Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Salsa20

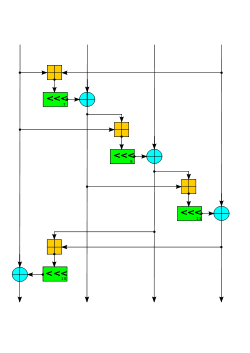

View on Wikipedia The Salsa quarter-round function. Four parallel copies make a round. | |

| General | |

|---|---|

| Designers | Daniel J. Bernstein |

| First published | 2007 (designed 2005)[1] |

| Successors | ChaCha |

| Related to | Rumba20 |

| Certification | eSTREAM portfolio |

| Cipher detail | |

| Key sizes | 128 or 256 bits |

| State size | 512 bits |

| Structure | ARX |

| Rounds | 20 |

| Speed | 3.91 cpb on an Intel Core 2 Duo[2] |

| Best public cryptanalysis | |

| 2008 cryptanalysis breaks 8 out of 20 rounds to recover the 256-bit secret key in 2251 operations, using 231 keystream pairs.[3] | |

Salsa20 and the closely related ChaCha are stream ciphers developed by Daniel J. Bernstein. Salsa20, the original cipher, was designed in 2005, then later submitted to the eSTREAM European Union cryptographic validation process by Bernstein. ChaCha is a modification of Salsa20 published in 2008. It uses a new round function that increases diffusion and increases performance on some architectures.[4]

Both ciphers are built on a pseudorandom function based on add–rotate–XOR (ARX) operations — 32-bit addition, bitwise addition (XOR) and rotation operations. The core function maps a 256-bit key, a 64-bit nonce, and a 64-bit counter to a 512-bit block of the key stream (a Salsa version with a 128-bit key also exists). This gives Salsa20 and ChaCha the unusual advantage that the user can efficiently seek to any position in the key stream in constant time. Salsa20 offers speeds of around 4–14 cycles per byte in software on modern x86 processors,[5] and reasonable hardware performance. It is not patented, and Bernstein has written several public domain implementations optimized for common architectures.[6]

Structure

[edit]Internally, the cipher uses bitwise addition ⊕ (exclusive OR), 32-bit addition mod 232 ⊞, and constant-distance rotation operations <<< on an internal state of sixteen 32-bit words. Using only add-rotate-xor operations avoids the possibility of timing attacks in software implementations. The internal state is made of sixteen 32-bit words arranged as a 4×4 matrix.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

The initial state is made up of eight words of key ( ), two words of stream position ( ), two words of nonce (essentially additional stream position bits) ( ), and four fixed words ( ):

| "expa" | Key | Key | Key |

| Key | "nd 3" | Nonce | Nonce |

| Pos. | Pos. | "2-by" | Key |

| Key | Key | Key | "te k" |

The constant words spell "expand 32-byte k" in ASCII (i.e. the 4 words are "expa", "nd 3", "2-by", and "te k"). This is an example of a nothing-up-my-sleeve number. The core operation in Salsa20 is the quarter-round QR(a, b, c, d) that takes a four-word input and produces a four-word output:

b ^= (a + d) <<< 7; c ^= (b + a) <<< 9; d ^= (c + b) <<< 13; a ^= (d + c) <<< 18;

Odd-numbered rounds apply QR(a, b, c, d) to each of the four columns in the 4×4 matrix, and even-numbered rounds apply it to each of the four rows. Two consecutive rounds (column-round and row-round) together are called a double-round:

// Odd round QR( 0, 4, 8, 12) // column 1 QR( 5, 9, 13, 1) // column 2 QR(10, 14, 2, 6) // column 3 QR(15, 3, 7, 11) // column 4 // Even round QR( 0, 1, 2, 3) // row 1 QR( 5, 6, 7, 4) // row 2 QR(10, 11, 8, 9) // row 3 QR(15, 12, 13, 14) // row 4

An implementation in C/C++ appears below.

#include <stdint.h>

#define ROTL(a,b) (((a) << (b)) | ((a) >> (32 - (b))))

#define QR(a, b, c, d)( \

b ^= ROTL(a + d, 7), \

c ^= ROTL(b + a, 9), \

d ^= ROTL(c + b,13), \

a ^= ROTL(d + c,18))

#define ROUNDS 20

void salsa20_block(uint32_t out[16], uint32_t const in[16])

{

int i;

uint32_t x[16];

for (i = 0; i < 16; ++i)

x[i] = in[i];

