Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

CAD/CAM dentistry

View on Wikipedia

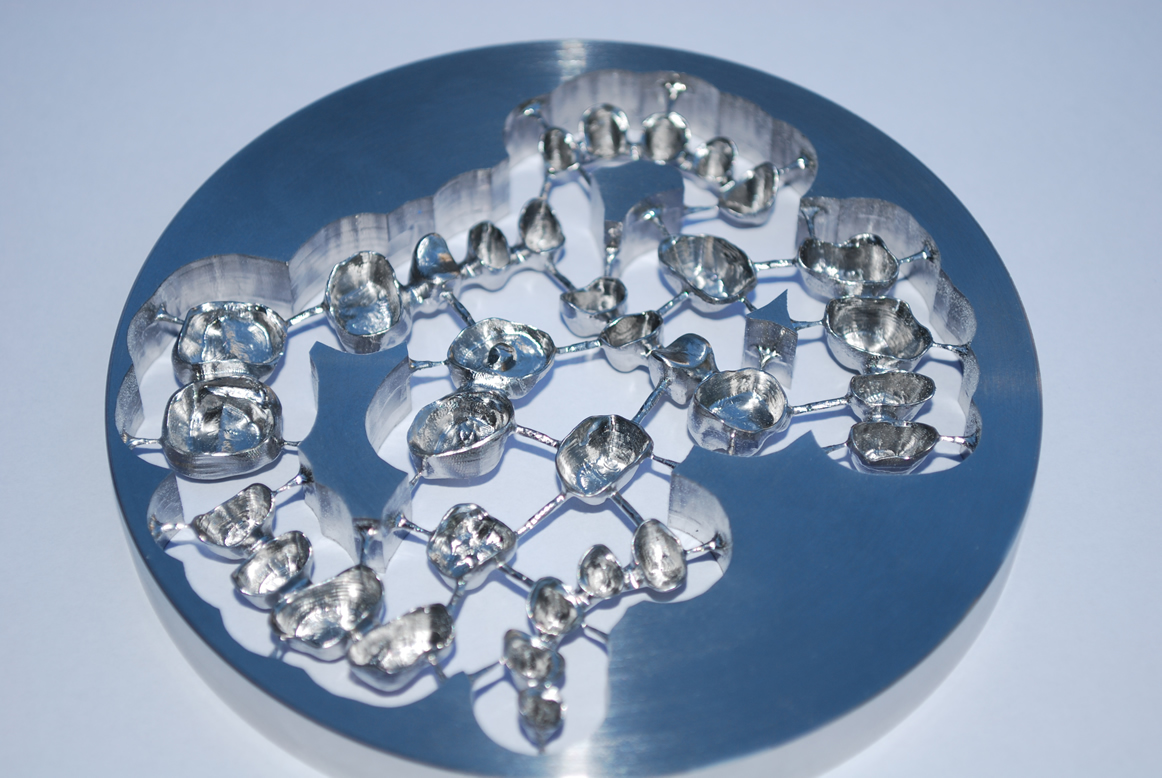

CAD/CAM dentistry is a field of dentistry and prosthodontics using CAD/CAM (computer-aided-design and computer-aided-manufacturing) to improve the design and creation of dental restorations,[1][2] especially dental prostheses, including crowns, crown lays, veneers, inlays and onlays, fixed dental prostheses (bridges), dental implant supported restorations, dentures (removable or fixed), and orthodontic appliances. CAD/CAM technology allows the delivery of a well-fitting, aesthetic, and a durable prostheses for the patient.[3] CAD/CAM complements earlier technologies used for these purposes by any combination of increasing the speed of design and creation; increasing the convenience or simplicity of the design, creation, and insertion processes; and making possible restorations and appliances that otherwise would have been infeasible. Other goals include reducing unit cost and making affordable restorations and appliances that otherwise would have been prohibitively expensive. However, to date, chairside CAD/CAM often involves extra time on the part of the dentist, and the fee is often at least two times higher than for conventional restorative treatments using lab services.

Like other CAD/CAM fields, CAD/CAM dentistry uses subtractive processes (such as CNC milling) [4] and additive processes (such as 3D printing) to produce physical instances from 3D models.

