Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

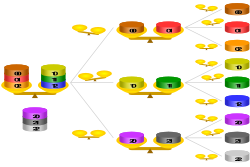

Balance puzzle

View on WikipediaA balance puzzle or weighing puzzle is a logic puzzle about balancing items—often coins—to determine which one has different weight than the rest, by using balance scales a limited number of times.

The solution to the most common puzzle variants is summarized in the following table:[1]

| Known | Goal | Maximum coins for n weighings | Number of weighings for c coins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whether target coin is lighter or heavier than others | Identify coin | ||

| Target coin is different from others | Identify coin | ||

| Target coin is different from others, or all coins are the same | Identify if unique coin exists, and whether it is lighter or heavier |

For example, in detecting a dissimilar coin in three weighings (), the maximum number of coins that can be analyzed is . Note that with weighings and coins, it is not always possible to determine the nature of the last coin (whether it is heavier or lighter than the rest), but only that the other coins are all the same, implying that the last coin is the dissimilar coin. In general, with weighings, one can always determine the identity and nature of a single dissimilar coin if there are or fewer coins. In the case of three weighings, it is possible to find and describe a single dissimilar coin among a collection of coins.

This twelve-coin version of the problem appeared in print as early as 1945[2][3] and Guy and Nowakowski explain it "was popular on both sides of the Atlantic during WW2; it was even suggested that it be dropped over Germany in an attempt to sabotage their war effort".[3]

Nine-coin problem

[edit]

A well-known example has up to nine items, say coins (or balls), that are identical in weight except one, which is lighter than the others—a counterfeit (an oddball). The difference is perceptible only by weighing them on scale—but only the coins themselves can be weighed. How can one isolate the counterfeit coin with only two weighings?

Solution

[edit]To find a solution, we first consider the maximum number of items from which one can find the lighter one in just one weighing. The maximum number possible is three. To find the lighter one, we can compare any two coins, leaving the third out. If the two coins weigh the same, then the lighter coin must be one of those not on the balance. Otherwise, it is the one indicated as lighter by the balance.

Now, imagine the nine coins in three stacks of three coins each. In one move we can find which of the three stacks is lighter (i.e. the one containing the lighter coin). It then takes only one more move to identify the light coin from within that lighter stack. So in two weighings, we can find a single light coin from a set of 3 × 3 = 9.

By extension, it would take only three weighings to find the odd light coin among 27 coins, and four weighings to find it from 81 coins.

Twelve-coin problem

[edit]A more complex version has twelve coins, eleven of twelve of which are identical. If one is different, we don't know whether it is heavier or lighter than the others. This time the balance may be used three times to determine if there is a unique coin—and if there is, to isolate it and determine its weight relative to the others. (This puzzle and its solution first appeared in an article in 1945.[2]) The problem has a simpler variant with three coins in two weighings, and a more complex variant with 39 coins in four weighings.

Solution

[edit]This problem has more than one solution. One is easily scalable to a higher number of coins by using base-three numbering: labelling each coin with a different number of three digits in base three, and positioning at the n-th weighing all the coins that are labelled with the n-th digit identical to the label of the plate (with three plates, one on each side of the scale labelled 0 and 2, and one off the scale labelled 1).[4] Other step-by-step procedures are similar to the following. It is less straightforward for this problem, and the second and third weighings depend on what has happened previously, although that need not be the case (see below).

- Four coins are put on each side. There are two possibilities:

- 1. One side is heavier than the other. If this is the case, remove three coins from the heavier side, move three coins from the lighter side to the heavier side, and place three coins that were not weighed the first time on the lighter side. (Remember which coins are which.) There are three possibilities:

- 1.a) The same side that was heavier the first time is still heavier. This means that either the coin that stayed there is heavier or that the coin that stayed on the lighter side is lighter. Balancing one of these against one of the other ten coins reveals which of these is true, thus solving the puzzle.

- 1.b) The side that was heavier the first time is lighter the second time. This means that one of the three coins that went from the lighter side to the heavier side is the light coin. For the third attempt, weigh two of these coins against each other: if one is lighter, it is the unique coin; if they balance, the third coin is the light one.

