Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sintering

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2022) |

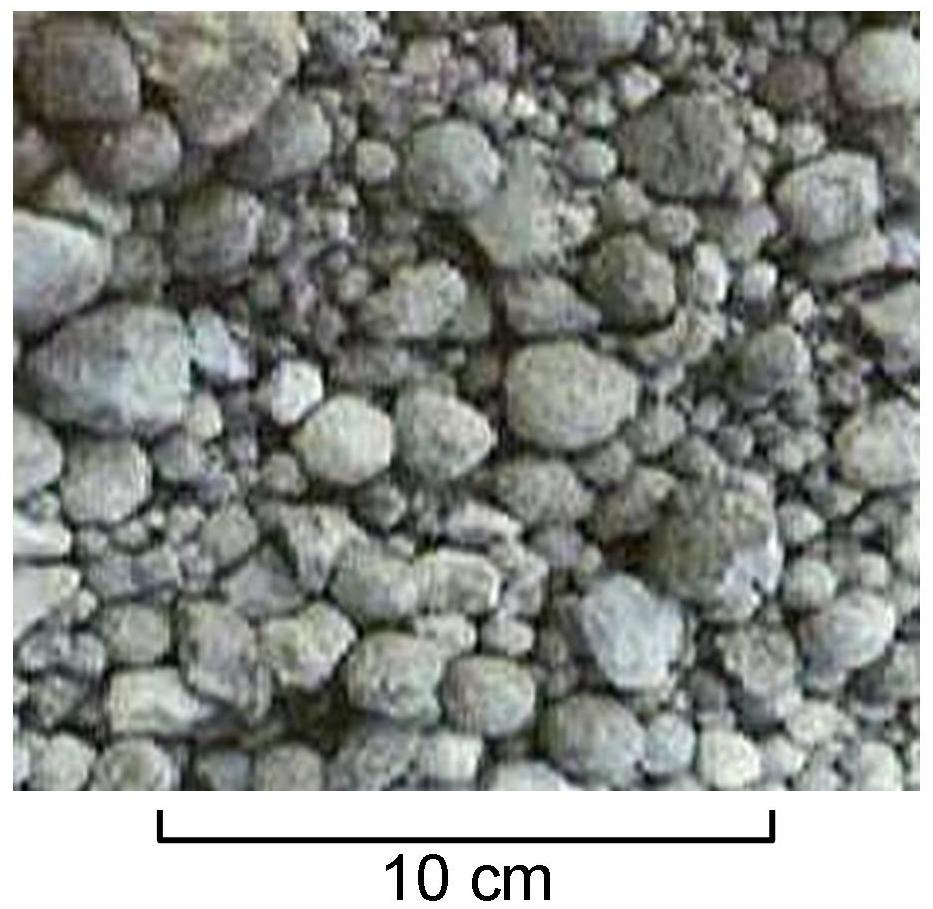

Sintering or frittage is the process of compacting and forming a solid mass of material by pressure[1] or heat[2] without melting it to the point of liquefaction. Sintering happens as part of a manufacturing process used with metals, ceramics, plastics, and other materials. The atoms/molecules in the sintered material diffuse across the boundaries of the particles, fusing the particles together and creating a solid piece.

Since the sintering temperature does not have to reach the melting point of the material, sintering is often chosen as the shaping process for materials with extremely high melting points, such as tungsten and molybdenum. The study of sintering in metallurgical powder-related processes is known as powder metallurgy.

An example of sintering can be observed when ice cubes in a glass of water adhere to each other, which is driven by the temperature difference between the water and the ice. Examples of pressure-driven sintering are the compacting of snowfall to a glacier, or the formation of a hard snowball by pressing loose snow together.

The material produced by sintering is called sinter. The word sinter comes from the Middle High German sinter, a cognate of English cinder.

General sintering

[edit]

Sintering is generally considered successful when the process reduces porosity and enhances properties such as strength, electrical conductivity, translucency and thermal conductivity. In some special cases, sintering is carefully applied to enhance the strength of a material while preserving porosity (e.g. in filters or catalysts, where gas adsorption is a priority). During the sintering process, atomic diffusion drives powder surface elimination in different stages, starting at the formation of necks between powders to final elimination of small pores at the end of the process.

The driving force for densification is the change in free energy from the decrease in surface area and lowering of the surface free energy by the replacement of solid-vapor interfaces. It forms new but lower-energy solid-solid interfaces with a net decrease in total free energy. On a microscopic scale, material transfer is affected by the change in pressure and differences in free energy across the curved surface. If the size of the particle is small (and its curvature is high), these effects become very large in magnitude. The change in energy is much higher when the radius of curvature is less than a few micrometers, which is one of the main reasons why much ceramic technology is based on the use of fine-particle materials.[3]

The ratio of bond area to particle size is a determining factor for properties such as strength and electrical conductivity. To yield the desired bond area, temperature and initial grain size are precisely controlled over the sintering process. At steady state, the particle radius and the vapor pressure are proportional to (p0)2/3 and to (p0)1/3, respectively.[3]

The source of power for solid-state processes is the change in free or chemical potential energy between the neck and the surface of the particle. This energy creates a transfer of material through the fastest means possible; if transfer were to take place from the particle volume or the grain boundary between particles, particle count would decrease and pores would be destroyed. Pore elimination is fastest in samples with many pores of uniform size because the boundary diffusion distance is smallest. During the latter portions of the process, boundary and lattice diffusion from the boundary become important.[3]

Control of temperature is very important to the sintering process, since grain-boundary diffusion and volume diffusion rely heavily upon temperature, particle size, particle distribution, material composition, and often other properties of the sintering environment itself.[3]

Ceramic sintering

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Sintering is part of the firing process used in the manufacture of pottery and other ceramic objects. Sintering and vitrification (which requires higher temperatures) are the two main mechanisms behind the strength and stability of ceramics. Sintered ceramic objects are made from substances such as glass, alumina, zirconia, silica, magnesia, lime, beryllium oxide, and ferric oxide. Some ceramic raw materials have a lower affinity for water and a lower plasticity index than clay, requiring organic additives in the stages before sintering.

Sintering begins when sufficient temperatures have been reached to mobilize the active elements in the ceramic material, which can start below their melting point (typically at 50–80% of their melting point[4]), e.g. as premelting. When sufficient sintering has taken place, the ceramic body will no longer break down in water; additional sintering can reduce the porosity of the ceramic, increase the bond area between ceramic particles, and increase the material strength.[5]

Industrial procedures to create ceramic objects via sintering of powders generally include:[6]

- mixing water, binder, deflocculant, and unfired ceramic powder to form a slurry

- spray-drying the slurry

- putting the spray dried powder into a mold and pressing it to form a green body (an unsintered ceramic item)

- heating the green body at low temperature to burn off the binder

- sintering at a high temperature to fuse the ceramic particles together.

All the characteristic temperatures associated with phase transformation, glass transitions, and melting points, occurring during a sinterisation cycle of a particular ceramic's formulation (i.e., tails and frits) can be easily obtained by observing the expansion-temperature curves during optical dilatometer thermal analysis. In fact, sinterisation is associated with a remarkable shrinkage of the material because glass phases flow once their transition temperature is reached, and start consolidating the powdery structure and considerably reducing the porosity of the material.

Sintering is performed at high temperature. Additionally, a second and/or third external force (such as pressure, electric current) could be used. A commonly used second external force is pressure. Sintering performed by only heating is generally termed "pressureless sintering", which is possible with graded metal-ceramic composites, utilising a nanoparticle sintering aid and bulk molding technology. A variant used for 3D shapes is called hot isostatic pressing.

To allow efficient stacking of product in the furnace during sintering and to prevent parts sticking together, many manufacturers separate ware using ceramic powder separator sheets. These sheets are available in various materials such as alumina, zirconia and magnesia. They are additionally categorized by fine, medium and coarse particle sizes. By matching the material and particle size to the ware being sintered, surface damage and contamination can be reduced while maximizing furnace loading.

