Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Executable

View on Wikipedia

| Program execution |

|---|

| General concepts |

| Types of code |

| Compilation strategies |

| Notable runtimes |

|

| Notable compilers & toolchains |

|

In computing, an executable is a resource that a computer can use to control its behavior. As with all information in computing, it is data, but distinct from data that does not imply a flow of control.[2] Terms such as executable code, executable file, executable program, and executable image describe forms in which the information is represented and stored. A native executable is machine code and is directly executable at the instruction level of a CPU.[3][4] A script is also executable although indirectly via an interpreter. Intermediate executable code (such as bytecode) may be interpreted or converted to native code at runtime via just-in-time compilation.

Native executable

[edit]Even though it is technically possible to write a native executable directly in machine language, it is generally not done. It is far more convenient to develop software as human readable source code and to automate the generation of machine code via a build toolchain. Today, most source code is a high-level language although it is still possible to use assembly language which is closely associated with machine code instructions. Many toolchains consist of a compiler that generates native code as a set of object files and a linker that generates a native executable from the object and other files. For assembly language, typically the translation tool is called an assembler instead of a compiler.

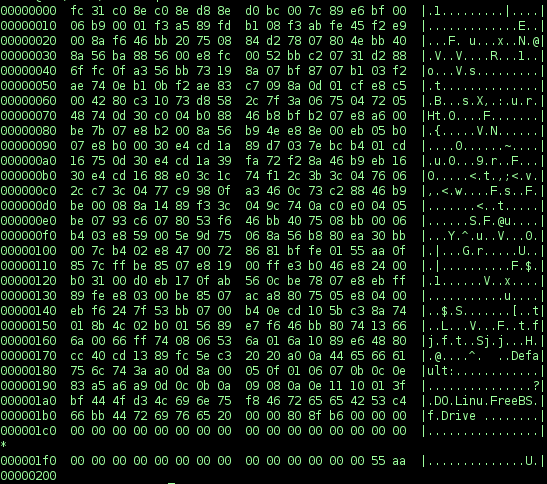

Object files are typically stored in a digital container format that supports structure in the machine code – such as Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) or Portable Executable (PE), depending on the computing context.[5] The format may support segregating code into sections such as .text (executable code), .data (initialized global and static variables), and .rodata (read-only data, such as constants and strings).

Executable files typically include a runtime system, which implements runtime language features (such as task scheduling, exception handling, calling static constructors and destructors, etc.) and interactions with the operating system, notably passing arguments, environment, and returning an exit status, together with other startup and shutdown features such as releasing resources like file handles. For C, this is done by linking in the crt0 object, which contains the actual entry point and does setup and shutdown by calling the runtime library.[6] Executable files thus may contain significant code beyond that directly generated from the source code. In some cases, it is desirable to omit this, for example for embedded systems. In C, this can be done by omitting the usual runtime, and instead explicitly specifying a linker script, which generates the entry point and handles startup and shutdown, such as calling main to start and returning exit status to the kernel at the end.[7]

To be executable, a file must conform to the system's application binary interface (ABI). In simple interfaces, a file is executed by loading it into memory and jumping to the start of the address space and executing from there.[8] In more complicated interfaces, executable files have additional metadata, which may specify relocations to be performed when the program is loaded, or the entry point address at which to start execution.[9]

See also

[edit]- Comparison of executable file formats

- Executable compression – Means of compressing an executable file

- Executable text – Code intended as a payload to exploit a software vulnerability

- Object file – File containing relocatable format machine code

References

[edit]- ^ Celovi, Paul (2002). Embedded FreeBSD Cookbook. Elsevier. pp. 108, 187–188. ISBN 1-5899-5004-6. Retrieved 2022-03-06.

- ^ Mueller, John Paul (2007). Windows Administration at the Command Line for Windows Vista, Windows 2003, Windows XP, and Windows 2000. John Wiley & Sons. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-470-04616-6. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- ^ "executable". Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ^ "Machine Instructions". GeeksforGeeks. 2015-11-03. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ "Chapter 4: Object Files". refspecs.linuxbase.org. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ Fisher, Tim. "List of Executable File Extensions". lifewire.com. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ McKellar, Jessica (2010-03-16). "Hello from a libc-free world! (Part 1)".

- ^ Smith, James E.; Nair, Ravi (2005-05-16). "The Architecture of Virtual Machines". Computer. 38 (5): 33–34. doi:10.1109/MC.2005.173.

