Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Annulene

View on Wikipedia

Annulenes are monocyclic hydrocarbons that contain the maximum number of non-cumulated or conjugated double bonds ('mancude'), and their derivatives. They have the general formula CnHn (when n is an even number) or CnHn+1 (when n is an odd number). The IUPAC accepts the use of 'annulene nomenclature' in naming carbocyclic ring systems with 7 or more carbon atoms, using the name '[n]annulene' for the mancude hydrocarbon with n carbon atoms in its ring,[1] though in certain contexts (e.g., discussions of aromaticity for different ring sizes), smaller rings (n = 3 to 6) can also be informally referred to as annulenes. Using this form of nomenclature 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene is [8]annulene and benzene is [6]annulene (and occasionally referred to as just 'annulene').[2][3]

The discovery that [18]annulene possesses a number of key properties associated with other aromatic molecules was an important development in the understanding of aromaticity as a chemical concept.

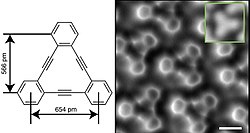

In the related annulynes, one double bond is replaced by a triple bond.

Aromaticity

[edit]| n | aromaticity |

|---|---|

| 4 | antiaromatic |

| 6 | aromatic |

| 8 | nonaromatic |

| 10 | nonaromatic |

| 12 | weakly antiaromatic |

| 14 | weakly aromatic |

| 16 | nonaromatic[4] |

| 18 | aromatic |

Annulenes may be aromatic ([6]annulene (benzene) and [18]annulene), non-aromatic ([8] and [10]annulene), or anti-aromatic (cyclobutadiene, [4]annulene). Cyclobutadiene is the only annulene with considerable antiaromaticity, since planarity is unavoidable. With [8]annulene, the molecule takes on a tub shape that allows it to avoid conjugation of double bonds. [10]Annulene is of the wrong size to achieve a planar structure: in a planar conformation, ring strain due to either steric hindrance of internal hydrogens (when some double bonds are trans) or bond angle distortion (when the double bonds are all cis) is unavoidable. Thus, it does not exhibit appreciable aromaticity.

When the annulene is large enough, [18]annulene for example, there is enough room internally to accommodate hydrogen atoms without significant distortion of bond angles. [18]Annulene possesses several properties that qualify it as aromatic.[5] However, none of the larger annulenes are as stable as benzene, as their reactivity more closely resembles a conjugated polyene than an aromatic hydrocarbon.

In general, charged annulene species of the form [C4n+2+qH4n+2+q]q (n = 0, 1, 2, ...; q = 0, ±1, ±2; 4n + 2 + q ≥ 3) are aromatic, provided a planar conformation can be achieved. For instance, C5H−5, C3H+3, and C8H2−8 are all known aromatic species.

Gallery

[edit]-

Cyclobutadiene ([4]annulene)

-

Benzene ([6]annulene)

-

Cyclooctatetraene ([8]annulene)

-

Cyclodecapentaene ([10]annulene)

-

Cyclododecahexaene ([12]annulene)

-

Cyclotetradecaheptaene ([14]annulene)

-

Cyclooctadecanonaene ([18]annulene)

-

Cyclodocosahendecaene ([22]annulene)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "annulene". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00368

- ^ Ege, S. (1994) Organic Chemistry:Structure and Reactivity 3rd ed. D.C. Heath and Company

- ^ Dublin City University Annulenes Archived April 7, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Johnson, Suzanne M.; Paul, Iain C.; King, G. S. D. (1970). "[16]Annulene: the crystal and molecular structure". Journal of the Chemical Society B: Physical Organic: 643–649. doi:10.1039/j29700000643. ISSN 0045-6470.

- ^ Oth, Jean F. M.; Bünzli, Jean-Claude; De Julien De Zélicourt, Yves (1974-11-06). "The Stabilization Energy of [18] Annulene. A thermochemical determination". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 57 (7): 2276–2288. Bibcode:1974HChAc..57.2276O. doi:10.1002/hlca.19740570745. ISSN 0018-019X.

