Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Event-driven process chain

View on Wikipedia

An event-driven process chain (EPC) is a type of flow chart for business process modeling. EPC can be used to configure enterprise resource planning execution, and for business process improvement. It can be used to control an autonomous workflow instance in work sharing.

The event-driven process chain method was developed within the framework of Architecture of Integrated Information Systems (ARIS) by August-Wilhelm Scheer at the Institut für Wirtschaftsinformatik, Universität des Saarlandes (Institute for Business Information Systems at the University of Saarland) in the early 1990s.[1]

Overview

[edit]Businesses use event-driven process chain diagrams to lay out business process workflows, originally in conjunction with SAP R/3 modeling, but now more widely. It is used by many companies for modeling, analyzing, and redesigning business processes. The event-driven process chain method was developed within the framework of Architecture of Integrated Information Systems (ARIS). As such it forms the core technique for modeling in ARIS, which serves to link the different views in the so-called control view. To quote from a 2006 publication on event-driven process chains:[2]

- An Event-driven process chain (EPC) is an ordered graph of events and functions. It provides various connectors that allow alternative and parallel execution of processes. Furthermore it is specified by the usages of logical operators, such as OR, AND, and XOR. A major strength of EPC is claimed to be its simplicity and easy-to-understand notation. This makes EPC a widely acceptable technique to denote business processes.

The statement that event-driven process chains are ordered graphs is also found in other directed graphs for which no explicit node ordering is provided. No restrictions actually appear to exist on the possible structure of EPCs, but nontrivial structures involving parallelism have ill-defined execution semantics; in this respect they resemble UML activity diagrams.

Several scientific articles are devoted to providing well-defined execution semantics for general event-driven process chains.[3][4] One particular issue is that EPCs require non-local semantics,[5] i.e., the execution behavior of a particular node within an EPC may depend on the state of other parts of the EPC, arbitrarily far away.

Elements

[edit]

These elements are used in event-driven process chain diagrams:

- Event

- Events are passive elements in event-driven process chains. They describe under what circumstances a function or a process works or which state a function or a process results in. Examples of events are "requirement captured", "material in stock", etc. In the EPC graph an event is represented as hexagon. In general, an EPC diagram must start with an event and end with an event.

- Function

- Functions are active elements in an EPC. They model the tasks or activities within the company. Functions describe transformations from an initial state to a resulting state. If different resulting states can occur, the selection of the respective resulting state can be modeled explicitly as a decision function using logical connectors. Functions can be refined into another EPC. In this case it is called a hierarchical function. Examples of functions are "capture requirement", "check material in stock", etc. In the event-driven process chain graph a function is represented as rounded rectangle.

- Process owner

- Process owner is responsible for a function (i.e. a booking clerk is responsible for booking journeys). The process owner is usually part of an organization unit (i.e. a booking clerk belongs to the booking department). It is represented as a square with a vertical line.

- Organization unit

- Organization units determine which organization within the structure of an enterprise is responsible for a specific function. Examples are "sales department", "procurement department", etc. It is represented as an ellipse with a vertical line.

- Information, material, or resource object

- In the event-driven process chain, the information, material, or resource objects portray objects in the real world, for example business objects, entities, etc., which can be input data serving as the basis for a function, or output data produced by a function. Examples are "material", "order", etc. In the EPC graph such an object is represented as rectangle.

- Logical connector

- In the event-driven process chain the logical relationships between elements in the control flow, that is, events and functions are described by logical connectors. With the help of logical connectors it is possible to split the control flow from one flow to two or more flows and to synchronize the control flow from two or more flows to one flow.

- Logical relationships

|

|

- There are three kinds of logical relationships defined in event-driven process chains:

- Branch/Merge: Branch and merge correspond to making decision of which path to choose among several control flows. A branch may have one incoming control flow and two or more outgoing control flows. When the condition is fulfilled, a branch activates exactly only one of the outgoing control flows and deactivates the others. The counterpart of a branch is a merge. A merge may have two or more incoming flows and one outgoing control flow. A merge synchronizes an activated and the deactivated alternatives. The control will then be passed to the next element after the merge. A branch in the EPC is represented by an opening XOR, whereas a merge is represented as a closing XOR connectors.

- Fork/Join : Fork and join correspond to activating all paths in the control flow concurrently. A fork may have one incoming control flow and two or more outgoing control flows. When the condition is fulfilled, a fork activates all of the outgoing control flows in parallel. A join may have two or more incoming control flows and one outgoing control flow. A join synchronizes all activated incoming control flows. In the Event-driven Process Chain diagram how the concurrency achieved is not a matter. In reality the concurrency can be achieved by true parallelism or by virtual concurrency achieved by interleaving. A fork in the EPC is represented by an opening 'AND', whereas a join is represented as a closing 'AND' connectors.

- OR : An 'OR' relationship corresponds to activating one or more paths among control flows. An opening 'OR' connector may have one incoming control flow and two or more outgoing control flows. When the condition is fulfilled, an opening 'OR' connector activates one or more control flows and deactivates the rest of them. The counterpart of this is the closing 'OR' connector. When at least one of the incoming control flows is activated, the closing 'OR' connector will pass the control to the next element after it.

