Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Software

View on Wikipedia

Software consists of computer programs that instruct the execution of a computer.[1] Software also includes design documents and specifications.

The history of software is closely tied to the development of digital computers in the mid-20th century. Early programs were written in the machine language specific to the hardware. The introduction of high-level programming languages in 1958 allowed for more human-readable instructions, making software development easier and more portable across different computer architectures. Software in a programming language is run through a compiler or interpreter to execute on the architecture's hardware. Over time, software has become complex, owing to developments in networking, operating systems, and databases.

Software can generally be categorized into two main types:

- operating systems, which manage hardware resources and provide services for applications

- application software, which performs specific tasks for users

The rise of cloud computing has introduced the new software delivery model Software as a Service (SaaS). In SaaS, applications are hosted by a provider and accessed over the Internet.

The process of developing software involves several stages. The stages include software design, programming, testing, release, and maintenance. Software quality assurance and security are critical aspects of software development, as bugs and security vulnerabilities can lead to system failures and security breaches. Additionally, legal issues such as software licenses and intellectual property rights play a significant role in the distribution of software products.

History

[edit]

The first use of the word software to describe computer programs is credited to mathematician John Wilder Tukey in 1958.[3][4] The first programmable computers, which appeared at the end of the 1940s,[5] were programmed in machine language. Machine language is difficult to debug and not portable across different computers.[6] Initially, hardware resources were more expensive than human resources.[7] As programs became complex, programmer productivity became the bottleneck. The introduction of high-level programming languages in 1958 hid the details of the hardware and expressed the underlying algorithms into the code .[8][9] Early languages include Fortran, Lisp, and COBOL.[9]

Types

[edit]

There are two main types of software:

- Operating systems are "the layer of software that manages a computer's resources for its users and their applications".[10] There are three main purposes that an operating system fulfills:[11]

- Allocating resources between different applications, deciding when they will receive central processing unit (CPU) time or space in memory.[11]

- Providing an interface that abstracts the details of accessing hardware details (like physical memory) to make things easier for programmers.[11][12]

- Offering common services, such as an interface for accessing network and disk devices. This enables an application to be run on different hardware without needing to be rewritten.[13]

- Application software runs on top of the operating system and uses the computer's resources to perform a task.[14] There are many different types of application software because the range of tasks that can be performed with modern computers is so large.[15] Applications account for most software[16] and require the environment provided by an operating system, and often other applications, in order to function.[17]

Software can also be categorized by how it is deployed. Traditional applications are purchased with a perpetual license for a specific version of the software, downloaded, and run on hardware belonging to the purchaser.[18] The rise of the Internet and cloud computing enabled a new model, software as a service (SaaS),[19] in which the provider hosts the software (usually built on top of rented infrastructure or platforms)[20] and provides the use of the software to customers, often in exchange for a subscription fee.[18] By 2023, SaaS products—which are usually delivered via a web application—had become the primary method that companies deliver applications.[21]

Software development and maintenance

[edit]

Software companies aim to deliver a high-quality product on time and under budget. A challenge is that software development effort estimation is often inaccurate.[22] Software development begins by conceiving the project, evaluating its feasibility, analyzing the business requirements, and making a software design.[23][24] Most software projects speed up their development by reusing or incorporating existing software, either in the form of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) or open-source software.[25][26] Software quality assurance is typically a combination of manual code review by other engineers[27] and automated software testing. Due to time constraints, testing cannot cover all aspects of the software's intended functionality, so developers often focus on the most critical functionality.[28] Formal methods are used in some safety-critical systems to prove the correctness of code,[29] while user acceptance testing helps to ensure that the product meets customer expectations.[30] There are a variety of software development methodologies, which vary from completing all steps in order to concurrent and iterative models.[31] Software development is driven by requirements taken from prospective users, as opposed to maintenance, which is driven by events such as a change request.[32]