// 10 loops × 2 rounds/loop = 20 rounds

for (i = 0; i < ROUNDS; i += 2) {

// Odd round

QR(x[ 0], x[ 4], x[ 8], x[12]); // column 1

QR(x[ 5], x[ 9], x[13], x[ 1]); // column 2

QR(x[10], x[14], x[ 2], x[ 6]); // column 3

QR(x[15], x[ 3], x[ 7], x[11]); // column 4

// Even round

QR(x[ 0], x[ 1], x[ 2], x[ 3]); // row 1

QR(x[ 5], x[ 6], x[ 7], x[ 4]); // row 2

QR(x[10], x[11], x[ 8], x[ 9]); // row 3

QR(x[15], x[12], x[13], x[14]); // row 4

}

for (i = 0; i < 16; ++i)

out[i] = x[i] + in[i];

}

In the last line, the mixed array is added, word by word, to the original array to obtain its 64-byte key stream block. This is important because the mixing rounds on their own are invertible. In other words, applying the reverse operations would produce the original 4×4 matrix, including the key. Adding the mixed array to the original makes it impossible to recover the input. (This same technique is widely used in hash functions from MD4 through SHA-2.)

Salsa20 performs 20 rounds of mixing on its input.[1] However, reduced-round variants Salsa20/8 and Salsa20/12 using 8 and 12 rounds respectively have also been introduced. These variants were introduced to complement the original Salsa20, not to replace it, and perform better[note 1] in the eSTREAM benchmarks than Salsa20, though with a correspondingly lower security margin.

XSalsa20 with 192-bit nonce

[edit]In 2008, Bernstein proposed a variant of Salsa20 with 192-bit nonces called XSalsa20.[7][8][9] XSalsa20 is provably secure if Salsa20 is secure, but is more suitable for applications where longer nonces are desired. XSalsa20 feeds the key and the first 128 bits of the nonce into one block of Salsa20 (without the final addition, which may either be omitted, or subtracted after a standard Salsa20 block), and uses 256 bits of the output as the key for standard Salsa20 using the last 64 bits of the nonce and the stream position. Specifically, the 256 bits of output used are those corresponding to the non-secret portions of the input: indexes 0, 5, 10, 15, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

eSTREAM selection of Salsa20

[edit]Salsa20/12 has been selected as a Phase 3 design for Profile 1 (software) by the eSTREAM project, receiving the highest weighted voting score of any Profile 1 algorithm at the end of Phase 2.[10] Salsa20 had previously been selected as a Phase 2 Focus design for Profile 1 (software) and as a Phase 2 design for Profile 2 (hardware) by the eSTREAM project,[11] but was not advanced to Phase 3 for Profile 2 because eSTREAM felt that it was probably not a good candidate for extremely resource-constrained hardware environments.[12]

The eSTREAM committee recommends the use of Salsa20/12, the 12-round variant, for "combining very good performance with a comfortable margin of security."[13]

Cryptanalysis of Salsa20

[edit]As of 2015[update], there are no published attacks on Salsa20/12 or the full Salsa20/20; the best attack known[3] breaks 8 of the 12 or 20 rounds.

In 2005, Paul Crowley reported an attack on Salsa20/5 with an estimated time complexity of 2165 and won Bernstein's US$1000 prize for "most interesting Salsa20 cryptanalysis".[14] This attack and all subsequent attacks are based on truncated differential cryptanalysis. In 2006, Fischer, Meier, Berbain, Biasse, and Robshaw reported an attack on Salsa20/6 with estimated time complexity of 2177, and a related-key attack on Salsa20/7 with estimated time complexity of 2217.[15]

In 2007, Tsunoo et al. announced a cryptanalysis of Salsa20 which breaks 8 out of 20 rounds to recover the 256-bit secret key in 2255 operations, using 211.37 keystream pairs.[16] However, this attack does not seem to be competitive with the brute force attack.

In 2008, Aumasson, Fischer, Khazaei, Meier, and Rechberger reported a cryptanalytic attack against Salsa20/7 with a time complexity of 2151, and they reported an attack against Salsa20/8 with an estimated time complexity of 2251. This attack makes use of the new concept of probabilistic neutral key bits for probabilistic detection of a truncated differential. The attack can be adapted to break Salsa20/7 with a 128-bit key.[3]

In 2012, the attack by Aumasson et al. was improved by Shi et al. against Salsa20/7 (128-bit key) to a time complexity of 2109 and Salsa20/8 (256-bit key) to 2250.[17]

In 2013, Mouha and Preneel published a proof[18] that 15 rounds of Salsa20 was 128-bit secure against differential cryptanalysis. (Specifically, it has no differential characteristic with higher probability than 2−130, so differential cryptanalysis would be more difficult than 128-bit key exhaustion.)

