Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Appearance Manager

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) |

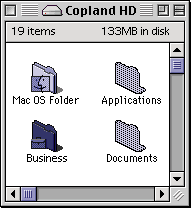

The Appearance Manager is a component of Mac OS 8 and Mac OS 9 that controls the overall look of the Macintosh graphical user interface widgets and supports several themes.[1] It was originally developed for Apple's ill-fated Copland project, but with the cancellation of this project the system was moved into newer versions of the Mac OS. The Appearance Manager is also available free as part of a downloadable SDK for System 7.[2]

The Appearance Manager is implemented as an abstraction layer between the Control Manager and QuickDraw. Previously, controls made direct QuickDraw calls to draw user interface elements such as buttons, scrollbars, window title bars, etc. With the Appearance Manager, these elements are abstracted into a series of APIs that draw the item as a distinct entity on behalf of the client code, thus relieving the Control Manager of the task. This extra level of indirection allows the system to support the concept of switchable "themes", since client code simply requests the image of an interface element (a button or scroll bar, for example) and draws its appearance. Kaleidoscope, a 3rd party application, was the first to utilize this functionality with via "scheme" files, followed by an updated Appearance Control Panel in Mac OS 8.5, which acted similarly via "theme" files. Schemes and themes are similar in concept, but they are not internally compatible.

An updated and more powerful version of the Appearance Manager was used for Carbon applications in Mac OS X even after Apple made the transition to Aqua. The Extras.rsrc file is an updated version of an Appearance Theme that is compatible with the newer Appearance Manager. As of Mac OS X version 10.3, 'layo' data is no longer used, even for Carbon applications, so the continued existence of the Appearance Manager can no longer be confirmed.

Appearance themes

[edit]

The default look and feel of the Appearance Manager in Mac OS 8 and 9 is Platinum design language, which was intended to be the primary GUI for Copland. Platinum retains many of the shapes and positions of elements from System 7 and earlier, like window control widgets and buttons and while Charcoal is the default system font, Chicago was available via a menu option. However, various shades of grey are used extensively throughout the interface, as opposed to previous interfaces which are mostly monochrome black and white. Apple Platinum is not a theme, however, as it is actually embedded into the Appearance Manager. The Appearance Control Panel has the ability to attach a theme to the Appearance Manager. There is an Apple Platinum file in the themes folder in the System Folder which acts as a stub, but no functional theme elements are embedded into it. Customizable palettes ('clut' resources) are used for progress bars, scroll thumbs, slider tabs and menu selections in Apple Platinum and this unique option is not available to real themes. The Appearance Control Panel uses the type code 'pltn' to identify if a file should act like a palette modification stub to Apple Platinum and the type code 'thme' to identify if a file should act like an Appearance Theme. An important distinction is that the Appearance Control Panel implements themes into the Appearance Manager. Kaleidoscope is third-party software that implements schemes into the Appearance Manager. Kaleidoscope is not a substitute for the Appearance Manager; it is a substitute for the Appearance Control Panel.

Apple widely demonstrated two Appearance Themes which override Apple Platinum, Hi-Tech and Gizmo. Hi-Tech is based on a shades-of-black color scheme that made the interface look like a contemporary piece of audio-visual equipment. Gizmo is a period-appropriate Memphis-style interface, using many bold colors, patterns, and "wiggly" interface elements. Both changed every single element of the overall GUI, leaving no trace of Apple Platinum. A third theme, Drawing Board, was later introduced, developed at Apple Japan. This theme uses elements that make the interface look like it has been drawn in pencil on a drafting board, including small "pencil marks" around the windows, a barely visible graph paper grid on the desktop, and "squarish" elements with low contrast. Although themes are supported in all released versions of Mac OS 8.5 through 9.2.2, the three aforementioned themes were only present in pre-release versions of Mac OS 8.5 and were removed without explanation in the final release.[1]

One retrospective review by a long-time Mac user described the themes as being a mistake and waste of engineering resources, saying the "Hi-Tech" theme "looked like a typical dark over-decorated techno skin that became popular for Linux desktops" and that "Gizmo" looked "awful...the Finder in a clown suit".[3]

Typography

[edit]By default, a font called Charcoal is used to replace the similar Chicago typeface that was used in earlier versions of the Mac OS. A number of additional system fonts are also provided, including Capitals, Gadget, Sand, Techno, and Textile. In order to be a system font, glyphs specific to the Mac operating system need to be provided, such as the Command key symbol (⌘). System fonts are normally displayed at 12 points.