- ^ Rusling, David A. (1999). "Chapter 4 – Processes". The Linux Kernel. sec. 4.8.1 – ELF. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

External links

[edit]- EXE File Format at What Is

Executable

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Core Concept

An executable is a file or program segment containing machine code or bytecode that a central processing unit (CPU) or virtual machine can directly execute to perform specified tasks, in contrast to source code which must be processed further or scripts which require an interpreter at runtime.[6][7] This form encodes instructions in a binary format native to the hardware or a managed runtime environment, allowing the computer to carry out operations without additional translation steps during execution.[6] Executables differ from non-executable files, such as source code or data files, by being pre-processed into a ready-to-run state that includes structural elements like headers for metadata, entry points, and dependency information, enabling direct loading into memory for execution.[7] Unlike human-readable source code, which is written in high-level languages and requires compilation or interpretation, or plain-text scripts that are executed line-by-line by an interpreter, executables represent a compiled or assembled output optimized for efficient hardware-level processing.[6] In the software lifecycle, an executable serves as the final output of the build process, transforming developer-written code into a standalone artifact that can be distributed and run independently on compatible systems.[6] This role enables programs to operate without needing the original source or development tools present, facilitating deployment across environments. For example, a basic "Hello World" program assembled from low-level instructions produces a compact binary executable that outputs the message upon running, whereas an equivalent Python script remains as interpreted text requiring a runtime environment like the Python interpreter to execute.[8][6]Key Characteristics

Executables feature a modular internal structure designed to facilitate loading and execution by the operating system. At the core is a header that provides essential metadata, including a magic number to identify the file format—such as 0x7F 'E' 'L' 'F' for ELF files or the "PE\0\0" signature for Portable Executable (PE) files—along with details on the file's architecture, entry point, and layout of subsequent sections.[9][1] Following the header, the file is divided into sections, each serving a distinct purpose: the .text section contains the machine code instructions, marked as read-only to prevent modification; the .data section holds initialized global and static variables; the .bss section reserves space for uninitialized variables, which are zeroed at runtime; and a symbol table section stores references to functions and variables for linking and debugging.[9][1] This segmented organization allows tools like linkers and loaders to efficiently parse and map the file into memory.[10] Portability of executables is inherently limited by dependencies on the target CPU architecture and operating system. For instance, binaries compiled for x86 architectures use a different instruction set than those for ARM, rendering them incompatible without recompilation or emulation.[11] Additionally, operating system variations introduce challenges such as endianness—where x86 systems typically employ little-endian byte ordering while some others use big-endian—and differing calling conventions that dictate how function parameters are passed between caller and callee.[12] These factors necessitate architecture-specific and OS-specific builds to ensure correct execution, as mismatches can lead to crashes or undefined behavior.[13] Key attributes of executables include memory protection mechanisms that enhance security and stability during runtime. The code segment (.text) is configured with read-only and executable permissions, preventing accidental or malicious writes to instructions while allowing the CPU to fetch and execute them.[14] In contrast, data segments (.data and .bss) are granted read-write permissions for variable modifications but are non-executable to mitigate code injection risks.[14] Runtime memory is further segregated into stack and heap regions: the stack, used for local variables and function calls, operates on a last-in-first-out basis with automatic allocation and deallocation; the heap, for dynamic allocations via functions like malloc, grows as needed and requires explicit management to avoid leaks or overflows.[15] This separation ensures efficient resource use and isolation of execution contexts.[16] The size of an executable binary is influenced by optimization techniques applied during compilation and linking, which balance performance, functionality, and efficiency. Dead code elimination, a common optimization, removes unused functions, variables, and instructions that are never reached, directly reducing the final file size and improving load times— for example, interprocedural analysis can significantly reduce code size in large programs by identifying unreferenced sections.[17] Other factors include the inclusion of debug symbols (which can be stripped post-build), alignment padding for hardware requirements, and the embedding of runtime libraries, all of which contribute to variability in binary footprint across builds.[18] These optimizations prioritize minimalism without sacrificing correctness, making executables more suitable for distribution and deployment.[17]Creation Process