In 2025, Dey et al. reported a cryptanalytic attack against Salsa20/8 with a time complexity of 2245.84 and data amounting to 299.47.[19]

ChaCha variant

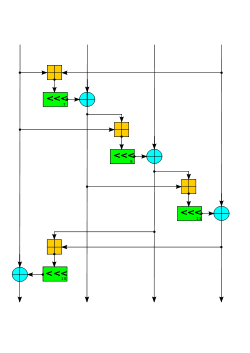

[edit] The ChaCha quarter-round function. Four parallel copies make a round. | |

| General | |

|---|---|

| Designers | Daniel J. Bernstein |

| First published | 2008 |

| Derived from | Salsa20 |

| Related to | Rumba20 |

| Cipher detail | |

| Key sizes | 128 or 256 bits |

| State size | 512 bits |

| Structure | ARX |

| Rounds | 20 |

| Speed | 3.95 cpb on an Intel Core 2 Duo[4]: 2 |

In 2008, Bernstein published the closely related ChaCha family of ciphers, which aim to increase the diffusion per round while achieving the same or slightly better performance.[20] The Aumasson et al. paper also attacks ChaCha, achieving one round fewer (for 256-bit ChaCha6 with complexity 2139, ChaCha7 with complexity 2248, and 128-bit ChaCha6 within 2107) but claims that the attack fails to break 128-bit ChaCha7.[3]

Like Salsa20, ChaCha's initial state includes a 128-bit constant, a 256-bit key, a 64-bit counter, and a 64-bit nonce (in the original version; as described later, a version of ChaCha from RFC 7539 is slightly different), arranged as a 4×4 matrix of 32-bit words.[20] But ChaCha re-arranges some of the words in the initial state:

| "expa" | "nd 3" | "2-by" | "te k" |

| Key | Key | Key | Key |

| Key | Key | Key | Key |

| Counter | Counter | Nonce | Nonce |

The constant is the same as Salsa20 ("expand 32-byte k"). ChaCha replaces the Salsa20 quarter-round QR(a, b, c, d) with:

a += b; d ^= a; d <<<= 16; c += d; b ^= c; b <<<= 12; a += b; d ^= a; d <<<= 8; c += d; b ^= c; b <<<= 7;

Notice that this version updates each word twice, while Salsa20's quarter round updates each word only once. In addition, the ChaCha quarter-round diffuses changes more quickly. On average, after changing 1 input bit the Salsa20 quarter-round will change 8 output bits while ChaCha will change 12.5 output bits.[4]

The ChaCha quarter round has the same number of adds, xors, and bit rotates as the Salsa20 quarter-round, but the fact that two of the rotates are multiples of 8 allows for a small optimization on some architectures including x86.[21] Additionally, the input formatting has been rearranged to support an efficient SSE implementation optimization discovered for Salsa20. Rather than alternating rounds down columns and across rows, they are performed down columns and along diagonals.[4]: 4 Like Salsa20, ChaCha arranges the sixteen 32-bit words in a 4×4 matrix. If we index the matrix elements from 0 to 15

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

then a double round in ChaCha is:

// Odd round QR(0, 4, 8, 12) // column 1 QR(1, 5, 9, 13) // column 2 QR(2, 6, 10, 14) // column 3 QR(3, 7, 11, 15) // column 4 // Even round QR(0, 5, 10, 15) // diagonal 1 (main diagonal) QR(1, 6, 11, 12) // diagonal 2 QR(2, 7, 8, 13) // diagonal 3 QR(3, 4, 9, 14) // diagonal 4

ChaCha20 uses 10 iterations of the double round.[22] An implementation in C/C++ appears below.

#include <stdint.h>

#define ROTL(a,b) (((a) << (b)) | ((a) >> (32 - (b))))

#define QR(a, b, c, d) ( \

a += b, d ^= a, d = ROTL(d, 16), \

c += d, b ^= c, b = ROTL(b, 12), \

a += b, d ^= a, d = ROTL(d, 8), \

c += d, b ^= c, b = ROTL(b, 7))

#define ROUNDS 20

void chacha_block(uint32_t out[16], uint32_t const in[16])

{

int i;

uint32_t x[16];

for (i = 0; i < 16; ++i)

x[i] = in[i];

// 10 loops × 2 rounds/loop = 20 rounds

for (i = 0; i < ROUNDS; i += 2) {

// Odd round

QR(x[0], x[4], x[ 8], x[12]); // column 1

QR(x[1], x[5], x[ 9], x[13]); // column 2

QR(x[2], x[6], x[10], x[14]); // column 3

QR(x[3], x[7], x[11], x[15]); // column 4

// Even round

QR(x[0], x[5], x[10], x[15]); // diagonal 1 (main diagonal)

QR(x[1], x[6], x[11], x[12]); // diagonal 2

QR(x[2], x[7], x[ 8], x[13]); // diagonal 3

QR(x[3], x[4], x[ 9], x[14]); // diagonal 4

}

for (i = 0; i < 16; ++i)

out[i] = x[i] + in[i];

}

ChaCha is the basis of the BLAKE hash function, a finalist in the NIST hash function competition, and its faster successors BLAKE2 and BLAKE3. It also defines a variant using sixteen 64-bit words (1024 bits of state), with correspondingly adjusted rotation constants.