- 1.c) Both sides are even. This means that one of the three coins that was removed from the heavier side is the heavy coin. For the third attempt, weigh two of these coins against each other: if one is heavier, it is the unique coin; if they balance, the third coin is the heavy one.

- 2. Both sides are even. If this is the case, all eight coins are identical and can be set aside. Take the four remaining coins and place three on one side of the balance. Place 3 of the 8 identical coins on the other side. There are three possibilities:

- 2.a) The three remaining coins are lighter. In this case you now know that one of those three coins is the odd one out and that it is lighter. Take two of those three coins and weigh them against each other. If the balance tips then the lighter coin is the odd one out. If the two coins balance then the third coin not on the balance is the odd one out and it is lighter.

- 2.b) The three remaining coins are heavier. In this case you now know that one of those three coins is the odd one out and that it is heavier. Take two of those three coins and weigh them against each other. If the balance tips then the heavier coin is the odd one out. If the two coins balance then the third coin not on the balance is the odd one out and it is heavier.

- 2.c) The three remaining coins balance. In this case you just need to weigh the remaining coin against any of the other 11 coins and this tells you whether it is heavier, lighter, or the same.

Variations

[edit]Given a population of 13 coins in which it is known that 1 of the 13 is different (mass) from the rest, it is simple to determine which coin it is with a balance and 3 tests as follows:

- 1) Subdivide the coins in to 2 groups of 4 coins and a third group with the remaining 5 coins.

- 2) Test 1, Test the 2 groups of 4 coins against each other:

- a. If the coins balance, the odd coin is in the population of 5 and proceed to test 2a.

- b. The odd coin is among the population of 8 coins, proceed in the same way as in the 12 coins problem.

- 3) Test 2a, Test 3 of the coins from the group of 5 coins against any 3 coins from the population of 8 coins:

- a. If the 3 coins balance, then the odd coin is among the remaining population of 2 coins. Test one of the 2 coins against any other coin; if they balance, the odd coin is the last untested coin, if they do not balance, the odd coin is the current test coin.

- b. If the 3 coins do not balance, then the odd coin is from this population of 3 coins. Pay attention to the direction of the balance swing (up means the odd coin is light, down means it is heavy). Remove one of the 3 coins, move another to the other side of the balance (remove all other coins from balance). If the balance evens out, the odd coin is the coin that was removed. If the balance switches direction, the odd coin is the one that was moved to the other side, otherwise, the odd coin is the coin that remained in place.

With a reference coin

[edit]If there is one authentic coin for reference then the suspect coins can be thirteen. Number the coins from 1 to 13 and the authentic coin number 0 and perform these weighings in any order:

- 0, 1, 4, 5, 6 against 7, 10, 11, 12, 13

- 0, 2, 4, 10, 11 against 5, 8, 9, 12, 13

- 0, 3, 8, 10, 12 against 6, 7, 9, 11, 13

If the scales are only off balance once, then it must be one of the coins 1, 2, 3—which only appear in one weighing. If there is never balance then it must be one of the coins 10–13 that appear in all weighings. Picking out the one counterfeit coin corresponding to each of the 27 outcomes is always possible (13 coins one either too heavy or too light is 26 possibilities) except when all weighings are balanced, in which case there is no counterfeit coin (or its weight is correct). If coins 0 and 13 are deleted from these weighings they give one generic solution to the 12-coin problem.

If two coins are counterfeit, this procedure, in general, does not pick either of these, but rather some authentic coin. For instance, if both coins 1 and 2 are counterfeit, either coin 4 or 5 is wrongly picked.

Without a reference coin

[edit]In a relaxed variation of this puzzle, one only needs to find the counterfeit coin without necessarily being able to tell its weight relative to the others. In this case, clearly any solution that previously weighed every coin at some point can be adapted to handle one extra coin. This coin is never put on the scales, but if all weighings are balanced it is picked as the counterfeit coin. It is not possible to do any better, since any coin that is put on the scales at some point and picked as the counterfeit coin can then always be assigned weight relative to the others.