Compilation and Linking

The compilation phase of creating an executable begins with translating high-level source code, such as C or C++, into machine-readable object files using a compiler like the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC).[19] This process involves multiple sub-phases in the compiler's frontend: lexical analysis, where the source code is scanned to identify tokens such as keywords, identifiers, and operators while ignoring whitespace and comments; syntax analysis or parsing, which checks the token sequence against the language's grammar to build a parse tree representing the program's structure; and semantic analysis, which verifies type compatibility, scope rules, and other meaning-related aspects to ensure the code is valid beyond syntax.[20] Following these, the compiler generates intermediate code, applies optimizations to improve efficiency (such as dead code elimination or loop unrolling), and produces target-specific assembly code through the backend's code generation phase.[21] The assembly step converts the generated assembly code into relocatable object files, typically using the GNU Assembler (as), which translates low-level instructions into binary object code while preserving relocation information for unresolved addresses and symbols.[22] These object files contain the program's machine code segments, data, and symbol tables but are not yet executable, as external references (like function calls to libraries) remain unresolved.[22] In the linking phase, a linker such as GNU ld combines multiple object files and libraries into a single executable image by resolving symbols—mapping references to their definitions—and assigning final memory addresses. Static linking embeds the entire contents of required libraries directly into the executable, resulting in a self-contained file that includes all necessary code at build time, which increases file size but eliminates runtime dependencies.[23] In contrast, dynamic linking incorporates only stubs or references to external libraries, deferring full resolution to runtime via a dynamic linker, which allows shared libraries to be loaded once and reused across programs but requires the libraries to be present on the target system.[23] The linker also handles relocation, adjusting addresses in the object code to fit the final layout, and produces formats like ELF for Unix-like systems.Source to Executable Conversion

The transformation from high-level source code, such as C or C++ files, to a runnable executable follows a structured pipeline that ensures the code is processed into machine-readable instructions compatible with the target system. This end-to-end workflow begins with preprocessing and progresses through compilation, assembly, and linking, automating the conversion while resolving dependencies and optimizing for execution.[19] Preprocessing is the initial stage, where the compiler's preprocessor expands macros, resolves include directives to incorporate header files, and handles conditional compilation based on directives like#ifdef. This step modifies the source code to produce an intermediate form ready for further processing, often expanding files like .c or .cpp without altering the core logic.[19] The output is then fed into compilation, where the compiler translates the preprocessed code into assembly language, generating human-readable instructions specific to the target architecture. Assembly follows immediately, converting this assembly code into object files (typically .o or .obj) that contain relocatable machine code segments.[19] Finally, linking combines these object files with required libraries, resolving external references to form a cohesive executable file, such as a.out on Unix-like systems or an .exe on Windows.[19]

To automate and scale this pipeline across complex projects involving multiple source files, build systems play a crucial role in managing dependencies, incremental builds, and platform variations. Makefiles, part of the GNU Make tool, define rules specifying targets (e.g., the executable), prerequisites (e.g., object files), and shell commands (recipes) to execute the stages, using file timestamps to recompile only modified components.[24] CMake, a cross-platform meta-build system, generates native build files (e.g., Makefiles or Visual Studio projects) from a high-level CMakeLists.txt script, using commands like add_executable() to define the output and target_link_libraries() to handle linking dependencies.[25] Integrated development environments (IDEs), such as Visual Studio or Eclipse, often integrate these tools or provide built-in builders to streamline the workflow within a graphical interface.[25]

Cross-compilation extends this pipeline to produce executables for architectures different from the host machine, enabling development on powerful desktops for embedded or remote targets. For instance, using GCC, developers specify the target triple (e.g., arm-linux-gnueabi-gcc) to configure the toolchain, ensuring preprocessing, compilation, and assembly generate code for the desired platform, such as building Windows executables on a Linux host.[26] This requires matching libraries and headers for the target, often managed by build systems like CMake through toolchain files that override default settings.[26]

Throughout the conversion, error handling is essential to identify issues early and maintain code integrity. During compilation, type mismatches—such as incompatible pointer assignments or implicit conversions that alter values—trigger warnings or errors, configurable via flags like -Wconversion or -Wincompatible-pointer-types to enforce strict type checking.[27] In the linking phase, unresolved symbols occur when references to functions or variables lack corresponding definitions in the object files or libraries, leading to linker errors that halt the build unless suppressed with options like --unresolved-symbols=ignore-all.[28] These issues, often stemming from missing includes, incorrect library paths, or mismatched declarations across files, demand iterative debugging to ensure a successful executable output.[28]