XChaCha

[edit]Although not announced by Bernstein, the security proof of XSalsa20 extends straightforwardly to an analogous XChaCha cipher. Use the key and the first 128 bits of the nonce (in input words 12 through 15) to form a ChaCha input block, then perform the block operation (omitting the final addition). Output words 0–3 and 12–15 (those words corresponding to non-key words of the input) then form the key used for ordinary ChaCha (with the last 64 bits of nonce and 64 bits of block counter).[23]

Reduced-round ChaCha

[edit]Aumasson argues in 2020 that 8 rounds of ChaCha (ChaCha8) probably provides enough resistance to future cryptanalysis for the same security level, yielding a 2.5× speedup.[24] A compromise ChaCha12 (based on the eSTREAM recommendation of a 12-round Salsa)[25] also sees some use.[26] The eSTREAM benchmarking suite includes ChaCha8 and ChaCha12.[20]

ChaCha20 adoption

[edit]Google had selected ChaCha20 along with Bernstein's Poly1305 message authentication code in SPDY, which was intended as a replacement for TLS over TCP.[27] In the process, they proposed a new authenticated encryption construction combining both algorithms, which is called ChaCha20-Poly1305. ChaCha20 and Poly1305 are now used in the QUIC protocol, which replaces SPDY and is used by HTTP/3.[28][29]

Shortly after Google's adoption for TLS, both the ChaCha20 and Poly1305 algorithms were also used for a new chacha20-poly1305@openssh.com cipher in OpenSSH.[30][31] Subsequently, this made it possible for OpenSSH to avoid any dependency on OpenSSL, via a compile-time option.[32]

ChaCha20 is also used for the arc4random random number generator in FreeBSD,[33] OpenBSD,[34] and NetBSD[35] operating systems, instead of the broken RC4, and in DragonFly BSD[36] for the CSPRNG subroutine of the kernel.[37][38] Starting from version 4.8, the Linux kernel uses the ChaCha20 algorithm to generate data for the nonblocking /dev/urandom device.[39][40][41] ChaCha8 is used for the default PRNG in Golang.[42] Rust's CSPRNG uses ChaCha12.[25]

ChaCha20 usually offers better performance than the more prevalent Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) algorithm on systems where the CPU does not feature AES acceleration (such as the AES instruction set for x86 processors). As a result, ChaCha20 is sometimes preferred over AES in certain use cases involving mobile devices, which mostly use ARM-based CPUs.[43][44] Specialized hardware accelerators for ChaCha20 are also less complex compared to AES accelerators.[45]

ChaCha20-Poly1305 (IETF version; see below) is the exclusive algorithm used by the WireGuard VPN system, as of protocol version 1.[46]

Adiantum (cipher) uses XChaCha12.[47]

Internet standards

[edit]An implementation reference for ChaCha20 has been published in RFC 7539. The IETF's implementation modified Bernstein's published algorithm by changing the 64-bit nonce and 64-bit block counter to a 96-bit nonce and 32-bit block counter.[48] The name was not changed when the algorithm was modified, as it is cryptographically insignificant (both form what a cryptographer would recognize as a 128-bit nonce), but the interface change could be a source of confusion for developers. Because of the reduced block counter, the maximum message length that can be safely encrypted by the IETF's variant is 232 blocks of 64 bytes (256 GiB). For applications where this is not enough, such as file or disk encryption, RFC 7539 proposes using the original algorithm with 64-bit nonce.

| "expa" | "nd 3" | "2-by" | "te k" |

| Key | Key | Key | Key |

| Key | Key | Key | Key |

| Counter | Nonce | Nonce | Nonce |

Use of ChaCha20 in IKE and IPsec has been standardized in RFC 7634. Standardization of its use in TLS is published in RFC 7905.

In 2018, RFC 7539 was obsoleted by RFC 8439. RFC 8439 merges in some errata and adds additional security considerations.[49]

See also

[edit]- Speck – an add-rotate-xor cipher developed by the NSA

- ChaCha20-Poly1305 – an AEAD scheme combining ChaCha20 with the Poly1305 MAC

Notes

[edit]- ^ Since the majority of the work consists of performing the repeated rounds, the number of rounds is inversely proportional to the performance. That is, halving the number of rounds roughly doubles the performance. Reduced-round variants are thus appreciably faster.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Daniel J. Bernstein (2007-12-24). "The Salsa20 family of stream ciphers" (PDF). cr.yp.to.