External links

[edit]- NIST Chemistry WebBook - [18]annulene

- Structure of [14] and [18]annulene

Annulene

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Nomenclature

Definition

Annulenes are a class of monocyclic hydrocarbons that feature the maximum possible number of non-cumulated, conjugated double bonds arranged in a ring, forming what is termed a mancude structure. This configuration ensures a fully conjugated π-electron system encircling the cycle, distinguishing annulenes from other cyclic polyenes that may have interruptions in conjugation or cumulative double bonds, such as those in allene-like arrangements.[10][16] The general molecular formula for neutral annulenes with an even number of carbon atoms, denoted as , is , reflecting the alternating single and double bonds that saturate the valences without side chains or substituents. This formula arises from the structural requirement of complete alternation, where each carbon contributes one hydrogen atom in the neutral form.[10] The term "annulene" originates from the Latin word annulus, meaning "ring," combined with the suffix "-ene" to indicate the presence of double bonds, emphasizing the cyclic and unsaturated nature of these compounds. The term was coined in 1962 by chemist Franz Sondheimer.[4][18]Nomenclature

Annulenes are named using the convention annulene, where n denotes the number of carbon atoms in the ring, applicable systematically for rings with seven or more carbons.[10] For smaller rings, traditional names are preferred, such as benzene for [2]annulene.[10] This nomenclature reflects the monocyclic, mancude hydrocarbon structure with a fully conjugated system of double bonds, adhering to the general formula C_nH_n for even n or C_nH_{n+1} for odd n.[10] The even-numbered annulenes typically feature alternating single and double bonds to achieve complete conjugation without cumulation, as seen in cyclooctatetraene ([10]annulene).[19] Hydrocarbon annulenes form the core of this class, but derivatives incorporating additional unsaturation, such as dehydroannulenes, are named by prefixing the number and "dehydro-" to indicate the triple bonds, for example, tetradehydro[20]annulene for a [20]annulene with four acetylenic units. Analogs with heteroatoms, known as heteroannulenes, follow heterocyclic nomenclature rules rather than the annulene parent, often using replacement prefixes like "aza-" or "oxa-" in systematic names, though the term "heteroannulene" is used descriptively in literature.[20] IUPAC guidelines for annulenes specify numbering to assign the lowest possible locants to the double bonds, starting from one end of the conjugated system.[22] Isomers differing in double-bond configurations are distinguished using stereodescriptors (E) and (Z), placed in parentheses with appropriate locants before the name. This ensures precise identification of all-cis or mixed configurations critical for properties like planarity, with all-cis forms often preferred in aromatic examples.Historical Development

Early Concepts

The concept of annulenes originated in the 19th century with benzene, recognized retrospectively as [2]annulene, which was first isolated in 1825 by Michael Faraday from the oily residue of illuminating gas production.[23] In 1865, August Kekulé proposed its cyclic structure consisting of six carbon atoms arranged in a ring with alternating double bonds, providing the foundational model for understanding cyclic conjugated hydrocarbons.[13] In the early 20th century, efforts extended these ideas to larger cyclic polyenes, with Richard Willstätter achieving the first synthesis of cyclooctatetraene, or [10]annulene, in 1911 through a multi-step process starting from pseudopelletierine.[25] This compound's unexpected instability and non-planar tub-like conformation challenged prevailing assumptions about cyclic conjugation.[26] Theoretical frameworks for these systems advanced with Johannes Thiele's partial valence theory introduced in 1899, which posited that unsaturated bonds in conjugated chains, including cyclic ones, involve residual affinities leading to electron delocalization and enhanced stability in even-membered rings like benzene.[6] Thiele's ideas suggested that all fully conjugated cyclic polyenes should exhibit similar aromatic character, prompting Willstätter's synthesis of cyclooctatetraene as a test case, which ultimately revealed limitations in this hypothesis.[28] Prior to Erich Hückel's molecular orbital-based rule in 1931, annulenes such as benzene and cyclooctatetraene served as key experimental models for probing the elusive nature of aromatic stability, highlighting the role of ring size, planarity, and conjugation in chemical reactivity.[29]Key Syntheses and Advances