Types and Formats

Native vs. Managed Executables

Native executables are programs compiled directly into machine code tailored to a specific CPU architecture, allowing the operating system to execute them without additional interpretation or translation layers.[29] This direct compilation, often from languages like C or C++, results in binaries such as ELF files on Linux or PE files on Windows, with no runtime overhead during execution beyond the OS loader.[30] In contrast, they require recompilation for different platforms, limiting portability, and place the burden of memory management and error handling on the developer, which can lead to issues like buffer overflows if not implemented carefully.[31] Managed executables, on the other hand, are compiled into an intermediate representation, such as Common Intermediate Language (CIL) in .NET or bytecode in Java, which is not directly executable by the hardware.[29] These executables rely on a virtual machine— like the Common Language Runtime (CLR) for .NET or the Java Virtual Machine (JVM)—to perform just-in-time (JIT) compilation at runtime, converting the intermediate code to native machine instructions as needed.[32] Examples include .NET assemblies (.dll or .exe files containing CIL, structured in the PE format on Windows) and Java class files (.class files containing bytecode, typically packaged in JAR archives based on the ZIP format).[30][33] The primary advantages of native executables lie in their performance and efficiency: they execute at full hardware speed with minimal startup latency and no ongoing runtime costs, making them ideal for resource-constrained or high-performance applications like system software.[31] However, their platform specificity reduces cross-architecture portability, requiring separate builds for each target environment, such as x86 versus ARM. Managed executables offer enhanced portability, as the same intermediate code can run on any platform with the appropriate virtual machine, facilitating "write once, run anywhere" development.[32] They also provide built-in security features, such as automatic memory management via garbage collection and type safety enforced by the runtime, reducing common vulnerabilities like memory leaks.[29] Drawbacks include dependency on the runtime environment, which adds installation requirements and potential performance overhead from JIT compilation, though optimizations mitigate this in modern implementations.[34] Hybrid approaches bridge these paradigms by applying ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation to managed code, producing native executables from intermediate representations without JIT at runtime. In .NET, Native AOT compiles CIL directly to machine code during the build process, yielding self-contained binaries with faster startup times and smaller memory footprints compared to traditional JIT-managed executables, while retaining managed benefits like garbage collection.[34] This method enhances deployment scenarios, such as cloud-native applications or mobile apps, by reducing runtime dependencies, though it may limit dynamic features like reflection.[35]Common File Formats

Executable file formats standardize the structure of binaries across operating systems, enabling loaders to map code, data, and metadata into memory for execution. Major formats include the Portable Executable (PE) for Windows, the Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) for Unix-like systems, and Mach-O for Apple platforms, each defining headers, sections, and linking information tailored to their ecosystems. Additional formats like the legacy Common Object File Format (COFF) and the WebAssembly binary format (WASM) address specialized or emerging use cases, such as object files and web-native execution.[1][9][3] The Portable Executable (PE) format serves as the standard for executable files on Microsoft Windows and Win32/Win64 systems, encompassing applications (.exe files) and dynamic-link libraries (.dll files). It begins with a DOS header for compatibility with MS-DOS, followed by a PE signature, COFF file header, optional header with subsystem information and data directories (such as imports and exports), and an array of section headers that define the layout of segments like .text for executable code, .data for initialized data, .rdata for read-only data, and .bss for uninitialized data. This structure allows the Windows loader to relocate the image, resolve imports, and initialize the process environment, supporting features like address space layout randomization (ASLR) for security. PE files are extensible, accommodating debug information, resources, and certificates in dedicated sections.[1] The Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) is the predominant format for executables, object files, shared libraries, and core dumps on Unix-like operating systems, including Linux and Solaris. Defined by the Tool Interface Standard, an ELF file starts with an ELF header specifying the file class (32-bit or 64-bit), endianness, ABI version, and entry point, followed by optional program header tables that describe loadable segments (e.g., PT_LOAD for code and data) and section header tables that organize content into sections like .text for code, .data for initialized variables, .rodata for constants, and .symtab for symbols. Program headers guide the dynamic loader in mapping segments into virtual memory, while sections facilitate linking and debugging; shared objects (.so files) use ELF to enable dynamic linking at runtime. ELF's flexibility supports multiple architectures and processor-specific features, such as note sections for auxiliary information.[9] Mach-O, short for Mach Object, is the executable format used in macOS, iOS, watchOS, and tvOS, organizing binaries into a header, load commands, and segments containing sections for efficient loading by the dyld dynamic linker. The header identifies the CPU type, file type (e.g., MH_EXECUTE for executables or MH_DYLIB for libraries), and number of load commands, which specify details like segment permissions, symbol tables, and dynamic library paths. Segments such as __TEXT (for code and read-only data) and __DATA (for writable data) group related sections, with __LINKEDIT holding linking information; Mach-O supports "fat" binaries that embed multiple architectures (e.g., x86_64 and arm64) in one file, allowing universal execution across devices like Intel-based Macs and Apple Silicon. This format integrates with Apple's code-signing system, embedding entitlements and signatures directly in the binary.[3] Other notable formats include the Common Object File Format (COFF), a legacy predecessor to PE used primarily for object files (.obj) in Windows toolchains and older Unix systems, featuring a file header with machine type and section count, followed by optional headers, section tables, and raw section data for relocatable code and symbols. COFF lacks the full executable portability of PE but remains relevant in build processes for its simplicity in handling intermediate compilation outputs. In contrast, WebAssembly (WASM) provides a platform-independent binary format for high-performance execution in web browsers and standalone runtimes, encoding modules as a sequence of typed instructions in a compact, linear bytecode structure with sections for code, data, types, functions, and imports/exports, compiled from languages like C++ or Rust to run sandboxed at near-native speeds without traditional OS dependencies.[1][36]Execution Mechanism