- ^ Daniel J. Bernstein (2013-05-16). "Salsa 20 speed; Salsa20 software".

- ^ a b c d Jean-Philippe Aumasson; Simon Fischer; Shahram Khazaei; Willi Meier; Christian Rechberger (2008-03-14). "New Features of Latin Dances" (PDF). International Association for Cryptologic Research.

- ^ a b c d Bernstein, Daniel (28 January 2008), ChaCha, a variant of Salsa20 (PDF), retrieved 2018-06-03

- ^ Daniel J. Bernstein (2013-05-16). "Snuffle 2005: the Salsa20 encryption function".

- ^ "Salsa20: Software speed". 2007-05-11.

- ^ Daniel J. Bernstein. "Extending the Salsa20 nonce (updated in 2011)" (PDF). cr.yp.to. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ^ Daniel J. Bernstein. "Extending the Salsa20 nonce (original version)" (PDF). cr.yp.to. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ^ "Salsa20/12". ECRYPT II. Archived from the original on 2018-02-26. Retrieved 2017-08-22.

- ^ "The eSTREAM Project: End of Phase 2". eSTREAM. 2008-04-29. Archived from the original on 2016-07-09. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ Hongjun Wu (2007-03-30). "eSTREAM PHASE 3: End of Phase 1". eSTREAM. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2006-03-30.

- ^ "eSTREAM: Short Report on the End of the Second Phase" (PDF). eSTREAM. 2007-03-26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-09. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ "Salsa20/12, The eSTREAM portfolio page". www.ecrypt.eu.org.

- ^ Paul Crowley (2006-02-09). "Truncated differential cryptanalysis of five rounds of Salsa20".

- ^ Simon Fischer; Willi Meier; Côme Berbain; Jean-François Biasse; M. J. B. Robshaw (2006). "Non-randomness in eSTREAM Candidates Salsa20 and TSC-4". Progress in Cryptology - INDOCRYPT 2006: 7th International Conference on Cryptology in India, Kolkata, India, December 11-13, 2006, Proceeding. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 4329. pp. 2–16. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.121.7248. doi:10.1007/11941378_2. ISBN 978-3-540-49767-7.

- ^ Yukiyasu Tsunoo; Teruo Saito; Hiroyasu Kubo; Tomoyasu Suzaki; Hiroki Nakashima (2007-01-02). "Differential Cryptanalysis of Salsa20/8" (PDF). ECRYPT. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ Zhenqing Shi; Bin Zhang; Dengguo Feng; Wenling Wu (2012). "Improved Key Recovery Attacks on Reduced-Round Salsa20 and ChaCha". Information Security and Cryptology – ICISC 2012. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 7839. pp. 337–351. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-37682-5_24. ISBN 978-3-642-37681-8.

- ^ Nicky Mouha; Bart Preneel (2013). "Towards Finding Optimal Differential Characteristics for ARX: Application to Salsa20" (PDF). International Association for Cryptologic Research.

- ^ Dey, Sabyasachi; Maitra, Subhamoy; Sarkar, Santanu; Sharma, Nitin Kumar (2025). "Significantly Improved Cryptanalysis of Salsa20 With Two-Round Criteria". Cryptology ePrint Archive.

- ^ a b c Daniel J. Bernstein (2008-04-25). "The ChaCha family of stream ciphers".

- ^ Neves, Samuel (2009-10-07), Faster ChaCha implementations for Intel processors, archived from the original on 2017-03-28, retrieved 2016-09-07,

two of these constants are multiples of 8; this allows for a 1 instruction rotation in Core2 and later Intel CPUs using the pshufb instruction

- ^ Y. Nir; A. Langley (May 2015). "ChaCha20 and Poly1305 for IETF Protocols: RFC 7539".

- ^ Arciszewski, Scott (10 January 2020). "XChaCha: eXtended-nonce ChaCha and AEAD_XChaCha20_Poly1305 (Expired Internet-Draft)". Ietf Datatracker.

- ^ Aumasson, Jean-Philippe (2020). Too Much Crypto (PDF). Real World Crypto Symposium.

- ^ a b "rand_chacha: consider ChaCha12 (or possibly ChaCha8) over ChaCha20 · Issue #932 · rust-random/rand". GitHub.

- ^ "ChaCha". Cryptography Primer.