The synthesis of [6]annulene in 1959 marked a pivotal milestone in annulene chemistry, achieved by Franz Sondheimer and colleagues through oxidative coupling of linear triacetylenic precursors followed by partial hydrogenation. This method yielded the first stable, fully conjugated [4n+2]π-electron annulene, confirming its predicted aromaticity with a diatropic ring current observed in NMR spectroscopy. The approach not only validated Hückel's rule for larger systems but also established a template for subsequent annulene constructions using metal-catalyzed coupling reactions.[30] In the following decades, efforts expanded to [5]annulene and [13]annulene, synthesized in the early 1960s and mid-1960s, respectively, also via Sondheimer's oxidative coupling strategies on polyyne precursors. Unlike the nearly planar [6]annulene, X-ray crystallography and computational analyses revealed that [5]annulene adopts a saddle-shaped, non-planar conformation due to transannular steric repulsions, while [13]annulene exhibits bond alternation and tub-like distortion, underscoring the challenges of maintaining planarity in [4n]π systems.[31][32] These developments highlighted how ring strain and conformational flexibility influence antiaromatic character and instability in medium-sized annulenes.[33] Recent advances have pushed annulene topologies beyond classical Hückel geometries, with the 2006 synthesis of the first Möbius [13]annulenes by Rainer Herges and coworkers using stereoselective olefin metathesis and aromatization of bridged precursors.[34] These twisted structures, featuring a single half-turn along the π-perimeter, demonstrated enhanced aromatic stabilization for 4n π electrons, as evidenced by paratropic shifts in NMR and lower energy compared to untwsited isomers.[34] In 2025, the report of planar metalloannulenes, such as osmium-centered [35]annulenes constructed via cycloaddition and ligand assembly, introduced metal-mediated planarity and delocalization, bridging annulene and coordination chemistry with confirmed aromaticity through electrochemical and spectroscopic studies.[36] Theoretical progress has paralleled these syntheses, with quantum mechanical computations evolving from early Hückel molecular orbital models to density functional theory (DFT) applications predicting stability in larger annulenes. Seminal ab initio studies in the 1970s elucidated bond alternation in [5]annulene, while modern DFT analyses, such as those using B3LYP functionals, have modeled paratropicity and conformational energies in [37]annulene and beyond, revealing how electron correlation stabilizes delocalized states against Peierls distortion.[38] These simulations have guided synthetic design by forecasting viable topologies for expanded annulenes up to systems.[39]Structure and Classification

General Molecular Structure

Annulenes are monocyclic hydrocarbons featuring a fully conjugated system of alternating single and double bonds, with the general formula CₙHₙ for even-numbered rings.[40] This structure consists of n carbon atoms forming a closed loop, where each carbon atom is sp²-hybridized, contributing to a planar or near-planar geometry in many cases. The pi-electron system arises from the p-orbitals perpendicular to the ring plane, with each double bond providing two pi electrons, resulting in a total of n pi electrons for an annulene.[41] The molecular geometry of annulenes varies between planar and non-planar configurations, influenced by ring strain and steric interactions. In smaller rings, significant angle strain prevents planarity, as the internal bond angles deviate substantially from the ideal 120° for sp² carbons, leading to tub-shaped or twisted conformations to alleviate distortion. Larger annulenes, however, can adopt more planar structures where bond angles approach 120°, minimizing strain and allowing for better orbital overlap in the conjugated system; these ring size effects are explored further in classifications by ring size.[41] In non-aromatic annulenes, bond lengths exhibit clear alternation, with single bonds measuring approximately 1.47 Å and double bonds around 1.34 Å, reflecting localized pi bonding similar to acyclic polyenes. This alternation diminishes in cases of delocalization, where bonds become more uniform, though complete equalization is rare beyond small rings like benzene.[41] Medium-sized annulenes, such as [20]- to [13]annulenes, display cis-trans isomerism due to the configuration around their double bonds, which introduces conformational flexibility and allows for dynamic interconversions. These stereoisomers can adopt twisted or Möbius-like conformations during isomerization, facilitating low-energy pathways for cis-to-trans shifts without breaking bonds.[37]Classification by Ring Size