Loading and Running

The loading of an executable into memory begins when the operating system kernel receives a request to execute a program file, typically through system calls that initiate process creation. The kernel first reads the executable's header to verify its format and extract metadata about memory layout, such as segment sizes and permissions. For instance, in Linux systems using the ELF format, the kernel'sload_elf_binary() function parses the ELF header and program header table to identify loadable segments like code, data, and BSS.[37] Similarly, in Windows with the PE format, the loader examines the DOS header, NT headers, and optional header to determine the image base and section alignments.[1]

Once headers are parsed, the kernel maps the executable's segments into the process's virtual address space, allocating memory pages as needed without immediately loading all physical pages to support demand paging. Read-only segments like code are mapped with execute permissions, while data segments receive read-write access; the BSS segment, representing uninitialized data, is zero-filled by allocating fresh pages. The kernel also establishes the stack and heap regions: the stack grows downward from a high virtual address, often with address space layout randomization (ASLR) for security, while the heap starts just after the data segment and expands via system calls like brk() or mmap(). In Linux, setup_arg_pages() configures the initial stack size and adjusts memory accounting for argument pages.[37] Windows performs analogous mappings through the Ntdll.dll loader, reserving virtual memory for sections and committing pages on demand.[1]

Process creation integrates loading in operating system-specific models. In Unix-like systems such as Linux, the common approach uses the fork-exec paradigm: the fork() system call duplicates the parent process to create a child, sharing the address space initially via copy-on-write, after which the child invokes execve() to replace its image with the new executable.[38][39] The execve() call triggers the kernel to load the binary, clear the old address space via flush_old_exec(), and set up the new one, returning control to the child only on success. In contrast, Windows employs the CreateProcess() API, which atomically creates a new process object, allocates its virtual address space, loads the specified executable, and starts its primary thread in a single operation, inheriting the parent's environment unless overridden.[40]

After loading, execution begins at the designated entry point, with the kernel performing final initializations. In Linux ELF executables, the kernel jumps to the entry address from the ELF header (or the dynamic linker's if present) via start_thread(), having populated the stack with the argument count argc, an array of argument pointers argv (with argv[0] typically the program name), environment pointers envp, and an auxiliary vector containing metadata like the entry point and page size.[37][39] The actual entry symbol _start, provided by the C runtime (e.g., in glibc's crt1.o), receives these via the stack or registers, initializes the runtime environment (such as constructors and global variables), and invokes __libc_start_main() to call the user's main(int argc, char *argv[]) function.[41] For Windows PE executables, the loader computes the entry point by adding the AddressOfEntryPoint RVA from the optional header to the image base, then starts the primary thread there; the C runtime entry (e.g., mainCRTStartup) similarly sets up argc and argv from the command line before calling main.[1]

Process termination occurs when the program calls an exit function, such as exit() in C, which sets an exit code and triggers cleanup. The exit code, an integer typically 0 for success and non-zero for failure, is returned to the parent process; in Linux, the least significant byte of the status is passed via wait() or waitpid(), while the kernel reaps the process, freeing its memory mappings, closing file descriptors, and releasing other resources to prevent leaks.[42] If the parent ignores SIGCHLD or has set SA_NOCLDWAIT, the child is immediately reaped without becoming a zombie. In Windows, ExitProcess() sets the exit code (queryable via GetExitCodeProcess()) and notifies loaded DLLs, terminates all threads, unmaps the image from memory, and closes kernel handles, though persistent objects like files may remain if referenced elsewhere.[43] Forced termination via signals (e.g., SIGKILL in Unix) or TerminateProcess() in Windows bypasses runtime cleanup but still reclaims system resources.

