Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Logic puzzle

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

| Part of a series on |

| Puzzles |

|---|

|

A logic puzzle is a puzzle deriving from the mathematical field of deduction.

History

[edit]The logic puzzle was first produced by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, who is better known under his pen name Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. In his book The Game of Logic he introduced a game to solve problems such as confirming the conclusion "Some greyhounds are not fat" from the statements "No fat creatures run well" and "Some greyhounds run well".[1] Puzzles like this, where we are given a list of premises and asked what can be deduced from them, are known as syllogisms.[citation needed] Dodgson goes on to construct much more complex puzzles consisting of up to 8 premises.[citation needed]

In the second half of the 20th century mathematician Raymond M. Smullyan continued and expanded the branch of logic puzzles with books such as The Lady or the Tiger?, To Mock a Mockingbird and Alice in Puzzle-Land. He popularized the "knights and knaves" puzzles, which involve knights, who always tell the truth, and knaves, who always lie.[citation needed]

There are also logic puzzles that are completely non-verbal in nature. Some popular forms include Sudoku, which involves using deduction to correctly place numbers in a grid; the nonogram, also called "Paint by Numbers", which involves using deduction to correctly fill in a grid with black-and-white squares to produce a picture; and logic mazes, which involve using deduction to figure out the rules of a maze.[2]

Logic grid puzzles

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

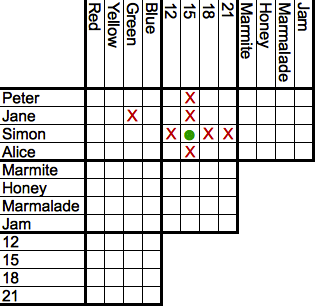

Another form of logic puzzle, popular among puzzle enthusiasts and available in magazines dedicated to the subject, is a format in which the set-up to a scenario is given, as well as the object (for example, determine who brought what dog to a dog show, and what breed each dog was), certain clues are given ("neither Misty nor Rex is the German Shepherd"), and then the reader fills out a matrix with the clues and attempts to deduce the solution. These are often referred to as "logic grid" puzzles. The data set of a logic grid puzzles can be any number of categories, but are limited by the corresponding increase in complexity, with most having only two, three, or even four categories.

While designed more as a table-based puzzle than a matrix, the most famous example of a logic-grid puzzle may be the so-called Zebra Puzzle, which asks the question Who Owned the Zebra?.

Common in logic puzzle magazines are derivatives of the logic grid puzzle called "table puzzles" that are deduced in the same manner as grid puzzles, but lack the grid either because a grid would be too large, or because some other visual aid is provided. For example, a map of a town might be present in lieu of a grid in a puzzle about the location of different shops.

See also

[edit]- Category:Logic puzzles, a list of different logic puzzles

- List of puzzle video games

- Logic programming

- Mechanical puzzle

- Recreational mathematics

- Muddy Children Puzzle

- Survo puzzle

- Murdle

References

[edit]- ^ Carroll 1886, p. 53 #24.

- ^ "Techniques for Solving Mazes - Puzzle Genius". Retrieved 2025-09-02.

Sources

[edit]- Carroll, Lewis (1886). The Game of Logic. London: Macmillan.

Logic puzzle

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Definition

A logic puzzle is a type of intellectual challenge that requires deductive reasoning from a set of given premises to deduce a unique solution, typically through the application of constraints to eliminate invalid possibilities.[7] These puzzles emphasize systematic inference, where solvers build conclusions step by step based solely on the provided information, without needing external knowledge or chance.[2] Unlike mathematical proofs, which aim to establish general truths applicable across infinite or broad domains using formal rigor, logic puzzles are confined to finite, self-contained scenarios designed for targeted problem-solving.[7] In contrast to riddles, which often rely on wordplay, misdirection, or veiled meanings for resolution, logic puzzles prioritize explicit logical inference and consistency checking over linguistic tricks.[7] The fundamental components of a logic puzzle include clues that supply the initial premises, variables representing entities such as people, objects, or positions, and relations that define possible connections or assignments among them, such as ownership or adjacency.[8] These elements form a structured framework where interdependencies guide the elimination process toward the sole valid outcome.[2]Key Features and Elements