Some mentions of "CAD/CAM" and "milling technology" in dental technology have loosely treated those two terms as if they were interchangeable, largely because before the 2010s, most CAD/CAM-directed manufacturing was CNC cutting, not additive manufacturing, so CAD/CAM and CNC were usually coinstantiated; but whereas this loose/imprecise usage was once somewhat close to accurate, it no longer is, as the term "CAD/CAM" does not specify the method of production except that whatever method is used takes input from CAD/CAM,[5] and today additive and subtractive methods are both widely used.

Application of CAD/CAM in dentistry

[edit]Computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacture (CAM) is a process where non-digital data is captured, converted into a digital format, edited as necessary, and subsequently converted back into a physical form with the exact dimensions and materials specified during the digital design process, usually by either 3D printing or milling.[6] This set of stages is known as a "digital workflow".[7]

CAD/CAM may be used to provide a machine-led means of fabricating dental prostheses that are used to restore or replace teeth. This is an alternative to the traditional process of prosthesis fabrication using physical techniques, in which the dentist makes an impression of the site that is to be restored. This is then transported to the laboratory where a study model is made. On that model, an imitation of the final design is made using wax – known as a wax up – which represents the size and shape of the finished dental prosthesis. The wax is then encased in an investment mold, burned out and replaced with the desired material as part of lost wax casting.[8] CAD/CAM makes such procedures unnecessary for the impression is recorded digitally and the manufacture of the appliance is accompanied by additive (3D printing) or subtractive (milling) means.

Examples of dental prostheses that can be manufactured using this system include:[8]

- Study models

- Orthodontic devices

- Cuspal coverage restorations

- Fixed dental prostheses

- Veneers

- Removable denture frameworks

- Implant planning and fabrication

History

[edit]Although CAD/CAM dentistry was used in the mid-1980s, early efforts were considered a cumbersome novelty, requiring an inordinate amount of time to produce a viable product. This inefficiency prevented its use within dental offices and limited it to labside use (that is, used within dental laboratories). As adjunctive techniques, software, and materials improved, the chairside use of CAD/CAM (use within dental offices/surgeries) increased.[9] For example, the commercialization of Cerec by Sirona made CAD/CAM available to dentists who formerly would not have had avenues for using it.

The first CAD/CAM system used in dentistry was produced in the 1970s by Professor François Duret [10][11] and colleagues. The process contains a number of steps. Firstly, an optical impression of the intraoral abutment is obtained by scanning with an intra-oral digitizer. The digitized information is transferred to the monitor where a 3D graphic design is produced. The restoration can then be designed on the computer. The final restoration is then milled from a block. Professor Duret and colleagues subsequently developed the 'sopha system' however this was not widely used, perhaps lacking the accuracy, materials and computer capabilities required in dentistry.[12] The second generation of CADCAM attempted to develop this system further, but struggled to obtain occlusal morphology using an intra oral scanner, so prepared a stone model first before digitising the model.

Development of a various digitizers followed: a laser beam with a position sensitive detector sensor, a contact probe and a laser with a charged coupled device camera. Due to development of more sophisticated CAD/CAM systems both metal and ceramic restorations could be produced.[12]

Mormann and colleagues later developed a CADCAM system named CEREC, which they used to produce a type of dental restoration called an inlay. The inlay preparation is scanned using an intra-oral camera. A compact machine used chairside allowed design of the restoration from a ceramic block.[12] The major advantage of this system was the chair side approach allowing same-day restorations.[13] However, this technique was limited in that it couldn't be used for contouring or occlusal patterns. The CEREC system is used widely across the world, and studies have shown long term clinical success.[12]

The Procera system was developed by Anderson and colleagues. They used CADCAM to develop composite veneers. The Procera system later developed as a processing centre connected to satellite digitisers worldwide to produce all ceramic frameworks. This system is used around the world today.[13]

Difference from conventional restoration

[edit]Chairside CAD/CAM restoration typically creates and lutes(bonds) the prosthesis the same day. Conventional prostheses, such as crowns, have temporaries placed for one to several weeks while a dental laboratory or in-house dental lab produces the restoration.[14] The patient returns later to have the temporaries removed and the laboratory-made crown cemented or bonded in place. An in-house CAD/CAM system enables the dentist to create a finished inlay in as little as one hour.[15] CAD/CAM systems use an optical camera to take a virtual impression by creating a 3D image which is imported into a software program and results in a computer-generated cast on which the restoration is designed.[16]

Bonded veneer CAD/CAM restorations are more conservative in their preparation of the tooth. As bonding is more effective on tooth enamel than the underlying dentin, care is taken not to remove the enamel layer. Though one-day service is a benefit that is typically claimed by dentists offering chairside CAD/CAM services, the dentist's time is commonly doubled and the fee is therefore doubled.