Later versions of the Appearance Manager also apply anti-aliasing to type displayed on the screen above a certain size, by default 12 points. This improves the overall look of the text by reducing the perception of rasterization artifacts. Anti-aliasing is adjustable in the Appearance Control Panel.

Shareware products

[edit]Shareware products exist that provided some features of the Appearance Manager before they were offered directly in the Appearance Control Panel. Church Windows and Décor provide desktop picture functionality. WindowShade, which had been purchased by Apple and bundled with System 7.5,[4] provides collapse functionality. When windows collapse, they "roll up", leaving only the title bar.

Kaleidoscope

[edit]

Kaleidoscope, written by Arlo Rose and Greg Landweber, applied "schemes" to the GUI before Apple released an update to the Appearance Control Panel with Mac OS 8.5 which provides similar functionality using "themes". Whereas only a handful of themes were ever developed, thousands of Kaleidoscope schemes were developed.

When theme support in the Appearance Control Panel was first announced, the team responsible for it demonstrated an automatic tool specifically designed to convert the tens of thousands of existing Kaleidoscope scheme files into Appearance Manager-compatible theme files. This tool was not released to the public;[5] however, a similar tool has been developed.[6]

Kaleidoscope remained the primary theming platform, even after the Appearance Control Panel offered theming capabilities in Mac OS 8.5. Steve Jobs returned to Apple just before the release of Mac OS 8.5, and he decided to officially drop support for themes because he wanted to preserve a consistent user interface. Because of this, Apple released little documentation for the theme format, withheld their own beta-released themes, and even issued a cease and desist notice to the authors of a third-party theme editor on grounds that it was intended to allow users to create themes that imitate the Aqua interface in Mac OS X.[7] At the same time, the format of Kaleidoscope schemes continued to evolve. As a result, Kaleidoscope schemes proliferated while Appearance themes never really took off. Kaleidoscope was only rendered obsolete with the transition to Mac OS X, with which Kaleidoscope is not compatible.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Brickness, K.J. (2001). Carbon Programming. SAMS. p. 220. ISBN 9780672322679.

- ^ "FTP link". ftp.apple.com (FTP).[dead ftp link] (To view documents see Help:FTP)

- ^ "Retro Mac Computing: the long view". The Long View. Basal Gangster. February 26, 2011. Archived from the original on April 1, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Gruber, John (January 21, 2009). "Three things OS X could learn from the Classic Mac OS". Macworld. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ Aqua, schemes and themes - Apple demonstrates Kaleidoscope-scheme-to-8.5-theme converter

- ^ Boldt, Ben. "Scheme to Theme Converter". www.d.umn.edu. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018.

- ^ Fidéle, Dominique (April 17, 2001). "Apple lawyers target Mac Themes Project". Macworld UK. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014.

Appearance Manager

View on GrokipediaOverview and History

Introduction

The Appearance Manager is a software component of the classic Mac OS operating system, introduced in Mac OS 8.0, that manages the visual aspects of user interface elements such as colors, patterns, and controls.[1] It serves as a centralized subsystem to define and apply consistent graphical appearances across the system's windows, menus, dialogs, and other widgets, ensuring uniformity without developers needing to embed specific visual code in their applications.[4] The primary purpose of the Appearance Manager is to enable customizable and themeable interfaces that adapt to user preferences, promoting a cohesive look throughout the operating system and third-party software.[1] By abstracting visual definitions into system-level functions, it allows applications to query and use dynamic appearances, reducing redundancy and easing maintenance for UI updates. This approach supports extensibility, such as customization options via the Appearance control panel, with full multi-theme switching added in Mac OS 8.5.[4] Key benefits include enhanced aesthetics through support for the default platinum-style interface, which introduces three-dimensional effects like beveled edges and anti-aliased elements for a more modern appearance compared to prior Mac OS versions.[1] The manager was initially released on July 26, 1997, alongside Mac OS 8.0, marking a significant evolution in Macintosh user interface design.[5]Development and Release