Logic puzzles are characterized by a finite set of possibilities, typically represented through discrete elements such as categories, items, or positions that solvers must assign or match according to given rules.[9] These elements form a bounded search space, ensuring that the puzzle can be exhaustively explored without infinite options, as seen in grid-based variants where categories contain a fixed number of unique items (e.g., four clients, four prices, and four masseuses in a standard setup).[9] Interdependent clues provide the constraints that link these elements across categories, creating a web of relationships that must be resolved collectively rather than in isolation; for instance, a clue stating "Hannah paid more than Teri’s client" ties specific entities together, forcing deductions that propagate through the entire structure.[9] Well-formed logic puzzles emphasize ambiguity avoidance by guaranteeing a unique solution verifiable solely through logical deduction, eliminating the need for trial-and-error or external knowledge.[10] This uniqueness is a core design principle, as multiple solutions would undermine the deductive process, leading to inconsistencies or reliance on arbitrary choices; puzzle creators like those at Nikoli enforce absolute uniqueness to maintain fairness and solvability.[10] Constraints such as one-to-one mappings—where each item in one category pairs exclusively with one item in another—further enforce this, preventing overlaps and ensuring every element is utilized exactly once in the final arrangement.[9] Cognitively, logic puzzles demand pattern recognition to identify recurring structures or implications within the clues and partial solutions, such as spotting unavoidable placements in a grid.[7] Solvers engage in hypothesis testing by tentatively assigning elements and verifying them against the rules, refining or discarding ideas based on consistency, which mirrors formal proof construction.[7] A key requirement is the avoidance of assumptions beyond the provided clues, training disciplined reasoning that relies only on explicit information to prevent errors from extraneous inferences.[11]Historical Development

Ancient and Early Examples

The earliest known examples of logic puzzles trace back to ancient Mesopotamia, where riddles inscribed on cuneiform tablets required deductive reasoning to interpret metaphors and scenarios from daily life, politics, and nature. Dating to around 1500 BCE in the Old Babylonian period, these riddles, such as a political satire involving a ruler's deceit, challenged scribes to apply logical inference in educational contexts like surveyor training.[12][13] These proto-logic forms prefigure modern puzzles by emphasizing constraint-based deduction without explicit rules. In ancient Greece, Aristotle developed syllogistic logic in the 4th century BCE, laying the groundwork for formal deduction through structured arguments consisting of two premises leading to a conclusion, such as "All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal." His works in the Organon formalized categorical propositions and syllogisms, influencing philosophical and logical reasoning for centuries and serving as a basis for later puzzle constructions.[14] During the 5th century BCE, Zeno of Elea developed paradoxes that probed the foundations of motion, space, and infinity through seemingly contradictory logical arguments. Notable among them is the Achilles and the tortoise paradox, where Achilles cannot overtake a slower tortoise due to infinite subdivisions of distance, forcing readers to confront assumptions about continuity and summation.[15] Similarly, the dichotomy paradox argues that to traverse any distance, one must first cover half, then half of the remainder, ad infinitum, rendering motion impossible—a challenge resolved only centuries later through calculus but highlighting early rigorous logical debate.[15] Medieval Islamic scholarship advanced mechanical logic through ingenious devices that incorporated automated sequences and feedback mechanisms, akin to puzzle-like automata. In the 9th century CE, the Banū Mūsā brothers—Muḥammad, Aḥmad, and al-Ḥasan—authored The Book of Ingenious Devices (c. 850 CE), detailing around 100 inventions including self-regulating fountains and trick vessels that operated via hidden logical principles, such as siphons triggering based on water levels to surprise users.[16] These contraptions, blending engineering with recreational intellect, demonstrated proto-computational logic in physical form, influencing later automata designs.[17]Modern Evolution and Popularization