Process

[edit]All CAD/CAM systems consist of a computer aided design (CAD) and computer aided manufacture (CAM) stage and the key stages can broadly be summarised as the following:

- Optical/contat scanning that captures the intraoral or extraoral condition of the patient.

- Use of software that can turn the captured images into a digital model to upon which a dental prosthesis can be designed and prepared for fabrication.

- Instruction to devices that can facilitate the conversion of the design into a product by way of 3D printing or milling depending on the CAD/CAM system used.[5]

For a single unit prosthesis, after decayed or broken areas of the tooth are corrected by the dentist, an optical impression is made of the prepared tooth and the surrounding teeth. These images are then turned into a digital model by proprietary software within which the prosthesis is created virtually. The software sends this data to a milling machine where the prosthesis is milled. Stains and glazes can be added to the surfaces of the milled ceramic crown or bridge to correct the otherwise monochromatic appearance of the restoration. The restoration is then adjusted in the patient's mouth and luted or bonded in place.

Integrating optical scan data with cone beam computed tomography datasets within implantology software also enables surgical teams to digitally plan implant placement and fabricate a surgical guide for precise implementation of that plan. Combining CAD/CAM software with 3D images from a 3D imaging system means greater safety and security from any kind of intraoperative mistakes.

Computer-aided design (CAD)

[edit]To design and manufacture a dental prosthesis, the physical space which it will replace within the mouth has to be converted into a digital format. To do this, a digital impression must be taken. This will convert the space into a digital image which must then be converted into a file extension that can be read by the CAD software system being used.[13]

Once in a digital form, the structures within the mouth will be displayed as a 3D image. Using CAD software, the size and shape of the restoration can be virtually altered, thus replacing the wax up stage present in the traditional approach.[12][17]

Digital impressions

[edit]Digital impressions are a means of recording the shape of a patient's dental structures by using scanners. In CAD/CAM's infancy, desktop scanners were used which digitised study models or Dental impressions - indirect representations of the patient's dentition.[18] These devices are also known as extra oral scanners and can be contact or non-contact.[17]

Contact scanners use stylus profilometers that are placed against and run along the contours of an object. The contact of the stylus against the object is represented digitally as a set of co-ordinates (point cloud), which is analyzed by an onboard mathematical algorithm to build up a 3D image of the object (mesh).[7][19]

Non-contact scanners capture the shape of dental structures by using optics, such as light-emitting diodes. Light is emitted from the scanner which hits the object and then reflects into an onboard sensor, usually a charge couple device (CCD) or a position sensing detector (PSD).[12] These reflections allow the scanner to build up a 3D image of the object as with contact scanners [7] Extraoral non-contact scanners can obtain this information by different means, namely: structured light, laser light and confocal microscopy.[17] Contact scanners are more accurate than non-contact scanners but are rarely used anymore because they are slow and their imaging is unnecessarily detailed, ten times what is required for the success of a dental prosthesis.[17]

Intra-oral scanners are a form of non-contact scanners that have grown in popularity due to their ability to digitize a patient's dentition directly in the mouth, avoiding the need for either a physical impression or a plaster study model, as is the case with extraoral scanners. This allows the fabrication of dental prostheses to be a completely digital process from the very first stage. Older scanners require a contrast powder to be placed on all the structures which were to be scanned whereas newer products do not require such a step.[17]

Intra-oral scanners interpret reflected light to produce a 3D image representing the patient's teeth, using systems including:[20]

- Confocal laser scanner microscopy

- Triangulation

- Optical coherent tomography

- Accordion fringe interferometry

- Active wavefront sampling

The file extension most recognised by CAD software is an STL file. This file type records and describes an object's geometry as a series of connected triangles, the density of which, depends upon the "resolution and the mathematical algorithm that was used to create the data".[17] Most available scanners will produce STL files however some produce proprietary file types that can only be interpreted by select CAD software.[17][20]

CAD Software

[edit]CAD software visualises the digital impression captured by extra or intra oral scanners and provides numerous design tools. Popular software packages include Dental System, DentalCAD and CEREC.[17] Some of the most common ways in which the virtual dental prosthesis can be edited are as follows:

- The size and shape of restorations can be adjusted.