The Appearance Manager emerged as a response to increasing user demands for customizable user interfaces in the Macintosh operating system following the release of System 7 in 1991, which had introduced color but limited personalization options. This push was further influenced by the aesthetic innovations of Windows 95, released in 1995, prompting Apple to modernize the Mac's visual design with more dynamic and three-dimensional elements to remain competitive.[6] Development of the Appearance Manager was integrated into broader initiatives by Apple's Human Interface Group and the Interface Builder team during the mid-1990s, focusing on standardizing and enhancing graphical user interface components for consistency across applications. These efforts aimed to unify the look of system widgets, menus, and windows while enabling theme-based customization. Prior to its full integration in Mac OS 8, versions 1.0 through 1.0.3 of the Appearance Manager were released as extensions compatible with System 7.1 to 7.6.1, enabling partial appearance support on earlier systems.[2][7] The technology debuted with the release of Mac OS 8.0 on July 26, 1997, introducing the foundational APIs for appearance control and the initial Platinum theme. Enhancements followed in Mac OS 8.1 on January 19, 1998, which introduced an option to disable the Platinum theme, added support for the HFS Plus file system, and included minor updates to the Appearance Manager (version 1.0.1). Further refinements to the Appearance Manager, including version 1.1 updates for improved control rendering, continued through subsequent releases up to Mac OS 9.2.2 in December 2001.[6][8][9][7] Beta testing for Mac OS 8, including early builds of the Appearance Manager, was conducted via Apple's Technology Seed program for developers from 1996 through mid-1997, allowing feedback on UI prototypes before the final launch. Initial reception was largely positive, with users and reviewers praising the modernized, customizable interface that brought the Mac in line with contemporary standards, though it faced criticism for its hardware demands, requiring at least a 68040 processor and 8 MB of RAM (ideally 16 MB or more for smooth performance).[10][11][12]Core Components

The Appearance Manager provides developers with a set of APIs defined in the Appearance.h header file, enabling applications to create theme-compliant user interfaces on Mac OS 8 and later.[13] Key functions includeRegisterAppearanceClient and UnregisterAppearanceClient for registering applications as clients to receive theme change notifications, as well as IsAppearanceClient to verify registration status.[14] Theme management functions such as SetThemeBackground, SetThemeWindowBackground, SetThemePen, and SetThemeTextColor allow developers to apply theme-specific colors and patterns to drawing operations.[13] For menus, functions like GetThemeMenuBackgroundRegion and DrawThemeMenuBackground handle themed rendering based on menu types, with constants such as kThemeMenuTypePullDown or kThemeMenuTypePopUp specifying the context.[15]

Key subsystems encompass drawing routines and resource management mechanisms that form the architectural foundation for themed UI elements. Drawing routines include primitives like DrawThemeWindowFrame, DrawThemeEditTextFrame, DrawThemeListBoxFrame, and DrawThemeFocusRect, which render controls in the active theme's style while supporting states such as kThemeStateActive or kThemeStateInactive.[13] These routines replace or augment legacy definition procedures (e.g., WDEF for windows, CDEF for controls) with Appearance-compliant equivalents, using resource IDs like 63 for menu bars. Resource management involves data-driven themes stored in files, loaded dynamically to support switching without restarting the system; mappers translate pre-Appearance resources to themed versions, ensuring consistent appearance across UI components.[16]

