Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Glyph.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Glyph

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Glyph

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

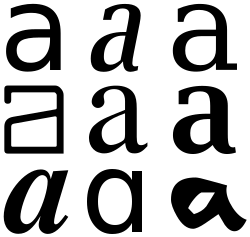

A glyph is a graphical symbol or mark that conveys meaning, often representing a character, sound, word, or concept in writing systems, typography, or visual arts.[1][2] In its broadest sense, the term originates from ancient practices such as Egyptian hieroglyphs or Mayan script, where glyphs served as pictorial or carved symbols incised into surfaces to encode language or ideas.[3][1] Architecturally, a glyph can also refer to an ornamental vertical groove, particularly in Doric friezes of classical Greek design.[1] In modern contexts, especially digital typography and computing, a glyph denotes the specific visual form or design of a character within a font, distinguishing it from the abstract character it represents—for instance, the varying shapes of the lowercase "a" across different typefaces.[4][5] This evolution underscores the glyph's enduring role as a fundamental unit bridging human expression, aesthetics, and technology.[6]