A method which weighs the same sets of coins regardless of outcomes lets one either

- (among 12 coins A–L) conclude if they all weigh the same, or find the odd coin and tell if it is lighter or heavier, or

- (among 13 coins A–M) find the odd coin, and, at 12/13 probability, tell if it is lighter or heavier (for the remaining 1/13 probability, just that it is different).

The three possible outcomes of each weighing can be denoted by "\" for the left side being lighter, "/" for the right side being lighter, and "–" for both sides having the same weight. The symbols for the weighings are listed in sequence. For example, "//–" means that the right side is lighter in the first and second weighings, and both sides weigh the same in the third weighing. Three weighings give the following 33 = 27 outcomes. Except for "–––", the sets are divided such that each set on the right has a "/" where the set on the left has a "\", and vice versa:

/// \\\ \// /\\ /\/ \/\ //\ \\/ \/– /\– –\/ –/\ /–\ \–/ \\– //– –\\ –// \–\ /–/ /–– \–– –/– –\– ––/ ––\ –––

As each weighing gives a meaningful result only when the number of coins on the left side is equal to the number on the right side, we disregard the first row, so that each column has the same number of "\" and "/" symbols (four of each). The rows are labelled, the order of the coins being irrelevant:

\// A light /\\ A heavy

/\/ B light \/\ B heavy

//\ C light \\/ C heavy

\/– D light /\– D heavy

–\/ E light –/\ E heavy

/–\ F light \–/ F heavy

\\– G light //– G heavy

–\\ H light –// H heavy

\–\ I light /–/ I heavy

/–– J light \–– J heavy

–/– K light –\– K heavy

––/ L light ––\ L heavy

––– M either lighter or heavier (13-coin case),

or all coins weigh the same (12-coin case)

Using the pattern of outcomes above, the composition of coins for each weighing can be determined; for example the set "\/– D light" implies that coin D must be on the left side in the first weighing (to cause that side to be lighter), on the right side in the second, and unused in the third:

1st weighing: left side: ADGI, right side: BCFJ 2nd weighing: left side: BEGH, right side: ACDK 3rd weighing: left side: CFHI, right side: ABEL

The outcomes are then read off the table. For example, if the right side is lighter in the first two weighings and both sides weigh the same in the third, the corresponding code "//– G heavy" implies that coin G is the odd one, and it is heavier than the others.[5]

Generalization to multiple scales

[edit]In another generalization of this problem, we have two balance scales that can be used in parallel. For example, if you know exactly one coin is different but do not know if it is heavier or lighter than a normal coin, then in rounds, you can solve the problem with at most coins.[6]

Generalization to multiple unknown coins

[edit]The generalization of this problem is described in Chudnov.[7]

Let be the -dimensional Euclidean space and be the inner product of vectors and from For vectors and subsets the operations and are defined, respectively, as ; , , By we shall denote the discrete [−1; 1]-cube in ; i.e., the set of all sequences of length over the alphabet The set is the discrete ball of radius (in the Hamming metric ) with centre at the point Relative weights of objects are given by a vector which defines the configurations of weights of the objects: the th object has standard weight if the weight of the th object is greater (smaller) by a constant (unknown) value if (respectively, ). The vector characterizes the types of objects: the standard type, the non-standard type (i.e., configurations of types), and it does not contain information about relative weights of non-standard objects.

A weighing (a check) is given by a vector the result of a weighing for a situation is The weighing given by a vector has the following interpretation: for a given check the th object participates in the weighing if ; it is put on the left balance pan if and is put on the right pan if For each weighing , both pans should contain the same number of objects: if on some pan the number of objects is smaller than as it should be, then it receives some reference objects. The result of a weighing describes the following cases: the balance if , the left pan outweighs the right one if , and the right pan outweighs the left one if The incompleteness of initial information about the distribution of weights of a group of objects is characterized by the set of admissible distributions of weights of objects which is also called the set of admissible situations, the elements of are called admissible situations.

Each weighing induces the partition of the set by the plane (hyperplane) into three parts , and defines the corresponding partition of the set where

Definition 1. A weighing algorithm (WA) of length is a sequence where is the function determining the check at each th step, of the algorithm from the results of weighings at the previous steps ( is a given initial check).