The Appearance Manager integrates seamlessly with QuickDraw, the legacy graphics system, by extending it for themed rendering while preserving backward compatibility. It provides themed equivalents to QuickDraw calls, such as using DrawThemeEditTextFrame instead of FrameRect for frames, with conditional branching to fall back to classic QuickDraw functions if the Appearance Manager is unavailable.[16] This mapping—e.g., redirecting WDEF ID 0 to ID 64—allows legacy applications to render with modern themes automatically, without requiring code changes, by intercepting and enhancing QuickDraw operations at the system level.[13] The IsThemeInColor function further ensures themed drawing only on color-capable displays, adapting to monochrome environments if needed.[13]

System requirements for the Appearance Manager align with Mac OS 8 specifications, mandating a minimum of 8 MB RAM and support for 256-color (8-bit) displays or higher via Color QuickDraw to enable full themed rendering.[11] Higher resolutions and deeper color depths enhance performance, but the system gracefully degrades on lower-spec hardware by using fallback drawing modes.[16]

User Interface Customization

Color Management

The Appearance Manager supports various color models to ensure consistent rendering of user interface elements across different display devices. It integrates with the ColorSync system, which provides capabilities for RGB and CMYK color spaces, as well as device-independent color spaces such as CIE XYZ, Lab*, and Luv*. This integration allows for accurate color matching and conversion, preventing discrepancies in UI appearance when transitioning between input, display, and output devices.[17] The default color palette in the Appearance Manager is based on the Platinum scheme, characterized by neutral grays for backgrounds and structural elements, subtle blues for accents, and customizable highlights to enhance interactivity. Users can edit these palettes through the system's Color Picker, accessible via the Appearance control panel, enabling selection or creation of accent and highlight colors to personalize the interface while maintaining thematic consistency.[18] For dynamic theming, the Appearance Manager offers API functions such asSetThemeBackground, SetThemePen, and SetThemeTextColor to apply theme-specific colors to UI components like menus, buttons, and highlights in real time. These calls specify parameters for color depth (e.g., 8-bit or 24-bit) and device type, ensuring adaptive rendering that aligns with the active theme without requiring full redraws.[2]

Early versions of the Appearance Manager, introduced in Mac OS 8, were constrained by 8-bit color depth limitations inherited from the Palette Manager, restricting UI elements to a limited set of 256 colors. These constraints were resolved in Mac OS 8.5 with the adoption of 32-bit QuickDraw, providing full 24-bit true color support and enabling richer, gradient-based appearances for themes.[2]

Theme System

The Theme System in the Appearance Manager establishes a unified framework for defining and applying visual styles to Macintosh interface elements, ensuring consistency across windows, menus, controls, and other UI components. Theme files reside in the System Folder/Appearance/Themes folder and consist of resource-based structures that include icons (via resources like 'ics#' and 'ics8'), textures and patterns (such as 'ppat' or pixel map resources), and animation definitions through procedural drawing calls coordinated by the Appearance extension. These resources enable the system to render theme-specific appearances without requiring developers to hardcode visual details in applications.[4][13] Introduced with Mac OS 8.5 in October 1998, the system shipped with the Platinum theme as the default, featuring a three-dimensional metallic design. An option to disable the Platinum appearance reverted the interface to a classic, pre-Mac OS 8 look. Gizmo and Hi-Tech were developed to offer users variety in interface aesthetics while maintaining human interface guidelines for usability, but originated in beta versions and were not included in the final release.[4][19] Theme switching occurs via the Appearance control panel, where users select from available themes in a pop-up menu, view real-time previews of changes to interface elements, and apply the selection system-wide with immediate effect. The process leverages Apple events for notification, allowing applications to refresh their content rectangles and adapt without restarting; caching mechanisms store theme primitives in memory for rapid redrawing and reduced overhead during transitions.[4][13] Customization depth allows users to modify specific theme elements beyond whole-theme selection. Users could modify accent and highlight colors, select system fonts, and toggle options like window shading and sound effects. These edits are performed within the control panel's advanced options, integrating with color schemes while preserving theme integrity through resource overrides.[4]Window and Control Appearance