- The shape of teeth is often adjusted using dental burs prior to scanning to accommodate a dental prosthesis such as a crown. This is called a preparation and the edge of this is known as the margin. Margins need to be demarcated so that the dental prosthesis finishes flush with the rest of the tooth to reduce the chances of plaque build-up under the prosthesis. Margins can be detected automatically which would normally have to be delineated by a technician visually. They can also be adjusted manually.

- The path of insertion axis can be determined automatically which dictates the direction the dental prosthesis must move to fit into the tooth/mouth.

- Measurements can be made between points on the digital model which can help inform the technician if any modifications to the tooth are needed to accommodate the dental prosthesis. The material must be thick enough to provide adequate strength but also not so thick as to cause the restored tooth to contact the opposing tooth before all other teeth in the arch – this would prop the patient's mouth open and prevent them from being able to bite normally.

Materials used in computer-aided manufacture

[edit]CAD/CAM is a rapidly evolving field, hence the materials in use are always changing. Materials that can be manufactured using CADCAM software currently include metals, porcelain, lithium disilicate, zirconia and resin materials. CAD/CAM restorations are milled from solid blocks of ceramic or composite-resin. If pre-sintered ceramic ingots are used, subsequent sintering to reduce porosity is required and the CAD-CAM technology needs to account for any casting shrinkage during this process. Glass-based restorations can also be manufactured using CAD-CAM. Similar to ceramics, milling of glass ingots occurs and molten glass infiltration is used to reduce porosity.[21] The advantage of materials manufactured by CADCAM is the consistency in quality of restoration when mass produced.

Metals

[edit]Metals such as CoCr and titanium can be manufactured using CADCAM software. Precious metals cannot be machined for a variety of reasons, including expense. Pre-sintered CoCr blocks are available, and requires sintering after to achieve the desired mechanical properties. This method replaces the more traditional lost-wax technique.[22]

Ceramics

[edit]Feldspathic and leucite-reinforced ceramics

[edit]The microstructure of feldspathic and leucite reinforced ceramics is a glassy matrix with crystalline loads. It has low flexural strength, very good optical properties and an advantageous bonding abilities. A major advantage is its good aesthetics, with a variety of shades available and high translucency. However, it is a fragile material and is susceptible to damage by occlusal forces.[22]

Lithium disilicate, zirconium oxide and lithium silicate ceramics

[edit]Lithium disilicate, zirconium oxide and lithium silicate ceramics also have a biphasic structure with crystalline particles dispersed in a glass matrix. They have a high flexural strength, good optical properties and ability to bond. It produces highly aesthetic restorations in a variety of shades is useful as well as its high mechanical strength.[22]

Zirconia

[edit]Zirconia has a polycrystalline structure. It has a high flexural strength. However, both its optical properties and ability to bond are weak. Its main advantage is its mechanical strength.[21] CAD-CAM processing means that polycrystalline zirconia can be utilised for copings and frameworks. Its superior mechanical properties means it can be used for long-span bridgework, cores can be produced in thinner layers and can be utilised in posterior fixed partial dentures.[21] However, the aesthetics of zirconia restorations are not as good as other types of ceramic.

Resin materials

[edit]Three resin materials are available: resin composite, PMMA, and Nano-ceramics. PMMA is made of polymethylmethacrylate polymers with no filler. However, resin composite is composed of inorganic filler in a resin matrix. Similarly, nano-ceramic is nanoparticles embedded in a resin matrix. All three materials have a weak flexural strength and disadvantageous optical properties. However, the ability to bond is very effective. An advantage of these materials is the ability to manufacture them quickly through fast milling, so are great to used for direct composite repairs. However, the aesthetic quality of these materials limit their utility.[21]

Advantages and drawbacks

[edit]CAD/CAM has improved the quality of prostheses in dentistry and standardised the production process. It has increased productivity and the opportunity to work with new materials with a high level of accuracy.[5]

Though CAD/CAM is a major technological advancement, it is important that dentists' technique is suited to CAD/CAM milling. This includes: correct tooth preparation with a continuous preparation margin (which is recognisable to the scanner e.g. in the form of a chamfer); avoiding the use of shoulderless preparations and parallel walls and the use of rounded incisor and occlusal edges to prevent the concentration of tension.[5]

Crowns and bridges require a precise fit on tooth abutments or stumps. Fit accuracy varies according to the CAD/CAD system utilized and from user to user. Some systems are designed to attain higher standards of accuracy than others and some users are more skilled than others. As of 2014[update], 20 new systems were expected to become available by 2020.[23]

