Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Five lemma

View on WikipediaIn mathematics, especially homological algebra and other applications of abelian category theory, the five lemma is an important and widely used lemma about commutative diagrams. The five lemma is not only valid for abelian categories but also works in the category of groups, for example.

The five lemma can be thought of as a combination of two other theorems, the four lemmas, which are dual to each other.

Statements

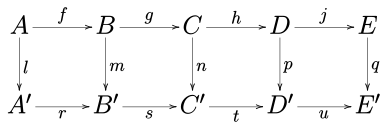

[edit]Consider the following commutative diagram in any abelian category (such as the category of abelian groups or the category of vector spaces over a given field) or in the category of groups.

The five lemma states that, if the rows are exact, m and p are isomorphisms, l is an epimorphism, and q is a monomorphism, then n is also an isomorphism.

The two four-lemmas state:

Proof

[edit]The method of proof we shall use is commonly referred to as diagram chasing.[1] We shall prove the five lemma by individually proving each of the two four lemmas.

To perform diagram chasing, we assume that we are in a category of modules over some ring, so that we may speak of elements of the objects in the diagram and think of the morphisms of the diagram as functions (in fact, homomorphisms) acting on those elements. Then a morphism is a monomorphism if and only if it is injective, and it is an epimorphism if and only if it is surjective. Similarly, to deal with exactness, we can think of kernels and images in a function-theoretic sense. The proof will still apply to any (small) abelian category because of Mitchell's embedding theorem, which states that any small abelian category can be represented as a category of modules over some ring. For the category of groups, just turn all additive notation below into multiplicative notation, and note that commutativity of abelian group is never used.

So, to prove (1), assume that m and p are surjective and q is injective.

- Let c′ be an element of C′.

- Since p is surjective, there exists an element d in D with p(d) = t(c′).

- By commutativity of the diagram, u(p(d)) = q(j(d)).

- Since im t = ker u by exactness, 0 = u(t(c′)) = u(p(d)) = q(j(d)).

- Since q is injective, j(d) = 0, so d is in ker j = im h.

- Therefore, there exists c in C with h(c) = d.

- Then t(n(c)) = p(h(c)) = t(c′). Since t is a homomorphism, it follows that t(c′ − n(c)) = 0.

- By exactness, c′ − n(c) is in the image of s, so there exists b′ in B′ with s(b′) = c′ − n(c).

- Since m is surjective, we can find b in B such that b′ = m(b).

- By commutativity, n(g(b)) = s(m(b)) = c′ − n(c).

- Since n is a homomorphism, n(g(b) + c) = n(g(b)) + n(c) = c′ − n(c) + n(c) = c′.

- Therefore, n is surjective.

Then, to prove (2), assume that m and p are injective and l is surjective.

- Let c in C be such that n(c) = 0.

- t(n(c)) is then 0.

- By commutativity, p(h(c)) = 0.

- Since p is injective, h(c) = 0.

- By exactness, there is an element b of B such that g(b) = c.

- By commutativity, s(m(b)) = n(g(b)) = n(c) = 0.

- By exactness, there is then an element a′ of A′ such that r(a′) = m(b).

- Since l is surjective, there is a in A such that l(a) = a′.

- By commutativity, m(f(a)) = r(l(a)) = m(b).

- Since m is injective, f(a) = b.

- So c = g(f(a)).

- Since the composition of g and f is trivial, c = 0.

- Therefore, n is injective.

Combining the two four lemmas now proves the entire five lemma.

Applications

[edit]The five lemma is often applied to long exact sequences: when computing homology or cohomology of a given object, one typically employs a simpler subobject whose homology/cohomology is known, and arrives at a long exact sequence which involves the unknown homology groups of the original object. This alone is often not sufficient to determine the unknown homology groups, but if one can compare the original object and sub object to well-understood ones via morphisms, then a morphism between the respective long exact sequences is induced, and the five lemma can then be used to determine the unknown homology groups.

In particular it is quite helpful in proving two (co)homology theories of the same object coincide, e.g. simplicial versus singular homology, de Rham cohomology versus singular cohomology.

See also

[edit]- Short five lemma, a special case of the five lemma for short exact sequences

- Snake lemma, another lemma proved by diagram chasing

- Nine lemma

Notes

[edit]- ^ Massey (1991). A basic course in algebraic topology. p. 184.

References

[edit]- Scott, W.R. (1987) [1964]. Group Theory. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-65377-8.

- Massey, William S. (1991), A basic course in algebraic topology, Graduate texts in mathematics, vol. 127 (3rd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-97430-9