The Appearance Manager renders windows in themed mode with distinctive 3D features, including beveled edges along the frame to create depth and a sense of layering. Title bars incorporate subtle shading—often described as gradients in the platinum theme—to differentiate active and inactive states, with active windows featuring darker outlines and highlighted controls such as close, zoom, and collapse boxes. Resize handles appear as integrated elements in the lower-right corner of the window, styled to match the current theme for seamless visual consistency.[4] Interactive controls are drawn using theme-compliant primitives, ensuring uniform appearance across applications. Push buttons take the form of rounded rectangles measuring 20 pixels in height, supporting three states (normal, pressed, and disabled) with beveled outlines for tactile feedback. Bevel buttons offer variable bevel depths (2-4 pixels) and up to seven states, allowing them to emulate push buttons, radio buttons, or checkboxes while incorporating etched shadows for dimensionality. Sliders, available in horizontal or vertical orientations, include a movable indicator and optional tick marks, providing live feedback during dragging to indicate value changes. Pop-up menus feature a characteristic double-arrow icon on the button, with the menu itself displaying themed icons and subtle drop shadows upon activation to enhance readability and hierarchy.[4][1] Subtle animation effects, such as smooth window collapse and expansion transitions, are supported through Appearance Manager routines accessible via the Carbon framework, allowing developers to enable dynamic behaviors like menu appearances without abrupt changes. Theme switching directly influences control rendering by reapplying the selected appearance's colors, shapes, and effects to all elements in real time.[20][4]Typography and Text Handling

Font Integration

The Appearance Manager integrates with the Macintosh font system to manage text in user interface elements, supporting TrueType and PostScript Type 1 fonts using QuickDraw for scalable typography and rendering. This integration allows the system to handle outline-based fonts efficiently, enabling consistent appearance across themed elements without requiring direct font management in applications.[18] In early versions of Mac OS 8, the default UI fonts were Charcoal, a sans-serif TrueType font designed for general interface text such as menus and dialogs, and Chicago, a bitmap font retained for alerts to maintain readability in fixed-size displays.[18] These choices ensured a clean, modern look while preserving compatibility with legacy display constraints, with Charcoal serving as the primary system font to replace Chicago's role from prior OS versions.[18] The Appearance Manager exposes APIs for font handling, including the functionGetThemeFont, which retrieves the appropriate themed font ID, name, size, and style for specific UI contexts like system fonts or labels, allowing developers to query and apply consistent typography programmatically, often specifying the script system such as smSystemScript.[21][22] This enables applications to adapt to user-selected themes dynamically without hardcoding font details.

For enhanced scalability on higher-resolution monitors, Mac OS 8.5 introduced built-in font anti-aliasing via the Appearance control panel, applying smoothing to TrueType outlines for reduced jagged edges and improved legibility at various sizes.[23] Users could toggle this feature to balance clarity and performance, marking a key advancement in text display quality over prior pixel-based rendering.[24]

Text Rendering Features

The Appearance Manager extends QuickDraw's text rendering capabilities by providing specialized functions for drawing themed UI text using outline fonts, ensuring consistent appearance across interface elements. These extensions leverage the existing QuickDraw text procedures, such as DrawString and DrawText, but integrate theme-specific attributes like font selection and style application to support scalable outline fonts from TrueType and Adobe Type 1 formats. For instance, the DrawThemeTextBox function renders text with proper scaling and positioning for controls and dialogs, building on QuickDraw's baseline-aligned drawing model.[20][25] Key to these extensions is support for hinting and kerning in outline fonts, handled by the font scalers during rasterization. Hinting instructions within TrueType or Type 1 fonts adjust glyph outlines to align with pixel grids, improving legibility at small sizes on low-resolution displays, while kerning pairs from font metrics adjust spacing between specific character combinations for better typographic quality. In the context of Appearance Manager, these features are applied when rendering themed text in QuickDraw ports, particularly for UI elements where precise alignment is critical.[25] Themed text styles in the Appearance Manager include predefined variants such as bold, italic, and shadowed effects, tailored for interface components like dialog boxes, menus, and buttons. Developers access these via constants like kThemeSystemFont for the primary UI font or kThemeSmallSystemFont for compact elements, with style modifiers (e.g., bold or italic) applied through UseThemeFont to set the graphics port's text attributes. Shadowed variants, often used for emphasis in alerts or labels, combine outline rendering with offset duplicates in theme colors, enhancing depth without relying on legacy bitmap effects. These styles ensure uniformity across themes like Platinum, adapting to user-selected appearances.[20] Compared to System 7, the Appearance Manager introduces notable enhancements, including partial anti-aliased text support in QuickDraw for smoother outline rendering at the standard 72 dpi resolution. This anti-aliasing, enabled via the Appearance control panel in Mac OS 8.5 and later, blends glyph edges to simulate higher effective resolution (up to 2x, akin to 144 dpi modes), reducing jaggedness in scalable fonts without requiring hardware changes. While implementation was initially limited to specific QuickDraw calls and font scalers like TrueType 3, it marked a shift toward resolution-independent text display in classic Mac OS.[26][20]Compatibility with Legacy Fonts