Sintering of metallic powders

[edit]

Most metals can be sintered, although some with greater difficulty (i.e., aluminium alloy and titanium alloys[7]). This applies especially to pure metals produced in vacuum which suffer no surface contamination. Sintering under atmospheric pressure requires the use of a protective gas, quite often endothermic gas. Sintering, with subsequent reworking, can produce a great range of material properties. Changes in density, alloying, and heat treatments can alter the physical characteristics of various products. For instance, the Young's modulus En of sintered iron powders remains somewhat insensitive to sintering time, alloying, or particle size in the original powder for lower sintering temperatures, but depends upon the density of the final product:

where D is the density, E is Young's modulus and d is the maximum density of iron.

Sintering is static when a metal powder under certain external conditions may exhibit coalescence, and yet reverts to its normal behavior when such conditions are removed. In most cases, the density of a collection of grains increases as material flows into voids, causing a decrease in overall volume. Mass movements that occur during sintering consist of the reduction of total porosity by repacking, followed by material transport due to evaporation and condensation from diffusion. In the final stages, metal atoms move along crystal boundaries to the walls of internal pores, redistributing mass from the internal bulk of the object and smoothing pore walls. Surface tension is the driving force for this movement.

A special form of sintering (which is still considered part of powder metallurgy) is liquid-state sintering in which at least one but not all elements are in a liquid state. Liquid-state sintering is required for making cemented carbide and tungsten carbide.

Sintered bronze in particular is frequently used as a material for bearings, since its porosity allows lubricants to flow through it or remain captured within it. Sintered copper may be used as a wicking structure in certain types of heat pipe construction, where the porosity allows a liquid agent to move through the porous material via capillary action. For materials that have high melting points such as molybdenum, tungsten, rhenium, tantalum, osmium and carbon, sintering is one of the few viable manufacturing processes. In these cases, very low porosity is desirable and can often be achieved.

Sintered metal powder is used to make frangible shotgun shells called breaching rounds, as used by military and SWAT teams to quickly force entry into a locked room. These shotgun shells are designed to destroy door deadbolts, locks and hinges without risking lives by ricocheting or by flying on at lethal speed through the door. They work by destroying the object they hit and then dispersing into a relatively harmless powder.

Sintered bronze and stainless steel are used as filter materials in applications requiring high temperature resistance while retaining the ability to regenerate the filter element. For example, sintered stainless steel elements are employed for filtering steam in food and pharmaceutical applications, and sintered bronze in aircraft hydraulic systems.

Sintering of powders containing precious metals such as silver and gold is used to make small jewelry items. Evaporative self-assembly of colloidal silver nanocubes into supercrystals has been shown to allow the sintering of electrical joints at temperatures lower than 200 °C.[8]

Advantages

[edit]Particular advantages of the powder technology include:

- Very high levels of purity and uniformity in starting materials

- Preservation of purity, due to the simpler subsequent fabrication process (fewer steps) that it makes possible

- Stabilization of the details of repetitive operations, by control of grain size during the input stages

- Absence of binding contact between segregated powder particles – or "inclusions" (called stringering) – as often occurs in melting processes

- No deformation needed to produce directional elongation of grains

- Capability to produce materials of controlled, uniform porosity.

- Capability to produce nearly net-shaped objects.

- Capability to produce materials which cannot be produced by any other technology.

- Capability to fabricate high-strength material like turbine blades.

- After sintering the mechanical strength to handling becomes higher.

The literature contains many references on sintering dissimilar materials to produce solid/solid-phase compounds or solid/melt mixtures at the processing stage. Almost any substance can be obtained in powder form, through either chemical, mechanical or physical processes, so basically any material can be obtained through sintering. When pure elements are sintered, the leftover powder is still pure, so it can be recycled.

Disadvantages

[edit]Particular disadvantages of the powder technology include:[original research?]

- Sintering cannot create uniform sizes.

- Micro- and nanostructures produced before sintering are often destroyed.

Plastics sintering

[edit]Plastic materials are formed by sintering for applications that require materials of specific porosity. Sintered plastic porous components are used in filtration and to control fluid and gas flows. Sintered plastics are used in applications requiring caustic fluid separation processes such as the nibs in whiteboard markers, inhaler filters, and vents for caps and liners on packaging materials.[9] Sintered ultra high molecular weight polyethylene materials are used as ski and snowboard base materials. The porous texture allows wax to be retained within the structure of the base material, thus providing a more durable wax coating.

Liquid phase sintering

[edit]For materials that are difficult to sinter, a process called liquid phase sintering is commonly used. Materials for which liquid phase sintering is common are Si3N4, WC, SiC, and more. Liquid phase sintering is the process of adding an additive to the powder which will melt before the matrix phase. The process of liquid phase sintering has three stages:

- rearrangement – As the liquid melts capillary action will pull the liquid into pores and also cause grains to rearrange into a more favorable packing arrangement.

- solution-precipitation – In areas where capillary pressures are high (particles are close together) atoms will preferentially go into solution and then precipitate in areas of lower chemical potential where particles are not close or in contact. This is called contact flattening. This densifies the system in a way similar to grain boundary diffusion in solid state sintering. Ostwald ripening will also occur where smaller particles will go into solution preferentially and precipitate on larger particles leading to densification.

- final densification – densification of solid skeletal network, liquid movement from efficiently packed regions into pores.

For liquid phase sintering to be practical the major phase should be at least slightly soluble in the liquid phase and the additive should melt before any major sintering of the solid particulate network occurs, otherwise rearrangement of grains will not occur. Liquid phase sintering was successfully applied to improve grain growth of thin semiconductor layers from nanoparticle precursor films.[10]

Electric current assisted sintering

[edit]These techniques employ electric currents to drive or enhance sintering.[11][12] English engineer A. G. Bloxam registered in 1906 the first patent on sintering powders using direct current in vacuum. The primary purpose of his inventions was the industrial scale production of filaments for incandescent lamps by compacting tungsten or molybdenum particles. The applied current was particularly effective in reducing surface oxides that increased the emissivity of the filaments.[13]

In 1913, Weintraub and Rush patented a modified sintering method which combined electric current with pressure. The benefits of this method were proved for the sintering of refractory metals as well as conductive carbide or nitride powders. The starting boron–carbon or silicon–carbon powders were placed in an electrically insulating tube and compressed by two rods which also served as electrodes for the current. The estimated sintering temperature was 2000 °C.[13]

In the United States, sintering was first patented by Duval d'Adrian in 1922. His three-step process aimed at producing heat-resistant blocks from such oxide materials as zirconia, thoria or tantalia. The steps were: (i) molding the powder; (ii) annealing it at about 2500 °C to make it conducting; (iii) applying current-pressure sintering as in the method by Weintraub and Rush.[13]

Sintering that uses an arc produced via a capacitance discharge to eliminate oxides before direct current heating, was patented by G. F. Taylor in 1932. This originated sintering methods employing pulsed or alternating current, eventually superimposed to a direct current. Those techniques have been developed over many decades and summarized in more than 640 patents.[13]

Of these technologies the most well known is resistance sintering (also called hot pressing) and spark plasma sintering, while electro sinter forging is the latest advancement in this field.

Spark plasma sintering

[edit]In spark plasma sintering (SPS), external pressure and an electric field are applied simultaneously to enhance the densification of the metallic/ceramic powder compacts. However, after commercialization it was determined there is no plasma, so the proper name is spark sintering as coined by Lenel. The electric field driven densification supplements sintering with a form of hot pressing, to enable lower temperatures and taking less time than typical sintering.[14] For a number of years, it was speculated that the existence of sparks or plasma between particles could aid sintering; however, Hulbert and coworkers systematically proved that the electric parameters used during spark plasma sintering make it (highly) unlikely.[15] In light of this, the name "spark plasma sintering" has been rendered obsolete. Terms such as field assisted sintering technique (FAST), electric field assisted sintering (EFAS), and direct current sintering (DCS) have been implemented by the sintering community.[16] Using a direct current (DC) pulse as the electric current, spark plasma, spark impact pressure, joule heating, and an electrical field diffusion effect would be created.[17] By modifying the graphite die design and its assembly, it is possible to perform pressureless sintering in spark plasma sintering facility. This modified die design setup is reported to synergize the advantages of both conventional pressureless sintering and spark plasma sintering techniques.[18]

Electro sinter forging

[edit]Electro sinter forging is an electric current assisted sintering (ECAS) technology originated from capacitor discharge sintering. It is used for the production of diamond metal matrix composites and is under evaluation for the production of hard metals,[19] nitinol[20] and other metals and intermetallics. It is characterized by a very low sintering time, allowing machines to sinter at the same speed as a compaction press.