Further research is needed to evaluate CAD/CAM technology compared to the other attachment systems (such as ball, magnetic and telescopic systems), as an option for attaching overdentures to implants.[24]

Advantages of CAD/CAM

[edit]The advantages CAD/CAM provides when compared with the traditional laboratory and chairside led techniques are that it 1) allows for use of materials otherwise unavailable in the laboratory; 2) provides cheaper alternatives when compared with conventional materials; 3) decreases labour cost and time for dental technicians and 4) standardises the quality of restorations.[8][13]

Ceramic materials in particular, can be highly time-consuming to work with. To make a ceramic dental prosthesis by hand, the technician has to meticulously build up porcelain powder and sinter it onto the surface of a coping. With CAD/CAM, labour times are significantly reduced, with CAD systems with some reviews reporting that only 5–6 minutes of technician input is required to produce a dental prosthesis.[13] In this way, the cost of production is reduced because labour costs are lower. Furthermore, CAD/CAM systems mill prosthesis from blocks of material which are mass manufactured, again reducing costs for the dental offices and laboratories when compared with traditional techniques.[13] These blocks are made so that any internal porosities have been removed which are difficult to eliminate during conventional fabrication.[13]

CAD/CAM has also found great merit with regards to reducing the shrinkage which occurs when ceramics are heated during sintering – a process required to give the ceramic restoration adequate strength so it can be used successfully within the mouth. It is difficult to account for this phenomenon in a dental laboratory using traditional techniques.[13] CAM can reduce shrinkage by two different methods. The first is to produce a prosthesis just greater than the desired size. This means that on firing, the prosthesis will shrink to the original intended size.[13] The second is by milling the prosthesis from a block that has already been fully sintered, which eliminates shrinkage but causes increased wear on cutting tools because the block is stronger than when partially sintered.[13]

Benefits of intraoral scanning

[edit]The advent of intraoral scanners affords additional advantages when compared with the traditional physical workflow, particularly for dentists. In the traditional method, dental impressions must be taken, and the materials used to facilitate this are vulnerable to distortion over time which can decrease the accuracy of the eventual dental prosthesis. These inaccuracies are compounded by subsequent steps such as the fabrication of study models based on the impressions. Intra-oral scanners rapidly digitise what they scan which removes the risk of distortion/damage to the date.[25] Furthermore, dental impressions are often discomforting for patients, particularly those who have a strong gag reflex due to the bulk of material needed to capture a patient's entire dentition.[25] Intra-oral scanners reduce this element.

Intraoral scanning saves considerable time in post processing when compared with conventional dental impressions because the 3D model can be instantly emailed to a dental laboratory, whereas with the conventional technique, the impression must be disinfected and physically transported to the laboratory which is a longer process.[25]

Disadvantages of CAD/CAM

[edit]- Learning curve: With any new technology there is a steep learning curve. With time and experience operators will need to understand how to work the equipment and software used for CAD/CAM technology. Initially it can be difficult to adopt a new digital workflow when operators were comfortable with using their long-standing process in dentistry. This would also mean staff would need to be trained to feel comfortable using CAD/CAM systems.

- Cost: digital dentistry requires a large financial investment, including buying and maintaining equipment as well as software updates.[26] However, in the long run the investment will pay off as it can save money on expenses such as laboratory fees and single use impression equipment.[27]

- Errors in occlusion assessment: Compared to the conventional technique of making complete dentures, CAD/CAM has a few disadvantages.[28] The systems do not accurately assess element of balanced occlusion. As the denture teeth are not set on the denture base with the assistance of an articulator, there is difficulty in achieving a balanced occlusion. Hence, human assessment is still required, and the teeth will have to be clinically remounted to achieve balanced occlusion.[29]

- Environmental impact: resin particles are produced during the milling process, which adds to plastic pollution.[27]

Future prospects

[edit]Digital dentistry is growing at an accelerating rate, and CAD/CAM systems will continue to evolve and improve.[30][31]

References

[edit]- ^ Davidowitz G, Kotick PG. (2011), "The use of CAD/CAM in dentistry.", Dent Clin North Am, 55 (3): 559–570, doi:10.1016/j.cden.2011.02.011, PMID 21726690.

- ^ Rekow D (1987), "Computer-aided design and manufacturing in dentistry: a review of the state of the art", J Prosthet Dent, 58 (4): 512–516, doi:10.1016/0022-3913(87)90285-X, PMID 3312586.