The Appearance Manager preserved compatibility with legacy bitmap fonts, known as NFNT resources, by integrating with QuickDraw's text rendering system, which defined these fonts as fixed-size collections of character images for specific typefaces and styles, such as 12-point Geneva italic. For unthemed applications that did not adopt the new theme system, the manager fell back to the Platinum appearance, defaulting to classic bitmap fonts like Chicago for the large system font and Geneva for the small system font to maintain visual consistency with pre-Mac OS 8 interfaces. On higher-resolution displays, QuickDraw scaled these bitmap fonts using pixel-doubling—replicating pixels to enlarge the image without interpolation—to avoid jagged artifacts while preserving the original pixelated aesthetic.[25][27] To address font format transitions, support for Adobe Type 1 fonts was available via the Adobe Type Manager extension alongside native TrueType, encouraging conversion from legacy PostScript formats to scalable TrueType for better performance under the Appearance Manager's theming. However, deep bitmap fonts (color NFNTs) remained unsupported, limiting advanced features like multicolored glyphs in legacy setups.[26][25] By Mac OS 9, bitmap fonts remained supported for compatibility in QuickDraw operations.[28]Third-Party Extensions

Kaleidoscope

Kaleidoscope is a shareware control panel developed by Arlo Rose and Greg Landweber that enabled extensive customization of the Macintosh user interface on System 7 through Mac OS 9. Initially released in 1996 as version 1.0.1, it predated Apple's official Appearance Manager but was quickly adapted to leverage its capabilities upon the release of Mac OS 8 in 1997.[29][30] The software operated by patching the system's drawing routines to apply user-selected "schemes," which were theme files defining colors, patterns, and shapes for interface elements such as windows, menus, scrollbars, and desktop textures. It supported texture mapping for desktops and provided granular control over hidden or subtle UI components, including proportional scrollbars, proxy icons, and custom sounds for actions like window shading. Over 4,000 user-submitted schemes were available through community archives, allowing users to create and share personalized looks ranging from metallic finishes to organic patterns.[31][32][19] Version 2.0, released in 1998, introduced full integration with the Appearance Manager, enabling seamless application across Appearance-aware software and adding support for 32-bit icons and enhanced scheme formats for greater flexibility in customization. This update included previews of schemes mimicking emerging designs, such as early "Aqua"-inspired themes with translucent and liquid-like elements, which anticipated Apple's later interface direction. Kaleidoscope's architecture allowed third-party developers to contribute schemes via a plug-in system, fostering a vibrant ecosystem of over a thousand community creations by the late 1990s.[33][19][34] Kaleidoscope achieved widespread popularity as the leading tool for Mac UI theming, with its schemes archive receiving tens of thousands of downloads during beta phases. Its influence extended to Apple's design team, as Apple developed an internal "scheme to theme" converter to import Kaleidoscope files into official themes, and elements of its user-driven aesthetics informed the Aqua interface in Mac OS X. Development ceased with version 2.3.1 in 2001, following the shift to OS X, which imposed restrictions on deep system patching and rendered the tool obsolete.[35][33][36][37]Other Shareware and Commercial Products

