terminal conditions: , the short-circuit input impedance; , the open-circuit reverse voltage ratio; , the short-circuit forward current gain; and , the open-circuit output admittance.[1] Physically, represents the input impedance with the output port short-circuited, reflecting how the network loads the source; quantifies the reverse voltage feedback from output to input with the input open, indicating isolation or coupling; is the forward current transfer ratio under shorted output, akin to a current amplification factor; and denotes the output admittance with the input open, showing the network's output loading effect. These interpretations facilitate practical measurements and circuit design, especially at low frequencies where direct voltage and current probes are feasible.[1] The h-parameters originated in the early 1950s as part of efforts to standardize transistor characterization amid rapid advancements in semiconductor technology following the invention of the point-contact transistor in 1947. Initially referred to as series-parallel parameters due to their mixed series (impedance) and parallel (admittance) nature, the term "hybrid" was coined by D. A. Alsberg in 1953 during discussions on transistor metrology at the IRE Convention, emphasizing their blend of voltage and current variables for amplifier analysis. This development occurred during the transition from vacuum tube circuits, where similar parameter sets were explored, to solid-state devices, with standardization efforts by the IRE and AIEE in 1954 promoting their use in data sheets for consistency across manufacturers. A representative application is the common-emitter (CE) configuration of a bipolar junction transistor (BJT) amplifier, where h-parameters are derived from the small-signal hybrid-pi model to predict performance. In this setup, the input port corresponds to the base-emitter junction driven by base current , and the output to the collector with voltage . The forward current gain (denoted in CE notation) approximates the transistor's small-signal current gain , defined as , where typically ranges from 50 to 300 for silicon BJTs and directly influences the amplifier's voltage and power gains. The other parameters, such as (input resistance, often 1–5 kΩ) and (reverse voltage feedback, usually small like 10^{-4}), are obtained by applying test signals to the pi-model equivalents, enabling straightforward calculation of overall circuit metrics like input impedance and output resistance without full simulation.[28]Inverse Hybrid Parameters (G-Parameters)

The inverse hybrid parameters, or g-parameters, characterize a two-port network by expressing the input current and output voltage as linear functions of the input voltage and output current . The defining equations are: In matrix form, this relationship is represented as: The individual parameters are defined under specific termination conditions: (input admittance with the output port open-circuited), (reverse current transfer ratio with the input port short-circuited), (forward voltage transfer ratio with the output port open-circuited), and (output impedance with the input port short-circuited). These parameters have clear physical interpretations in circuit analysis: represents the driving-point admittance at the input port under open-circuit conditions at the output, quantifies the reverse transfer of current from the output to the input under short-circuit conditions at the input, measures the forward transfer of voltage from the input to the output under open-circuit conditions at the output, and denotes the driving-point impedance at the output port under short-circuit conditions at the input. The off-diagonal elements and are dimensionless, while has units of admittance (siemens) and has units of impedance (ohms). The g-parameters are particularly advantageous for analyzing transistor-based amplifiers where the input is driven by a current source and the output delivers voltage, such as in common-base configurations of bipolar junction transistors (BJTs), as they naturally align with low input impedance and high output impedance characteristics.[25] For reciprocal networks, which contain no dependent sources or non-reciprocal elements like gyrators, the condition holds, ensuring symmetry in the transfer characteristics.[25] As an example, consider a common-base BJT amplifier analyzed using the small-signal hybrid-π model, where the base is grounded, the input is applied to the emitter (port 1), and the output is taken from the collector (port 2). The parameters are derived from the model elements: transconductance (where is the thermal voltage), base-emitter resistance (with the common-emitter current gain), and output resistance . Approximating for high and neglecting base-width modulation initially, , (where is the common-base current gain, yielding ), , and . Including the Early effect via , the forward voltage gain is large under conditions where output resistance dominates and current transfer is nearly ideal, illustrating the configuration's utility for high voltage gain in buffered applications.[25]Transmission Parameters (ABCD-Parameters)

Transmission parameters, also known as ABCD-parameters, describe a two-port network by expressing the input voltage and current (at port 1) in terms of the output voltage and current (at port 2), which is particularly useful for analyzing networks where signal flow is predominantly from input to output, such as in cascade or chain configurations.[29] The defining equations are: where and are the voltage and current at the input port, and are those at the output port (with directed away from the network), and A, B, C, D are the transmission parameters.[30] These parameters are determined under specific conditions: A is the ratio when the output port is open-circuited (), B is when the output port is short-circuited (), C is with , and D is with .[29] In matrix form, the relationships are compactly represented as: The physical interpretations of these parameters reflect their roles in network behavior: A represents the voltage ratio or transfer function with an open output, B acts as a transfer impedance (with units of ohms), C serves as a transfer admittance (with units of siemens), and D denotes the current ratio with a shorted output.[30][29] A and D are dimensionless, while B and C carry impedance and admittance dimensions, respectively.[30] For reciprocal networks, which satisfy the reciprocity theorem (no dependent sources and passive elements), the determinant of the ABCD matrix equals unity: .[31] Symmetric networks, where the ports are interchangeable, further require .[30] These properties are summarized in the following table:| Property | Condition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reciprocity | Holds for passive, linear networks without non-reciprocal elements.[31] | |

| Symmetry | Applies when the network is symmetric about its midplane.[30] |