Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chain complex

View on WikipediaIn mathematics, a chain complex is an algebraic structure that consists of a sequence of abelian groups (or modules) and a sequence of homomorphisms between consecutive groups such that the image of each homomorphism is contained in the kernel of the next. Associated to a chain complex is its homology, which is (loosely speaking) a measure of the failure of a chain complex to be exact.

A cochain complex is similar to a chain complex, except that its homomorphisms are in the opposite direction. The homology of a cochain complex is called its cohomology.

In algebraic topology, the singular chain complex of a topological space X is constructed using continuous maps from a simplex to X, and the homomorphisms of the chain complex capture how these maps restrict to the boundary of the simplex. The homology of this chain complex is called the singular homology of X, and is a commonly used invariant of a topological space.

Chain complexes are studied in homological algebra, but are used in several areas of mathematics, including abstract algebra, Galois theory, differential geometry and algebraic geometry. They can be defined more generally in abelian categories.

Definitions

[edit]A chain complex is a sequence of abelian groups or modules connected by homomorphisms (called boundary operators or differentials) , such that the composition of any two consecutive maps is the zero map. Explicitly, the differentials satisfy for all , or, concisely, . The complex may be written out as follows:

The cochain complex is the dual notion to a chain complex. It consists of a sequence of abelian groups or modules connected by homomorphisms (coboundary operators) satisfying . The cochain complex may be written out in a similar fashion to the chain complex:

In both cases, the index is referred to as the degree (or dimension). The difference between chain and cochain complexes is that, in chain complexes, the differentials decrease dimension, whereas in cochain complexes they increase dimension. All the concepts and definitions for chain complexes apply to cochain complexes, except that they will follow this different convention for dimension, and often terms will be given the prefix co-. In this article, definitions will be given for chain complexes when the distinction is not required.

A bounded chain complex is one in which almost all the are 0; that is, a finite complex extended to the left and right by 0. An example is the chain complex defining the simplicial homology of a finite simplicial complex. A chain complex is bounded above if all modules above some fixed degree are 0, and is bounded below if all modules below some fixed degree are 0. Clearly, a complex is bounded both above and below if and only if the complex is bounded.

The elements of the individual groups of a (co)chain complex are called (co)chains. The elements in the kernel of are called (co)cycles (or closed elements), and the elements in the image of d are called (co)boundaries (or exact elements). Right from the definition of the differential, all boundaries are cycles. The n-th (co)homology group Hn (Hn) is the group of (co)cycles modulo (co)boundaries in degree n, that is,

Exact sequences

[edit]An exact sequence (or exact complex) is a chain complex whose homology groups are all zero. This means all closed elements in the complex are exact. A short exact sequence is a bounded exact sequence in which only the groups Ak, Ak+1, Ak+2 may be nonzero. For example, the following chain complex is a short exact sequence.

In the middle group, the closed elements are the elements pZ; these are clearly the exact elements in this group.

Chain maps

[edit]A chain map f between two chain complexes and is a sequence of homomorphisms for each n that commutes with the boundary operators on the two chain complexes, so . This is written out in the following commutative diagram.

A chain map sends cycles to cycles and boundaries to boundaries, and thus induces a map on homology .

A continuous map f between topological spaces X and Y induces a chain map between the singular chain complexes of X and Y, and hence induces a map f* between the singular homology of X and Y as well. When X and Y are both equal to the n-sphere, the map induced on homology defines the degree of the map f.

The concept of chain map reduces to the one of boundary through the construction of the cone of a chain map.

Chain homotopy

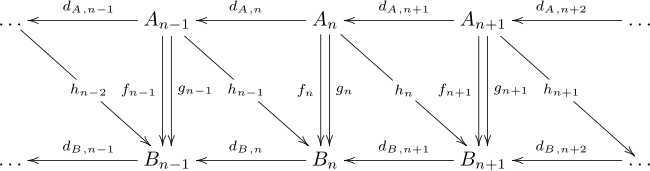

[edit]A chain homotopy offers a way to relate two chain maps that induce the same map on homology groups, even though the maps may be different. Given two chain complexes A and B, and two chain maps f, g : A → B, a chain homotopy is a sequence of homomorphisms hn : An → Bn+1 such that hdA + dBh = f − g. The maps may be written out in a diagram as follows, but this diagram is not commutative.