Annulenes are classified by the number of carbon atoms in their cyclic polyene structure, denoted as annulene where n is even for fully conjugated neutral systems, influencing their strain, planarity, and overall feasibility. This categorization highlights how ring size affects molecular geometry and behavior, with smaller rings dominated by angle strain and larger ones by transannular interactions or synthetic challenges.[41] Small annulenes, with n=6 to 10, exhibit high angle strain due to deviations from the ideal 120° sp² bond angles in smaller rings, making planarity difficult beyond n=6. The [2]annulene, benzene, achieves a stable planar D_{6h} structure, minimizing strain and enabling full π-delocalization. In contrast, [10]annulene adopts a tub-shaped conformation to alleviate antiaromatic destabilization and angle strain, rendering it non-planar and non-aromatic. Similarly, [4]annulene is highly strained and unstable in planar form, often distorting to reduce internal hydrogen repulsion.[41][30][43] Medium annulenes, encompassing n=12 to 16, experience reduced angle strain compared to smaller rings but face increased steric hindrance from internal hydrogens, leading to non-planar conformations. For instance, [5]annulene prefers a saddle-shaped geometry to balance bond alternation and transannular strain, preventing full planarity despite satisfying Hückel's 4n+2 electron count. This distortion compromises conjugation and stability, with [20]annulene and [13]annulene also showing conformational flexibility that hinders aromatic character.[41][43][44] Large annulenes, with n≥18, benefit from lower angle strain owing to greater ring flexibility, allowing closer approaches to planarity and better satisfaction of aromaticity criteria when electron counts align with Hückel's rule. The [6]annulene exemplifies this, adopting a nearly planar D_{6h}-like structure that supports diatropic ring currents and aromatic stability. However, even in this category, subtle distortions can arise from van der Waals repulsions among internal protons.[41][38][30] Overall trends show that increasing n diminishes angle strain, facilitating planarity in larger systems, but elevates synthetic difficulties due to the need for precise control over bond alternation and conformational locking; only even n values are typically considered for neutral annulenes to ensure complete alternation of single and double bonds. These size-dependent geometric features directly impact stability, with planarity being crucial for aromatic delocalization as explored in aromaticity criteria.[41][30]Aromaticity Criteria

Application of Hückel's Rule

Hückel's rule, formulated by Erich Hückel in 1931, establishes a key theoretical framework for evaluating the aromatic character of conjugated cyclic molecules, including annulenes. The rule posits that a planar, monocyclic system with continuous conjugation of p orbitals exhibits aromatic stability if it contains π electrons, where is a non-negative integer; conversely, systems with π electrons are anti-aromatic, displaying destabilization, while those not fitting either category are non-aromatic. This electron-counting criterion arises from molecular orbital theory, where the configuration leads to a closed-shell ground state with all bonding orbitals filled, enhancing stability through delocalization.[45] In the context of annulenes, which are idealized models of such systems due to their uniform hydrocarbon composition, the number of π electrons directly corresponds to the ring size in annulene, as each sp²-hybridized carbon atom donates one electron to the π system.[46] For instance, [20]annulene possesses 12 π electrons, satisfying the condition with , thus predicted to be anti-aromatic.[46] The general aromaticity condition can be expressed as: where denotes the total π electrons (equal to for neutral annulenes with even ). This equivalence simplifies predictions: annulenes are aromatic when for integer , and anti-aromatic when .[45] The rule's applicability is confined to monocyclic, planar, and fully conjugated frameworks, making annulenes exemplary test cases for probing its validity without heteroatomic or substituent complications.[46] Deviations from planarity, often arising in larger rings, can modulate the effective conjugation and thus the manifestation of aromaticity predicted by the rule.[47]Factors Influencing Planarity and Stability

The planarity of annulenes, essential for achieving effective π-orbital overlap and aromatic stabilization, is primarily governed by angle strain arising from deviations in the internal bond angles from the ideal 120° expected for sp²-hybridized carbon atoms. In medium-sized annulenes such as [4]annulene, the planar conformation imposes significant angle strain, leading to elongated C-C-C angles of approximately 144° and favoring non-planar tub or saddle-shaped geometries to minimize this distortion.[39] In contrast, larger annulenes like [6]annulene experience relatively low angle strain due to their expanded ring size, resulting in a slightly puckered C_2 symmetric structure close to planarity, with the idealized D_{6h} form being a nearby stationary point that supports delocalized conjugation.[38] Steric repulsion, particularly transannular interactions between hydrogen atoms in all-cis configurations, further destabilizes planarity in smaller and medium annulenes. For instance, in [4]annulene, the close proximity of internal hydrogens in a hypothetical planar form generates severe steric crowding, with energy differences between twisted and planar conformers on the order of 3-7 kcal/mol, prompting adoption of a C_2-symmetric twist to alleviate these clashes.[39] Bridged derivatives, such as 1,6-methano[4]annulene, mitigate this repulsion by constraining the geometry, thereby promoting planarity and bond length equalization.[39] The interplay of bond hybridization and resonance energy also critically influences stability, as aromatic annulenes benefit from enhanced delocalization that offsets geometric distortions. In nearly planar aromatic systems like [6]annulene, sp² hybridization facilitates uniform π-orbital overlap, yielding a resonance stabilization energy of approximately 19 kcal/mol and providing a thermodynamic drive toward near-planarity.[48] This delocalization energy, estimated via hydrogenation enthalpies, underscores how Hückel's rule complements structural factors by predicting aromaticity only when planarity is feasible.[48] External factors such as temperature and solvent modulate conformational equilibria, affecting the population of planar versus non-planar forms. In [6]annulene, low-temperature NMR studies reveal a preference for the near-planar aromatic conformer, with dynamic bond shifting barrier of about 3 kcal/mol that allows fluxional behavior influencing spectral properties.[49] Solvent polarity similarly impacts chemical shifts and stability, as polar environments can stabilize charged or polar conformers through solvation effects on π-electron distribution.[50]Synthesis Methods