Let be the set of all -syndromes and be the set of situations with the same syndrome ; i.e., ;

Definition 2. A WA is said to: a) identify the situations in a set if the condition is satisfied for all b) identify the types of objects in a set if the condition is satisfied for all

It is proved in [7] that for so-called suitable sets an algorithm of identification the types identifies also the situations in

As an example the perfect dynamic (two-cascade) algorithms with parameters are constructed in [7] which correspond to the parameters of the perfect ternary Golay code (Virtakallio-Golay code). At the same time, it is established that a static WA (i.e. weighting code) with the same parameters does not exist.

Each of these algorithms using 5 weighings finds among 11 coins up to two counterfeit coins which could be heavier or lighter than real coins by the same value. In this case the uncertainty domain (the set of admissible situations) contains situations, i.e. the constructed WA lies on the Hamming bound for and in this sense is perfect.

To date it is not known whether there are other perfect WA that identify the situations in for some values of . Moreover, it is not known whether for some there exist solutions for the equation (corresponding to the Hamming bound for ternary codes) which is, obviously, necessary for the existence of a perfect WA. It is only known that for there are no perfect WA, and for this equation has the unique nontrivial solution which determines the parameters of the constructed perfect WA.

References

[edit]- ^ Smith, C.A.B. (February 1947). "The Counterfeit Coin Problem". Mathematical Gazette. 31 (293): 31–39. doi:10.2307/3608991. JSTOR 3608991.

- ^ a b Grossman, Howard D. (September–December 1945). "The twelve-coin problem". Scripta Mathematica. 11 (3–4): 360–361.

- ^ a b Guy, Richard; Nowakowski, Richard (February 1995). "Coin-Weighing Problems". The American Mathematical Monthly. 102 (2): 164–167. doi:10.1080/00029890.1995.11990553.

- ^ Dyson, Freeman J. (1946). "1931. The Problem of the Pennies". The Mathematical Gazette. 30 (291): 231–234. doi:10.2307/3611225. JSTOR 3611225.

- ^ "Math Forum - Ask Dr. Math". mathforum.org. Archived from the original on 2002-06-12.

- ^ Khovanova, Tanya (2013). "Solution to the Counterfeit Coin Problem and its Generalization". arXiv:1310.7268 [math.HO].

- ^ a b c Chudnov, Alexander M. (2015). "Weighing algorithms of classification and identification of situations". Discrete Mathematics and Applications. 25 (2): 69–81. doi:10.1515/dma-2015-0007. S2CID 124796871.

External links

[edit]Balance puzzle

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Objective

A balance puzzle is a logic puzzle centered on using a two-pan balance scale to detect anomalies, such as counterfeit coins, within a collection of seemingly identical objects. Typically, the setup involves a set of coins where most are genuine and weigh the same, but one or more are fake and either lighter or heavier. The puzzle requires identifying the counterfeit item(s) and determining their weight deviation through strategic weighings.[4] The primary objective is to devise an optimal strategy that minimizes the number of weighings needed to solve the puzzle, leveraging the scale's ternary outcomes: left pan heavier (left pan down), right pan heavier (right pan down), or equal weight (balances). This approach exploits the information gained from each weighing to narrow down possibilities efficiently. Key assumptions include that all genuine items have identical weight, counterfeits deviate consistently (either all lighter or all heavier, but unknown in advance), and there is no prior information about the deviation's direction or magnitude beyond it being noticeable on the scale.[5] These puzzles originated in recreational mathematics during the 1940s, with the earliest known counterfeit coin variant published in the American Mathematical Monthly in January 1945 by E. D. Schell, involving eight coins and two weighings to find a lighter fake. They were popularized in the 1940s and 1950s through mathematical journals and puzzle collections, drawing on earlier weighing challenges like those in Claude Gaspard Bachet de Méziriac's 1624 work Problèmes plaisants et délectables. Classic instances, such as the nine- or twelve-coin problems, illustrate the genre but are explored in detail elsewhere.[5]Balance Scale Mechanics