The map hdA + dBh is easily verified to induce the zero map on homology, for any h. It immediately follows that f and g induce the same map on homology. One says f and g are chain homotopic (or simply homotopic), and this property defines an equivalence relation between chain maps.

Let X and Y be topological spaces. In the case of singular homology, a homotopy between continuous maps f, g : X → Y induces a chain homotopy between the chain maps corresponding to f and g. This shows that two homotopic maps induce the same map on singular homology. The name "chain homotopy" is motivated by this example.

Examples

[edit]Singular homology

[edit]Let X be a topological space. Define Cn(X) for natural n to be the free abelian group formally generated by singular n-simplices in X, and define the boundary map to be

where the hat denotes the omission of a vertex. That is, the boundary of a singular simplex is the alternating sum of restrictions to its faces. It can be shown that ∂2 = 0, so is a chain complex; the singular homology is the homology of this complex.

Singular homology is a useful invariant of topological spaces up to homotopy equivalence. The degree zero homology group is a free abelian group on the path-components of X.

de Rham cohomology

[edit]The differential k-forms on any smooth manifold M form a real vector space called Ωk(M) under addition. The exterior derivative d maps Ωk(M) to Ωk+1(M), and d2 = 0 follows essentially from symmetry of second derivatives, so the vector spaces of k-forms along with the exterior derivative are a cochain complex.

The cohomology of this complex is called the de Rham cohomology of M. Locally constant functions are designated with its isomorphism with c the count of mutually disconnected components of M. This way the complex was extended to leave the complex exact at zero-form level using the subset operator.

Smooth maps between manifolds induce chain maps, and smooth homotopies between maps induce chain homotopies.

Category of chain complexes

[edit]Chain complexes of -modules with chain maps as morphisms form a category , where is a commutative ring.

If and are chain complexes, their tensor product is a chain complex with degree elements given by

and differential given by

where and are any two homogeneous vectors in and respectively, and denotes the degree of .

This tensor product makes the category into a symmetric monoidal category. The identity object with respect to this monoidal product is the base ring viewed as a chain complex in degree . The braiding is given on simple tensors of homogeneous elements by

The sign is necessary for the braiding to be a chain map.

Moreover, the category of chain complexes of -modules also has internal Hom: given chain complexes and , the internal Hom of and , denoted , is the chain complex with degree elements given by and differential given by

- .

We have a natural isomorphism

Further examples

[edit]See also

[edit]- Differential graded algebra

- Differential graded Lie algebra

- Dold–Kan correspondence says there is an equivalence between the category of chain complexes and the category of simplicial abelian groups.

- Buchsbaum–Eisenbud acyclicity criterion

- Differential graded module

References

[edit]- Bott, Raoul; Tu, Loring W. (1982), Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90613-3

- Hatcher, Allen (2002). Algebraic Topology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79540-0.

Chain complex

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Chain complexes

In homological algebra, a chain complex over a ring is a sequence of -modules equipped with boundary homomorphisms satisfying for all .[3] This condition, often denoted , implies that the image of each lies in the kernel of .[4] The complex is typically denoted extending over all integers , with for sufficiently extreme indices in many applications.[3] The underlying graded module is the direct sum .[4] The dual notion is a cochain complex, with modules and coboundary maps satisfying , denoted [3] An augmented chain complex includes a map (or to a target module) satisfying .[3] Exact sequences are chain complexes in which the image of each boundary map equals the kernel of the next.[4]Exact sequences

In homological algebra, an exact sequence of R-modules and homomorphisms is a sequence such that for all .[4][5] For a chain complex , exactness at means .[4] A chain complex is exact if it is exact at every position.[4] A short exact sequence has the form . Exactness implies is injective, is surjective, and , so .[4][5] Homology groups are defined as . A complex is exact if and only if for all , meaning every cycle is a boundary.[4][5] Nonzero homology indicates failure of exactness. For example, the simplicial chain complex of the circle has . The chain complex for the torus has .[4]Morphisms and Equivalences