Pressureless sintering

[edit]Pressureless sintering is the sintering of a powder compact (sometimes at very high temperatures, depending on the powder) without applied pressure. This avoids density variations in the final component, which occurs with more traditional hot pressing methods.[21]

The powder compact (if a ceramic) can be created by slip casting, injection moulding, and cold isostatic pressing. After presintering, the final green compact can be machined to its final shape before being sintered.

Three different heating schedules can be performed with pressureless sintering: constant-rate of heating (CRH), rate-controlled sintering (RCS), and two-step sintering (TSS). The microstructure and grain size of the ceramics may vary depending on the material and method used.[21]

Constant-rate of heating (CRH), also known as temperature-controlled sintering, consists of heating the green compact at a constant rate up to the sintering temperature.[22] Experiments with zirconia have been performed to optimize the sintering temperature and sintering rate for CRH method. Results showed that the grain sizes were identical when the samples were sintered to the same density, proving that grain size is a function of specimen density rather than CRH temperature mode.

In rate-controlled sintering (RCS), the densification rate in the open-porosity phase is lower than in the CRH method.[22] By definition, the relative density, ρrel, in the open-porosity phase is lower than 90%. Although this should prevent separation of pores from grain boundaries, it has been proven statistically that RCS did not produce smaller grain sizes than CRH for alumina, zirconia, and ceria samples.[21]

Two-step sintering (TSS) uses two different sintering temperatures. The first sintering temperature should guarantee a relative density higher than 75% of theoretical sample density. This will remove supercritical pores from the body. The sample will then be cooled down and held at the second sintering temperature until densification is completed. Grains of cubic zirconia and cubic strontium titanate were significantly refined by TSS compared to CRH. However, the grain size changes in other ceramic materials, like tetragonal zirconia and hexagonal alumina, were not statistically significant.[21]

Microwave sintering

[edit]In microwave sintering, heat is sometimes generated internally within the material, rather than via surface radiative heat transfer from an external heat source. Some materials fail to couple and others exhibit run-away behavior, so it is restricted in usefulness. A benefit of microwave sintering is faster heating for small loads, meaning less time is needed to reach the sintering temperature, less heating energy is required and there are improvements in the product properties.[23]

A failing of microwave sintering is that it generally sinters only one compact at a time, so overall productivity turns out to be poor except for situations involving one of a kind sintering, such as for artists. As microwaves can only penetrate a short distance in materials with a high conductivity and a high permeability, microwave sintering requires the sample to be delivered in powders with a particle size around the penetration depth of microwaves in the particular material. The sintering process and side-reactions run several times faster during microwave sintering at the same temperature, which results in different properties for the sintered product.[23]

This technique is acknowledged to be quite effective in maintaining fine grains/nano sized grains in sintered bioceramics. Magnesium phosphates and calcium phosphates are the examples which have been processed through the microwave sintering technique.[24]

Densification, vitrification and grain growth

[edit]Sintering in practice is the control of both densification and grain growth. Densification is the act of reducing porosity in a sample, thereby making it denser. Grain growth is the process of grain boundary motion and Ostwald ripening to increase the average grain size. Many properties (mechanical strength, electrical breakdown strength, etc.) benefit from both a high relative density and a small grain size. Therefore, being able to control these properties during processing is of high technical importance. Since densification of powders requires high temperatures, grain growth naturally occurs during sintering. Reduction of this process is key for many engineering ceramics. Under certain conditions of chemistry and orientation, some grains may grow rapidly at the expense of their neighbours during sintering. This phenomenon, known as abnormal grain growth (AGG), results in a bimodal grain size distribution that has consequences for the mechanical, dielectric and thermal performance of the sintered material.

For densification to occur at a quick pace it is essential to have (1) an amount of liquid phase that is large in size, (2) a near complete solubility of the solid in the liquid, and (3) wetting of the solid by the liquid. The power behind the densification is derived from the capillary pressure of the liquid phase located between the fine solid particles. When the liquid phase wets the solid particles, each space between the particles becomes a capillary in which a substantial capillary pressure is developed. For submicrometre particle sizes, capillaries with diameters in the range of 0.1 to 1 micrometres develop pressures in the range of 175 pounds per square inch (1,210 kPa) to 1,750 pounds per square inch (12,100 kPa) for silicate liquids and in the range of 975 pounds per square inch (6,720 kPa) to 9,750 pounds per square inch (67,200 kPa) for a metal such as liquid cobalt.[3]

Densification requires constant capillary pressure where just solution-precipitation material transfer would not produce densification. For further densification, additional particle movement while the particle undergoes grain-growth and grain-shape changes occurs. Shrinkage would result when the liquid slips between particles and increases pressure at points of contact causing the material to move away from the contact areas, forcing particle centers to draw near each other.[3]

The sintering of liquid-phase materials involves a fine-grained solid phase to create the needed capillary pressures proportional to its diameter, and the liquid concentration must also create the required capillary pressure within range, else the process ceases. The vitrification rate is dependent upon the pore size, the viscosity and amount of liquid phase present leading to the viscosity of the overall composition, and the surface tension. Temperature dependence for densification controls the process because at higher temperatures viscosity decreases and increases liquid content. Therefore, when changes to the composition and processing are made, it will affect the vitrification process.[3]

Sintering mechanisms

[edit]Sintering occurs by diffusion of atoms through the microstructure. This diffusion is caused by a gradient of chemical potential – atoms move from an area of higher chemical potential to an area of lower chemical potential. The different paths the atoms take to get from one spot to another are the "sintering mechanisms" or "matter transport mechanisms".

In solid state sintering, the six common mechanisms are:[3]

- surface diffusion – diffusion of atoms along the surface of a particle

- vapor transport – evaporation of atoms which condense on a different surface

- lattice diffusion from surface – atoms from surface diffuse through lattice

- lattice diffusion from grain boundary – atom from grain boundary diffuses through lattice

- grain boundary diffusion – atoms diffuse along grain boundary

- plastic deformation – dislocation motion causes flow of matter.

Mechanisms 1–3 above are non-densifying (i.e. do not cause the pores and the overall ceramic body to shrink) but can still increase the area of the bond or "neck" between grains; they take atoms from the surface and rearrange them onto another surface or part of the same surface. Mechanisms 4–6 are densifying – atoms are moved from the bulk material or the grain boundaries to the surface of pores, thereby eliminating porosity and increasing the density of the sample.

Grain growth

[edit]A grain boundary (GB) is the transition area or interface between adjacent crystallites (or grains) of the same chemical and lattice composition, not to be confused with a phase boundary. The adjacent grains do not have the same orientation of the lattice, thus giving the atoms in GB shifted positions relative to the lattice in the crystals. Due to the shifted positioning of the atoms in the GB they have a higher energy state when compared with the atoms in the crystal lattice of the grains. It is this imperfection that makes it possible to selectively etch the GBs when one wants the microstructure to be visible.[25]

Striving to minimize its energy leads to the coarsening of the microstructure to reach a metastable state within the specimen. This involves minimizing its GB area and changing its topological structure to minimize its energy. This grain growth can either be normal or abnormal, a normal grain growth is characterized by the uniform growth and size of all the grains in the specimen. Abnormal grain growth is when a few grains grow much larger than the remaining majority.[26]

Grain boundary energy/tension

[edit]The atoms in the GB are normally in a higher energy state than their equivalent in the bulk material. This is due to their more stretched bonds, which gives rise to a GB tension . This extra energy that the atoms possess is called the grain boundary energy, . The grain will want to minimize this extra energy, thus striving to make the grain boundary area smaller and this change requires energy.[26]