- ^ "Do the ChaCha: better mobile performance with cryptography". The Cloudflare Blog. 2015-02-23. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Thomson, Martin; Turner, Sean (May 2021). "RFC 9001". datatracker.ietf.org. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Bishop, Mike (2 February 2021). "draft: IETF QUIC HTTP". datatracker.ietf.org. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Miller, Damien (2016-05-03). "ssh/PROTOCOL.chacha20poly1305". Super User's BSD Cross Reference: PROTOCOL.chacha20poly1305. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ Murenin, Constantine A. (2013-12-11). Unknown Lamer (ed.). "OpenSSH Has a New Cipher — Chacha20-poly1305 — from D.J. Bernstein". Slashdot. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ Murenin, Constantine A. (2014-04-30). Soulskill (ed.). "OpenSSH No Longer Has To Depend On OpenSSL". Slashdot. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ "Revision 317015". 2017-04-16. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

Replace the RC4 algorithm for generating in-kernel secure random numbers with Chacha20

- ^ guenther (Philip Guenther), ed. (2015-09-13). "libc/crypt/arc4random.c". Super User's BSD Cross Reference: arc4random.c. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

ChaCha based random number generator for OpenBSD.

- ^ riastradh (Taylor Campbell), ed. (2016-03-25). "libc/gen/arc4random.c". Super User's BSD Cross Reference: arc4random.c. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

Legacy arc4random(3) API from OpenBSD reimplemented using the ChaCha20 PRF, with per-thread state.

- ^ "kern/subr_csprng.c". Super User's BSD Cross Reference: subr_csprng.c. 2015-11-04. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

chacha_encrypt_bytes - ^ "ChaCha Usage & Deployment". 2016-09-07. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ "arc4random(3)". NetBSD Manual Pages. 2014-11-16. Archived from the original on 2020-07-06. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ Corbet, Jonathan. "Replacing /dev/urandom". Linux Weekly News. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

- ^ "Merge tag 'random_for_linus' of git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/tytso/random". Linux kernel source tree. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

random: replace non-blocking pool with a Chacha20-based CRNG

- ^ Michael Larabel (2016-07-25). "/dev/random Seeing Improvements For Linux 4.8". Phoronix. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ^ Cox, Russ; Valsorda, Filippo. "Secure Randomness in Go 1.22 - The Go Programming Language". go.dev.

- ^ "What's the appeal of using ChaCha20 instead of AES?". Cryptography Stack Exchange. 2016-04-12.

- ^ "AES-NI SSL Performance Study @ Calomel.org".

- ^ Pfau, Johannes; Reuter, Maximilian; Harbaum, Tanja; Hofmann, Klaus; Becker, Jurgen (September 2019). "A Hardware Perspective on the ChaCha Ciphers: Scalable Chacha8/12/20 Implementations Ranging from 476 Slices to Bitrates of 175 Gbit/s". 2019 32nd IEEE International System-on-Chip Conference (SOCC). pp. 294–299. doi:10.1109/SOCC46988.2019.1570548289. ISBN 978-1-7281-3483-3.

- ^ "Protocol and Cryptography". WireGuard. Jason A. Donenfeld. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ Edge, Jake (16 January 2019). "Adiantum: encryption for the low end". LWN.net.

- ^ a b "ChaCha20 and Poly1305 for IETF protocols" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-08-07.

Changes from regular ChaCha. The nonce: block sequence number split was changed from 64:64 to 96:32 [...] The ChaCha20 state is initialized as follows:

- ^ Header of RFC 7539.

External links

[edit]- Snuffle 2005: the Salsa20 encryption function

- Salsa20 specification (PDF)

- Salsa20/8 and Salsa20/12 (PDF)

- The eSTREAM Project: Salsa20 Archived 2022-08-18 at the Wayback Machine

- The ChaCha family of stream ciphers

- Salsa20 Usage & Deployment

- Implementation and Didactical Visualization of the ChaCha Cipher Family in CrypTool 2

- ChaCha20 Demo in Excel Example implementation and demonstration in Excel (without macros) by Tim Wambach