Beyond Kaleidoscope, several shareware and commercial products extended the capabilities of the Appearance Manager by providing tools for theme management, conflict resolution, and advanced customization during the late 1990s. Conflict Catcher, released in version 4.1 in 1997 (with updates extending into 1998), offered theme conflict resolution features, allowing users to group and disable conflicting extensions related to Appearance Manager themes to prevent system crashes or visual inconsistencies during startup.[38] These products were primarily distributed through specialized Mac software archives like MacSoft and Info-Mac (now preserved in the Macintosh Repository), where downloads peaked between 1998 and 2001 amid the popularity of Mac OS 8.5 and 9.0 updates that enhanced theme support.[39] A distinctive feature of many such tools was their ability to introduce 3D effects, such as beveled controls and shadowed menus, or web-inspired themes with metallic gradients and transparency simulations that exceeded the native Appearance Manager's platinum style limitations.[1]Integration Challenges

Integrating third-party tools with the Appearance Manager presented several technical hurdles due to the evolving nature of its API and documentation. Full programming documentation for the Appearance Manager was not comprehensively available until April 1999, coinciding with the release of version 1.1 and Mac OS 9, leaving earlier developers with incomplete resources that complicated theme implementation.[40] Prior to this, partial SDK releases from 1997 and 1998 provided basic access but lacked detailed guidance for advanced customization, often requiring developers to navigate undocumented behaviors.[41] Compatibility between the Appearance Manager and legacy applications posed additional challenges, particularly across PowerPC and 68k architectures. The API supported Mac OS versions from 7.1 to 8.0 on both 68k (68020 and later) and PowerPC processors, provided Color QuickDraw was present, but custom controls and nonstandard definition functions (CDEFs/WDEFs) frequently failed to adapt to themes, leading to inconsistent rendering.[41] Third-party extensions addressed these issues by employing wrapper libraries to bridge architectural differences and ensure seamless operation with mixed-application environments.[41] User pitfalls arose from the complexity of theme customization, where overly elaborate schemes could degrade system performance through excessive resource demands. Apple's Human Interface Guidelines, updated through the late 1990s, emphasized using standard Toolbox controls and the system's color palette to maintain consistency and avoid such slowdowns, recommending developers test themes across hardware configurations for stability.[4] These guidelines, formalized in documents like the 1997 Mac OS 8 HIG, promoted safe theming practices to prevent interface disruptions.[4] Developer support remained fragmented, with Apple's SDK distributions offering core APIs but limited tools for extension development, such as no native ResEdit templates for new controls—necessitating third-party utilities like Resorcerer or Constructor.[41] For advanced features beyond documented calls, developers often relied on reverse-engineering system behaviors, a practice that enabled innovations in products like Kaleidoscope but risked instability without official endorsement.[41] Frameworks like PowerPlant in CodeWarrior Pro 2 provided partial integration support, though broader adoption varied.[41]Legacy and Transition

Use in Mac OS 9

In Mac OS 9.0, released in 1999, the Appearance Manager received enhancements that integrated it with the operating system's new multi-user environment, enabling each user to personalize interface themes, colors, and sounds independently through the Multiple Users control panel. This per-user customization extended to the Appearance control panel, where settings like themes and highlight colors could be tailored without affecting other accounts, supporting Normal, Limited, and Panels user types. Additionally, Mac OS 9 introduced Carbon support via the CarbonLib library, improving compatibility for applications that leveraged Appearance Manager APIs while preparing for future transitions to Mac OS X.[43][44] The Appearance Manager served as the default interface manager across all versions of Mac OS 9, from 9.0 through the final release of 9.2.2 in 2001, unifying the look of system elements such as windows, menus, and controls under the Platinum theme or user-selected alternatives. Its widespread use facilitated consistent theming for both native and Carbonized applications, with users able to switch among available themes via the control panel to achieve varied visual styles. This standardization contributed to a cohesive user experience, as developers increasingly adopted Appearance Manager routines for cross-application consistency.[44][43] Subsequent updates in Mac OS 9 addressed reliability issues, including a fix for a large memory leak in the Appearance control panel that could occur during prolonged use. These refinements ensured stable performance for theme rendering and customization, particularly in multi-user setups and with extended sessions. While Mac OS 9 marked the peak of the Appearance Manager's active development in the classic Mac OS era, its features laid groundwork for partial compatibility in the subsequent macOS Classic environment.[44] Mac OS 9 also incorporated Sherlock 2, an updated search tool that relied on the Appearance Manager for its interface elements, allowing seamless integration of themed visuals in file and internet searches introduced in 1999.[44]Replacement in macOS