"Or, in other words, a force has to be applied, in the plane of the grain boundary and acting along a line in the grain-boundary area, in order to extend the grain-boundary area in the direction of the force. The force per unit length, i.e. tension/stress, along the line mentioned is σGB. On the basis of this reasoning it would follow that:

with dA as the increase of grain-boundary area per unit length along the line in the grain-boundary area considered."[26][pg 478]

The GB tension can also be thought of as the attractive forces between the atoms at the surface and the tension between these atoms is due to the fact that there is a larger interatomic distance between them at the surface compared to the bulk (i.e. surface tension). When the surface area becomes bigger the bonds stretch more and the GB tension increases. To counteract this increase in tension there must be a transport of atoms to the surface keeping the GB tension constant. This diffusion of atoms accounts for the constant surface tension in liquids. Then the argument,

holds true. For solids, on the other hand, diffusion of atoms to the surface might not be sufficient and the surface tension can vary with an increase in surface area.[27]

For a solid, one can derive an expression for the change in Gibbs free energy, dG, upon the change of GB area, dA. dG is given by

which gives

is normally expressed in units of while is normally expressed in units of since they are different physical properties.[26]

Mechanical equilibrium

[edit]In a two-dimensional isotropic material the grain boundary tension would be the same for the grains. This would give angle of 120° at GB junction where three grains meet. This would give the structure a hexagonal pattern which is the metastable state (or mechanical equilibrium) of the 2D specimen. A consequence of this is that, to keep trying to be as close to the equilibrium as possible, grains with fewer sides than six will bend the GB to try keep the 120° angle between each other. This results in a curved boundary with its curvature towards itself. A grain with six sides will, as mentioned, have straight boundaries, while a grain with more than six sides will have curved boundaries with its curvature away from itself. A grain with six boundaries (i.e. hexagonal structure) is in a metastable state (i.e. local equilibrium) within the 2D structure.[26] In three dimensions structural details are similar but much more complex and the metastable structure for a grain is a non-regular 14-sided polyhedra with doubly curved faces. In practice all arrays of grains are always unstable and thus always grow until prevented by a counterforce.[28]

Grains strive to minimize their energy, and a curved boundary has a higher energy than a straight boundary. This means that the grain boundary will migrate towards the curvature.[clarification needed] The consequence of this is that grains with less than 6 sides will decrease in size while grains with more than 6 sides will increase in size.[29]

Grain growth occurs due to motion of atoms across a grain boundary. Convex surfaces have a higher chemical potential than concave surfaces, therefore grain boundaries will move toward their center of curvature. As smaller particles tend to have a higher radius of curvature and this results in smaller grains losing atoms to larger grains and shrinking. This is a process called Ostwald ripening. Large grains grow at the expense of small grains.

Grain growth in a simple model is found to follow:

Here G is final average grain size, G0 is the initial average grain size, t is time, m is a factor between 2 and 4, and K is a factor given by:

Here Q is the molar activation energy, R is the ideal gas constant, T is absolute temperature, and K0 is a material dependent factor. In most materials the sintered grain size is proportional to the inverse square root of the fractional porosity, implying that pores are the most effective retardant for grain growth during sintering.

Reducing grain growth

[edit]Solute ions

[edit]If a dopant is added to the material (example: Nd in BaTiO3) the impurity will tend to stick to the grain boundaries. As the grain boundary tries to move (as atoms jump from the convex to concave surface) the change in concentration of the dopant at the grain boundary will impose a drag on the boundary. The original concentration of solute around the grain boundary will be asymmetrical in most cases. As the grain boundary tries to move, the concentration on the side opposite of motion will have a higher concentration and therefore have a higher chemical potential. This increased chemical potential will act as a backforce to the original chemical potential gradient that is the reason for grain boundary movement. This decrease in net chemical potential will decrease the grain boundary velocity and therefore grain growth.

Fine second phase particles

[edit]If particles of a second phase which are insoluble in the matrix phase are added to the powder in the form of a much finer powder, then this will decrease grain boundary movement. When the grain boundary tries to move past the inclusion diffusion of atoms from one grain to the other, it will be hindered by the insoluble particle. This is because it is beneficial for particles to reside in the grain boundaries and they exert a force in opposite direction compared to grain boundary migration. This effect is called the Zener effect after the man who estimated this drag force to

where r is the radius of the particle and λ the interfacial energy of the boundary if there are N particles per unit volume their volume fraction f is

assuming they are randomly distributed. A boundary of unit area will intersect all particles within a volume of 2r which is 2Nr particles. So the number of particles n intersecting a unit area of grain boundary is:

Now, assuming that the grains only grow due to the influence of curvature, the driving force of growth is where (for homogeneous grain structure) R approximates to the mean diameter of the grains. With this the critical diameter that has to be reached before the grains ceases to grow:

This can be reduced to

so the critical diameter of the grains is dependent on the size and volume fraction of the particles at the grain boundaries.[30]

It has also been shown that small bubbles or cavities can act as inclusion

More complicated interactions which slow grain boundary motion include interactions of the surface energies of the two grains and the inclusion and are discussed in detail by C.S. Smith.[31]

Sintering of catalysts

[edit]Sintering is an important cause for loss of catalytic activity, especially on supported metal catalysts. It decreases the surface area of the catalyst and changes the surface structure.[32] For a porous catalytic surface, the pores may collapse due to sintering, resulting in loss of surface area. Sintering is in general an irreversible process.[33]

Small catalyst particles have the highest possible relative surface area and high reaction temperature, both factors that generally increase the reactivity of a catalyst. However, these factors are also the circumstances under which sintering occurs.[34] Specific materials may also increase the rate of sintering. On the other hand, by alloying catalysts with other materials, sintering can be reduced. Rare-earth metals in particular have been shown to reduce sintering of metal catalysts when alloyed.[35]

For many supported metal catalysts, sintering starts to become a significant effect at temperatures over 500 °C (932 °F).[32] Catalysts that operate at higher temperatures, such as a car catalyst, use structural improvements to reduce or prevent sintering. These improvements are in general in the form of a support made from an inert and thermally stable material such as silica, carbon or alumina.[36]

See also

[edit]- Abnormal grain growth – Phenomenon of certain material grains growing faster than others

- Capacitor discharge sintering – Fast electric current assisted sintering process

- Ceramic engineering – Science and technology of creating objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials

- Direct metal laser sintering – 3D printing technique

- Energetically modified cement – Class of cements, mechanically processed to transform reactivity

- Frit – Fused, quenched and granulated ceramic

- High-temperature superconductivity – Superconductive behavior at temperatures much higher than absolute zero

- Metal clay – Craft material of metal particles and a plastic binder

- Room-temperature densification method – Non-thermal densification method for ceramics

- Selective laser sintering – 3D printing technique, a rapid prototyping technology, that includes Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS).

- Spark plasma sintering – Sintering technique

- W. David Kingery – Ceramic engineer – a pioneer of sintering methods

- Yttria-stabilized zirconia – Ceramic with room temperature stable cubic crystal structure

References

[edit]- ^ "sintered". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "sinter". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kingery, W. David; Bowen, H. K.; Uhlmann, Donald R. (April 1976). Introduction to Ceramics (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Academic Press. ISBN 0-471-47860-1.

- ^ Leriche, Anne; Cambier, Francis; Hampshire, Stuart (2017), "Sintering of Ceramics", Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering, Elsevier, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-803581-8.10288-7, ISBN 978-0-12-803581-8, retrieved 2023-07-04

- ^ Hansen, Tony. "Sintering". digitalfire.com. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ "Ceramic Sintering Explained". Wunder-Mold. 2023-02-02. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ German, R. M. (2020). Titanium sintering science: A review of atomic events during densification. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 89, 105214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2020.105214

- ^ Bronchy, M.; Roach, L.; Mendizabal, L.; Feautrier, C.; Durand, E.; Heintz, J.-M.; Duguet, E.; Tréguer-Delapierre, M. (18 January 2022). "Improved Low Temperature Sinter Bonding Using Silver Nanocube Superlattices". J. Phys. Chem. C. 126 (3): 1644–1650. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c09125. eISSN 1932-7455. ISSN 1932-7447.