Frequently, software is released in an incomplete state when the development team runs out of time or funding.[33] Despite testing and quality assurance, virtually all software contains bugs where the system does not work as intended. Post-release software maintenance is necessary to remediate these bugs when they are found and keep the software working as the environment changes over time.[34] New features are often added after the release. Over time, the level of maintenance becomes increasingly restricted before being cut off entirely when the product is withdrawn from the market.[35] As software ages, it becomes known as legacy software and can remain in use for decades, even if there is no one left who knows how to fix it.[36] Over the lifetime of the product, software maintenance is estimated to comprise 75 percent or more of the total development cost.[37][38]

Completing a software project involves various forms of expertise, not just in software programmers but also testing, documentation writing, project management, graphic design, user experience, user support, marketing, and fundraising.[39][40][24]

Quality and security

[edit]Software quality is defined as meeting the stated requirements as well as customer expectations.[41] Quality is an overarching term that can refer to a code's correct and efficient behavior, its reusability and portability, or the ease of modification.[42] It is usually more cost-effective to build quality into the product from the beginning rather than try to add it later in the development process.[43] Higher quality code will reduce lifetime cost to both suppliers and customers as it is more reliable and easier to maintain.[44][45] Software failures in safety-critical systems can be very serious including death.[44] By some estimates, the cost of poor quality software can be as high as 20 to 40 percent of sales.[46] Despite developers' goal of delivering a product that works entirely as intended, virtually all software contains bugs.[47]

The rise of the Internet also greatly increased the need for computer security as it enabled malicious actors to conduct cyberattacks remotely.[48][49] If a bug creates a security risk, it is called a vulnerability.[50][51] Software patches are often released to fix identified vulnerabilities, but those that remain unknown (zero days) as well as those that have not been patched are still liable for exploitation.[52] Vulnerabilities vary in their ability to be exploited by malicious actors,[50] and the actual risk is dependent on the nature of the vulnerability as well as the value of the surrounding system.[53] Although some vulnerabilities can only be used for denial of service attacks that compromise a system's availability, others allow the attacker to inject and run their own code (called malware), without the user being aware of it.[50] To thwart cyberattacks, all software in the system must be designed to withstand and recover from external attack.[49] Despite efforts to ensure security, a significant fraction of computers are infected with malware.[54]

Encoding and execution

[edit]Programming languages

[edit]

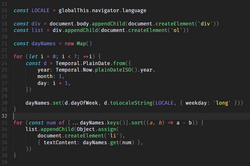

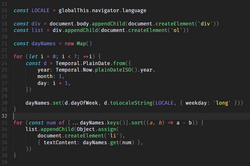

Programming languages are the format in which software is written. Since the 1950s, thousands of different programming languages have been invented; some have been in use for decades, while others have fallen into disuse.[55] Some definitions classify machine code—the exact instructions directly implemented by the hardware—and assembly language—a more human-readable alternative to machine code whose statements can be translated one-to-one into machine code—as programming languages.[56] Programs written in the high-level programming languages used to create software share a few main characteristics: knowledge of machine code is not necessary to write them, they can be ported to other computer systems, and they are more concise and human-readable than machine code.[57] They must be both human-readable and capable of being translated into unambiguous instructions for computer hardware.[58]

Compilation, interpretation, and execution

[edit]The invention of high-level programming languages was simultaneous with the compilers needed to translate them automatically into machine code.[59] Most programs do not contain all the resources needed to run them and rely on external libraries. Part of the compiler's function is to link these files in such a way that the program can be executed by the hardware. Once compiled, the program can be saved as an object file and the loader (part of the operating system) can take this saved file and execute it as a process on the computer hardware.[60] Some programming languages use an interpreter instead of a compiler. An interpreter converts the program into machine code at run time, which makes them 10 to 100 times slower than compiled programming languages.[61][62]

Legal issues

[edit]Liability

[edit]Software is often released with the knowledge that it is incomplete or contains bugs.[citation needed] Purchasers knowingly buy it in this state,[citation needed] which has led to a legal regime where liability for software products is significantly curtailed compared to other products.[63]

Licenses

[edit]