The Appearance Manager, originally designed for classic Mac OS, was ported to the Carbon framework for compatibility in Mac OS X but was largely superseded starting with Mac OS X 10.0 (released March 24, 2001), where the Aqua graphical user interface introduced new theming and control rendering mechanisms that rendered much of the original API obsolete for native development. Replacement in macOS With the launch of Mac OS X 10.0 in 2001, the Appearance Manager was effectively phased out for new development in favor of the Aqua UI, which integrated themed controls directly into the system's rendering pipeline using the HITheme API within the Human Interface Toolbox.[45] The HITheme API, based on Quartz 2D, provided the means to draw Aqua-compliant interface elements, addressing the limitations of the QuickDraw-dependent Appearance Manager and enabling smoother integration with Mac OS X's vector-based graphics system.[46] In the Cocoa framework, theming capabilities evolved further with the introduction of NSAppearance in Mac OS X 10.9 (2013), allowing developers to define custom appearances for UI elements that adapt to system themes like light and dark modes.[47] For visual effects, Core Animation—debuted in Mac OS X 10.5 (2007)—succeeded the Appearance Manager's basic animation support by leveraging hardware acceleration for layered, composited graphics, enhancing consistency across Apple devices. Backward compatibility for Carbon-based applications permitted continued use of the Appearance Manager until Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard (2009), after which most functions were unavailable in 64-bit applications, with emulation provided for legacy 32-bit code to maintain functionality without full support.[45] Apple's shift away from the Appearance Manager was driven by the need for hardware-accelerated graphics rendering via Quartz and later Core Animation frameworks, ensuring a unified, performant UI experience optimized for modern hardware and multi-device ecosystems.[46]Cultural Impact

The Appearance Manager significantly influenced Mac user culture by encouraging a modding and customization community during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Enthusiasts shared and developed third-party themes through online forums and repositories, such as MacRumors and the Macintosh Repository, where collections of dozens of custom appearances—ranging from beta-exclusive designs to user-created variants—were archived and discussed.[48][39] This activity fostered a sense of creative ownership over the interface, with users experimenting with color schemes, icons, and widgets to personalize their systems, a practice echoed in nostalgic accounts from vintage computing communities.[49] Its design legacy extended to broader personalization trends in Apple's ecosystem, introducing switchable interface themes that emphasized user control over aesthetics, a concept later reflected in macOS features like the 2018 introduction of dark mode and customizable accent colors in subsequent updates. The official Platinum theme was the primary option for toggling, though unreleased beta themes like Hi-Tech and Gizmo inspired community efforts to recreate similar customizations.[24] While celebrated for revitalizing the aging classic Mac interface and delaying the need for a full OS overhaul, the Appearance Manager faced criticism from some quarters for prioritizing visual tweaks over deeper architectural improvements, viewing themes as superficial amid growing demands for multitasking and networking enhancements.[50] Contemporary archival efforts ensure its cultural artifacts endure, with emulators like SheepShaver enabling the execution of Mac OS 9 environments complete with original theme files, allowing modern users to experience and preserve these customizations on contemporary hardware. Community-driven sites continue to host and distribute theme packs, maintaining accessibility for retro computing enthusiasts.[51][39]References

- ftp://devworld.apple.com/MacOS8/