- Control flow

- A control flow connects events with functions, process paths, or logical connectors creating chronological sequence and logical interdependencies between them. A control flow is represented as a dashed arrow.

- Information flow

- Information flows show the connection between functions and input or output data, upon which the function reads changes or writes.

- Organization unit assignment

- Organization unit assignments show the connection between an organization unit and the function it is responsible for.

- Process path

- Process paths serve as navigation aid in the EPC. They show the connection from or to other processes. The process path is represented as a compound symbol composed of a function symbol superimposed upon an event symbol. To employ the process path symbol in an Event-driven Process Chain diagram, a symbol is connected to the process path symbol, indicating that the process diagrammed incorporates the entirety of a second process which, for diagrammatic simplicity, is represented by a single symbol.

Example

[edit]As shown in the example, a customer order received is the initial event which creates a requirement capture within the company. In order to specify this function, sales is responsible for marketing, currency etc. As a result, event 'requirement captured' leads to another new function: check material on stock, in order to manufacture the productions.

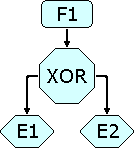

All input or output data about material remains in the information resource. After checking material, two events may happen-with or without material on stock. If positive, get material from stock; if not, order material from suppliers. Since the two situations cannot happen at the same time, XOR is the proper connector to link them together.

Meta-model

[edit]Although a real process may include a series of stages until it is finished eventually, the main activities remain similar. An event triggers one function; and a function will lead to one event. Meanwhile, an event may involve one or more processes to fulfill but a process is unique for one event, the same goes for process and process path.

As for the function, its data may be included in one or more information resources, while organization unit is only responsible for one specific function.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ <trans oldtip="A.-W. Scheer (2002). " newtip="A.-W.Scheer(2002年)。">A.-W.Scheer(2002年)。</trans><trans oldtip="ARIS. Vom Geschäftsprozess zum Anwendungssystem" newtip="阿里斯。vm Gesch ftsprozess zum Anwendungssystem">阿里斯。vm Gesch ftsprozess zum Anwendungssystem</trans>. Springer. p.20.

- ^ <trans oldtip="Anni Tsai et al. (2006). "EPC Workflow Model to WIFA Model Conversion". In: " newtip="Anni Tsai等人(2006年)。“EPC工作流模型到Wifa模型的转换”。在:">Anni Tsai等人(2006年)。“EPC工作流模型到Wifa模型的转换”。在:</trans><trans oldtip="2006 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Taipei, Taiwan" newtip="2006 IEEE系统,人,控制论国际会议,台北,台湾">2006 IEEE系统,人,控制论国际会议,台北,台湾</trans><trans oldtip=", pp. 2758-2763]" newtip=",第2758-2763页]">,第2758-2763页]</trans>

- ^ <trans oldtip="Wil van der Aalst" newtip="Wil van der Aalst">Wil van der Aalst</trans> (1999). <trans oldtip="Formalization and Verification of Event-driven Process Chains" newtip="事件驱动过程链的形式化与验证">事件驱动过程链的形式化与验证</trans> Archived 2006-09-23 at the Wayback Machine<trans oldtip=". In " newtip="。在……里面">。在……里面</trans><trans oldtip="Information & Software Technology 41(10)" newtip="信息和软件技术41(10)">信息和软件技术41(10)</trans><trans oldtip=", pp. 639-650" newtip=",第639-650页">,第639-650页</trans>

- ^ <trans oldtip="Kees van Hee et al. (2006). " newtip="Kees van Hee等人。(2006年)。">Kees van Hee等人。(2006年)。</trans><trans oldtip=""Colored Petri Nets to Verify Extended Event-Driven Process Chains"" newtip="用于验证扩展事件驱动过程链的有色Petri网">用于验证扩展事件驱动过程链的有色Petri网</trans> Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine<trans oldtip=". In " newtip="。在……里面">。在……里面</trans><trans oldtip="Proc. of the 4th Workshop on Modelling, Simulation, Verification and Validation of Enterprise Information Systems (MSVVEIS06)" newtip="第四期企业信息系统建模、仿真、验证和验证讲习班(MSVVEIS 06)">第四期企业信息系统建模、仿真、验证和验证讲习班(MSVVEIS 06)</trans><trans oldtip=", May 23–24, 2006 Paphos, Cyprus, pp. 76-85." newtip=",2006年5月23日至24日,塞浦路斯帕福斯,第76至85页。">,2006年5月23日至24日,塞浦路斯帕福斯,第76至85页。</trans>

- ^ <trans oldtip="Ekkart Kindler (2006). " newtip="Ekkart Kindler(2006年)。">Ekkart Kindler(2006年)。</trans><trans oldtip="On the Semantics of EPCs: A Framework for Resolving the Vicious Circle" newtip="EPC语义学:一个解决恶性循环的框架">EPC语义学:一个解决恶性循环的框架</trans>[permanent dead link]<trans oldtip=". Technical Report. Computer Science Department, University of Paderborn, Germany." newtip="。技术报告。德国帕德尔伯恩大学计算机科学系。">。技术报告。德国帕德尔伯恩大学计算机科学系。</trans>