Since the mid-1970s, software and its source code have been protected by copyright law that vests the owner with the exclusive right to copy the code. The underlying ideas or algorithms are not protected by copyright law, but are sometimes treated as a trade secret and concealed by such methods as non-disclosure agreements.[64] A software copyright is often owned by the person or company that financed or made the software (depending on their contracts with employees or contractors who helped to write it).[65] Some software is in the public domain and has no restrictions on who can use it, copy or share it, or modify it; a notable example is software written by the United States Government.[citation needed] Free and open-source software also allow free use, sharing, and modification, perhaps with a few specified conditions.[65] The use of some software is governed by an agreement (software license) written by the copyright holder and imposed on the user. Proprietary software is usually sold under a restrictive license that limits its use and sharing.[66] Some free software licenses require that modified versions must be released under the same license, which prevents the software from being sold or distributed under proprietary restrictions.[67]

Patents

[edit]Patents give an inventor an exclusive, time-limited license for a novel product or process.[68] Ideas about what software could accomplish are not protected by law and concrete implementations are instead covered by copyright law. In some countries, a requirement for the claimed invention to have an effect on the physical world may also be part of the requirements for a software patent to be held valid.[69] Software patents have been historically controversial. Before the 1998 case State Street Bank & Trust Co. v. Signature Financial Group, Inc., software patents were generally not recognized in the United States. In that case, the Supreme Court decided that business processes could be patented.[70] Patent applications are complex and costly, and lawsuits involving patents can drive up the cost of products.[71] Unlike copyrights, patents generally only apply in the jurisdiction where they were issued.[72]

Impact

[edit]

Engineer Capers Jones writes that "computers and software are making profound changes to every aspect of human life: education, work, warfare, entertainment, medicine, law, and everything else".[74] It has become ubiquitous in everyday life in developed countries.[75] In many cases, software augments the functionality of existing technologies such as household appliances and elevators.[76] Software also spawned entirely new technologies such as the Internet, video games, mobile phones, and GPS.[76][77] New methods of communication, including email, forums, blogs, microblogging, wikis, and social media, were enabled by the Internet.[78] Massive amounts of knowledge exceeding any paper-based library are now available with a quick web search.[77] Most creative professionals have switched to software-based tools such as computer-aided design, 3D modeling, digital image editing, and computer animation.[73] Almost every complex device is controlled by software.[77]

References

[edit]- ^ Stair, Ralph M. (2003). Principles of Information Systems, Sixth Edition. Thomson. p. 16. ISBN 0-619-06489-7.

Software consists of computer programs that govern the operation of the computer.

- ^ Jones 2014, pp. 19, 22.

- ^ Tracy 2021, p. 2.

- ^ "software (n.), sense 2.a". Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2024. doi:10.1093/OED/3803978366. Retrieved 15 July 2025.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 519.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 522.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 521.

- ^ a b Tracy 2021, p. 1.

- ^ Anderson & Dahlin 2014, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Anderson & Dahlin 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Tanenbaum & Bos 2023, p. 5.

- ^ Anderson & Dahlin 2014, pp. 7, 9, 13.

- ^ Anderson & Dahlin 2014, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 121.

- ^ Tracy 2021, p. 66.

- ^ Tracy 2021, p. 72.

- ^ a b O'Regan 2022, p. 386.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly & Garcia-Swartz 2015, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Rosati & Lynn 2020, p. 23.

- ^ Watt 2023, p. 4.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 7.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 5.

- ^ a b Dooley 2017, p. 1.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, pp. 18, 110–111.

- ^ Tracy 2021, pp. 43, 76.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, pp. 117–118.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 54.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 267.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 20.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 9.

- ^ Tripathy & Naik 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Reifer 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Tripathy & Naik 2014, pp. 4, 27.

- ^ Tripathy & Naik 2014, p. 89.

- ^ Tracy 2021, p. 3.

- ^ Varga 2018, p. 6.

- ^ Ulziit et al. 2015, p. 764.

- ^ Tucker, Morelli & de Silva 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Stull 2018, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Galin 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Galin 2018, p. 26.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, pp. 68, 117.