Chain maps

A chain map between two chain complexes and of -modules is a collection of -module homomorphisms for each integer , satisfying the compatibility condition for all , where and are the boundary maps of and , respectively.[4][3] This condition ensures that the chain map preserves the differential structure, making the following square commutative for each degree: Such maps are denoted .[6] The collection of chain maps forms a category structure on chain complexes. Specifically, if and are chain maps, their composition is defined by , which satisfies the compatibility condition since both and individually do.[4] The identity map on a chain complex is a chain map, serving as the identity morphism.[3] Degree-shifting operations, such as the suspension functor , act on chain complexes while preserving the category of chain maps. The suspension of a complex is defined by with boundary map , where the sign ensures that .[3] A chain map induces a natural chain map via .[7] Kernels and cokernels of chain maps are themselves chain complexes, induced componentwise. The kernel complex has in each degree, with boundary map the restriction of , which is well-defined because the compatibility condition implies maps into .[3] Similarly, the cokernel complex has with induced boundary map, as the compatibility ensures it descends to the quotients. These constructions make the category of chain complexes abelian when -modules form an abelian category.[4]Chain homotopies

A chain homotopy between two chain maps is a family of homomorphisms satisfying for all , where and are the boundary operators of and . This is denoted via . The relation provides an algebraic analogue of homotopy in topology, with differences between maps corrected by boundary terms. In singular chain complexes, such homotopies are often constructed using the prism operator on singular simplices.[4] Two chain complexes are homotopy equivalent if there exist chain maps and such that and . The relation is an equivalence relation on chain maps between fixed complexes. Homotopies compose additively: if via and via , then via , where . Homotopies are also compatible with composition: if via and via , then via (degreewise).[4] A chain map is null-homotopic if , meaning there exists such that for all . Null-homotopic maps induce the zero homomorphism on homology.[4]Quasi-isomorphisms

In homological algebra, a chain map is a quasi-isomorphism if it induces isomorphisms on homology: is an isomorphism for every .[8] Quasi-isomorphisms act as weak equivalences, preserving homology up to isomorphism.[8] They arise in resolutions, acyclic complexes, and comparisons of chain complexes. Examples include:- the augmentation map in a projective resolution of a module , where is acyclic in positive degrees and ;

- a quasi-isomorphism from an acyclic complex (with vanishing homology in all degrees) to the zero complex;

- the inclusion of the simplicial chain complex into the singular chain complex of a simplicial set.[3]

Homology Computation

Homology groups

In algebraic topology, the homology groups of a chain complex are the primary algebraic invariants that capture essential topological information. For a chain complex of abelian groups or modules over a ring , the -cycles are , and the -boundaries are , since .[4] The -th homology group is the quotient which measures cycles that are not boundaries, thereby detecting "holes" of dimension . The full homology is graded as , with most terms typically zero in examples. This construction isolates non-trivial features by quotienting out boundaries, often enabling classification of spaces up to homotopy equivalence. Homology is functorial: a chain map induces homomorphisms by , well-defined because preserves boundaries. Thus, defines a functor from the category of chain complexes over to abelian groups.[4] For chain complexes of finite type over a field, the Euler characteristic is , which equals and is a homotopy invariant. If the complex is exact, meaning for all , then for all .[4]Long exact sequences in homology