Approaches for Smaller Annulenes

The synthesis of smaller annulenes (n < 12) presents unique challenges due to ring strain and high reactivity, often leading to low yields from competing polymerization pathways. These compounds, such as [2]annulene (benzene) and [10]annulene (cyclooctatetraene), were initially accessed through multi-step degradative or cycloaddition routes, while derivatives of [4]annulene benefited from later advances in olefin metathesis. A practical method for [10]annulene is the Reppe synthesis, involving nickel-catalyzed tetramerization of acetylene to yield cyclooctatetraene in up to 90% yield. A seminal historical method for [10]annulene involved zinc dust distillation of pseudopelletierine derivatives, developed by Richard Willstätter around 1911. This multi-step process yielded only a small amount of cyclooctatetraene from large quantities of starting material (low overall yield), hampered by extensive side reactions including polymerization of the reactive polyene product. For [2]annulene, the Diels-Alder cycloaddition of 1,3-butadiene with acetylene affords 1,4-cyclohexadiene as the initial adduct, which is subsequently dehydrogenated (e.g., via catalytic or thermal means) to benzene. This approach exemplifies the power of pericyclic reactions for constructing strained six-membered conjugated rings, though practical yields are limited by the volatility of acetylene and potential oligomerization during dehydrogenation. Diels-Alder strategies have also been applied to [10]annulene precursors, where diene-dienophile adducts are formed and then dehydrogenated to the tetraene, offering an alternative to distillation methods with improved control over ring formation but still challenged by low overall efficiency due to strain-induced instability.[51] The synthesis of [4]annulene typically involves partial hydrogenation of pentadehydro[4]annulene precursors obtained via oxidative coupling, though ring-closing metathesis (RCM) using Grubbs' ruthenium catalysts has been applied to acyclic polyenes for bridged derivatives like 1,6-methano[4]annulene, providing moderate yields (40-70%) with E/Z selectivity influenced by strain, followed by adjustments to achieve conjugation. Across these methods, yield and purity issues persist, primarily from polymerization side reactions; the electron-rich conjugated systems readily undergo radical or cationic oligomerization, especially under heating or acidic conditions, necessitating inert atmospheres and stabilizers to isolate pure products. In contrast to larger annulenes, which employ stepwise fragment assembly to avoid strain, smaller systems rely on these direct cyclization techniques.[52]Strategies for Larger Annulenes