- ^ a b O'Regan 2022, pp. 3, 268.

- ^ Varga 2018, p. 12.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 119.

- ^ Ablon & Bogart 2017, p. 1.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly & Garcia-Swartz 2015, p. 164.

- ^ a b O'Regan 2022, p. 266.

- ^ a b c Ablon & Bogart 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 25.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Haber & Hibbert 2018, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Kitchin & Dodge 2011, p. 37.

- ^ Tracy 2021, p. 117.

- ^ Tracy 2021, pp. 118–120.

- ^ Tracy 2021, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Kitchin & Dodge 2011, p. 26.

- ^ Tracy 2021, p. 121.

- ^ Tracy 2021, pp. 122–123.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 375.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 28.

- ^ Kitchin & Dodge 2011, pp. 36–37.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, pp. 394–396.

- ^ a b O'Regan 2022, p. 403.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, pp. 394, 404.

- ^ Langer 2016, pp. 44–45.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 395.

- ^ Gerardo Con Díaz, "The Text in the Machine: American Copyright Law and the Many Natures of Software, 1974–1978", Technology and Culture 57 (October 2016), 753–79.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 19.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 398.

- ^ O'Regan 2022, p. 399.

- ^ a b Manovich 2013, p. 333.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Kitchin & Dodge 2011, p. iv.

- ^ a b Kitchin & Dodge 2011, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Jones 2014, p. xxviii.

- ^ Manovich 2013, p. 329.

Sources

[edit]- Ablon, Lillian; Bogart, Andy (2017). Zero Days, Thousands of Nights: The Life and Times of Zero-Day Vulnerabilities and Their Exploits (PDF). Rand Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-9761-3.

- Anderson, Thomas; Dahlin, Michael (2014). Operating Systems: Principles and Practice (2 ed.). Recursive Books. ISBN 978-0-9856735-2-9.

- Campbell-Kelly, Martin; Garcia-Swartz, Daniel D. (2015). From Mainframes to Smartphones: A History of the International Computer Industry. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-28655-9.

- Daswani, Neil; Elbayadi, Moudy (2021). Big Breaches: Cybersecurity Lessons for Everyone. Apress. ISBN 978-1-4842-6654-0.

- Dooley, John F. (2017). Software Development, Design and Coding: With Patterns, Debugging, Unit Testing, and Refactoring. Apress. ISBN 978-1-4842-3153-1.

- Gabbrielli, Maurizio; Martini, Simone (2023). Programming Languages: Principles and Paradigms (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-031-34144-1.

- Galin, Daniel (2018). Software Quality: Concepts and Practice. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-13449-7.

- Haber, Morey J.; Hibbert, Brad (2018). Asset Attack Vectors: Building Effective Vulnerability Management Strategies to Protect Organizations. Apress. ISBN 978-1-4842-3627-7.

- Jones, Capers (2014). The Technical and Social History of Software Engineering. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-321-90342-6.

- Kitchin, Rob; Dodge, Martin (2011). Code/space: Software and Everyday Life. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04248-2.

- Langer, Arthur M. (2016). Guide to Software Development: Designing and Managing the Life Cycle. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4471-6799-0.

- Manovich, Lev (2013). Software Takes Command. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-62356-745-3.

- O'Regan, Gerard (2022). Concise Guide to Software Engineering: From Fundamentals to Application Methods. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-031-07816-3.

- Osterweil, Leon J. (2013). "What Is Software? The Role of Empirical Methods in Answering the Question". Perspectives on the Future of Software Engineering: Essays in Honor of Dieter Rombach. Springer. pp. 237–254. ISBN 978-3-642-37395-4.

- Rahman, Hanif Ur; da Silva, Alberto Rodrigues; Alzayed, Asaad; Raza, Mushtaq (2024). "A Systematic Literature Review on Software Maintenance Offshoring Decisions". Information and Software Technology. 172 107475. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2024.107475.

- Reifer, Donald J. (2012). Software Maintenance Success Recipes. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-5167-8.