A short exact sequence of chain complexes induces a long exact sequence in homology groups: where and are the induced maps on homology, and is the connecting homomorphism.[10][11][12] The connecting homomorphism is defined as follows: for a homology class represented by a cycle $c \in C_n$ with $\partial c = 0$, lift $c$ to some $b \in B_n$ such that $p(b) = c$; then $\partial b$ lies in the image of $i$, so $\partial b = i(a)$ for a unique $a \in A_{n-1}$, and since $i$ is injective and $\partial^2 = 0$, $a$ is a cycle whose class is independent of the choice of lift .[10][11] The proof proceeds degreewise by applying the snake lemma to the short exact sequence of cycles and boundaries in each dimension, establishing exactness at each , , and through diagram chasing to verify that kernels equal images at every step.[12][11] This long exact sequence has applications in detecting non-split extensions, where a nonzero connecting homomorphism implies that the original short exact sequence does not split; it also yields the five-term exact sequence as its initial segment in low dimensions.[10][11] Additionally, the alternating sum property ensures additivity of Euler characteristics: if the complexes are bounded, then , where denotes the Euler characteristic .[13][14]Key Examples

Simplicial and singular chain complexes

In algebraic topology, the simplicial chain complex gives a combinatorial description of the homology of simplicial complexes. For a simplicial complex , the chain group is the free abelian group generated by the oriented -simplices of . The boundary operator is defined on a generator by where denotes omission of the -th vertex. This extends linearly to all of , and follows from cancellation in the telescoping sum of face inclusions.[4] The singular chain complex generalizes this construction to arbitrary topological spaces , without requiring a triangulation. The chain group is the free abelian group generated by continuous maps (singular -simplices), where is the standard geometric -simplex. The boundary operator is where is the inclusion of the -th face. Again, holds by the simplicial identities satisfied by the face maps . An augmentation sends a 0-chain to , enabling reduced homology by adjoining a in degree −1.[4] For a pair with , the relative chain groups are , with induced boundary map. This yields a short exact sequence of chain complexes via inclusion and quotient. As a computational example, the standard -simplex (viewed as a simplicial complex) is contractible, so for and . In relative terms, generated by the class of the identity map on , with for , detecting the fundamental class modulo the boundary.[4]de Rham cochain complexes

The de Rham cochain complex arises in the context of smooth manifolds and provides a differential-geometric realization of cohomology. For a smooth manifold , the de Rham complex is the sequence of spaces of smooth differential forms, where denotes the vector space of smooth -forms on , equipped with the coboundary operator given by the exterior derivative. This operator satisfies , making a cochain complex whose cohomology groups capture topological invariants of .[15][16] Within this complex, the closed -forms are those in the kernel , while the exact -forms form the image . The th de Rham cohomology group is then defined as , which measures the failure of closed forms to be exact and is isomorphic to the singular cohomology of with real coefficients.[16][15] A fundamental property is the Poincaré lemma, which states that if is contractible, then for all , implying that every closed form on such a is exact. This local exactness underpins the computation of de Rham cohomology on more general manifolds via partitions of unity and Mayer-Vietoris sequences.[17] The de Rham complex relates to homology through an integration pairing that defines a nondegenerate bilinear map between de Rham cohomology and singular homology: for a closed -form and a -chain , the integral induces , which is well-defined on cohomology and homology classes and identifies .[18] As an illustrative example, the first de Rham cohomology of the circle is , generated by the cohomology class of the angular 1-form , which is closed but not exact on .[19]Algebraic chain complexes

In homological algebra, algebraic chain complexes are constructed from modules over a commutative ring , often serving as resolutions to compute invariants such as Tor and Ext groups. These complexes consist of -modules equipped with differentials satisfying , and they play a central role in deriving functorial properties without relying on geometric structures.[3] A prominent example is the Koszul complex associated to a ring and elements . This complex has modules , the exterior powers of the free module with basis , and the differential is defined by where the hat denotes omission. The Koszul complex is exact if and only if form a regular sequence in , providing a measure of the depth of the ideal .[20][21] Projective resolutions exemplify algebraic chain complexes used to resolve modules. For an -module , a projective resolution is a chain complex with each projective and , augmented by the map to form an exact sequence . This extends to a full chain complex by setting for , and the homology of the complex ending at vanishes in positive degrees, enabling computations of derived functors.[3] The bar resolution provides a canonical projective resolution for computing Tor and Ext. For an associative algebra over and a right -module , the bar resolution is the complex with terms (where denotes -fold tensor products over ) and differentials alternating sums of face maps that multiply adjacent factors. This resolution is free as an -module complex and is particularly useful for bimodule computations, as its homology yields Tor groups when tensored with another module.[3] The tensor product construction yields new algebraic chain complexes from existing ones. Given two chain complexes and of right and left -modules, respectively, their tensor product carries the differential This "twisted" boundary ensures is a chain complex, and under suitable flatness conditions, its homology is the Tor of the homologies of and .[3] Acyclic algebraic chain complexes, where all homology groups , include contractible ones, which admit a contracting homotopy satisfying . Such complexes are homotopy equivalent to the zero complex and arise naturally in resolutions, ensuring exactness without nontrivial homology.[3]Categorical Framework