Salsa20

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Origins and Designer

Salsa20 was designed by Daniel J. Bernstein, a prominent cryptographer known for his work on secure and efficient cryptographic primitives. As a refinement of his earlier Salsa10 design from November 2004, development of Salsa20 began in late 2004 or early 2005. Motivated by vulnerabilities in existing ciphers like AES, particularly susceptibility to cache-timing attacks that could leak keys through side-channel analysis, Bernstein sought to create a stream cipher that inherently resisted such threats by avoiding lookup tables and relying on simple arithmetic operations.[3][1] The core was introduced in March 2005, with the initial specification released in April 2005. Salsa20, initially referred to as Snuffle 2005, was first presented at the Symmetric Key Encryption Workshop (SKEW) in Aarhus, Denmark, on May 26–27, 2005, where early discussions occurred. To encourage scrutiny, Bernstein offered a $1000 prize for the best cryptanalytic results by the end of 2005, which was awarded to Paul Crowley for his truncated differential attack on a reduced-round version (five rounds).[4][5] The full specification of the Salsa20 family was detailed in a 2007 technical report, following its initial submission to the eSTREAM project in April 2005.[1] The primary goals of Salsa20's design emphasized simplicity to facilitate security auditing, high-speed performance across diverse hardware platforms including embedded systems, and a substantial security margin exceeding that of block ciphers like AES, achieved through a 20-round core function providing 256-bit security.[1][4] These objectives positioned Salsa20 as a practical alternative for software-based encryption, prioritizing verifiable security over complexity while outperforming AES in cycle counts per byte on processors like ARM and x86.[1]Initial Publication and Goals

Salsa20 was first introduced by Daniel J. Bernstein in 2005 as a candidate stream cipher for the eSTREAM project, with an initial presentation at the Symmetric Key Encryption Workshop (SKEW) that year, where early cryptanalytic results were also discussed.[1][5] The design, originally termed Snuffle 2005, was detailed in an initial specification document released in April 2005, emphasizing its role as a high-performance alternative to existing stream ciphers.[6] A comprehensive specification for the Salsa20 family appeared in Bernstein's paper presented at Fast Software Encryption (FSE) 2008, which formalized the cipher's structure and variants.[1][7] The primary goals of Salsa20 were to achieve strong security margins while prioritizing software efficiency on general-purpose processors, without relying on specialized hardware accelerations such as table lookups or custom instructions.[1] To this end, the cipher employs 20 rounds of mixing in its core variant (Salsa20/20), selected to provide robust resistance against known attacks, with the fastest practical attack limited to a full 256-bit brute-force search.[1] It supports a 256-bit key size for high security, generates 64-byte (512-bit) output blocks from a key, 64-bit nonce, and 64-bit block counter, and uses only Addition, Rotation, and XOR (ARX) operations on 32-bit words to ensure simplicity, auditability, and resistance to timing attacks.[1][8] This design philosophy explicitly addressed shortcomings in contemporaries like RC4, which suffered from key-dependent biases and vulnerability to state recovery attacks, by avoiding data-dependent branches and substitution tables that could introduce side-channel leaks or analytical weaknesses.[1] Instead, Salsa20's ARX-based construction facilitates provable diffusion properties and uniform performance, achieving approximately 4 cycles per byte on contemporary CPUs for the 20-round version, making it suitable for resource-constrained software environments.[1]Core Algorithm

State Initialization

Salsa20 initializes its internal state as a 512-bit (64-byte) block, consisting of 16 32-bit words arranged in a 4×4 matrix. This state serves as the foundation for the core mixing operations and is derived from a 256-bit key (eight 32-bit words), a 64-bit nonce (two 32-bit words), a 64-bit block counter (two 32-bit words, initialized to zero for the first block), and four fixed 32-bit constant words derived from the ASCII string "expand 32-byte k" interpreted in little-endian byte order.[1] The constant words, often denoted as σ (sigma), are placed at specific positions in the state array: σ₀ = 0x61707865 ("expa"), σ₁ = 0x3320646e ("nd 3"), σ₂ = 0x79622d32 ("2-by"), and σ₃ = 0x6b206574 ("te k"). These constants occupy positions 0, 5, 10, and 15 in the linear 16-word array, corresponding to the main diagonal of the 4×4 matrix. The key words are split across the state: the first four key words (k₀ to k₃) occupy positions 1 through 4, and the remaining four (k₄ to k₇) occupy positions 11 through 14. The nonce words (n₀ and n₁) are placed at positions 6 and 7, while the block counter words (c₀ = 0 and c₁ = 0 initially) are at positions 8 and 9.[1] The resulting initial state array can be expressed as:state[0] = σ₀

state[1] = k₀

state[2] = k₁

state[3] = k₂

state[4] = k₃

state[5] = σ₁

state[6] = n₀

state[7] = n₁

state[8] = c₀ (0)

state[9] = c₁ (0)

state[10] = σ₂

state[11] = k₄

state[12] = k₅

state[13] = k₆

state[14] = k₇

state[15] = σ₃

state[0] = σ₀

state[1] = k₀

state[2] = k₁

state[3] = k₂

state[4] = k₃

state[5] = σ₁

state[6] = n₀

state[7] = n₁

state[8] = c₀ (0)