- ^ Oen, Kay T; Veitz-Keenan, Analia; Spivakovsky, Silvia; Wong, Y Jo; Bakarman, Eman; Yip, Julie (April 9, 2014). "CAD/CAM versus traditional indirect methods in the fabrication of inlays, onlays, and crowns". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011063. ISSN 1465-1858.

- ^ Kastyl, Jaroslav; Chlup, Zdenek; Stastny, Premysl; Trunec, Martin (August 17, 2020). "Machinability and properties of zirconia ceramics prepared by gelcasting method". Advances in Applied Ceramics. 119 (5–6): 252–260. Bibcode:2020AdApC.119..252K. doi:10.1080/17436753.2019.1675402. hdl:11012/181089. ISSN 1743-6753. S2CID 210795876.

- ^ a b c d Edelhoff, D.; Schweiger, J.; Beuer, F. (May 2008). "Digital dentistry: an overview of recent developments for CAD/CAM generated restorations". British Dental Journal. 204 (9): 505–511. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.350. ISSN 1476-5373. PMID 18469768.

- ^ Dawood, A.; Marti, B. Marti; Sauret-Jackson, V.; Darwood, A. (December 11, 2015). "3D printing in dentistry". British Dental Journal. 219 (11): 521–529. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.914. ISSN 0007-0610. PMID 26657435. S2CID 2819140.

- ^ a b c Ahmed, Khaled E (June 2018). "We're Going Digital: The Current State of CAD/CAM Dentistry in Prosthodontics". Primary Dental Journal. 7 (2): 30–35. doi:10.1177/205016841800700205. ISSN 2050-1684. PMID 30095879. S2CID 51957826.

- ^ a b c Joda, Tim; Zarone, Fernando; Ferrari, Marco (December 2017). "The complete digital workflow in fixed prosthodontics: a systematic review". BMC Oral Health. 17 (1): 124. doi:10.1186/s12903-017-0415-0. ISSN 1472-6831. PMC 5606018. PMID 28927393.

- ^ Miyazaki, T.; Hotta, Y.; Kunii, J.; Kuriyama, S.; Tamaki, Y. (January 2009). "A review of dental CAD/CAM: current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience". Dental Materials Journal. 28 (1): 44–56. doi:10.4012/dmj.28.44. PMID 19280967.

- ^ "François Duret: Inventor of Dental CAD/CAM". Francois Duret. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ "Journal of the American Dental Association Article" (PDF). François Duret. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Miyazaki, T; Hotta, Y (June 2011). "CAD/CAM systems available for the fabrication of crown and bridge restorations: CAD/CAM systems". Australian Dental Journal. 56: 97–106. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01300.x. PMID 21564120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Miyazaki, Takashi; Hotta, Yasuhiro; Kunii, Jun; Kuriyama, Soichi; Tamaki, Yukimichi (2009). "A review of dental CAD/CAM: current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience". Dental Materials Journal. 28 (1): 44–56. doi:10.4012/dmj.28.44. ISSN 1881-1361. PMID 19280967.

- ^ Masek, R. (January 2005). "Margin isolation for optical impressions and adhesion". International Journal of Computer Dentistry. 8 (1): 69–76. PMID 15892526.

- ^ "CAD/CAM Technology: You Can't Afford NOT to Have It". Sidekick Magazine. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Oen, Kay T; Veitz-Keenan, Analia; Spivakovsky, Silvia; Wong, Y Jo; Bakarman, Eman; Yip, Julie (April 9, 2014). "CAD/CAM versus traditional indirect methods in the fabrication of inlays, onlays, and crowns". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011063. ISSN 1465-1858.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vecsei, Bálint; Czigola, Alexandra; Róth, Ivett; Hermann, Peter; Borbély, Judit (2021), Kinariwala, Niraj; Samaranayake, Lakshman (eds.), "Digital Impression Systems, CAD/CAM, and STL file", Guided Endodontics, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 27–63, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-55281-7_3, ISBN 978-3-030-55280-0, S2CID 229406286, retrieved March 11, 2022

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Chiu, Asher; Chen, Yen-Wei; Hayashi, Juri; Sadr, Alireza (February 20, 2020). "Accuracy of CAD/CAM Digital Impressions with Different Intraoral Scanner Parameters". Sensors. 20 (4): 1157. Bibcode:2020Senso..20.1157C. doi:10.3390/s20041157. ISSN 1424-8220. PMC 7071446. PMID 32093174.