In the 19th century, Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) bridged verbal and formal logic with playful word games that demanded systematic transformation and inference. His "doublets," introduced in 1879, required changing one word into another by altering a single letter per step while forming valid English words, as in transforming "head" to "tail" via intermediates like "heal" and "teal."[4] Published in works like The Game of Logic (1886), these puzzles used diagrams to visualize syllogisms, serving as accessible precursors to structured deduction in recreational mathematics.[4] The modern era of logic puzzles began in the early 20th century with the pioneering work of British puzzle designer Henry Ernest Dudeney, whose collections such as The Canterbury Puzzles (1907) and Amusements in Mathematics (1917) systematized recreational logic problems, drawing on earlier traditions while introducing innovative mechanical and geometrical challenges that influenced subsequent creators.[18] Dudeney's contributions, including the first crossnumber puzzle in 1926, helped elevate logic puzzles from casual diversions to structured intellectual exercises, fostering a growing audience through newspaper and magazine publications.[19] In the 1930s, the launch of Dell Publishing's puzzle magazines marked a significant milestone in mass dissemination, beginning with Dell Crossword Puzzles in 1931 and expanding to include logic and math-based formats that reached millions of readers annually.[20] This periodical tradition continued unabated, providing consistent outlets for logic puzzles amid the rise of print media. The mid-20th century saw further popularization through Martin Gardner's "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific American, which ran from 1957 to 1980 and introduced concepts like polyominoes and Conway's Game of Life to a broad readership, sparking widespread interest in recreational mathematics.[21] Complementing this, Raymond Smullyan's books in the 1970s, such as What Is the Name of This Book? (1978) and The Chess Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes (1979), blended logic with narrative storytelling, making deductive reasoning accessible and engaging for non-specialists.[22] A pivotal development came in 1979 with the invention of Sudoku (originally "Number Place") by American architect Howard Garns, published in Dell Math Puzzles & Logic Problems, which combined grid constraints with numerical deduction in a format ripe for global appeal.[23] Though initially modest, Sudoku exploded in popularity after its 1984 adoption and renaming by Japan's Nikoli magazine, culminating in worldwide mania by 2005 following its introduction in The Times (London) and major U.S. outlets, with sales of puzzle books surpassing millions and inspiring international competitions.[24] The digital revolution from the 1990s onward transformed logic puzzles by enabling computer generation and interactive delivery, with early examples like Microsoft Minesweeper (1990) introducing grid-based deduction to personal computers. Software advancements, such as Hong Kong judge Wayne Gould's 1997 program for creating unique Sudoku variants, facilitated endless puzzle variations and powered the shift to apps and online platforms in the 2000s, dramatically increasing accessibility via mobile devices and broadening participation beyond print media.[24]Major Types

Grid and Constraint-Based Puzzles

Grid and constraint-based puzzles, often referred to as logic grid puzzles, are deduction-based challenges that involve matching elements across multiple categories using provided clues to satisfy all constraints. These puzzles typically consist of an equal number of elements in each category—such as suspects, locations, or attributes—and require identifying the unique one-to-one correspondences that fulfill the conditions. The format draws from constraint satisfaction problems, where clues impose relational restrictions, and the goal is to derive the complete assignment through iterative elimination.[9] The core structure utilizes a cross-referencing grid, a tabular matrix with rows for one category (e.g., individuals) and columns for others (e.g., professions, items), enabling visual tracking of possibilities. Solvers mark cells to indicate impossibilities (often with an "X") based on contradictory clues or confirmed matches (e.g., with a checkmark), progressively narrowing options until only valid pairings remain. This method leverages bijectivity—ensuring each element pairs uniquely across categories—and transitivity in deductions, such as inferring that if A relates to B and B excludes C, then A excludes C. For illustration, a simplified 3x3 grid for matching three friends to drinks and hobbies might start empty and evolve as clues eliminate options:| Friend | Tea | Coffee | Hobby1 | Hobby2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alice | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Bob | X | ? | ? | X |

| Carol | ? | ? | X | ? |