state[9] = c₁ (0)

state[10] = σ₂

state[11] = k₄

state[12] = k₅

state[13] = k₆

state[14] = k₇

state[15] = σ₃

| Column 0 | Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row 0 | σ₀ | k₀ | k₁ | k₂ |

| Row 1 | k₃ | σ₁ | n₀ | n₁ |

| Row 2 | c₀ (0) | c₁ (0) | σ₂ | k₄ |

| Row 3 | k₅ | k₆ | k₇ | σ₃ |

Quarter-Round Function

The quarter-round (QR) function serves as the fundamental nonlinear primitive in Salsa20, operating on four 32-bit little-endian words denoted as , , , and , to provide diffusion and mixing within the cipher's state.[1] This function combines addition modulo , bitwise XOR, and fixed left rotations, forming an ARX (Addition-Rotation-XOR) construction that ensures constant-time execution without reliance on table lookups or S-boxes, thereby mitigating timing attacks and enabling efficient implementation across hardware platforms.[1] The quarter-round proceeds through a fixed sequence of eight operations, updating the inputs in place: These steps leverage the algebraic properties of XOR and modular addition to scramble the word values, with the rotations (7, 9, 13, and 18 bits) chosen to distribute bits effectively across the 32-bit words.[1] In the Salsa20 state, represented as a 4×4 matrix of 32-bit words, the quarter-round is applied separately to the four words of each row during the row-round phase, followed by application to the four words of each column in the column-round phase, ensuring thorough intermixing between matrix dimensions without explicit transposition.[1] This row-and-column application pattern repeats across multiple rounds, with the quarter-round providing the core nonlinearity that prevents linear attacks and promotes avalanche effects in the output keystream.[1]Core Mixing Rounds

The core mixing rounds in Salsa20 form the heart of its hash function, which operates on a 16-word (512-bit) state represented as a 4x4 matrix of 32-bit words. These rounds apply the quarter-round function systematically to achieve rapid diffusion across the entire state, ensuring that changes in any input word propagate to all output words after a few iterations. The process consists of 20 rounds, grouped into 10 double-rounds, where each double-round alternates between row-wise and column-wise applications of the quarter-round to mix the state thoroughly.[9] A double-round begins with a row-round, applying the quarter-round function to each of the four rows in the 4x4 state matrix, followed by a column-round that applies it to each of the four columns. This alternation ensures orthogonal mixing: the row-round diffuses data horizontally, while the column-round diffuses it vertically, promoting avalanche effects where a single-bit change affects approximately half the output bits per round. The odd-numbered rounds (3, 5, ..., 19) specifically follow row-wise mixing with column-wise operations, maintaining the pattern of horizontal-then-vertical diffusion throughout the 10 double-rounds. This structure, with 8 quarter-rounds per double-round (4 rows + 4 columns), totals 80 quarter-round invocations over 20 rounds, providing strong nonlinear mixing without relying on S-boxes.[9] After the final double-round, the output is computed by adding the initial state to the fully mixed state, with all operations performed modulo on each 32-bit word. This serialization step, known as the "finalization," leverages the modular arithmetic to wrap around values and complete the diffusion, producing a 64-byte output block from the 64-byte input state. The addition ensures that the output retains properties of the input while incorporating the chaotic mixing from the rounds, contributing to Salsa20's resistance to differential attacks.[9] The round structure can be illustrated in pseudocode as follows, emphasizing the iterative application and diffusion:function salsa20_core(input_state[16]):

state = copy(input_state) // 4x4 matrix of 32-bit words

for round in 0 to 19: // 20 rounds total

if round % 2 == 0: // Even rounds: row-round

for i in 0 to 3:

quarter_round(state[0+i], state[1+i], state[2+i], state[3+i])

else: // Odd rounds: column-round

for i in 0 to 3:

quarter_round(state[0*4+i], state[1*4+i], state[2*4+i], state[3*4+i])

output = [0]*16

for i in 0 to 15:

output[i] = (state[i] + input_state[i]) mod 2^32

return output // As 64-byte little-endian block

function salsa20_core(input_state[16]):

state = copy(input_state) // 4x4 matrix of 32-bit words

for round in 0 to 19: // 20 rounds total

if round % 2 == 0: // Even rounds: row-round

for i in 0 to 3:

quarter_round(state[0+i], state[1+i], state[2+i], state[3+i])

else: // Odd rounds: column-round

for i in 0 to 3:

quarter_round(state[0*4+i], state[1*4+i], state[2*4+i], state[3*4+i])

output = [0]*16

for i in 0 to 15:

output[i] = (state[i] + input_state[i]) mod 2^32

return output // As 64-byte little-endian block