Category of chain complexes

The category of chain complexes over a ring , denoted or , has as its objects all chain complexes of -modules and as its morphisms all chain maps between such complexes, with composition of morphisms defined pointwise on each degree. A chain map between complexes and consists of -module homomorphisms for each satisfying , ensuring commutativity of the diagram in each degree. The category is abelian, inheriting its structure from the abelian category -Mod of -modules. Specifically, for a chain map , the kernel is the subcomplex with and induced differential, while the cokernel is the quotient complex with and induced differential; both are computed degreewise. An exact sequence of chain complexes is exact if it is exact in each degree, meaning for all . There exists a forgetful functor that sends a chain complex to the family of its underlying modules , disregarding the differentials. The homology functors , defined by , are functors from the category of chain complexes to -modules. The category possesses a monoidal structure via the tensor product of chain complexes, which defines a bifunctor . For complexes and , the tensor product complex has components , with differential given on by ; this structure is symmetric monoidal when is commutative. Notable full subcategories of include , consisting of non-negatively graded chain complexes (i.e., for ), which is closed under kernels, cokernels, and extensions. Another example is the full subcategory of projective complexes, comprising those chain complexes where each module is a projective -module; this subcategory is useful for resolutions in homological algebra.Functors on chain complexes

In the category of chain complexes of -modules, the homology functor assigns to each complex its th homology group , where . For a chain map , the induced map is defined by , where $$ is the homology class of a cycle . This functor is right exact: a short exact sequence induces exact sequences for each . The tensor product functor is defined componentwise: , with differential . When is a principal ideal domain and consists of free modules, the Künneth theorem yields a short exact sequence This sequence splits (non-naturally) if one set of homology modules is flat over . When is a field, the terms vanish, giving an isomorphism . Proof outline Special case: zero differentialsIf all differentials of are zero, then . The tensor product is . Homology commutes with direct sums, so Since is free and thus flat, tensoring with commutes with homology, yielding Combining these, with no terms appearing due to the freeness of the modules in . General case

For each degree , consider the short exact sequence where and . Since is a PID and is free, submodules are free, and the sequence splits: . This induces a splitting of chain complexes , both with zero differentials. Tensoring with yields a short exact sequence of complexes inducing a long exact sequence in homology. By the special case, The left term of the Künneth sequence is the cokernel of the induced map from boundaries to cycles, . By right exactness of tensor, this cokernel is . The right term arises from the failure of left exactness, measured by . The sequence is a projective resolution of , so Summing over degrees identifies the sum. The Hom functor is defined by , with differential induced by those of and . It is left exact. Derived functors capture exactness failures: the left derived functors are the homology of the tensor product after projective resolution of the first argument, while the right derived functors are the cohomology of the Hom complex after injective resolution of the second argument. A key property is that short exact sequences of chain complexes induce long exact sequences in homology: given , there is a long exact sequence where the connecting homomorphisms lift cycles in to boundaries in .

![{\displaystyle \partial _{n}:\,(\sigma :[v_{0},\ldots ,v_{n}]\to X)\mapsto (\sum _{i=0}^{n}(-1)^{i}\sigma :[v_{0},\ldots ,{\hat {v}}_{i},\ldots ,v_{n}]\to X)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d64d20dabc262201e2da3e8e282cd1e6c2a46ce)