- ^ "Porex Custom Plastics: Porous Plastics & Porous Polymers". www.porex.com. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ^ Uhl, A.R.; et al. (2014). "Liquid-selenium-enhanced grain growth of nanoparticle precursor layers for CuInSe2 solar cell absorbers". Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications. 23 (9): 1110–1119. doi:10.1002/pip.2529. S2CID 97768071.

- ^ Orrù, Roberto; Licheri, Roberta; Locci, Antonio Mario; Cincotti, Alberto; Cao, Giacomo (February 2009). "Consolidation/synthesis of materials by electric current activated/assisted sintering". Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 63 (4–6): 127–287. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2008.09.003.

- ^ Grasso, Salvatore; Sakka, Yoshio; Maizza, Giovanni (October 2009). "Electric current activated/assisted sintering (ECAS): a review of patents 1906–2008". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 10 (5) 053001. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/10/5/053001. ISSN 1468-6996. PMC 5090538. PMID 27877308.

- ^ a b c d Grasso, S; Sakka, Y; Maizza, G (2009). "Electric current activated/assisted sintering (ECAS): a review of patents 1906–2008". Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 10 (5) 053001. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/10/5/053001. PMC 5090538. PMID 27877308.

- ^ Tuan, W.H.; Guo, J.K. (2004). Multi-phased ceramic materials: processing and potential. Springer. ISBN 3-540-40516-X.

- ^ Hulbert, D. M.; et al. (2008). "The Absence of Plasma in' Spark Plasma Sintering'". Journal of Applied Physics. 104 (3): 033305–033305–7. Bibcode:2008JAP...104c3305H. doi:10.1063/1.2963701. S2CID 54726651.

- ^ Anselmi-Tamburini, U. et al. in Sintering: Nanodensification and Field Assisted Processes (Castro, R. & van Benthem, K.) (Springer Verlag, 2012).

- ^ Palmer, R.E.; Wilde, G. (December 22, 2008). Mechanical Properties of Nanocomposite Materials. EBL Database: Elsevier Ltd. ISBN 978-0-08-044965-4.

- ^ K. Sairam; J.K. Sonber; T.S.R.Ch. Murthy; A.K. Sahu; R.D. Bedse; J.K. Chakravartty (2016). "Pressureless sintering of chromium diboride using spark plasma sintering facility". International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 58: 165–171. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2016.05.002.

- ^ Fais, A. "Discharge sintering of hard metal cutting tools". International Powder Metallurgy Congress and Exhibition, Euro PM 2013

- ^ Balagna, Cristina; Fais, Alessandro; Brunelli, Katya; Peruzzo, Luca; Horynová, Miroslava; Čelko, Ladislav; Spriano, Silvia (2016). "Electro-sinter-forged Ni–Ti alloy". Intermetallics. 68: 31–41. doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2015.08.016.

- ^ a b c d Maca, Karel (2009). "Microstructure evolution during pressureless sintering of bulk oxide ceramics". Processing and Application of Ceramics. 3 (1–2): 13–17. doi:10.2298/pac0902013m.

- ^ a b Maca, Karl; Simonikova, Sarka (2005). "Effect of sintering schedule on grain size of oxide ceramics". Journal of Materials Science. 40 (21): 5581–5589. Bibcode:2005JMatS..40.5581M. doi:10.1007/s10853-005-1332-1. S2CID 137157248.

- ^ a b Oghbaei, Morteza; Mirzaee, Omid (2010). "Microwave versus conventional sintering: A review of fundamentals, advantages and applications". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 494 (1–2): 175–189. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.01.068.

- ^ Babaie, Elham; Ren, Yufu; Bhaduri, Sarit B. (23 March 2016). "Microwave sintering of fine grained MgP and Mg substitutes with amorphous tricalcium phosphate: Structural, and mechanical characterization". Journal of Materials Research. 31 (8): 995–1003. Bibcode:2016JMatR..31..995B. doi:10.1557/jmr.2016.84. S2CID 139007302.

- ^ Smallman R. E., Bishop, Ray J (1999). Modern physical metallurgy and materials engineering: science, process, applications. Oxford : Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-4564-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Mittemeijer, Eric J. (2010). Fundamentals of Materials Science The Microstructure–Property Relationship Using Metals as Model Systems. Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York. pp. 463–496. ISBN 978-3-642-10499-2.

- ^ Kang, Suk-Joong L. (2005). Sintering: Densification, Grain Growth, and Microstructure. Elsevier Ltd. pp. 9–18. ISBN 978-0-7506-6385-4.

- ^ Cahn, Robert W. and Haasen, Peter (1996). Physical Metallurgy (Fourth ed.). Elsevier Science. pp. 2399–2500. ISBN 978-0-444-89875-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carter, C. Barry; Norton, M. Grant (2007). Ceramic Materials: Science and Engineering. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. pp. 427–443. ISBN 978-0-387-46270-7.

- ^ Cahn, Robert W. and Haasen, Peter (1996). Physical Metallurgy (Fourth ed.). Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-444-89875-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith, Cyril S. (February 1948). "Introduction to Grains, Phases and Interphases: an Introduction to Microstructure".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b G. Kuczynski (6 December 2012). Sintering and Catalysis. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4684-0934-5.

- ^ Bartholomew, Calvin H (2001). "Mechanisms of catalyst deactivation". Applied Catalysis A: General. 212 (1–2): 17–60. Bibcode:2001AppCA.212...17B. doi:10.1016/S0926-860X(00)00843-7.

- ^ Harris, P (1986). "The sintering of platinum particles in an alumina-supported catalyst: Further transmission electron microscopy studies". Journal of Catalysis. 97 (2): 527–542. doi:10.1016/0021-9517(86)90024-2.

- ^ Figueiredo, J. L. (2012). Progress in Catalyst Deactivation: Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Catalyst Deactivation, Algarve, Portugal, May 18–29, 1981. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 11. ISBN 978-94-009-7597-2.

- ^ Chorkendorff, I.; Niemantsverdriet, J. W. (6 March 2006). Concepts of Modern Catalysis and Kinetics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-60564-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Chiang, Yet-Ming; Birnie, Dunbar P.; Kingery, W. David (May 1996). Physical Ceramics: Principles for Ceramic Science and Engineering. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-59873-9.

- Green, D.J.; Hannink, R.; Swain, M.V. (1989). Transformation Toughening of Ceramics. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-6594-5.

- German, R.M. (1996). Sintering Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-05786-X.

- Kang, Suk-Joong L. (2005). Sintering (1st ed.). Oxford: Elsevier, Butterworth Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-6385-5.

External links

[edit]Sintering

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Principles

Sintering is a materials processing technique that involves compacting and forming a solid mass from particulate materials, such as powders, through the application of heat and/or pressure without causing complete melting or liquefaction of the material. This process transforms loose or pre-compacted powders into a coherent body with enhanced mechanical properties, often achieving densities approaching that of the fully dense material. Unlike melting or casting methods, which rely on full liquefaction and subsequent solidification, sintering maintains the solid-state integrity of the particles while promoting bonding through atomic diffusion at interfaces.[1] The fundamental principle driving sintering is the reduction of surface free energy inherent in finely divided powders, which possess a high surface-to-volume ratio. This excess energy motivates the system to minimize total interfacial area by forming interparticle contacts, thereby lowering the overall Gibbs free energy. Key parameters influencing the sintering outcome include temperature, typically maintained at 70-80% of the material's absolute melting point to facilitate diffusion without melting; holding time, which allows sufficient atomic mobility; processing atmosphere, such as inert gases or vacuum to inhibit oxidation or unwanted reactions; and initial particle size, where smaller particles accelerate sintering due to shorter diffusion paths and greater curvature-driven forces.[13][14][15] At a high level, sintering progresses through three distinct stages. In the initial stage, necks begin to form at points of contact between adjacent particles via surface and volume diffusion, with minimal overall densification occurring. The intermediate stage features continued neck growth, pore channel narrowing, and significant shrinkage as interconnected porosity reduces. Finally, the densification stage eliminates remaining isolated pores, leading to near-full density, though grain growth may also contribute to microstructural evolution. These stages collectively enable the consolidation of powders into robust components.[16][9] Sintering finds common application in powder metallurgy for producing metal parts, ceramics manufacturing for structural and functional components, and additive manufacturing as a critical densification step following layer-by-layer powder deposition. In each context, it ensures the transformation of as-formed green bodies into high-performance materials with tailored microstructures.[17][18]Historical Overview