- Rosati, Pierangelo; Lynn, Theo (2020). "Measuring the Business Value of Infrastructure Migration to the Cloud". Measuring the Business Value of Cloud Computing. Springer International Publishing. pp. 19–37. ISBN 978-3-030-43198-3.

- Sebesta, Robert W. (2012). Concepts of Programming Languages (10 ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-13-139531-2.

- Stull, Edward (2018). UX Fundamentals for Non-UX Professionals: User Experience Principles for Managers, Writers, Designers, and Developers. Apress. ISBN 978-1-4842-3811-0.

- Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Bos, Herbert (2023). Modern Operating Systems, Global Edition. Pearson Higher Ed. ISBN 978-1-292-72789-9.

- Tracy, Kim W. (2021). Software: A Technical History. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4503-8724-8.

- Tripathy, Priyadarshi; Naik, Kshirasagar (2014). Software Evolution and Maintenance: A Practitioner's Approach. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-60341-3.

- Tucker, Allen; Morelli, Ralph; de Silva, Chamindra (2011). Software Development: An Open Source Approach. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-8460-7.

- Ulziit, Bayarbuyan; Warraich, Zeeshan Akhtar; Gencel, Cigdem; Petersen, Kai (2015). "A conceptual framework of challenges and solutions for managing global software maintenance". Journal of Software: Evolution and Process. 27 (10): 763–792. doi:10.1002/smr.1720.

- Watt, Andy (2023). Building Modern SaaS Applications with C# And . NET: Build, Deploy, and Maintain Professional SaaS Applications. Packt. ISBN 978-1-80461-087-9.

- Varga, Ervin (2018). Unraveling Software Maintenance and Evolution: Thinking Outside the Box. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-71303-8.

Software

View on GrokipediaHistory

The term "software" emerged in the late 1950s as a counterpart to "hardware," initially used informally to describe the instructions directing computer operations, with formal adoption around 1958–1960. Early computing relied on machine code—binary instructions directly executable by hardware—and assembly languages that used mnemonic codes for human readability, translated via assemblers. The development of higher-level programming languages marked a significant evolution: FORTRAN, introduced in 1957 by IBM for scientific and engineering computations, allowed algebraic notation closer to mathematical expressions; COBOL, standardized in 1959, facilitated business data processing with English-like syntax. These advancements shifted programming from low-level hardware-specific instructions to abstracted, portable code, enabling broader application development amid the growth of mainframe computers in the 1960s.[1]Types

Software is broadly classified into system software, application software, and network software. System software includes operating systems, device drivers, and utility programs that manage hardware resources and provide essential services to the computer, enabling other software to run efficiently. Examples include Microsoft Windows, Unix-like systems such as Linux, and utilities like disk defragmenters.[1] Application software performs specific tasks for end-users, such as word processing, data analysis, or entertainment; common examples are Microsoft Office suite for productivity and web browsers like Google Chrome.[1] Network software encompasses protocols, middleware, and tools that facilitate communication and data exchange between networked devices, including TCP/IP stacks and distributed application frameworks.[1]Software development and maintenance

Software development is the process of designing, coding, testing, documenting, and maintaining applications, frameworks, or other software components. It encompasses activities from initial conception through to ongoing support after deployment. The process is typically structured around the software development life cycle (SDLC), which provides a systematic framework for producing high-quality software efficiently and with minimized risks.[2] The SDLC generally includes the following phases:- Planning: Defining project goals, scope, feasibility, resource requirements, and scheduling.

- Requirements analysis: Gathering, analyzing, and documenting user needs and functional/non-functional requirements.

- Design: Creating architectural and detailed designs, including system structure, interfaces, and data models.

- Implementation: Writing code and constructing the software product.

- Testing: Verifying the software against requirements through unit, integration, system, and acceptance testing to identify and fix defects.

- Deployment: Releasing the software into the production environment for use.

- Maintenance: Performing post-delivery modifications to address issues, adapt to changes, improve attributes, or prevent problems.