The synthesis of larger annulenes (n ≥ 12) requires strategies that address their inherent instability, conformational flexibility, and propensity for decomposition, often involving multi-step constructions to achieve planar, conjugated macrocycles. A foundational method is the oxidative coupling of acyclic polyynes, as developed by Sondheimer for [6]annulene. This approach entails the iterative formation of a hexadehydro[6]annulene precursor through copper-mediated oxidative coupling of terminal diynes, which cyclizes the linear polyyne chain into a macrocycle. Subsequent partial hydrogenation with a Lindlar catalyst reduces the triple bonds to cis double bonds, yielding the all-cis [6]annulene with its characteristic 18π-electron aromatic system. This technique has been instrumental in scaling up to larger rings by controlling the coupling sequence to minimize side reactions like polymerization. Template-directed synthesis has been employed for related macrocycles like porphyrin nanorings to enforce planarity, but for hydrocarbon annulenes, metal coordination is less common; metalloannulenes with embedded metals provide rigidity in some cases. Recent innovations include photocyclization of linear polyenes under mild conditions, typically involving UV irradiation in the presence of iodine or sensitizers, to form extended conjugated systems, though primarily applied to polyarenes rather than simple larger annulenes. Complementing this, 2025 developments in metalloannulene routes leverage coordination chemistry to integrate metals directly into the annulene core, yielding in-plane aromatic [35]annulenes. These syntheses employ stepwise [2+2+2] cycloaddition of organometallic fragments around a central metal, such as osmium, to form planar pentagonal-ring systems with shared metal-carbon bonds, bridging classical annulene chemistry with modern organometallic frameworks for enhanced stability.[53] Purification of larger annulenes demands techniques that mitigate their sensitivity to oxygen, light, and heat, with low-temperature chromatography being a standard protocol. The crude macrocycle is typically separated on cooled alumina or silica columns (e.g., at -20°C using a dry ice-methanol jacket) with non-polar eluents like benzene-methanol mixtures, allowing isolation of the air-sensitive product as red-brown crystals or solutions stable under inert conditions. This method prevents Diels-Alder dimerization or rearrangement, ensuring high purity for subsequent characterization and storage, often in benzene-ether at low temperatures.[54]Properties and Reactivity

Physical Properties

Annulenes, as fully conjugated cyclic hydrocarbons, generally appear as colorless liquids or solids for smaller ring sizes, such as cyclooctatetraene ([10]annulene), which is a clear, colorless liquid at room temperature.[55] Larger aromatic annulenes, however, display coloration due to a reduced HOMO-LUMO energy gap that allows absorption in the visible spectrum; for instance, [6]annulene forms red-brown crystals with a metallic luster.[56] This color arises from the extended π-conjugation in planar aromatic systems, contrasting with the non-aromatic or anti-aromatic smaller annulenes that lack such visible absorption. Solubility profiles of annulenes reflect their nonpolar hydrocarbon nature, rendering them insoluble in water but readily soluble in organic solvents like benzene, ether, and tetrahydrofuran. Solubility often improves with increasing ring size, as larger annulenes experience less angular strain and possess greater hydrophobic surface area, facilitating better dissolution in nonpolar media; [6]annulene, for example, is stably stored in benzene-ether solutions.[56] Thermal properties vary significantly with ring size and aromaticity. Smaller annulenes like [10]annulene boil at approximately 142°C without decomposition, behaving as typical volatile hydrocarbons. In contrast, larger annulenes are solids that typically decompose or sublime prior to melting due to thermal instability of the strained conjugated framework; [13]annulene decomposes at 92–93°C, while [6]annulene sublimes at 120–130°C under reduced pressure (0.01 mmHg) without liquefaction.[57][58] Spectroscopic signatures, particularly UV-Vis absorption, provide insights into conjugation length and aromatic character. Absorption maxima shift to longer wavelengths (bathochromic shift) as ring size increases, reflecting extended delocalization; non-aromatic [10]annulene absorbs around 260 nm in the UV region, whereas aromatic [6]annulene extends into the visible (ca. 400–500 nm), correlating with its observed color and a diamagnetic ring current indicative of aromaticity.[59]Chemical Reactivity