Sintering traces its origins to ancient civilizations, where it was employed in the production of ceramics and early metallic artifacts. One of the earliest known applications dates back to around 5000 BCE in ancient Egypt, where faience—a sintered composite of quartz powder, lime, and alkali glaze—was crafted into beads, amulets, and decorative items, demonstrating controlled heating to fuse materials without full melting.[19] In prehistoric times, the firing of clay pottery in open pits represented an empirical form of sintering, enhancing strength and durability through thermal bonding of particles, a practice that spread globally and formed the basis for ceramic technologies.[20] By the medieval period, rudimentary powder compaction techniques emerged in metallurgy, such as the use of iron sponge (a porous, partially sintered iron product from bloomeries) compacted and forged into tools, marking early steps toward structured powder processing in Europe and Asia.[21] The 19th and early 20th centuries saw sintering evolve from artisanal methods to industrial processes, particularly in powder metallurgy. A pivotal milestone occurred in 1908 when William D. Coolidge at General Electric developed a method to produce ductile tungsten filaments by compacting and sintering tungsten powder, enabling reliable incandescent light bulbs and revolutionizing electrical engineering.[22] By the 1920s, powder metallurgy formalized as a discipline, with manufacturers adopting sintering for producing cutting tools, self-lubricating bearings, and tungsten carbide components, driven by advancements in powder production and controlled atmospheres.[23] Key theoretical contributions included Anders H.M. Andreasen's work in the late 1920s on continuous particle size distributions, which optimized packing density and sintering efficiency for better material uniformity.[24] Post-World War II advancements accelerated sintering's role in high-performance applications, particularly in nuclear and aerospace sectors. In the 1950s, sintering became essential for fabricating uranium dioxide fuel pellets, where powder compaction followed by high-temperature sintering produced dense ceramic rods for nuclear reactors, supporting the global expansion of atomic energy programs. Aerospace industries leveraged sintering for superalloys and refractory metals, enabling components like turbine blades that withstood extreme conditions in jet engines and spacecraft.[25] In the modern era, sintering integrated with additive manufacturing since the 1980s, exemplified by the invention of selective laser sintering (SLS) in 1986 by Carl Deckard, which used lasers to selectively fuse powder layers for rapid prototyping and complex geometries.[26] Advancements in the 2010s built on earlier field-assisted sintering techniques, such as spark plasma sintering (SPS) developed in the 1960s, include patents like US20110236713A1 (2011) enabling ultra-rapid densification of nanomaterials under electric fields, reducing processing times from hours to minutes while preserving microstructures for advanced ceramics and metals.[27]Fundamentals

Driving Forces and Thermodynamics

The primary driving force for sintering is the reduction in the total surface free energy of the powder compact, as the high surface-to-volume ratio of fine particles creates an excess energy that the system seeks to minimize through bonding and densification.[28] This process is inherently curvature-driven, with material transport occurring via diffusion from regions of high positive curvature (convex particle surfaces, higher energy) to regions of negative curvature (concave necks between particles, lower energy), thereby smoothing interfaces and reducing overall surface area.[14] The curvature difference establishes a gradient that propels atomic or ionic species toward lower-energy configurations, initiating neck formation in the early stages of sintering.[29] Thermodynamically, sintering proceeds to minimize the Gibbs free energy of the system, where the change is given by ; here, the enthalpic contribution is negative due to the release of surface energy as interfaces form, while the entropic term is generally smaller and often negative owing to reduced configurational freedom, ensuring for spontaneous progression.[30] The surface free energy directly contributes to this by increasing the chemical potential at curved interfaces, creating gradients that drive mass transport.[31] At the particle necks, these chemical potential gradients arise from Laplace pressure differences, with the potential at a curved surface expressed as , where is the chemical potential of a flat surface, is the atomic volume, and is the mean curvature (positive for convex, negative for concave); this formulation shows how sharper curvatures at particle contacts generate higher potentials, promoting influx to the neck.[29] For a spherical particle of radius , the gradient simplifies to over convex regions, underscoring the inverse size dependence. A key relation governing the size dependence of sintering is Herring's scaling law, which predicts how processing time scales with particle size under self-similar geometries.[14] The law states that the time required to achieve equivalent microstructural evolution scales as , where is the characteristic length (e.g., particle radius), is the relevant diffusion coefficient, and is the scaling exponent dependent on the transport mechanism: for volume (lattice) diffusion, for grain-boundary or surface diffusion.[32] To derive this for volume diffusion (), consider a self-similar system where scaling the linear dimensions by a factor enlarges all features proportionally. The driving force, manifested as chemical potential difference , scales inversely with size. The concentration gradient driving diffusion then scales as , but since the diffusion path length also scales with , the atomic flux . The linear shrinkage rate or neck growth velocity . Thus, the relative rate , implying that time for a fixed relative change integrates to ; for the scaled system, , confirming .[14] This derivation highlights why finer powders sinter faster, as smaller reduces required time cubically for volume-diffusion-limited processes. Influencing factors include temperature, which exponentially activates diffusion via the Arrhenius relation , where is the pre-exponential factor, is the activation energy, is the gas constant, and is absolute temperature; thus, sintering rates increase dramatically above ~0.5-0.7 of the melting point, as higher lowers the energy barrier for atomic jumps.[33] The sintering atmosphere also plays a role by modulating surface chemistry, particularly through oxidation or reduction; oxidizing environments can form stable oxide layers that inhibit diffusion and raise effective surface energy, while reducing atmospheres (e.g., hydrogen) remove these oxides, lowering barriers and enhancing densification, as seen in iron powders where oxide reduction activation energies exceed 400 kJ/mol without proper control.[34]Sintering Mechanisms

Sintering involves several atomic and molecular transport mechanisms that drive particle bonding and densification by reducing surface energy through curvature gradients. The primary mechanisms include surface diffusion, lattice diffusion, grain boundary diffusion, and vapor transport. Surface diffusion entails the movement of atoms along the free surfaces of particles, which is typically dominant at lower temperatures due to its relatively low activation energy, facilitating initial neck formation without contributing to bulk densification. Lattice diffusion occurs through the crystal volume, requiring higher temperatures and activation energies, and plays a key role in transporting material from high-curvature regions like necks to pores. Grain boundary diffusion involves atom transport along interfaces between grains, offering a faster pathway than lattice diffusion at intermediate temperatures, especially in fine-grained materials. Vapor transport, involving evaporation from convex surfaces and condensation on concave ones, is less prevalent but significant in systems with high vapor pressure or under vacuum conditions, such as certain oxides.[35][36] Neck growth models describe the initial bonding between particles. The Frenkel model applies to viscous flow in the early stage, treating the material as a viscous fluid where surface tension drives neck radius growth proportional to , with , where is particle radius, is surface tension, is viscosity, and is time; this is particularly relevant for amorphous or polymer systems but also approximates crystalline behavior at high temperatures. For crystalline materials, diffusion-based models, such as those for evaporation-condensation, predict similar parabolic growth kinetics but via mass transport paths like vapor phase migration from the neck to particle surfaces.[37][35] In the intermediate stage, densification proceeds via pore shrinkage, often modeled using Coble's creep relation adapted for sintering, where grain boundary diffusion controls the rate: Here, represents the relative densification rate (linear shrinkage rate), is the surface energy driving curvature-induced stress, is the atomic volume, is the grain boundary diffusivity, is the effective grain boundary thickness (typically 0.5–1 nm), is Boltzmann's constant, is absolute temperature, and is the average grain diameter. This relation underscores the inverse cubic dependence on grain size, emphasizing the benefit of fine microstructures for enhanced densification, and assumes pores are located at grain boundaries acting as vacancy sinks. In this stage, lattice diffusion from grain boundaries to pores also contributes to channel shrinkage, transitioning open porosity to isolated pores.[38][36] The initial stage focuses on neck development between adjacent particles, primarily through surface diffusion, which rounds particle contacts and increases contact area while maintaining constant volume. As sintering progresses to the intermediate stage, interconnected pores shrink via lattice diffusion, with material flux from grain edges to pore interiors reducing porosity from about 40% to 10%, marking the onset of significant densification. In the final stage, closed pores, now spherical and grain-boundary attached, continue to diminish through grain boundary diffusion, though at a slower rate due to reduced driving force, ultimately yielding high-density microstructures.[39]Kinetics and Stages