Dynamic Linking and Libraries

Dynamic linking allows executables to reference external shared libraries at runtime rather than embedding all code during compilation, enabling modular program design where libraries like.dll files on Windows or .so files on Unix-like systems are loaded on demand. This process relies on symbol tables within the executable and library files, which contain unresolved references to functions and variables; the runtime system resolves these symbols by searching for matching exports in loaded libraries, often using a dynamic symbol table for efficient lookups. Lazy loading defers the actual loading of a library until the first reference to one of its symbols is encountered, optimizing memory usage by avoiding unnecessary loads for unused components.

The runtime loader, such as dyld on macOS or ld.so on Linux, manages this linking process by handling symbol resolution, applying relocations to adjust addresses based on the library's load position, and enforcing versioning to ensure compatibility between executable and library versions. For instance, ld.so on Linux uses a dependency tree to load prerequisite libraries recursively and performs global symbol resolution to bind imports across modules. Versioning mechanisms, like sonames in ELF files, prevent conflicts by specifying minimum required library versions, allowing multiple variants to coexist on the system.

One key advantage of dynamic linking is the reduction in executable file size, as shared code is stored once in libraries and reused across multiple programs, which also facilitates easier updates to libraries without recompiling dependent executables. However, it introduces challenges such as dependency conflicts, colloquially known as "DLL hell" on Windows, where mismatched library versions can cause runtime failures if the system loads an incompatible variant.

To support dynamic linking effectively, executables and shared libraries often employ position-independent code (PIC), which compiles instructions to be relocatable without fixed addresses, using techniques like relative addressing and GOT/PLT tables to defer address resolution until runtime. This enables libraries to be loaded at arbitrary memory locations and shared among processes, enhancing system efficiency, though it may incur a slight performance overhead due to indirect jumps. In contrast to static linking, where all library code is incorporated at build time, dynamic linking promotes resource sharing but requires careful management of dependencies.

Security Considerations

Vulnerabilities and Protections

Executables are susceptible to buffer overflow vulnerabilities, where programs write more data to a fixed-length buffer than it can hold, potentially overwriting adjacent memory regions such as return addresses on the stack.[44] This occurs due to the intermixing of data storage areas and control data in memory, allowing malformed inputs to alter program control flow and enable arbitrary code execution.[44] Stack smashing attacks exemplify this risk, exploiting stack-based buffer overflows in C programs by using functions likestrcpy() to copy excessive data, overwriting the return address to redirect execution to injected shellcode.[45]

Code injection vulnerabilities further compound these threats, arising when executables fail to neutralize special elements in externally influenced inputs, permitting attackers to insert and execute malicious code.[46] For instance, unvalidated user inputs can be interpreted as executable commands in languages like PHP or Python, leading to unauthorized actions such as system calls.[46]

To mitigate these exploits, operating systems implement protections like Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), which randomly relocates key areas of a process's virtual address space—including stacks, heaps, and loaded modules—at runtime to thwart address prediction by attackers.[47] Complementing ASLR, Data Execution Prevention (DEP) uses the processor's NX (No eXecute) bit to mark certain memory pages as non-executable, preventing buffer overflow payloads from running code in data regions like the stack or heap.[48] If execution is attempted on non-executable memory, DEP triggers an access violation, terminating the process to block exploitation.[48]

Executables also serve as primary vectors for malware, including viruses that attach to legitimate files and activate upon execution, spreading via shared disks or networks.[49] Trojans similarly masquerade as benign executables, such as email attachments or downloads, tricking users into running them to grant attackers backdoor access or data exfiltration capabilities.[50] Malware detection often relies on heuristic methods, which analyze runtime behaviors in simulated environments to identify suspicious actions like self-replication, even for unknown variants without matching signatures.[51]

Best practices for securing executables emphasize input validation, where data is checked early against allowlists for format, length, and semantics to block malformed inputs that could trigger overflows or injections.[52] Additionally, least privilege execution restricts processes to minimal necessary permissions, confining potential damage from compromised executables by elevating privileges only when required and dropping them immediately afterward.[53]