The reactivity of annulenes is profoundly influenced by their aromatic character, as determined by Hückel's rule and structural planarity. Aromatic annulenes, possessing 4n + 2 π electrons in a cyclic, conjugated, planar system, exhibit enhanced stability and preferentially undergo electrophilic substitution reactions that preserve the delocalized π-system, akin to benzene. In contrast, non-aromatic and anti-aromatic annulenes, often due to 4n π electrons or deviations from planarity, behave like typical polyenes and are susceptible to electrophilic addition across their double bonds, which disrupts conjugation without significant energetic penalty. Non-aromatic annulenes such as [10]annulene (cyclooctatetraene) readily undergo electrophilic addition reactions. For instance, treatment with bromine results in the addition product 5,6,7,8-tetrabromocyclooctane, reflecting its tub-shaped, non-planar conformation and lack of aromatic stabilization. This reactivity underscores the preference for addition over substitution in systems without delocalized aromatic electrons.[60] Aromatic annulenes, exemplified by [6]annulene, display substitution reactivity characteristic of aromatic systems. Electrophilic aromatic substitution occurs readily, as demonstrated by nitration to yield nitro[6]annulene and acetylation to form acetyl[6]annulene, with the substituents positioned to maintain the planar, conjugated framework.[61] These reactions proceed via a Wheland intermediate, preserving the 18 π-electron aromaticity, and the products exhibit temperature-dependent NMR spectra indicative of conformational adjustments around the substitution site.[61] Medium-sized annulenes, such as [4]annulene and [5]annulene, often deviate from planarity due to transannular steric interactions, rendering them non-aromatic despite formal adherence to Hückel's rule in some cases. This non-planarity enables them to act as dienes in Diels-Alder cycloadditions; for example, [4]annulene reacts with maleic anhydride to form a bridged adduct, highlighting their polyene-like behavior.[62] Similarly, [5]annulene participates in such [4+2] cycloadditions, further evidencing reduced aromatic stabilization from conformational distortion.[62] Larger annulenes beyond [6] exhibit heightened sensitivity to oxidation, often leading to ring degradation or opening upon air exposure, attributed to their extended conjugated systems and marginal planarity. For instance, attempts to isolate [37]annulene derivatives reveal rapid oxidative polymerization or decomposition in ambient conditions, limiting their stability compared to smaller aromatic analogs.[63] This vulnerability arises from the reactive π-electrons in strained, flexible rings, promoting oxygen addition and subsequent cleavage.[64]Notable Examples

Aromatic Annulenes

[2]Annulene, commonly known as benzene, represents the simplest and most stable aromatic annulene, featuring a planar ring with six conjugated pi electrons that satisfy Hückel's rule for aromaticity (4n + 2, where n = 1). This delocalized electron system imparts exceptional chemical stability, resistance to addition reactions, and characteristic reactivity patterns such as electrophilic substitution, making it a cornerstone of organic chemistry. [4]Annulene, or cyclodeca-1,3,5,7,9-pentaene, possesses 10 π electrons (4n + 2, where n = 2), fulfilling Hückel's rule for aromaticity. However, it is thermodynamically unstable at room temperature due to angle strain in its planar form but exhibits temperature-independent NMR spectra indicative of delocalized electrons when stabilized, such as in derivatives or at low temperatures.[7] [6]Annulene, or cyclooctadeca-1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15,17-nonaene, is a larger cyclic polyene with 18 pi electrons (4n + 2, where n = 4), synthesized in 1959 through a multi-step process involving partial hydrogenation of a dehydro precursor. Its aromatic character is evidenced by diatropic ring currents observed in the 1H NMR spectrum, with outer protons appearing at approximately 9.3 ppm and inner protons at -3.0 ppm, indicating significant shielding within the ring. X-ray crystallographic analysis reveals a nearly planar conformation with alternating single and double bond lengths (short bonds ~1.39 Å, long bonds ~1.42 Å), which average to suggest pi-electron delocalization despite local bond alternation. Cyclotetradecaheptaene, often referred to as [5]annulene, is a hydrocarbon with molecular formula C14H14.[2] It played an important role in the development of criteria for aromaticity, including validation of Hückel's rule.[18] [5]Annulene, or cyclotetradeca-1,3,5,7,9,11,13-heptaene, possesses 14 π electrons (4n+2 with n=3), which theoretically supports aromaticity. First synthesized in 1960 by Franz Sondheimer and Yehiel Gaoni through partial hydrogenation of a dehydro[5]annulene precursor, the compound adopts a saddle-shaped conformation with C_s symmetry, characterized by alternating bond lengths (short ~1.36 Å, long ~1.45 Å) and out-of-plane deviations up to 1.5 Å, as determined by X-ray crystallography. It forms dark-red needle-like crystals.[31] This non-planar arrangement is fluxional at room temperature with rapid conformational interconversions observable via variable-temperature NMR (coalescence at ~ -50°C), resulting in only weak aromatic character due to limited orbital overlap for a sustained ring current.[65][66] Like other larger annulenes, [5]annulene shows heightened reactivity, prone to polymerization under ambient conditions. [37]Annulene, cyclotriaconta-1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15,17,19,21,23,25,27,29-pentadecaene, exemplifies an even larger aromatic system with 30 pi electrons (4n + 2, where n = 7), first synthesized in 1962 via oxidative coupling and partial reduction of a triyne precursor.[67] Although prone to conformational twisting that can lead to paratropic (anti-aromatic-like) behavior in non-planar forms, its planar conformers exhibit diatropic NMR shifts consistent with aromaticity.[40] This compound highlights the challenges in maintaining planarity for larger annulenes while preserving the stabilizing effects of aromatic delocalization.Non-Aromatic and Anti-Aromatic Annulenes