A balance scale in these puzzles consists of two pans suspended from a beam, allowing comparison of the total weights placed on each side. When weights are added, the scale tips toward the heavier side or remains level if the weights are equal, yielding one of three possible results per weighing: left pan down (left heavier), right pan down (right heavier), or balanced. This mechanism operates on relative comparisons rather than measuring absolute values, and multiple items can be placed on either pan to test groups simultaneously.[4] The ternary nature of the outcomes introduces a base-3 logic to the problem-solving process, where each weighing partitions the set of possible scenarios into three subsets of roughly equal size—one for each result—to maximize information gain. This division facilitates a branching search akin to a ternary decision tree, where subsequent weighings refine the possibilities based on prior results, often adaptively. Such structure underpins the efficiency of solutions in classic problems like identifying a counterfeit coin among a dozen.[4] Despite its utility, the scale's limitations constrain its application: it reveals only the direction of imbalance without quantifying the weight difference, precluding direct measurement of individual items or precise deviations. Group comparisons are permitted, but the absence of a numerical output means strategies must rely solely on qualitative tilts or balances to infer anomalies.[4] A key prerequisite for tackling these puzzles is recognizing the scale's information capacity: with weighings, up to coins can be distinguished when one is counterfeit and its deviation direction (heavier or lighter) is unknown. This bound arises because the possible outcome sequences exclude the all-balanced case (corresponding to all genuine coins), leaving sequences to identify among scenarios (N choices for the fake coin, each with two directions).[4]Classic Coin-Weighing Problems

Nine-Coin Problem

The nine-coin problem is a classic instance of a coin-weighing balance puzzle, featuring nine apparently identical coins where eight are genuine and weigh the same, while one is counterfeit and lighter than the genuine ones. The challenge is to identify the counterfeit coin and confirm its lighter nature using a balance scale in exactly two weighings.[4] This setup presents nine possible scenarios, one for each coin being the lighter counterfeit. Two weighings on a balance scale produce possible outcome sequences (left side down, right side down, or balance for each weighing), providing exactly the information needed to distinguish among the nine possibilities, assuming there is always one counterfeit.[4] The coins are conventionally labeled 1 through 9 for reference. The initial weighing typically divides them into three groups of three coins each, leveraging the balance scale's ability to yield ternary outcomes for efficient information gain.[4] Two weighings represent the minimal number required, as a single weighing yields only three outcomes, insufficient to resolve nine possibilities.[4]Five-Coin Problem

The five-coin problem is a variant of the coin-weighing balance puzzle, featuring five apparently identical coins where four are genuine and weigh the same, while one is counterfeit and lighter than the genuine ones. The challenge is to identify the counterfeit coin using a balance scale in a maximum of two weighings in the worst case. It is impossible in one weighing, as one weighing has only three possible outcomes but there are five possibilities to distinguish. This setup presents five possible scenarios. Two weighings produce possible outcome sequences, sufficient to distinguish among the five possibilities.Twelve-Coin Problem

The twelve-coin problem involves twelve apparently identical coins, eleven of which are genuine and weigh the same, while one is counterfeit and either lighter or heavier than the others; the objective is to identify the counterfeit coin and determine whether it is lighter or heavier using a balance scale in exactly three weighings.[6] This setup presents 24 possible scenarios, as there are 12 choices for the counterfeit coin and 2 possibilities for its weight deviation (heavier or lighter).[6] With three weighings, the balance scale produces 27 possible outcome sequences (left heavy, right heavy, or balance for each weighing, or ), which is sufficient to distinguish among the 24 scenarios while leaving three outcomes unused, often corresponding to the impossibility of all coins being genuine under the problem's assumptions.[6] A common initial approach divides the coins into three groups of four, weighing four against four while setting the remaining four aside; the result—balance or imbalance—narrows the suspects to either the unweighed group or one side of the weighed groups, guiding the subsequent two weighings.[7] This strategy leverages the ternary logic inherent in balance scale mechanics, where each weighing ternary-partitions the possibilities.[6] The twelve-coin problem holds significance as a benchmark for information-theoretic efficiency in decision problems, demonstrating how 27 outcomes can resolve up to 13 coins if a known genuine is available, but exactly 12 without it, as proven in early analyses.[8] It has a documented history dating to at least 1945 in print and was elegantly generalized by physicist Freeman Dyson in 1946, influencing subsequent puzzle literature and variants in logic and combinatorics.[9][10]Detailed Solutions