- Corrective maintenance: Fixes defects or faults to restore the software to its specified functionality.

- Adaptive maintenance: Modifies the software to accommodate changes in the operational environment, such as new hardware, operating systems, or regulations.

- Perfective maintenance: Enhances performance, maintainability, usability, or other qualities without altering primary functions.

- Preventive maintenance: Proactively modifies the software to prevent potential future problems, such as by refactoring code or addressing latent vulnerabilities.

Quality and security

Software quality refers to the degree to which a software product satisfies stated and implied needs under specified conditions, encompassing both the product and the development processes used to create it. Key characteristics include functional suitability, performance efficiency, compatibility, usability, reliability, security, maintainability, and portability, as defined in ISO/IEC 25010. These attributes are assessed through standards such as ISO 5055, which measures structural quality during development by identifying weaknesses in security, reliability, performance efficiency, and maintainability to prevent operational failures and reduce costs.[5][6] Security issues in software arise from vulnerabilities that can be exploited to compromise systems. Zero-day vulnerabilities, which are undisclosed flaws exploited before developers can patch them, pose significant risks. Empirical analysis of 200 real-world zero-day vulnerabilities reveals an average lifespan of 6.9 years from discovery to public disclosure or end-of-life, with only 25% surviving beyond 1.51 years or lasting longer than 9.5 years. The median time to develop a functional exploit after identifying an exploitable vulnerability is 22 days. Approximately 5.7% of stockpiled zero-days are publicly discovered by others within a year. Effective management involves timely patching, secure development practices, and considering vulnerabilities as "alive" (undisclosed), "dead" (patched), or "quasi-alive" (exploitable in legacy versions), highlighting the need for ongoing vigilance and disclosure strategies.[7]Encoding and execution

Software encoding involves representing instructions in forms executable by computer hardware, ranging from binary machine code to higher-level abstractions translated via specialized processes. Execution occurs when these instructions are loaded into memory and processed by the processor.Programming languages

Programming languages enable the specification of algorithms and instructions for computers. They are categorized by abstraction level from hardware. Machine language consists of binary numeric codes (0s and 1s) directly interpretable by the processor, specific to each architecture and challenging for humans to compose due to its lack of readability.[1] Assembly language, a low-level step above, employs mnemonic codes (e.g., "ADD") and symbolic addresses, facilitating hardware-specific programming like device drivers while remaining translatable to machine code via assemblers.[1] Higher-level languages abstract hardware details, using syntax akin to natural or mathematical language for broader applicability. FORTRAN, developed in 1957 for scientific computing, supports arrays, loops, and subroutines, optimizing for numerical efficiency. COBOL, introduced in 1959, adopts English-like syntax for business data processing, incorporating record structures for heterogeneous data. ALGOL (1958–1960) emphasizes algorithmic expression, introducing block structures and recursion, influencing subsequent languages.[1]Compilation, interpretation, and execution

Higher-level languages are translated to machine code through compilation or interpretation. Compilation involves a compiler converting the entire source code into executable machine instructions prior to runtime, producing efficient, architecture-specific binaries as in FORTRAN's design for optimized output.[1] Interpretation executes code line-by-line via an interpreter without full pre-translation, enabling flexibility but potentially at performance cost, contrasting compilation's upfront processing. Assembly code undergoes straightforward substitution to machine language. Once encoded, programs reside in storage (e.g., disk) and execute by loading into RAM, where the processor fetches, decodes, and performs instructions sequentially.[1]Legal issues

Liability

Software liability refers to the legal responsibility of software developers, manufacturers, vendors, or distributors for damages caused by defects, failures, or vulnerabilities in their software. Liability can arise under several legal theories:- Strict liability — applies when software is treated as a product, holding the producer liable for harm caused by unreasonably dangerous defects without requiring proof of fault.

- Negligence — holds parties liable for failing to exercise reasonable care in design, development, testing, or maintenance, leading to foreseeable harm.

- Breach of warranty or contract — arises from failure to meet express or implied assurances about the software's performance or fitness.