Sintering progresses through three distinct stages characterized by evolving microstructure and densification levels. The initial stage involves the formation and growth of necks at particle contacts, driven by surface diffusion and curvature gradients, resulting in minimal densification of less than 5% as the relative density rises from the green body packing fraction to approximately 60-70%.[40] In this phase, the process is dominated by rapid local mass transport without significant overall shrinkage.[41] The intermediate stage follows, marked by the coalescence of necks into continuous channels of interconnected pores along particle boundaries, enabling substantial densification up to 90-95% relative density through channel shrinkage and pore narrowing.[40] Pore interconnectivity persists, but the geometry shifts toward cylindrical pores, with mass transport increasingly limited by longer diffusion paths. The final stage occurs at high densities above 90%, where pores become isolated and spherical, often trapped within grains, leading to slower densification rates as transport distances lengthen and pore stability increases due to reduced connectivity.[40] Kinetic models describe the temporal evolution of these stages using rate equations that incorporate activation energies specific to the dominant mass transport mechanisms, such as lattice diffusion (typically 300-600 kJ/mol for ceramics like alumina) or grain boundary diffusion (200-400 kJ/mol).[43] These energies reflect the temperature sensitivity of atomic mobility, with higher values indicating volume-controlled processes over surface or boundary paths; the kinetics are briefly tied to diffusion mechanisms like those outlined in sintering theory.[44] Isothermal sintering curves exhibit exponential densification with time at constant temperature, following Arrhenius behavior, whereas non-isothermal curves under varying heating rates show shifted trajectories due to transient thermal gradients affecting activation.[14] A key advancement in modeling is the master sintering curve (MSC) approach, introduced by Su and Johnson, which unifies densification predictions across thermal histories by normalizing microstructural and thermal effects. The method assumes the densification rate follows , where captures density-dependent microstructure, is the activation energy, and the exponential term governs thermal activation. Integrating this under non-isothermal conditions yields the normalized parameter derived by substituting for heating rate and approximating the Arrhenius integral for high temperatures, where the term normalizes the temperature scaling. This represents a dimensionless thermal work equivalent, plotted against to form the invariant MSC once (determined iteratively from dilatometry data) and are fitted. Applications include forecasting final density for optimized cycles, such as in alumina where MSC accurately extrapolates from ramped heating to complex profiles, reducing trial experiments.[45] Sintering rates are influenced by initial conditions, notably particle size distribution (PSD), where broader PSDs slow overall kinetics as fine particles densify rapidly but are hindered by coarser ones, particularly in the intermediate stage, reducing densification by up to 10-20% compared to monodisperse powders.[46] Green body uniformity also plays a critical role; heterogeneous packing leads to variable local densities and pore distributions, accelerating abnormal pore growth and distorting kinetics, whereas uniform compacts ensure consistent rates and minimize warping during progression through stages.[47]Types of Sintering Processes

Solid-State Sintering

Solid-state sintering is a process in which compacted powders are heated to temperatures below the melting point of the material, typically 0.5 to 0.8 times the absolute melting temperature (Tm), to achieve bonding and densification through atomic diffusion mechanisms without the formation of any liquid phase. This diffusion-driven process begins with the formation of necks between adjacent particles due to surface and volume diffusion, followed by neck growth and particle coalescence, ultimately leading to pore elimination and increased density. The process is divided into initial, intermediate, and final stages, where the initial stage focuses on neck formation, the intermediate on pore channel closure, and the final on isolated pore shrinkage.[48][49] A primary advantage of solid-state sintering is the retention of high material purity, as it avoids compositional changes associated with melting or liquid phases, making it particularly suitable for refractory materials with high melting points that cannot tolerate liquid formation. This method enables the production of dense components with excellent mechanical properties, such as enhanced strength and thermal conductivity, while preserving the original powder chemistry. It is widely used for materials where contamination must be minimized, allowing for the fabrication of high-performance ceramics and metals.[50][48] Key parameters influencing solid-state sintering include temperature, typically ranging from 1000°C to 2000°C depending on the material, and holding times of 1 to 10 hours to allow sufficient diffusion. Atmosphere control is essential, with vacuum or inert gases employed for metals to prevent oxidation, while ceramics may use air or controlled oxygen partial pressures. Particle size, initial green density, and heating rate also play critical roles, as finer powders accelerate diffusion but may increase agglomeration risks.[51][48] For example, in the sintering of alumina (Al₂O₃) powders, solid-state diffusion predominates typically at 1500-1700°C, enabling the achievement of 95-99% theoretical density through controlled heating in air, resulting in translucent or transparent ceramics for optical applications. Similarly, tungsten powders undergo solid-state sintering at 1500-2000°C in hydrogen or vacuum atmospheres for 1-5 hours, yielding dense heavy alloys with 95-98% density suitable for radiation shielding and high-temperature components. These examples illustrate how optimized parameters can drive near-full densification via solid diffusion alone.[51][52][53]Liquid-Phase Sintering

Liquid-phase sintering is a densification process in which a transient liquid phase forms during heating, facilitating rapid particle bonding and microstructure evolution without full melting of the compact. This technique is particularly effective for materials systems where a low-melting additive or eutectic composition generates the liquid, promoting enhanced mass transport compared to solid-state methods. The liquid typically arises from localized melting at particle contacts due to eutectic formation, enabling capillary forces to drive rearrangement and densification. The mechanism involves three primary stages: initial particle rearrangement facilitated by capillary action of the liquid, solution-reprecipitation where soluble species dissolve in the liquid and reprecipitate at high-curvature sites to smooth particle interfaces, and final densification of the solid skeleton through solid-state diffusion and Ostwald ripening. Eutectic liquids form preferentially at interparticle necks, wetting the solids and penetrating pores to redistribute material efficiently. These concurrent processes reduce porosity by promoting flow and diffusion, leading to a more uniform microstructure upon solidification. A key aspect of liquid penetration in Kingery's model is governed by capillary flow, where the depth of liquid infiltration into pores, , scales as , with representing the liquid-vapor surface tension, the time, and the liquid viscosity. This relationship, derived from Poiseuille flow in capillaries, highlights how higher surface tension and lower viscosity accelerate liquid spreading, enabling rapid wetting and rearrangement. The full expression incorporates pore radius and contact angle, but the proportionality underscores the dominance of interfacial energy and fluidity in early-stage dynamics. Process parameters critically influence outcomes, including a liquid volume fraction of 5-20% to balance densification and structural integrity, temperatures slightly above the eutectic point (e.g., 1310°C for WC-Co systems) to form the liquid transiently, and additives such as cobalt or glass formers to induce melting without excessive flow. Optimal control of these ensures the liquid wets the solid phase effectively while minimizing grain growth.[54] This method yields faster densification rates, often achieving over 98% theoretical density in minutes, as seen in WC-Co cemented carbides used for tool steels, where the cobalt liquid enables near-full consolidation at moderate temperatures. Such outcomes enhance mechanical properties like hardness and toughness, making liquid-phase sintering ideal for complex shapes in powder metallurgy.Pressure-Assisted Sintering