Strategy for Nine Coins

The strategy for the classic nine-coin problem identifies the lighter counterfeit coin among nine using two adaptive weighings on a balance scale. This resolves the 9 possibilities with the 9 outcomes from two weighings (each with 3 results). Label the coins 1 through 9. Divide them into three groups: A (1,2,3), B (4,5,6), C (7,8,9). The first weighing compares group A against group B.-

Balance: The lighter coin is in group C. For the second weighing, compare 7 against 8.

- If 7 < 8, 7 is lighter.

- If 8 < 7, 8 is lighter.

- If balanced, 9 is lighter.[1]

-

A lighter than B (A < B): The lighter coin is in group A. For the second weighing, compare 1 against 2.

- If 1 < 2, 1 is lighter.

- If 2 < 1, 2 is lighter.

- If balanced, 3 is lighter.[1]

- B lighter than A (B < A): Symmetric to the A lighter case; the lighter coin is in group B, and the second weighing compares two coins from B analogously.[1]

Strategy for Five Coins

The strategy identifies the lighter counterfeit coin among five using at most two weighings on a balance scale. This is possible because two weighings yield up to 9 outcomes (3² = 9), sufficient to distinguish 5 possibilities, whereas one weighing provides only 3 outcomes, making it impossible in a single weighing. Label the coins 1 through 5. For the first weighing, compare 1+2 against 3+4.- Balance: Coin 5 is lighter, identified in one weighing.

-

1+2 lighter than 3+4: The lighter coin is among 1 or 2. For the second weighing, compare 1 against 2.

- If 1 < 2, 1 is lighter.

- If 2 < 1, 2 is lighter.

- Balance cannot occur, as one coin is lighter.

- 3+4 lighter than 1+2: Symmetric to the previous case; the lighter coin is among 3 or 4. Weigh 3 against 4 to identify the lighter one.

Strategy for Twelve Coins

The strategy for the twelve-coin problem uses adaptive weighings to identify the counterfeit (heavier or lighter) in three steps, distinguishing 24 possibilities with 27 outcomes. A signed labeling approach (+ for potential heavy on left or light on right, etc.) balances the scale design.[11] Label coins 1 through 12. First weighing: 1–4 vs. 5–8. If balance, counterfeit in 9–12; 1–8 genuine. Second weighing: 1–3 vs. 9–11.- Balance: 12 counterfeit; third: 12 vs. 1 (heavier/light determines type).

- 9–11 heavier: one of 9–11 heavy; third: 9 vs. 10 (heavier is counterfeit, or balance means 11 heavy).

- 9–11 lighter: one of 9–11 light; third: 9 vs. 10 (lighter is, or balance 11 light).[12]

- Balance: counterfeit is 3 heavy or 4 heavy (wait, adjust: actually for this grouping, assuming symmetry from source). Wait, to match valid: use 1,2,5 vs 3,4,6 for second? No, following source variant.

- Left > right: 2L,5H,6H (left heavy by 2L right light, or 5H/6H left heavy). Third: 5 vs 6 (heavier H, balance 2L by 2 vs 9 lighter).

- Left < right: 1L,7H,8H. Third: 7 vs 8 (heavier H, balance 1L).

- Balance: 3L or 4L. Third: 3 vs 4 (lighter is L).

![{\displaystyle [\mathrm {e} ^{1},\mathrm {e} ^{2}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/720e187783b3816d08327b56ac6fe5cf73976295)

![{\displaystyle s(\mathrm {x} ;\mathrm {h} )=sign([\mathrm {x} ;\mathrm {h} ]).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/baf6786534be971bad9d1e2015e7490bd6599d2d)

![{\displaystyle r(\mathrm {h} )=[\mathrm {h} ;1,\dots ,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9bd6c8a71c637921d7d2283b858ea1f5b051542e)

![{\displaystyle [\mathrm {x} ;\mathrm {h} ]=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5196f49ec53845f777a09f58d327196e180449a0)