Cyclooctatetraene, also known as [10]annulene, features eight π electrons in a conjugated cyclic system, satisfying Hückel's 4n rule for potential anti-aromaticity in a planar configuration. To circumvent this destabilizing effect, the molecule adopts a non-planar tub-shaped conformation with alternating single and double bonds and a D2d symmetry, as confirmed by electron diffraction studies revealing C-C bond lengths of approximately 1.34 Å for double bonds and 1.46 Å for single bonds, along with an average angle of deviation from planarity around 30 degrees. This distortion disrupts the cyclic conjugation, rendering the compound non-aromatic rather than anti-aromatic, and contributes to its relative stability compared to hypothetical planar counterparts, though it remains reactive toward addition reactions such as Diels-Alder cycloadditions.[39] [20]Annulene, or cyclododeca-1,3,5,7,9,11-hexaene, contains 12 π electrons (4n with n=3), which would confer anti-aromatic character in a planar form according to Hückel's rule. Synthesized in 1965 via oxidative coupling of a suitable acyclic precursor, the molecule avoids planarity by assuming a helical twisted conformation with approximate C2 symmetry, featuring bond alternation and trans double bonds that relieve strain and interrupt full conjugation. This non-planar geometry results in non-aromatic behavior, evidenced by its 1H NMR spectrum showing olefinic protons at δ 5.8-6.5 ppm without the paratropic shifts typical of anti-aromatic systems.[39] However, [20]annulene exhibits significant instability, rapidly polymerizing or undergoing addition reactions above -20°C, which limits its isolation to low temperatures and underscores the energetic cost of its distorted structure.References

- [14]annulene is an aromatic annulene. ChEBI Contents Title and Summary 5 Chemical Vendors 9 Information Sources 1 Structures 1.1 2D Structure

- Etymology. Latin annulus "ring" + -ene ; First Known Use. 1962, in the meaning defined above ; Time Traveler. The first known use of annulene was in 1962. See ...

- Annulene is the common name for cyclic conjugated hydrocarbons. For example, [6]annulene - benzene, [8]annulene - cyclooctatetraene, etc.Missing: term | Show results with:term

- Thiele, who discovered the unusual sta- bility of the cyclopentadienyl anion, applied his ingenious “partial valence” concept (1899) broadly to rationalize the ...

- Definition: Annulenes are mancude monocyclic hydrocarbons without side chains.

- Jan 2, 2015 · In January 1865, August Kekulé published his theory of the structure of benzene, which he later reported had come to him in a daydream about a snake biting its ...

- 2 The name [n]annulene is used in preferred IUPAC names as a parent component in fusion nomenclature (see P-25.3.2.1.1) and may be used in general ...

- Jul 3, 2023 · In 1865, German chemist Friedrich August Kekulé published a paper in which he described benzene as consisting of a ring of six carbon atoms ...

- [14]Annulene: Cis/Trans Isomerization via Two-Twist and Nondegenerate Planar Bond Shifting and Möbius Conformational Minima. Click to copy article link ...

![Cyclobutadiene ([4]annulene)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/Cyclobutadien.svg/120px-Cyclobutadien.svg.png)

![Benzene ([6]annulene)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Benzol.svg/120px-Benzol.svg.png)

![Cyclooctatetraene ([8]annulene)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/ba/Cyclooctatetraen.svg/120px-Cyclooctatetraen.svg.png)

![Cyclodecapentaene ([10]annulene)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/98/All-cis-cyclodecapentaene.svg/120px-All-cis-cyclodecapentaene.svg.png)

![Cyclododecahexaene ([12]annulene)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Cyclododecahexaene.svg/120px-Cyclododecahexaene.svg.png)

![Cyclotetradecaheptaene ([14]annulene)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/%2814%29Annulene.svg/88px-%2814%29Annulene.svg.png)

![Cyclooctadecanonaene ([18]annulene)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/33/%2818%29Annulene.svg/120px-%2818%29Annulene.svg.png)

![Cyclodocosahendecaene ([22]annulene)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Cyclodocosahendecaene.svg/120px-Cyclodocosahendecaene.svg.png)