- ^ Mangano, Francesco; Gandolfi, Andrea; Luongo, Giuseppe; Logozzo, Silvia (December 2017). "Intraoral scanners in dentistry: a review of the current literature". BMC Oral Health. 17 (1): 149. doi:10.1186/s12903-017-0442-x. ISSN 1472-6831. PMC 5727697. PMID 29233132.

- ^ a b Logozzo, Silvia; Zanetti, Elisabetta M.; Franceschini, Giordano; Kilpelä, Ari; Mäkynen, Anssi (March 2014). "Recent advances in dental optics – Part I: 3D intraoral scanners for restorative dentistry". Optics and Lasers in Engineering. 54: 203–221. Bibcode:2014OptLE..54..203L. doi:10.1016/j.optlaseng.2013.07.017.

- ^ a b c d Griggs, Jason A. (July 2007). "Recent Advances in Materials for All-Ceramic Restorations". Dental Clinics of North America. 51 (3): 713–727. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2007.04.006. PMC 2833171. PMID 17586152.

- ^ a b c Lambert, Hugo; Durand, Jean-Cédric; Jacquot, Bruno; Fages, Michel (2017). "Dental biomaterials for chairside CAD/CAM: State of the art". The Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics. 9 (6): 486–495. doi:10.4047/jap.2017.9.6.486. ISSN 2005-7806. PMC 5741454. PMID 29279770.

- ^ Oen, Kay T; Veitz-Keenan, Analia; Spivakovsky, Silvia; Wong, Y Jo; Bakarman, Eman; Yip, Julie (April 9, 2014). "CAD/CAM versus traditional indirect methods in the fabrication of inlays, onlays, and crowns". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011063. ISSN 1465-1858.

- ^ Payne, Alan GT; Alsabeeha, Nabeel HM; Atieh, Momen A; Esposito, Marco; Ma, Sunyoung; Anas El-Wegoud, Marwah (October 11, 2018). "Interventions for replacing missing teeth: attachment systems for implant overdentures in edentulous jaws". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10) CD008001. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008001.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6516946. PMID 30308116.

- ^ a b c Mangano, Francesco; Gandolfi, Andrea; Luongo, Giuseppe; Logozzo, Silvia (December 2017). "Intraoral scanners in dentistry: a review of the current literature". BMC Oral Health. 17 (1): 149. doi:10.1186/s12903-017-0442-x. ISSN 1472-6831. PMC 5727697. PMID 29233132.

- ^ Dawood, A.; Marti, B. Marti; Sauret-Jackson, V.; Darwood, A. (December 2015). "3D printing in dentistry". British Dental Journal. 219 (11): 521–529. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.914. ISSN 1476-5373. PMID 26657435. S2CID 2819140.

- ^ a b Baba, Nadim Z.; Goodacre, Brian J.; Goodacre, Charles J.; Müller, Frauke; Wagner, Stephen (May 2021). "CAD/CAM Complete Denture Systems and Physical Properties: A Review of the Literature". Journal of Prosthodontics. 30 (S2): 113–124. doi:10.1111/jopr.13243. ISSN 1059-941X. PMID 32844510. S2CID 221327373.

- ^ KANAZAWA, Manabu; INOKOSHI, Masanao; MINAKUCHI, Shunsuke; OHBAYASHI, Naoto (2011). "Trial of a CAD/CAM system for fabricating complete dentures". Dental Materials Journal. 30 (1): 93–96. doi:10.4012/dmj.2010-112. ISSN 1881-1361. PMID 21282882.

- ^ Bidra, Avinash S.; Taylor, Thomas D.; Agar, John R. (June 2013). "Computer-aided technology for fabricating complete dentures: Systematic review of historical background, current status, and future perspectives". The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 109 (6): 361–366. doi:10.1016/s0022-3913(13)60318-2. ISSN 0022-3913. PMID 23763779.

- ^ De Sousa Muianga, Mick Iván (2009). Data capture stabilizing device for the CEREC CAD/CAM chairside camera (Master of Science in Dentistry). Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- ^ Ahmed, Khaled E (June 2018). "We're Going Digital: The Current State of CAD/CAM Dentistry in Prosthodontics". Primary Dental Journal. 7 (2): 30–35. doi:10.1177/205016841800700205. ISSN 2050-1684. PMID 30095879. S2CID 51957826.