Pressure-assisted sintering involves the application of external mechanical pressure during the heating process to enhance densification of powder compacts, distinguishing it from pressureless methods by accelerating particle rearrangement and pore closure.[55] The primary techniques include hot pressing, which applies uniaxial pressure through a die and punches, and hot isostatic pressing (HIP), which employs isotropic pressure via a high-pressure gas environment, typically argon.[56] Uniaxial hot pressing is suitable for simpler geometries and allows direct control over deformation direction, while isotropic HIP provides uniform pressure distribution, minimizing shape distortions and enabling complex part consolidation without dies.[57] These methods yield significant benefits in achieving high densities and refined microstructures. Densification routinely reaches near-theoretical levels exceeding 99% of the material's theoretical density, effectively eliminating residual porosity that persists in pressureless sintering.[58] Additionally, the applied pressure lowers the required sintering temperature by 100-200°C compared to conventional processes, reducing energy consumption and limiting grain growth to preserve mechanical properties.[59] A key theoretical framework for understanding densification under pressure is the Ashby-House model, which describes the process through viscous flow mechanisms in porous bodies. The model posits that the densification rate , where is the relative density, is driven by the applied stress opposing the material's viscous resistance . The governing equation is for viscous flow dominance. To derive this, consider the porous compact as a continuum with effective viscosity , where external pressure induces volumetric strain. The uniaxial strain rate under stress is from linear viscous rheology, but accounting for the three-dimensional pore collapse and relative density evolution yields the factor when integrating the bulk modulus relation for near-full density, leading to the simplified form for pressure-assisted regimes.[60] Applications of pressure-assisted sintering are prominent in processing refractory metals and advanced ceramics, where high densities are critical for thermal and structural performance. For refractory metals like tungsten and molybdenum alloys, hot pressing at 100-500 MPa enables consolidation at 1300-1600°C with cycle times of 30-60 minutes, achieving full densification while controlling grain size.[61] In ceramics such as zirconia and silicon carbide, HIP at similar pressures and temperatures produces pore-free components for aerospace and nuclear uses, with holding times typically 30-60 minutes to balance densification and creep.[62] These processes are particularly valued in industries requiring materials with superior creep resistance and fracture toughness.Sintering by Material

Ceramic Sintering

Ceramic sintering primarily addresses the processing of brittle, ionic-bonded materials such as oxide ceramics including alumina (Al₂O₃) and zirconia (ZrO₂), and non-oxide ceramics like silicon carbide (SiC) and silicon nitride (Si₃N₄).[63] Oxide ceramics typically require sintering temperatures between 1200°C and 1800°C to achieve densification without melting, while non-oxide ceramics often demand higher temperatures exceeding 2000°C due to their covalent bonding and thermal stability.[64][65] These elevated temperatures drive atomic diffusion and particle rearrangement, essential for overcoming the low self-diffusivity inherent in ceramics.[66] Common processes for ceramic sintering involve two-step approaches to control microstructure and minimize defects, starting with presintering at intermediate temperatures to form a porous green body, followed by hot isostatic pressing (HIP) at higher pressures and temperatures to close residual pores and attain near-full density.[67] Sintering aids are frequently incorporated to lower activation energies for diffusion; for instance, small additions of MgO (0.1-0.5 wt%) in alumina form spinel phases at grain boundaries, promoting densification while inhibiting excessive grain growth and abnormal coarsening.[68][69] In zirconia, yttria or calcia stabilizers are used alongside to maintain the tetragonal phase during sintering, enhancing toughness.[70] Key challenges in ceramic sintering arise from the materials' brittleness and tendency toward anisotropic shrinkage, where differential contraction in various directions can induce internal stresses, warping, or cracking during cooling.[71] To prevent such defects, controlled heating rates of 1-5°C/min are employed, particularly in the 800-1400°C range, allowing gradual binder burnout and stress relaxation without thermal shock.[72][73] Optimized ceramic sintering yields high-density (>99% theoretical) or translucent microstructures, enabling applications in electrical insulators where alumina provides high dielectric strength and thermal stability, and in biomaterials such as zirconia-based hip implants that offer biocompatibility and wear resistance.[74][75] These outcomes rely on precise control of densification to eliminate porosity, as referenced in broader microstructural evolution discussions.[76]Metallic Powder Sintering

Metallic powder sintering is a thermal process in powder metallurgy where compacted metal powders are heated to 70-90% of the material's absolute melting point, enabling solid-state diffusion and bonding between particles without liquefaction. This temperature range facilitates neck formation and densification while preserving the powder's shape integrity. For instance, iron powders, with a melting point of 1538°C, are typically sintered at around 1100°C to achieve adequate metallurgical bonding. The ductility of metals allows for enhanced deformation and particle rearrangement during this stage, distinguishing it from more brittle ceramic systems. A critical aspect of metallic sintering is the use of protective atmospheres, such as the reducing hydrogen (H2) or inert nitrogen (N2), to mitigate oxidation of reactive metal surfaces, which could otherwise form insulating oxide layers that impede diffusion and reduce ductility. These atmospheres ensure clean particle interfaces and optimal mechanical properties in the final compact, with hydrogen actively removing surface oxides through chemical reduction while nitrogen prevents further oxidation. This sintering approach excels in producing cost-effective, complex-shaped parts via near-net forming, minimizing waste and secondary machining in powder metallurgy applications like automotive gears and tools. However, the resulting materials often display lower strength than wrought equivalents, with residual porosity (typically 5-15%) creating stress concentrations that accelerate fatigue failure under cyclic loading. For specialized alloys, sintering parameters are tailored to address compositional challenges; stainless steels require temperatures exceeding 1150°C to reduce persistent chromium oxides and attain corrosion resistance. Superalloys, such as nickel-based variants, benefit from powder metallurgy sintering to yield fine-grained microstructures for high-temperature aerospace parts, enhancing creep and oxidation resistance. Post-sintering infiltration with low-melting metals like copper fills interconnecting pores, boosting density to over 98% and improving overall ductility and load-bearing capacity. During this process, grain growth is moderated to maintain the enhanced ductility inherent to metallic structures.Polymer Sintering

Polymer sintering refers to the process of consolidating polymer powders or particles into a dense solid through controlled heating, typically occurring via viscous flow mechanisms rather than atomic diffusion seen in inorganic materials. This process leverages the polymer's ability to soften and flow at relatively low temperatures, enabling the fusion of particles driven primarily by surface tension forces that promote neck formation and coalescence between adjacent particles.[77] Unlike solid-state sintering in metals or ceramics, polymer sintering does not rely on long-range diffusion but instead on the viscoelastic deformation and merging of molten or semi-molten particles, resulting in pore elimination and densification over short durations.[78] The unique aspects of polymer sintering include processing temperatures generally ranging from 100°C to 300°C, which align with the glass transition or melting points of common thermoplastics like polyamides or polystyrenes, allowing operation below degradation thresholds for many materials. Due to the inherently low viscosity of polymer melts (often 10^2 to 10^4 Pa·s at processing temperatures), sintering times are brief, typically spanning seconds to minutes, which facilitates rapid production cycles compared to high-temperature inorganic sintering. For instance, in amorphous polymers such as polystyrene, sintering proceeds through Newtonian viscous flow, where surface tension (around 20-40 mN/m) drives the coalescence, achieving significant densification in under 10 minutes at 230-260°C.[78] This low-viscosity regime minimizes energy input while enabling precise control over microstructure, though viscoelastic effects can influence the rate of pore collapse during coalescence.[79] Applications of polymer sintering are prominent in producing self-lubricating components, such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) bearings, where sintering at approximately 360-380°C fuses fine powders into porous structures that retain lubricants and exhibit low friction coefficients (around 0.05-0.1). In additive manufacturing, particularly selective laser sintering (SLS), polymer powders like polyamide-12 (PA12) are sintered layer-by-layer to create complex prototypes and functional parts, enabling customized geometries with densities up to 95% without support structures.[80] These techniques are widely adopted in aerospace and automotive sectors for lightweight, durable components. Key challenges in polymer sintering include thermal degradation, which can occur above 250-300°C for many thermoplastics, leading to chain scission, reduced molecular weight, and diminished mechanical properties like tensile strength dropping by 20-30% after multiple cycles. Achieving uniform density without residual voids is difficult due to uneven heating or particle packing, potentially resulting in porosity levels of 5-10% that compromise part integrity; strategies like controlled cooling rates (1-5°C/min) help mitigate void formation during coalescence.[81] Additionally, in 3D printing contexts, recycled powders exacerbate degradation, causing surface defects and inconsistent sintering.[82]Advanced Sintering Techniques

Electric Current Assisted Sintering